The Double-Edged Sword: Balancing SOX9 Inhibition in Cancer with Tissue Repair Side Effects

SOX9 inhibition presents a promising therapeutic strategy for overcoming radioresistance and eradicating cancer stem cells in malignancies like gastrointestinal cancer.

The Double-Edged Sword: Balancing SOX9 Inhibition in Cancer with Tissue Repair Side Effects

Abstract

SOX9 inhibition presents a promising therapeutic strategy for overcoming radioresistance and eradicating cancer stem cells in malignancies like gastrointestinal cancer. However, this approach carries significant risks of impairing critical tissue repair mechanisms. This article synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that SOX9 suppression compromises stem cell functionality in skin wound healing, intestinal epithelium regeneration, cartilage maintenance, and vascular integrity. We explore methodological approaches for targeted inhibition, strategies to mitigate adverse effects, and comparative analyses across tissue types. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comprehensive review highlights the crucial balance between therapeutic efficacy and tissue toxicity, providing a framework for developing safer, more precise SOX9-targeted therapies.

SOX9's Essential Roles in Tissue Homeostasis and Regeneration

Molecular Characteristics of SOX9

What are the key structural features that enable SOX9's function as a transcription factor?

SOX9 is a 509-amino acid protein containing several functionally critical domains that facilitate its role as a transcription factor. The High Mobility Group (HMG) box domain is the defining feature that enables sequence-specific DNA binding to the consensus motif (A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G, bending DNA into an L-shaped complex and altering target gene expression. Other essential domains include: the dimerization domain (DIM) located upstream of the HMG domain that facilitates formation of homo- and heterodimers with other SOXE proteins; two transcriptional activation domains (TAM in the middle and TAC at the C-terminus) that interact with cofactors to enhance transcriptional activity; and a proline/glutamine/alanine (PQA)-rich domain that stabilizes the protein and enhances transactivation capabilities [1] [2] [3].

How is SOX9 activity regulated at the molecular level?

SOX9 undergoes extensive post-translational modifications that regulate its stability, intracellular localization, and transcriptional activity. Key regulatory mechanisms include phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) at serine residues S64 and S181, which enhances DNA-binding affinity and promotes nuclear translocation. SUMOylation can either enhance or repress SOX9 transcriptional activity depending on cellular context. Additionally, the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway degrades SOX9 in specific cell types like hypertrophic chondrocytes, and microRNAs post-transcriptionally inhibit SOX9 expression during lung development, chondrogenesis, and neurogenesis [2]. SOX9 typically functions by forming complexes with partner transcription factors, and its transcriptional output depends on both the specific binding sites and cofactors recruited in different cellular contexts [2].

SOX9 in Development and Stem Cell Biology

How does SOX9 function as a pioneer factor in cell fate determination?

Recent research has established SOX9 as a bona fide pioneer factor capable of binding to cognate motifs in closed chromatin and initiating cell fate switching. In skin reprogramming models, SOX9 binds to closed chromatin at hair follicle stem cell enhancers within one week of induction, before nucleosome displacement and chromatin opening occur. This pioneering activity enables SOX9 to divert embryonic epidermal stem cells into becoming hair follicle stem cells by simultaneously activating new enhancers while indirectly silencing previous epidermal enhancers through competition for limited epigenetic co-factors [4]. This fate-switching capability demonstrates SOX9's powerful role in developmental reprogramming.

What is SOX9's role in intestinal stem cell maintenance?

In the intestinal epithelium, SOX9 functions as a downstream target of Wnt signaling and helps maintain Wnt-dependent intestinal progenitors. SOX9 expression follows a gradient increasing from duodenum to distal colon and is restricted to the proliferative crypt zone in adults. It acts to repress differentiation genes including Cdx2 and Muc2, thereby maintaining progenitor cells in an undifferentiated state. Conditional inactivation studies demonstrate that SOX9 loss increases crypt cell proliferation and elevates expression of Wnt target genes cMYC and Cyclin D1, confirming its importance in intestinal stem cell regulation [5].

SOX9 in Tissue Repair and Regeneration

How does SOX9 contribute to regeneration after tissue injury?

SOX9-expressing cells demonstrate significant regenerative capacity across multiple tissue types. In radiation-induced lung injury models, SOX9-expressing cells promote regeneration of lung tissues, and their ablation leads to severe phenotypes after radiation damage. Lineage tracing in Sox9CreER; RosatdTomato mice revealed that SOX9+ cells are indispensable for repair and reconstruction following injury, with the PI3K/AKT pathway identified as a key mechanism mediating this regenerative effect [6]. Similarly, in cartilage and inflamed tissues, SOX9 helps maintain macrophage function and contributes to cartilage formation and tissue repair [1].

What role does SOX9 play in the balance between regeneration and fibrosis?

SOX9 appears to function as a "double-edged sword" in tissue repair, playing roles in both regenerative processes and pathological fibrosis. While SOX9 promotes regeneration in various contexts, its persistent activation can drive fibrotic processes in multiple organs including cardiac, liver, kidney, and pulmonary fibrosis [3]. In tracheal fibrosis models, SOX9 knockdown alleviates fibrosis by inhibiting granulation tissue proliferation, reducing inflammation and ECM deposition, and promoting apoptosis of granulation tissue. This fibrotic activity operates through the Wnt/β-catenin-SOX9 axis, with inhibition of SOX9 significantly reducing tracheal fibrosis after injury [7].

