Targeted vs. Untargeted Lipidomics in Diabetes Research: Strategies for Biomarker Discovery and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of targeted and untargeted lipidomics and their transformative role in diabetes research.

Targeted vs. Untargeted Lipidomics in Diabetes Research: Strategies for Biomarker Discovery and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of targeted and untargeted lipidomics and their transformative role in diabetes research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of each approach, detailing their specific applications in discovering novel lipid biomarkers and elucidating dysregulated pathways in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), such as sphingolipid and glycerophospholipid metabolism. It delivers a practical comparison of methodological workflows, from sample preparation to data analysis, and addresses key challenges including standardization, quantification, and data complexity. Furthermore, the article examines validation strategies and the emerging paradigm of integrating both approaches to accelerate the translation of lipidomic findings into personalized diagnostic and therapeutic solutions for diabetes and its complications.

Lipidomics in Diabetes: Unveiling the Lipid Landscape from Discovery to Hypothesis

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, has become an indispensable tool for understanding the molecular mechanisms of complex metabolic diseases like Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) [1]. Based on methodological frameworks and research objectives, this field bifurcates into two distinct yet complementary paradigms: untargeted lipidomics (hypothesis-generating) and targeted lipidomics (hypothesis-driven) [1]. These approaches differ fundamentally in their conceptual frameworks, analytical objectives, and technological requirements, while sharing foundational principles in lipid characterization. Within diabetes research, both strategies have revealed that dysregulation of lipid metabolism—including disruptions in sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, and sterol ester pathways—plays a central role in disease pathogenesis and progression [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these core approaches, enabling researchers to select context-appropriate strategies for advancing diabetes investigation.

Conceptual Frameworks and Technical Specifications

Untargeted Lipidomics: A Comprehensive Discovery Platform

Untargeted lipidomics employs a holistic analytical strategy to profile the complete lipid repertoire within biological specimens without prior selection of targets [1]. This hypothesis-free approach serves as a powerful discovery tool to map lipid diversity, uncover novel metabolic pathways, and elucidate lipid functional networks across biological systems [1]. In practice, untargeted approaches have identified significant alterations in 44 lipid metabolites in newly diagnosed T2DM patients and 29 in high-risk individuals compared with healthy controls [2].

Technical Foundation: Untargeted lipidomics relies on high-resolution mass spectrometers (HRMS) such as Q-TOF or Orbitrap instruments, which achieve resolutions exceeding 120,000 FWHM with sub-1 ppm mass accuracy [1]. This enables differentiation of near-isobaric species and detection of both known and uncharacterized lipid species across all major classes. Data acquisition typically involves full-spectrum scanning (m/z 50–2000) complemented by data-dependent acquisition (DDA) to enhance structural elucidation through fragmentation of the most abundant ions [1].

Targeted Lipidomics: A Precision-Focused Approach

Targeted lipidomics adopts a hypothesis-driven methodology, focusing on precise quantification of predefined lipid panels [1]. Leveraging techniques such as Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), this approach prioritizes analytical rigor for specific lipid classes or molecules known to be biologically relevant to diabetes pathology. Targeted methods have proven invaluable for validating candidate biomarkers initially discovered through untargeted screening, such as specific sphingolipids associated with insulin resistance [3].

Technical Foundation: Targeted approaches typically employ triple quadrupole (QQQ) mass spectrometers operated in Selective Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM) or Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) modes [1]. These platforms monitor specific precursor-to-product ion transitions (e.g., m/z 780→184 for PC 16:0/18:1) to isolate target signals while effectively filtering background noise. The use of isotopically labeled internal standards enables absolute quantification with sub-nanomolar sensitivity, which is particularly valuable for low-abundance lipid signaling mediators like ceramides or eicosanoids [1].

Table 1: Core Conceptual and Technical Comparison

| Dimension | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Framework | Hypothesis-generating, global analysis | Hypothesis-driven, focused analysis |

| Analytical Scope | Comprehensive profiling of known and unknown lipids | Precise quantification of predefined lipid panels |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative (relative quantification) | Absolute quantification (standard curve method) |

| Instrument Configuration | Q-TOF, Orbitrap (high resolution) | Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) |

| Data Complexity | High, requires sophisticated bioinformatics | Lower, streamlined analysis |

| Ideal Application | Biomarker discovery, novel pathway identification | Biomarker validation, clinical diagnostics, therapeutic monitoring |

Experimental Protocols in Diabetes Research

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Lipid Extraction Protocol (Common to Both Approaches): Serum samples are typically prepared using liquid-liquid extraction methods. In a representative diabetes study [2]:

- 30 μL of serum is mixed with 200 μL of methanol containing 1 μg/mL of internal standards

- 660 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether and 150 μL of water are added, followed by vortexing for 5 minutes

- After centrifugation, 600 μL of the upper organic phase is concentrated to dryness in a vacuum centrifuge

- The residue is reconstituted in 600 μL of acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (65:30:5, v/v/v) mixture

- After centrifugation, 10 μL of supernatant is injected into the LC-MS/MS system

Key Variations: While targeted approaches often incorporate class-specific internal standards for precise quantification, untargeted methods may use fewer internal standards for general quality control [1].

Chromatographic Separation Conditions

Untargeted Protocol: A representative untargeted lipidomics analysis in diabetes research employed [4]:

- Column: Acquity Ultra Performance LC C18-RP (ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 1.7μM, Waters)

- Mobile Phase A: acetonitrile/water (60:40) with 10mM ammonium formate

- Mobile Phase B: isopropanol/acetonitrile (90:10) with 10mM ammonium formate

- Gradient: 0–2 min, 15–30% B; 2–2.5 min, 48% B; 2.5–11 min, 82% B; 11–11.5 min, 99% B; 11.5–12 min, 99% B; 12–12.1 min, 15% B; 12.1–15 min, 15% B

Targeted Protocol: A targeted lipidomics study for diabetic retinopathy utilized [5]:

- Column: Kinetex C18 (2.6 μm 2.1 × 100 mm)

- Mobile Phase A: water with 10mM ammonium acetate

- Mobile Phase B: acetonitrile-isopropanol (90:10) with 10mM ammonium acetate

- Gradient: Linear elution over 17 minutes with increasing organic phase

Mass Spectrometry Parameters

Table 2: Typical MS Instrument Conditions

| Parameter | Untargeted Approach | Targeted Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument Type | Q Exactive Orbitrap (Thermo Scientific) | Triple Quadrupole 6500+ (AB SCIEX) |

| Ionization Mode | ESI positive/negative | ESI positive/negative |

| Spray Voltage | 3.5 kV (positive), -3.5 kV (negative) | 5.5 kV (positive), -4.5 kV (negative) |

| Scan Range | m/z 10–1200 | Specific MRM transitions |

| Capillary Temperature | 450°C | 350°C |

| Collision Energy | Stepped (20, 35, 50 eV) | Optimized per transition |

Integrated Workflow and Strategic Application

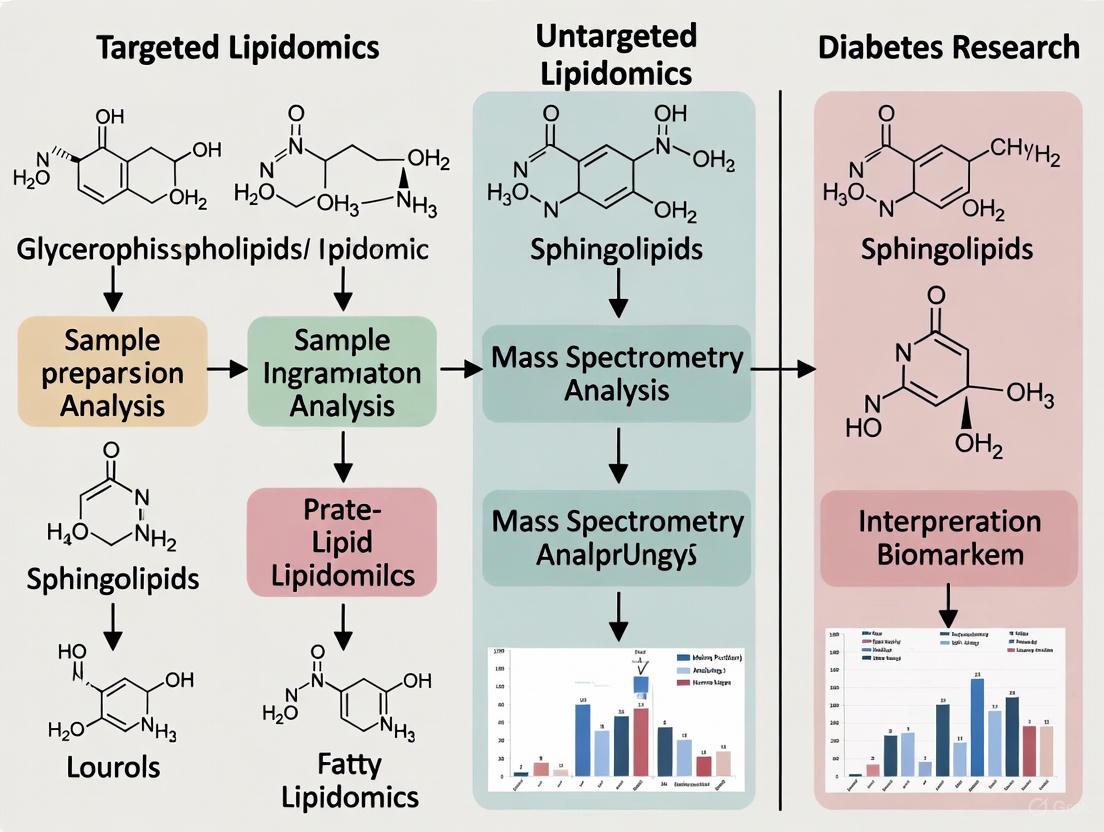

The synergy between untargeted and targeted approaches creates a powerful framework for advancing diabetes research. The complementary relationship between these methodologies can be visualized as an integrated workflow:

This integrated approach has successfully identified clinically relevant lipid signatures in diabetes. For instance, one study combining both methods identified four specific lipid species (PC(18:022:4), LPC(14:0), PE(16:118:2), and PE(18:0_22:4)) as potential biomarkers in T2DM, all of which were downregulated in diabetic subjects [6]. Similarly, another integrated analysis revealed disruptions in key metabolic pathways including sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, and sterol ester metabolism in T2DM progression [2].

Diabetes-Specific Lipid Alterations and Pathway Implications

Lipidomics studies have revealed consistent alterations in specific lipid classes across multiple diabetes investigations:

Table 3: Key Lipid Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

| Lipid Class | Direction of Change | Potential Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sphingomyelins | Both increased & decreased species | Insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction |

| Phosphatidylcholines | Multiple species decreased | Membrane integrity, inflammation modulation |

| Triacylglycerols | Generally increased | Energy metabolism dysregulation |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines | Multiple species decreased | Mitochondrial function, membrane fluidity |

| Ceramides | Specific species increased | Insulin resistance, apoptosis signaling |

Pathway enrichment analyses consistently identify several metabolic pathways as significantly disrupted in diabetes, including glycerophospholipid metabolism, sphingolipid metabolism, and glycerolipid metabolism [7] [6]. These pathways represent potential therapeutic targets and mechanistic insights into diabetes pathology.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of lipidomics workflows requires specific high-quality reagents and materials:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation, sample reconstitution | Low UV absorbance, high purity (MeOH, ACN, IPA, MTBE) |

| Ammonium Formate/Acetate | Mobile phase additive | Enhances ionization, improves chromatographic separation |

| Internal Standards | Quantification normalization | Isotope-labeled (¹³C, ²H) lipid analogs for each class |

| C18/C8 RP Columns | Lipid separation | 100-150mm length, 1.7-2.6μm particle size, 2.1mm i.d. |

| Quality Control Pool | System performance monitoring | Pooled representative samples for sequence monitoring |

Untargeted and targeted lipidomics represent complementary paradigms that together provide a comprehensive approach to understanding lipid dysregulation in diabetes. The hypothesis-generating power of untargeted methods enables discovery of novel lipid biomarkers and pathways, while the precision of targeted approaches allows rigorous validation and absolute quantification of clinically relevant lipid species. The integrated application of both strategies, as demonstrated across multiple diabetes studies, offers the most powerful framework for advancing our understanding of diabetes pathogenesis, identifying diagnostic biomarkers, and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. As lipidomics technologies continue to evolve, these approaches will undoubtedly yield further insights into the complex metabolic disruptions underlying diabetes and its complications.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from impaired insulin secretion and/or insulin resistance, accounting for over 96% of all diabetes cases globally [8]. The pathogenesis of T2DM involves a multifactorial interplay of genetic and environmental factors, with dysregulated lipid metabolism now recognized as a central contributor to disease development and progression [9] [2] [8]. Lipidomics—the global assessment of lipids using mass spectrometry—has emerged as a powerful approach for uncovering the dynamic alterations in lipid species across different stages of T2DM [2] [10]. These comprehensive profiling strategies have revealed that disruptions in lipid homeostasis often precede detectable functional decline, highlighting their potential value for early diagnosis and intervention [9]. This review examines how targeted and untargeted lipidomics approaches are advancing our understanding of T2DM pathogenesis, comparing their technical capabilities, applications, and contributions to identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Lipidomics Approaches: Technical Comparison

Mass spectrometry-based lipidomics can be performed using either untargeted or targeted approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations [10]. Untargeted lipidomics provides a broad, unbiased assessment of lipid species present in a sample, typically using high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to detect a wide range of molecular ions without prior selection [2] [10]. This approach is particularly valuable for hypothesis generation and discovering novel lipid alterations associated with disease states. In contrast, targeted lipidomics focuses on precise quantification of predefined lipid classes using techniques like multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), often with differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) separation, enabling high-throughput, accurate measurement of specific lipid panels with enhanced sensitivity and reproducibility [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Platforms

| Feature | Untargeted LC-MS Approach | Targeted Lipidyzer Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition | Reverse phase LC separation with high-resolution MS detection | DMS separation with MRM detection |

| Lipid Coverage | Broad, unbiased detection; 337 lipids across 11 classes in mouse plasma | Predefined lipid panels; 342 lipids across similar classes |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative (relative abundance) | Absolute quantification using deuterated internal standards |

| Triacylglycerol Identification | Identifies all three fatty acids in TAG species | Reports one fatty acid with total carbons/unsaturation |

| Technical Repeatability | Median CV 6.9% | Median CV 4.7% |

| Throughput | Slower data processing requiring manual validation | Fast, automated data processing |

| Unique Strengths | Detection of novel lipids, ether-linked PCs, PIs | Excellent for FFA, CE, high-throughput applications |

A cross-platform comparison of these approaches revealed complementary capabilities [10]. While both methods efficiently profiled over 300 lipids across major lipid classes in plasma samples, the untargeted approach identified a broader range of molecular species, including ether-linked phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylinositols (PIs). The targeted Lipidyzer platform excelled at quantifying free fatty acids (FFA) and cholesterol esters (CE) with high precision. When used together, these approaches can detect up to 700 lipid molecular species in mouse plasma, significantly expanding lipid coverage [10].

Experimental Protocols in Diabetes Lipidomics

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

Standardized sample preparation is critical for reproducible lipidomics results. In studies of T2DM patients and model systems, the methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)/methanol extraction method has been widely adopted for its effectiveness in extracting both polar and nonpolar metabolites with high recovery rates and low coefficient of variation [11]. The typical protocol involves:

- Sample Handling: Serum or plasma samples are thawed at room temperature, vortexed, and aliquoted (typically 30 μL) [2].

- Protein Precipitation: Addition of 200 μL methanol containing internal standards (e.g., LysoPC(17:0), PC(17:0/17:0), TG(17:0/17:0/17:0)) [2].

- Lipid Extraction: Introduction of 660 μL MTBE and 150 μL water, followed by vigorous vortexing for 5 minutes [2] [11].

- Phase Separation: Centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate organic and aqueous phases [2].

- Sample Concentration: Collection of the upper organic phase (600 μL) followed by vacuum concentration at 50°C [2].

- Reconstitution: The dried lipid extract is reconstituted in 600 μL of acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (65:30:5, v/v/v) mixture prior to LC-MS analysis [2].

This method demonstrates superior performance compared to alternative extraction systems using ethanol or chloroform, particularly in terms of extraction reproducibility and recovery [11].

Instrumental Analysis Conditions

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry parameters must be optimized for comprehensive lipid separation and detection:

Untargeted LC-MS Approach [2] [10]:

- Chromatography: Reverse phase C18 column with gradient elution

- Mass Detection: Quadrupole electrostatic field orbital trap high-resolution mass spectrometer (Q Exactive)

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative modes

- Scan Range: m/z 10-1200

- Data Acquisition: Data-dependent MS/MS scanning with collision energies of 20, 35, 50 eV

Targeted Lipidyzer Platform [10]:

- Separation: Differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) for lipid class separation

- Mass Detection: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) using low-resolution mass spectrometry

- Quantification: Based on a mixture of internal standards calibrated for fatty acid chain length and unsaturation diversity

Lipid Dysregulation in T2DM Pathogenesis

Key Lipid Alterations in Disease Progression

Integrated lipidomics approaches have revealed dynamic changes in lipid metabolism across different stages of T2DM. A comprehensive study analyzing serum samples from 155 subjects identified significant alterations in 44 lipid metabolites in newly diagnosed T2DM patients and 29 lipid species in high-risk individuals compared to healthy controls [2]. These changes disrupted several key metabolic pathways, including sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, and sterol ester metabolism, highlighting their involvement in insulin resistance and oxidative stress mechanisms in T2DM progression [2].

Table 2: Key Lipid Species Altered in T2DM Pathogenesis

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Species | Alteration in T2DM | Potential Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipids | PC(18:0_22:4), LPC(14:0) | Downregulated [6] | Impaired membrane structure, signaling |

| Glycerophospholipids | PE(16:118:2), PE(18:022:4) | Downregulated [6] | Disrupted mitochondrial function |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramides | Upregulated [12] | Promotes insulin resistance, inflammation |

| Glycerolipids | Triacylglycerols (TAG) | Upregulated [2] [10] | Ectopic lipid accumulation, lipotoxicity |

| Fatty Acyls | Free fatty acids (FFA) | Upregulated [9] | Impairs insulin signaling pathways |

| Sterol Lipids | Cholesterol esters (CE) | Altered [2] | Disrupted cholesterol homeostasis |

Notably, 13 lipid metabolites exhibited consistent trends of increase or decrease as T2DM progressed, suggesting their potential utility as biomarkers for disease monitoring [2]. In non-human primate models of T2DM, combined untargeted and targeted approaches identified four specific downregulated lipid species—PC(18:022:4), LPC(14:0), PE(16:118:2), and PE(18:0_22:4)—as potential biomarkers, with glycerophospholipid metabolism emerging as a key disrupted pathway [6].

Mechanisms Linking Lipid Dysregulation to Insulin Resistance

The pathological connection between lipid dysregulation and T2DM manifestations involves multiple interconnected mechanisms:

Lipotoxicity and Ectopic Lipid Accumulation: Under conditions of chronic nutrient excess, excessive lipid accumulation beyond the storage capacity of adipose tissue leads to ectopic deposition in liver, skeletal muscle, and pancreatic islets [9] [8]. This ectopic lipid accumulation results in lipotoxicity, characterized by the accumulation of bioactive lipid intermediates including diacylglycerols (DAG) and ceramides [12]. These intermediates disrupt intracellular insulin signaling pathways, particularly the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway, ultimately inducing insulin resistance [8] [12].

Lipid Droplet Dynamics and Organelle Interactions: Lipid droplets (LDs) are dynamic organelles that store neutral lipids and regulate cellular energy homeostasis [9]. In pancreatic β-cells, LDs normally participate in lipid metabolism that regulates insulin secretion while sequestering harmful lipids to protect against nutrient excess [9]. Under pathological conditions of T2DM, dysregulated LD dynamics—including impaired lipolysis and lipophagy—lead to excessive LD accumulation and loss of protective functions, contributing to β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis [9].

Inflammatory Pathways: Lipid dysregulation activates pro-inflammatory cascades through multiple mechanisms [12]. Accumulating lipid intermediates trigger inflammatory signaling pathways such as c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which further disrupts insulin receptor function and promotes metabolic stress [12]. Additionally, alterations in specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (SPMs) derived from ω-3 fatty acids impair the resolution of inflammation, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that sustains insulin resistance [13].

Diagram 1: Pathogenic cycle of lipid-induced insulin resistance in T2DM. Lipid dysregulation creates a self-reinforcing cycle that drives disease progression.

Signaling Pathways in Lipid-Mediated Insulin Resistance

The molecular mechanisms linking lipid dysregulation to impaired insulin action involve several key signaling pathways that are interconnected at multiple levels:

PI3K/Akt Insulin Signaling Pathway: Under physiological conditions, insulin binding to its receptor activates IRS-1, which subsequently triggers PI3K/Akt signaling [8]. Activated Akt promotes glucose uptake via GLUT4 translocation, inhibits gluconeogenesis by phosphorylating FOXO1, and enhances glycogen synthesis through GSK3 inactivation [8]. Lipid intermediates such as DAG and ceramides disrupt this pathway at multiple points, primarily by impairing IRS-1 function through phosphorylation and inhibiting Akt activation [8] [12].

AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) Pathway: AMPK serves as a central energy sensor that regulates lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity [12]. Under conditions of energy surplus, AMPK activation promotes fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis while inhibiting lipid synthesis. Lipid overload can disrupt AMPK signaling, contributing to lipid accumulation and insulin resistance [12].

Inflammatory Signaling Pathways: JNK and IKKβ/NF-κB pathways are activated by lipid excess and promote insulin resistance through serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins, which inhibits their function and downstream insulin signaling [12]. These pathways also induce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines that further exacerbate metabolic dysfunction [12].

Diagram 2: Key signaling pathways in lipid-mediated insulin resistance. Lipid intermediates disrupt normal insulin signaling through multiple mechanisms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Diabetes Lipidomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | LysoPC(17:0), PC(17:0/17:0), TG(17:0/17:0/17:0) [2] | Lipid quantification | Enable absolute quantification by correcting for variability in extraction and ionization |

| Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), methanol, water [2] [11] | Lipid extraction | Efficient separation of lipid classes with high recovery and reproducibility |

| LC-MS Mobile Phases | Acetonitrile, isopropanol, ammonium formate, formic acid [2] | Chromatographic separation | Optimize lipid separation and ionization efficiency in MS detection |

| Lipid Standards | Sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, sterol ester standards [2] | Method calibration | Validate identification and quantification across lipid classes |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | LimeMap, CellDesigner, VANTED [13] | Data visualization | Map lipid mediator pathways and visualize experimental data in biological context |

| Bioinformatics Resources | KEGG, LIPID MAPS, HMDB [13] | Lipid identification and pathway analysis | Reference databases for structural information and metabolic pathways |

The integration of targeted and untargeted lipidomics approaches has substantially advanced our understanding of lipid dysregulation in T2DM pathogenesis. These complementary methodologies have revealed dynamic alterations in lipid species across disease stages, identified potential biomarkers for early diagnosis, and uncovered novel therapeutic targets. The consistent findings across human studies and animal models highlight the central role of glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism in disease progression. Future research directions should focus on developing standardized protocols for cross-laboratory comparisons, expanding lipid coverage to include more specialized pro-resolving mediators, and integrating multi-omics data to build comprehensive models of metabolic dysregulation in T2DM. As lipidomics technologies continue to evolve, they hold significant promise for enabling personalized approaches to T2DM prevention and treatment based on individual lipidomic profiles.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from impaired insulin secretion and/or insulin resistance. The pathogenesis of T2D is influenced by a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, with dysregulated lipid metabolism now recognized as a central contributor to disease development and progression [2]. Lipids serve as essential components of cell membranes, energy storage molecules, and signaling mediators. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism, including alterations in lipid composition and signaling pathways, has been linked to insulin resistance and other metabolic abnormalities associated with T2D [2]. While previous studies have highlighted the role of lipid metabolism in T2D, a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic changes in lipid profiles throughout the disease process remains crucial for developing sensitive biomarkers for early diagnosis, effective therapeutic strategies, and improved disease management [2].

Modern lipidomics approaches have enabled precise quantification of individual lipid species in human plasma and tissues, revealing specific alterations in sphingolipids, phospholipids, and glycerolipids across different stages of diabetes progression. These lipid classes are no longer viewed as simple structural components or energy stores but as dynamic mediators of cellular signaling with profound impacts on insulin sensitivity, β-cell function, and complication development. This review synthesizes current evidence from targeted and untargeted lipidomics studies to compare and contrast the roles of these key lipid classes in diabetes pathophysiology, with particular emphasis on their potential as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Methodological Approaches: Targeted vs. Untargeted Lipidomics

Lipidomics investigates the diversity, functional dynamics, and biological significance of lipid species within living systems. Based on methodological frameworks and research objectives, this field bifurcates into two paradigms: untargeted lipidomics (hypothesis-generating) and targeted lipidomics (hypothesis-driven). These approaches diverge markedly in their conceptual frameworks, analytical objectives, technological requirements, and sample preparation methodologies, while sharing foundational principles in lipid characterization [1].

Untargeted lipidomics employs a holistic analytical strategy to profile the complete lipid repertoire within biological specimens. Utilizing high-resolution mass spectrometry coupled with chromatographic separation, this hypothesis-free approach systematically identifies and quantifies lipid species without prior selection of targets. It serves as a discovery tool to map lipid diversity, uncover novel metabolic pathways, and elucidate lipid functional networks across biological systems. The distinctive attributes of untargeted lipidomics include comprehensive profiling capability, high-throughput capacity, and significant discovery potential for identifying novel biomarkers and lipid-protein interactions [1].

Targeted lipidomics adopts a hypothesis-driven methodology, focusing on precise quantification of predefined lipid panels. Leveraging techniques such as Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), this approach prioritizes analytical rigor for specific lipid classes or molecules, delivering absolute quantification via internal standards. It is optimized for validating biomarkers, monitoring metabolic fluxes, and assessing therapeutic interventions. The key strengths of targeted lipidomics include exceptional analytical precision, selective detection, quantitative rigor, and enhanced clinical utility for diagnostic applications and therapeutic monitoring [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Approaches

| Dimension | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning Mode | Full Scan + Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Selective Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM) or Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) |

| Target Scope | Global coverage (>1,000 lipids) | Specific targets (<100 lipids) |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative (relative quantification via internal standards) | Absolute quantification (standard curve method, down to fg-level sensitivity) |

| Data Depth | High (novel lipid discovery enabled) | Low (limited to pre-defined targets) |

| Instrument Configuration | Q-TOF, Orbitrap (high resolution) | Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) |

| Typical Applications | Biomarker discovery, metabolic pathway analysis | Clinical diagnostics validation, drug pharmacokinetics monitoring |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Untargeted Lipidomics Workflow: Sample preparation typically involves total lipid extraction using methods like methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) extraction coupled with deproteinization [2]. For serum samples, 30 μL of serum is mixed with 200 μL of methanol containing internal standards, followed by addition of 660 μL of MTBE and 150 μL of water [2]. After vortexing and centrifugation, the upper organic phase is concentrated to dryness and reconstituted for analysis. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis is performed using high-resolution instruments such as quadrupole electrostatic field orbital trap high-resolution mass spectrometry systems, with data acquired in both positive and negative ion modes [2]. Data processing involves feature detection and alignment using tools like XCMS Online, followed by structural elucidation through multi-tier annotation and statistical exploration via multivariate methods.

Targeted Lipidomics Workflow: Target selection prioritizes lipids based on biological relevance, followed by parameter optimization for collision energy and ion transitions using reference standards [1]. Sample pretreatment often includes solid-phase extraction to enrich target lipids while reducing matrix complexity. Data acquisition utilizes internal standard quantification with isotope-labeled analogs to normalize analyte signals, with quality assurance validated via recovery rates and precision measurements using quality control samples [1].

Sphingolipids in Diabetes Pathophysiology

Sphingolipids represent a major class of lipids that are ubiquitous components of eukaryotic cells where they play important roles as building blocks of biological membranes and as bioactive molecules controlling critical cellular functions, including the cell cycle, senescence, apoptosis, cell migration, and inflammation [14]. Multiple studies conducted in the past decades have revealed that members of the sphingolipid family, including ceramide, sphingosine, sphingosine-1 phosphate, and ceramide-1-phosphate act as bioactive molecules that control numerous signal transduction pathways [14].

Ceramides: Central Mediators of Insulin Resistance

Ceramides have emerged as particularly important mediators of insulin resistance through multiple mechanisms. Tissue accumulation of ceramides impairs insulin signaling and induces pancreatic β-cell apoptosis, with consequent glucose dysregulation [15]. Ceramides can directly inhibit insulin signaling through two major mechanisms: activation of protein phosphatase A2 (PP2A) which dephosphorylates Akt/PKB at T308 moiety, and blocking the translocation of serine/threonine kinase Akt/PKB to the plasma membrane via a mechanism based on atypical protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ) [14]. In skeletal muscles, increased deposition of ceramide leads to insulin resistance development, with specific ceramide species (18:0, 22:0, 24:0, 24:1) significantly elevated in prediabetic models [16].

The impact of ceramides extends to hepatic insulin resistance, where they impair hepatic insulin signaling through direct activation of PKCζ or PP2A which decrease phosphorylation of Akt2 mainly in the Ser474 and Thr309 phosphorylation sites, subsequently inhibiting insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis [17]. Recent studies in animal models demonstrate that ceramide accumulation in the liver exacerbates hepatic insulin resistance, while interventions that reduce ceramide levels improve insulin sensitivity [17].

Table 2: Ceramide Species Altered in Diabetes and Associated Complications

| Ceramide Species | Change in Diabetes | Biological Significance | Associated Complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cer(d18:0/22:0) | Decreased in retinopathy [18] | Independent risk factor for DR occurrence | Diabetic retinopathy |

| Cer(d18:0/24:0) | Decreased in retinopathy [18] | Independent risk factor for DR occurrence | Diabetic retinopathy |

| Cer(18:0) | Increased in muscle [16] | Contributes to skeletal muscle insulin resistance | Insulin resistance |

| Cer(22:0) | Increased in muscle [16] | Marker of prediabetic insulin resistance | Insulin resistance |

| Cer(24:0) | Increased in muscle [16] | Associated with impaired glucose tolerance | Insulin resistance |

| Cer(24:1) | Increased in muscle [16] | Correlated with hypertriglyceridemia | Insulin resistance |

Sphingomyelins and Their Dual Roles

Sphingomyelins demonstrate more complex associations with metabolic parameters. Several studies have revealed that very-long-chain (VLC) sphingomyelins (C28-C34) are significantly associated with insulin sensitivity in normoglycemic adults [15]. In contrast, long-chain sphingomyelins typically show inverse relationships with insulin sensitivity, highlighting the importance of considering chain length and saturation when evaluating sphingolipid functions [15].

In the context of diabetic complications, specific sphingomyelins show altered patterns. In diabetic retinopathy, SM(d18:1/24:1) is significantly decreased, while other sphingomyelin species are elevated [18]. These changes suggest compartmentalized and specific roles for different sphingomyelin species in the development and progression of diabetes complications.

Sphingolipids in Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Sphingolipids, in addition to their direct impact on the insulin signaling pathway, may be responsible for other negative aspects of diabetes, namely mitochondrial dysfunction and deficiency [14]. Mitochondrial health, characterized by appropriate mitochondrial quantity, oxidative capacity, controlled oxidative stress, undisturbed respiratory chain function, ATP production, and mitochondrial proliferation through fission and fusion, is impaired in the skeletal muscles and liver of T2D subjects [14]. Recent findings suggest that impaired mitochondrial function may play a key role in the development of insulin resistance.

Ceramides have been demonstrated to negatively affect mitochondrial respiratory chain function and fission/fusion activity. Using LC-MS profiling, researchers have identified multiple unique ceramide, sphingomyelin, and ganglioside species in liver mitochondria [14]. The presence of enzymes in the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway, including ceramide synthase, ceramidase, sphingomyelinase, and sphingosine kinase, has been detected in mitochondria, indicating local sphingolipid metabolism within this organelle [14].

Phospholipids: Membrane Dynamics and Signaling in Diabetes

Phospholipids are the major structural components of cellular membranes and play crucial roles in maintaining membrane integrity, fluidity, and permeability. The two major classifications of phospholipids are glycerophospholipids and sphingophospholipids [19]. Glycerophospholipids comprise glycerol, saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, phosphoric acid, and a nitrogenous base, and are subdivided into phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylglycerol, and phosphatidic acid [19]. These phospholipids are altered by the type of disease or disease progression, with metabolomics studies revealing that phospholipids and their metabolites have potential as diagnostic biomarkers for human diseases, including diabetes and its complications [19].

Phosphatidylcholines and Lysophosphatidylcholines

Phosphatidylcholine is the most abundant phospholipid in mammalian cell membranes and is derived from choline primarily via the cytidine diphosphate-choline pathway [19]. Lysophosphatidylcholine, derived from the cleavage of PC, is associated with the occurrence of several diseases such as atherosclerosis and calcification [19]. In diabetes, specific changes in PC and LPC profiles have been observed across different tissues and complications.

In skeletal muscle insulin resistance, lipidomic profiling has revealed decreases in membrane phospholipids, including specific phosphatidylethanolamine and lysophosphatidylcholine species [16]. These alterations in membrane phospholipid composition may affect membrane fluidity and receptor signaling, contributing to insulin resistance development. In diabetic retinopathy, one phosphatidylcholine and two lysophosphatidylcholines were significantly elevated in patients with DR compared to those without retinopathy [18].

Phosphatidylethanolamines and Phosphatidylinositols

Phosphatidylethanolamine is the second most abundant phospholipid in mammalian cells and acts as a substrate for posttranslational modifications, influences membrane topology, and promotes cell and organelle membrane fusion, oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and autophagy [19]. In the context of diabetes, reduced PE levels have been associated with obesity and metabolic dysfunction.

Although phosphatidylinositol is a minor anionic lipid in mammalian cells, it plays a key role in regulating cellular signaling events and development of human diseases [19]. PI biosynthesis is catalyzed by enzymes localized at the ER, and phosphorylated forms of PI known as phosphoinositides are crucial for insulin signaling and glucose metabolism through their roles in vesicular trafficking and membrane receptor function.

Table 3: Phospholipid Alterations in Diabetes and Associated Conditions

| Phospholipid Class | Specific Species | Change in Diabetes | Associated Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | Multiple species | Decreased in sepsis [19] | Sepsis, systemic inflammation |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) | LPC(22:6) | Decreased in muscle [16] | Skeletal muscle insulin resistance |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | PE(41:2) | Decreased in muscle [16] | Skeletal muscle insulin resistance |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) | LPE(20:0) | Decreased in muscle [16] | Skeletal muscle insulin resistance |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Various phosphorylated forms | Altered signaling | Insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction |

Glycerolipids: Energy Storage and Lipotoxicity

Glycerolipids, particularly triacylglycerols and diacylglycerols, play central roles in energy storage and metabolic regulation. In the context of diabetes, impaired lipid metabolism contributes to both the onset and progression of T2DM, with elevated plasma triglycerides and non-esterified fatty acids closely associated with decreased insulin sensitivity in human studies [16]. Dyslipidemia and lipid excess lead to the accumulation of intramyocellular lipid metabolites, which coincides with impaired insulin response.

Diacylglycerols and Insulin Resistance

Diacylglycerols have been extensively studied for their role in insulin resistance development through activation of protein kinase C isoforms. In skeletal muscle insulin resistance, accumulation of 1,3-diacylglycerols is associated with impaired insulin sensitivity in prediabetic models [16]. DAGs activate conventional and novel protein kinase C isoforms, which in turn serine-phosphorylate insulin receptor substrate-1, reducing its ability to activate downstream PI3K/Akt signaling.

The subcellular localization and fatty acyl composition of DAG species appear to determine their signaling potency. Certain membrane-associated DAG species with specific fatty acid compositions are more potent activators of PKC isoforms linked to insulin resistance. This specificity may explain why total DAG content does not always correlate with insulin resistance across different physiological and pathological conditions.

Triacylglycerols and Ectopic Fat Storage

While triacylglycerols themselves are not directly lipotoxic, their accumulation in non-adipose tissues serves as a marker of lipid overflow and is closely associated with insulin resistance. Skeletal muscle TG accumulation is associated with insulin resistance in various animal models, including obese non-diabetic, diabetic rat models, as well as in non-obese prediabetic hereditary hypertriglyceridemic rat strains [16]. The role of triglycerides as a risk factor for diabetes progression is well established in large clinical studies.

The relationship between triglycerides and insulin resistance is complex, as TG molecules themselves primarily serve as inert energy storage. However, the processes leading to TG accumulation often involve increased flux of fatty acids into tissues and subsequent esterification, which shares precursors with other lipid species that are directly involved in disrupting insulin signaling, such as diacylglycerols and ceramides.

Analytical Toolkit for Diabetes Lipidomics Research

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Diabetes Lipidomics Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | Absolute quantification in targeted lipidomics | LysoPC(17:0), PC(17:0/17:0), TG(17:0/17:0/17:0), SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard [2] [18] |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Lipid extraction from biological samples | HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, isopropanol, methyl tert-butyl ether [2] |

| Chromatography Columns | Lipid separation prior to mass spectrometry | C18 reversed-phase columns (e.g., CSH C18, 1.7 μm 2.1×100 mm) [18] |

| Albumin Preparations | Fatty acid delivery in cell culture studies | Fatty acid-free BSA, charcoal-absorbed BSA for complexing FFAs [20] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring analytical performance | Pooled serum QC samples, reference standards [2] |

Methodological Considerations for Lipid Studies

When conducting lipid studies in diabetes research, several methodological aspects require careful consideration. For cell culture studies, particularly those investigating lipid effects on pancreatic β-cells, the concentration and presentation of free fatty acids are critical factors. Commercial bovine serum albumin may contain variable amounts of endogenous FFAs, potentially confounding experimental results [20]. Charcoal treatment of BSA or using commercially available FFA-free albumin preparations helps standardize FFA delivery.

The molar ratio of FFAs to albumin is a crucial parameter determining the concentration of unbound FFAs, which represent the biologically active fraction. For palmitate, a 0.5 mM solution with an FFA/albumin molar ratio of 3.3:1 has a theoretical unbound concentration of 27 nM, while similar preparation of oleate has an unbound concentration of 47 nM due to different binding affinities [20]. These differences in unbound concentrations should be considered when comparing effects of different fatty acid species.

The comprehensive analysis of sphingolipids, phospholipids, and glycerolipids in diabetes reveals complex and interconnected roles for these lipid classes in disease pathogenesis. Sphingolipids, particularly ceramides, emerge as central mediators of insulin resistance through their direct effects on insulin signaling pathways and mitochondrial function. Phospholipids demonstrate important structural and signaling roles, with specific species showing altered patterns in diabetes and its complications. Glycerolipids contribute to metabolic dysregulation through ectopic storage and generation of lipid intermediates that disrupt insulin action.

The complementary approaches of targeted and untargeted lipidomics have proven invaluable in advancing our understanding of lipid dynamics in diabetes. Untargeted methods enable discovery of novel lipid biomarkers and pathways, while targeted approaches provide precise quantification of specific lipid species relevant to disease mechanisms. The continuing evolution of lipidomics technologies promises further insights into the intricate relationships between lipid metabolism and diabetes pathophysiology, potentially leading to improved diagnostic strategies and therapeutic interventions for this complex metabolic disorder.

Lipidomics has emerged as a powerful tool for uncovering novel biomarkers and elucidating metabolic dysregulation in type 2 diabetes (T2D). This comparison guide examines how untargeted and targeted lipidomics approaches contribute to diabetes research, highlighting their complementary strengths in biomarker discovery and validation. Through analysis of recent studies and experimental data, we demonstrate that untargeted lipidomics provides comprehensive lipid profiling that reveals early metabolic shifts in high-risk individuals, while targeted approaches enable precise quantification of validated biomarkers. This systematic evaluation of methodologies, findings, and practical applications provides researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate lipidomics strategies based on their specific research objectives in diabetes biomarker investigation.

Type 2 diabetes is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from impaired insulin secretion and/or insulin resistance, with growing evidence suggesting the central role of lipid metabolism in its pathogenesis [21] [2]. The often asymptomatic nature of T2D during early stages presents a significant challenge, leading to delayed diagnosis and increased risk of complications [2]. Lipidomics—the large-scale study of pathways and networks of cellular lipids in biological systems—has opened new avenues for understanding the dynamic changes in lipid metabolism across different stages of T2D [22] [23].

The transition from traditional lipid biochemistry to comprehensive lipid profiling represents a paradigm shift in metabolic disease research [24]. Lipids are no longer viewed merely as structural components and energy storage molecules but are increasingly recognized as bioactive molecules that regulate inflammation, metabolic homeostasis, and cellular signaling [22]. The dysregulation of lipid metabolism, including alterations in lipid composition and signaling pathways, has been linked to insulin resistance and other metabolic abnormalities associated with T2D [2]. This guide systematically compares untargeted and targeted lipidomics approaches, providing researchers with experimental data, methodological protocols, and analytical frameworks to advance biomarker discovery in diabetes research.

Comparative Analysis: Untargeted vs. Targeted Lipidomics

Untargeted and targeted lipidomics represent complementary approaches with distinct methodological frameworks and applications [23]. Understanding their fundamental differences enables researchers to select appropriate strategies for specific research questions in diabetes investigation.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics

| Characteristic | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Comprehensive biomarker discovery [23] | Hypothesis-driven validation [23] |

| Analytical Approach | Global profiling without predefined targets [23] | Quantification of predefined lipid species [23] |

| Typical Workflow | Sample preparation → LC-MS analysis → Data processing → Lipid identification → Statistical analysis [23] | Sample preparation + internal standards → LC-MRM/MS → Peak integration → Quantitative analysis [23] |

| Data Output | Relative quantification of all detected lipids [23] | Absolute quantification of targeted lipids [23] |

| Key Advantage | Unbiased discovery of novel lipids [23] | High sensitivity and accurate quantification [23] |

| Main Limitation | Complex data analysis; semi-quantitative [23] | Limited to predefined lipids; potentially missing novel findings [23] |

| Ideal Application in Diabetes Research | Identifying novel lipid alterations in early diabetes stages [21] [2] | Validating candidate biomarkers across larger cohorts [21] |

A cross-platform comparison study revealed that while both approaches detect similar numbers of lipids (337 vs. 342 lipid species in mouse plasma), untargeted LC-MS identifies a broader range of lipid classes and provides more detailed structural information for complex lipids like triacylglycerols [10]. The same study reported a median correlation coefficient of 0.71 between quantitative measurements from both platforms when applied to endogenous plasma lipids in aging mice, indicating generally consistent but not identical results [10].

Experimental Findings in Type 2 Diabetes Research

Key Lipid Alterations in Diabetes Progression

A 2024 study employing both untargeted and targeted lipidomics analyzed serum samples from 155 subjects across different disease stages: healthy controls, high-risk individuals, newly diagnosed T2D patients, and patients with more than two years of T2D duration [21] [2]. The research identified significant alterations in 44 lipid metabolites in newly diagnosed T2D patients and 29 in high-risk individuals compared with healthy controls [21] [2]. These findings demonstrate the sensitivity of lipidomics, particularly untargeted approaches, in detecting metabolic shifts before full disease manifestation.

Table 2: Significant Lipid Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Progression

| Lipid Class | Specific Lipid Species | Alteration Pattern | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sphingomyelins | Multiple species (e.g., SM(d38:1)) | Significantly disrupted in T2D [21] | Involvement in insulin resistance pathways [21] |

| Phosphatidylcholines | Multiple species | Significantly disrupted in T2D [21] | Membrane integrity and signaling functions [21] |

| Sterol Esters | Multiple species | Significantly disrupted in T2D [21] | Cholesterol metabolism and storage implications [21] |

| Triacylglycerols | Multiple species (e.g., TAG52:3-FA16:0) | Most changed lipid class in longitudinal studies [10] | Particularly sensitive to metabolic changes [10] |

| 13 Lipid Metabolites | Unspecified in abstract | Consistent increasing/decreasing trends with progression [21] | Strong diagnostic potential for T2D monitoring [21] |

The study further identified 13 lipid metabolites with consistent trends of increase or decrease as diabetes progressed, highlighting their potential diagnostic value for disease monitoring [21]. Key metabolic pathways including sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, and sterol ester metabolism were disrupted across disease stages, underscoring the involvement of insulin resistance and oxidative stress in T2D progression [21].

Methodological Protocols for Diabetes Lipidomics

Sample Preparation Protocol

The experimental protocol from the 2024 T2D lipidomics study exemplifies standardized methodology [2]:

- Sample Collection: Fasting blood samples collected from all subjects, with serum immediately prepared by centrifuging at 4000 rpm and stored at -80°C until analysis [2].

- Lipid Extraction: 30 μL of serum mixed with 200 μL of methanol containing 1 μg/mL of internal standards (LysoPC(17:0), PC(17:0/17:0), and TG(17:0/17:0/17:0)), followed by addition of 660 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether and 150 μL of water [2].

- Processing: Samples vortexed for 5 minutes, stood for 5 minutes, then centrifuged at 8°C and 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes [2].

- Preparation for Analysis: 600 μL of the upper organic phase concentrated to dryness in a vacuum centrifuge concentrator at 50°C, then reconstituted with 600 μL of acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (65:30:5, v/v/v) mixture [2].

Instrumental Analysis Parameters

- Untargeted Approach: Utilized quadrupole electrostatic field orbital trap high-resolution mass spectrometry system (Q Exactive) with ESI source [2]. Data acquired in both positive and negative ion modes with spray voltage 3.5/-3.5 kV, capillary temperature 450°C, sheath gas flow rate 60 arbitrary units, and scan range m/z 10-1200 [2].

- Targeted Validation: Employed liquid chromatography coupled with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for precise quantification of identified potential biomarkers [23].

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Lipid Biomarker Discovery and Validation in Diabetes Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Diabetes Lipidomics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Application Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | HPLC-grade acetonitrile, isopropanol, methanol, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [2] | Lipid extraction from biological samples [2] [23] | Proper solvent ratios critical for extraction efficiency [2] |

| Internal Standards | LysoPC(17:0), PC(17:0/17:0), TG(17:0/17:0/17:0) [2] | Quantification normalization and quality control [2] [23] | Stable isotope-labeled standards preferred for targeted work [23] |

| Chemical Modifiers | Formic acid, ammonium formate [2] | Enhance ionization in mass spectrometry [2] | Concentration optimization improves signal response [2] |

| Lipid Standards | 17 lipid standards covering fatty acids, glycerolipids, sphingolipids, glycerophospholipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids [2] | Method validation and calibration [2] | Should cover major lipid classes relevant to diabetes [2] |

| Chromatography Columns | Reversed-phase C18 columns [23] | Separation of complex lipid mixtures [23] | Column chemistry affects lipid separation selectivity [23] |

Data Visualization and Analysis in Lipidomics

Effective data visualization is crucial for interpreting complex lipidomics datasets. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots effectively display sample clustering and group separations, revealing patterns related to disease states [25]. Heatmaps with hierarchical clustering visualize abundance patterns of multiple lipid species across sample groups, while volcano plots effectively highlight lipids with both statistical significance and substantial fold changes between experimental conditions [25].

The 2024 T2D study employed multivariate statistical analysis, dynamic change trend analysis, and ROC analysis to identify potential biomarkers for early diagnosis and disease monitoring [2]. These bioinformatics approaches are essential for translating raw lipidomics data into biologically meaningful insights.

Figure 2: Progressive Lipid Metabolism Disruption in Type 2 Diabetes Development

The integration of untargeted and targeted lipidomics provides a powerful framework for advancing diabetes research and clinical applications. Untargeted lipidomics excels in revealing early metabolic shifts and discovering novel biomarker candidates, while targeted approaches enable precise validation and quantification of these findings across larger cohorts [21] [2] [23]. The identification of 44 significantly altered lipid metabolites in newly diagnosed T2D patients and 29 in high-risk individuals demonstrates the sensitivity of these approaches in detecting metabolic dysregulation before full disease manifestation [21] [2].

Future directions in diabetes lipidomics research include the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning frameworks to enhance lipid identification and biomarker prediction [24]. Additionally, addressing challenges in standardization, inter-laboratory reproducibility, and clinical validation will be crucial for translating lipidomics findings into clinically useful diagnostic tools [22] [24]. As lipidomics technologies continue to evolve, they hold significant promise for advancing personalized medicine approaches in diabetes management through improved risk assessment, early diagnosis, and monitoring of therapeutic interventions [21] [22].

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represents a global metabolic health crisis, with its pathogenesis deeply rooted in systemic lipid metabolic dysregulation. This case study explores the dynamic lipid alterations across different stages of T2DM progression through the integrated application of targeted and untargeted lipidomics approaches. The comparative analysis of these methodological paradigms reveals their synergistic potential in uncovering the complex lipid rewiring that characterizes diabetes progression, from pre-diabetic states to advanced disease. By framing this investigation within the broader thesis of targeted versus untargeted lipidomics research, we demonstrate how each approach contributes unique insights into T2DM pathophysiology, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic targeting, providing drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for metabolic disease investigation.

Methodological Frameworks: Targeted vs. Untargeted Lipidomics

Lipidomics investigation bifurcates into two complementary paradigms: untargeted (hypothesis-generating) and targeted (hypothesis-driven) approaches. These methodologies diverge markedly in their conceptual frameworks, analytical objectives, and technological requirements while sharing foundational principles in lipid characterization [1].

Core Technical Principles and Instrumentation

Untargeted lipidomics employs a holistic analytical strategy to profile the complete lipid repertoire within biological specimens without prior selection of targets. This approach utilizes high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) platforms such as Q-TOF or Orbitrap instruments, achieving resolutions exceeding 120,000 FWHM with sub-1 ppm mass accuracy. The scanning mode typically involves full-spectrum acquisition (m/z 50-2000) with data-dependent acquisition (DDA) to enhance structural elucidation [1].

Targeted lipidomics adopts a hypothesis-driven methodology focusing on precise quantification of predefined lipid panels. This approach leverages triple quadrupole (QQQ) mass spectrometers operating in Selective Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM) or Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) modes. These instruments monitor specific precursor-to-product ion transitions to isolate target signals while filtering background noise, achieving sub-nanomolar sensitivity for low-abundance lipids [1].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Approaches

| Dimension | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning Mode | Full Scan + Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Selective Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM) or Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) |

| Target Scope | Global coverage (>1,000 lipids) | Specific targets (<100 lipids) |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative (relative quantification via internal standards) | Absolute quantification (standard curve method, down to fg-level sensitivity) |

| Instrument Configuration | Q-TOF, Orbitrap (high resolution) | Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) |

| Typical Applications | Biomarker discovery, metabolic pathway analysis | Clinical diagnostics validation, drug pharmacokinetics monitoring |

| Advantages | Unbiased, high discovery power | High sensitivity, precise quantification |

| Limitations | Low quantitative accuracy, dependent on database coverage | Poor scalability, inability to detect novel lipids |

Integrated Workflow for T2DM Investigation

A representative integrated lipidomics workflow for T2DM research begins with untargeted analysis to discover broadly altered lipid species across disease stages, followed by targeted validation of promising biomarkers using absolute quantification. This synergistic approach maximizes both discovery power and analytical rigor [2].

Experimental Data: Lipid Trajectories Across T2DM Progression

Study Population and Design

A comprehensive lipidomics investigation analyzed serum samples from 155 male subjects aged 35-65 years categorized into four distinct groups: healthy controls (Control, n=40), high-risk individuals (HR, n=40) with impaired glucose tolerance, newly diagnosed T2DM patients (NDT2D, n=39), and established T2DM patients with more than two years disease duration (MTYT2D, n=36). This longitudinal design enabled tracking lipid dynamics across the disease spectrum [2].

Table 2: Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants Across T2DM Progression

| Parameter | Control Group | HR Group | NDT2D Group | MTYT2D Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 40 | 40 | 39 | 36 |

| Age (years) | 53.7 ± 7.0 | 53.4 ± 6.1 | 50.2 ± 8.0 | 51.7 ± 10.8 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.4 ± 0.6 | 26.4 ± 0.9* | 25.6 ± 5.3* | 26.5 ± 3.9* |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 4.87 ± 0.65 | 5.23 ± 0.98* | 10.3 ± 3.59*### | 8.24 ± 2.41*& |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.65 ± 0.22 | 6.13 ± 0.20* | 8.16 ± 2.59*### | 7.88 ± 1.85* |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.73 ± 0.91 | 4.23 ± 0.87 | 4.74 ± 1.11* | 4.87 ± 1.03* |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.19 ± 0.59 | 1.40 ± 0.59 | 2.45 ± 2.02*## | 2.16 ± 2.08 |

Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, p < 0.01, *p < 0.001 vs. control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. HR group; &p < 0.05 vs. NDT2D group.

Key Lipid Alterations Across Disease Stages

The integrated lipidomics approach identified significant alterations in 44 lipid metabolites in NDT2D patients and 29 in high-risk individuals compared with healthy controls. Thirteen lipid metabolites exhibited consistent directional trends (increase or decrease) as T2DM progressed, highlighting their potential as progression biomarkers [2].

Specifically, glycerophospholipid metabolism emerged as significantly perturbed, with phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) showing marked alterations. In patients with diabetes combined with hyperuricemia, 13 triglycerides (TGs), 10 PEs, and 7 PCs were significantly upregulated, while select phosphatidylinositols (PIs) were downregulated [7].

Longitudinal deep lipidome profiling further revealed that individuals with insulin resistance exhibit disturbed immune homeostasis and accelerated changes in specific lipid subclasses during aging, including large and small triacylglycerols, ester- and ether-linked phosphatidylethanolamines, and ceramides [26].

Pathway Analysis of Lipid Dysregulation

Metabolic pathway analysis using platforms like MetaboAnalyst and KEGG identified glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) as the most significantly perturbed pathways in diabetic patients. These pathways play crucial roles in membrane integrity, signal transduction, and energy homeostasis, with their dysregulation contributing to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction [7].

Analytical Standards and Reagents

- Deuterated Internal Standards: Stable isotope-labeled analogs (e.g., ¹³C-PC 16:0/18:1, LysoPC (17:0), PC (17:0/17:0), TG (17:0/17:0/17:0)) for absolute quantification and correction of matrix effects [2].

- HPLC-grade Solvents: Acetonitrile, isopropanol, methanol, and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) for lipid extraction and chromatographic separation [2].

- Additives: Ammonium formate and formic acid for mobile phase optimization in LC-MS applications [2].

Instrumentation Platforms

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometers: Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (Thermo Fisher) and Q-TOF systems for untargeted analysis, achieving resolutions >120,000 FWHM with sub-1 ppm mass accuracy [1].

- Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometers: Sciex QTRAP systems operating in MRM/SRM mode for targeted quantification with sub-nanomolar sensitivity [1] [26].

- Chromatography Systems: UHPLC with C18 reversed-phase columns (e.g., Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18) for comprehensive lipid separation [7].

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis Tools

- LipidSearch: Commercial software for preprocessing both LC-MS and LC-MS/MS data, providing accurate peak-picking identification and integration [27].

- ADViSELipidomics: Shiny app for preprocessing, analyzing and visualizing lipidomics data, with unique capabilities for handling internal standards and generating normalized concentration values [27].

- MetaboAnalyst 5.0: Comprehensive platform for data standardization, pathway enrichment analysis, and multivariate statistical analysis [28].

- XCMS Online: Cloud-based platform for LC/MS data processing with peak detection, retention time alignment, and statistical analysis [1].

Discussion: Integrated Insights for T2DM Research and Drug Development

Complementary Value of Targeted and Untargeted Approaches

This case study demonstrates that untargeted and targeted lipidomics provide complementary insights into T2DM progression. The untargeted approach revealed extensive lipid alterations across multiple classes, identifying 44 significantly altered metabolites in newly diagnosed patients. The targeted approach then validated these findings with precise quantification, confirming 13 lipid metabolites with consistent progression trends [2]. This synergistic methodology offers both discovery power and analytical rigor, enabling comprehensive characterization of the T2DM lipidome.

The longitudinal deep lipidome profiling further highlighted the dynamic nature of lipid alterations in T2DM, with specific lipid subclasses showing accelerated changes during ageing in insulin-resistant individuals [26]. These findings underscore the importance of temporal sampling designs for capturing the evolving lipid landscape throughout disease progression.

Biological Significance of Lipid Alterations

The identified lipid alterations reflect fundamental pathophysiological processes in T2DM. Ceramides and diacylglycerols, significantly elevated in diabetic states, directly contribute to insulin resistance through inhibition of insulin signaling pathways [26]. Phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine imbalances disrupt membrane fluidity and function, affecting insulin secretion and glucose transport [7]. Triglyceride accumulation, particularly in ectopic tissues, drives lipotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction, further exacerbating metabolic impairment [9].

These lipid-mediated mechanisms represent promising therapeutic targets. Interventions that modulate specific lipid pathways—such as inhibiting ceramide synthesis or enhancing phospholipid remodeling—may offer novel approaches for T2DM management beyond conventional glycemic control.

Biomarker Translation and Clinical Applications

The consistent lipid alterations identified across T2DM stages hold significant potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. The 13 lipid metabolites showing progressive changes from high-risk to established diabetes could enable early detection and risk stratification [2]. Furthermore, the distinct lipid signatures in patients with diabetes complicated by hyperuricemia suggest specific biomarker panels for identifying diabetes subtypes and guiding personalized treatment strategies [7].

For drug development professionals, these lipid biomarkers offer valuable tools for patient selection, target engagement assessment, and treatment monitoring in clinical trials. The integration of lipidomic profiling into drug development pipelines could accelerate the identification of metabolic therapeutics and facilitate precision medicine approaches for T2DM management.

This case study demonstrates that dynamic lipid alterations are integral to T2DM pathophysiology and can be comprehensively characterized through integrated lipidomics approaches. The synergistic application of untargeted and targeted methodologies provides both discovery power and analytical precision, revealing lipid trajectories across disease progression and identifying potential biomarkers for early detection and monitoring. These findings advance our understanding of T2DM as a systemic metabolic disorder and provide a framework for future research and therapeutic development. As lipidomics technologies continue to evolve, their integration into diabetes research and clinical practice promises to transform our approach to this complex metabolic disease.

From Bench to Biomarker: Methodological Workflows and Diabetes-Specific Applications

In the context of diabetes research, the comprehensive and accurate identification of lipids is paramount for uncovering the metabolic dysregulations that characterize disease onset and progression. Untargeted lipidomics via Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) offers a powerful, hypothesis-generating approach, capable of profiling hundreds to thousands of lipid species simultaneously from a biological sample [2] [10]. However, a significant challenge persists: the confident identification of these lipids beyond their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). In a typical untargeted experiment, a vast number of features remain unknown, complicating biological interpretation [29]. This article delves into the modern untargeted workflow, objectively comparing advanced strategies and computational tools that are enhancing identification confidence, directly supporting biomarker discovery and pathogenic insights in diabetes research.

Core Untargeted Lipidomics Workflow: From Sample to Annotation

The standard untargeted workflow is a multi-stage process designed to maximize the detection and identification of lipids. The journey begins with meticulous sample preparation—a critical step for ensuring data quality. For instance, in studies of mouse models or human serum, this often involves liquid-liquid extraction methods using solvents like methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and methanol to efficiently recover a broad range of lipid classes [2] [10]. The extracted lipids are then separated by liquid chromatography, typically using reversed-phase columns, which resolves lipids based on their hydrophobicity [30].

Following separation, lipids are introduced into the high-resolution mass spectrometer, which detects ions based on their m/z with high accuracy and precision. Data acquisition in untargeted mode often employs data-dependent acquisition (DDA), where the most abundant ions from the MS1 scan are selectively fragmented to produce MS/MS spectra [31]. The final and most challenging step is the annotation of these acquired features. This involves matching the experimental data—precursor m/z, isotopic patterns, and MS/MS fragmentation spectra—against theoretical or empirical entries in lipid databases [31] [32]. The entire process is summarized in the workflow below.

Comparative Analysis of Lipid Identification Strategies

A key decision in the untargeted workflow is the choice of annotation strategy. Researchers must balance the need for broad, exploratory coverage with the demand for high-confidence identifications. The table below compares the core characteristics of three predominant approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Lipid Identification Strategies

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Typical Application in Diabetes Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted LC-HRMS [10] [31] | Unbiased detection of all detectable ions; annotation via database matching. | Broadest lipid coverage; discovery of novel biomarkers. | Lower confidence for annotations without MS/MS; complex data processing. | Hypothesis generation; global lipid dysregulation screening in T2DM [2]. |

| Targeted LC-MS/MS (e.g., Lipidyzer) [10] | Pre-defined list of lipids quantified using MRM and internal standards. | High throughput, excellent precision and accuracy, absolute quantification. | Limited to known lipids; narrower coverage. | Validation of specific lipid panels; tracking known T2DM biomarkers [6]. |

| Pseudo-Targeted Lipidomics [31] | Uses untargeted data to create a targeted MRM method for high-coverage quantification. | Combines wide coverage of untargeted with quantitative rigor of targeted. | Requires two instrumental analyses; method development is more complex. | Bridging discovery and validation phases; comprehensive biomarker verification. |

The Power of Integration: Untargeted and Targeted Approaches

The cross-platform comparison by [10] revealed that untargeted LC-MS and the targeted Lipidyzer platform, while each detecting a similar number of lipids (~340), showed limited overlap—only 196 lipid species were commonly identified. This highlights their complementary nature. The untargeted approach excelled in identifying a wider range of lipid classes, including ether-linked phosphatidylcholines (plasmalogens) and phosphatidylinositols. In contrast, the targeted platform uniquely detected specific free fatty acids and cholesteryl esters. When applied to aging mouse plasma, a model relevant to metabolic disease, both platforms concurred that triacylglycerols (TAG) were the most significantly altered lipid class, but the combined use of both approaches provided a more holistic view of the lipidomic landscape [10]. This synergistic strategy is highly applicable to diabetes research, where an untargeted screen on serum from diabetic cynomolgus monkeys identified 196 differential lipids, which were then narrowed down to four key biomarkers (e.g., PC(18:0_22:4), LPC(14:0)) for further validation using a targeted approach [6].

Enhancing Confidence with Machine Learning and Retention Time Prediction

A major frontier in untargeted lipidomics is the use of machine learning (ML) to improve identification accuracy. Since lipid fragmentation can be complex and instrument-dependent, supplementary data like retention time (RT) is crucial for reducing false positives [30] [33].

Machine Learning-Based Retention Time Prediction

Noreldeen et al. developed an ML model using Random Forest (RF) regression to predict lipid RTs based on molecular descriptors and fingerprints [30] [33]. The model was trained on a dataset of 286 lipids and tested on 142 lipids, separated on a reversed-phase C8 column with a 20-minute gradient. The performance was exceptional, demonstrating the power of ML to learn the complex relationship between a lipid's chemical structure and its chromatographic behavior.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of ML-Based Retention Time Prediction Model [30] [33]

| Dataset | Correlation Coefficient (R) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE, min) |

|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 0.998 | 0.107 |

| Test Set | 0.990 | 0.240 |

| External Validation | 0.991 | 0.241 |

The study found that molecular descriptors consistently outperformed molecular fingerprints when used with the RF algorithm [33]. Furthermore, the model demonstrated robustness by employing a calibration method that allowed for the transfer of predicted RTs between different chromatographic systems, enhancing its practical utility [30].

Classification and Advanced Annotation Tools

Beyond RT prediction, ML can classify features with minimal data. One study achieved high accuracy in distinguishing "lipids" from "non-lipids" using only m/z and RT as inputs to tree-based models, without requiring MS/MS data [29]. This can rapidly prioritize lipid features for downstream analysis.

Next-generation annotation platforms like LipidIN are pushing the boundaries further. This tool features a massive hierarchical library of 168.5 million theoretical lipid fragments and uses an "expeditious querying" module for ultra-fast searching [32]. A key innovation is its use of a lipid categories intelligence (LCI) module that applies three relative retention time rules to reduce false positives. LipidIN reported the ability to cover 8,923 lipids across various species with a low estimated false discovery rate of 5.7% [32]. The following diagram illustrates the logical framework of this integrated identification strategy.

Successful implementation of an untargeted lipidomics workflow relies on a suite of high-quality reagents, standards, and software. The following table details key solutions used in the experiments cited within this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LC-HRMS Lipidomics

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standard Mix | Corrects for extraction efficiency, ion suppression, and enables semi-quantification. A mix of stable isotope-labeled lipids is ideal. | Metabolomics QC kit with 14 labeled standards (e.g., L-Alanine-13C3, Stearic acid-13C18) [29]. |