Experimental Protocols for SOX9 Research

Genetic Lineage Tracing of SOX9-Expressing Cells

Purpose: To track the fate and contribution of SOX9-expressing cells in development, homeostasis, and regeneration.

Detailed Methodology:

- Utilize Sox9CreER transgenic mice (available from Jackson Laboratory) crossed with appropriate reporter lines (e.g., RosatdTomato or RosaEYFP)

- Administer tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648-1G) via intraperitoneal injection at 0.08 mg/g body weight daily for three consecutive days to activate Cre recombinase

- Allow appropriate chase periods depending on research question (days to weeks)

- Induce tissue injury if studying regeneration (e.g., radiation injury using 16 Gy targeted thoracic radiation for lung injury models)

- Collect tissues at predetermined endpoints (e.g., 3, 7, 14, and 30 days post-injury)

- Process tissues for histological analysis, immunofluorescence, or flow cytometry to quantify SOX9-lineage cell contributions to regeneration [6]

SOX9 Knockdown in Fibrosis Models

Purpose: To investigate SOX9 function in fibrotic processes and evaluate its therapeutic potential.

Detailed Methodology:

- Establish tracheal fibrosis model in rats using tracheal brushing injury

- Implement SOX9 knockdown using siRNA or shRNA approaches

- Monitor fibrotic progression through histological analysis (H&E, Masson's trichrome staining)

- Assess expression of mesenchymal and ECM markers (collagen, α-SMA) via immunohistochemistry or Western blot

- Evaluate Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity by measuring β-catenin and p-GSK3β levels

- Quantify functional outcomes including granulation tissue area, epithelial regeneration, and apoptosis rates (TUNEL assay) [7]

Table 1: SOX9 Expression Across Biological Contexts

| Biological Context | SOX9 Expression Level | Functional Outcome | Key Regulatory Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Adenomas | Significantly upregulated | Impaired differentiation, cancer initiation | WNT/β-catenin [8] |

| Ovarian Cancer (Post-Chemo) | Consistently increased | Chemoresistance, stem-like state | Super-enhancer mediated epigenetic regulation [9] |

| Radiation-Induced Lung Injury | Elevated during repair | Tissue regeneration, stem cell activation | PI3K/AKT [6] |

| Tracheal Fibrosis | Markedly upregulated | ECM deposition, fibrosis progression | Wnt/β-catenin-SOX9 axis [7] |

| Normal Adult Lung | Sparse in bronchi, minimal in alveoli | Tissue homeostasis | Baseline maintenance [6] |

Troubleshooting Common SOX9 Research Challenges

Why might SOX9 inhibition produce conflicting results in different tissue repair models?

The conflicting effects of SOX9 inhibition stem from its context-dependent dual functions. In regenerative contexts like radiation-induced lung injury, SOX9 inhibition compromises repair, while in fibrotic diseases, it alleviates pathology. This dichotomy arises because SOX9 regulates both positive regenerative processes and pathological extracellular matrix deposition. Researchers should carefully consider the specific biological context, timing of intervention, and SOX9's differential interaction with signaling pathways (e.g., PI3K/AKT in regeneration vs. Wnt/β-catenin in fibrosis) when interpreting inhibition experiments [1] [6] [7].

How can researchers account for SOX9's complex regulation in experimental design?

SOX9 is regulated at multiple levels including transcriptionally, post-transcriptionally via miRNAs, and through extensive post-translational modifications. To comprehensively assess SOX9 activity, researchers should:

- Monitor both mRNA and protein levels, as discrepancies can indicate post-transcriptional regulation

- Analyze phosphorylation status (particularly S64 and S181) when investigating PKA-mediated regulation

- Consider using multiple detection methods (IHC, IF, Western) due to potential epitope masking from modifications

- Include controls for SOX9 dimerization state and partner transcription factors that significantly influence its activity [2]

What technical considerations are crucial for accurate SOX9 detection and quantification?

SOX9's nuclear localization and modification status present specific technical challenges. For immunohistochemistry, heat-induced epitope retrieval is essential, and antibody validation using SOX9-deficient controls is critical. For flow cytometry, nuclear extraction protocols may improve detection. When quantifying SOX9 in fibrosis models, IHC scoring should account for both intensity (0-3+) and percentage of positive cells, with the final score calculated as the product of these values [6]. Researchers should also be aware that SOX9 expression patterns can be highly compartmentalized, as seen in the intestinal crypt and tracheal epithelium.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SOX9 Studies

| Reagent/Catalog Number | Application | Key Features | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sox9CreER mice (JAX Stock) | Lineage tracing | Inducible Cre expression from Sox9 locus | Tamoxifen dose and timing critical for specific labeling [6] |

| Anti-SOX9 (Millipore AB5535) | IHC/IF | Well-validated for paraffin sections | Optimal at 1:200 dilution; requires antigen retrieval [6] |

| siRNA/SOX9 pools | Knockdown studies | Efficient SOX9 suppression | Validate efficiency and monitor off-target effects [7] |

| Perifosine (Beyotime SC0227) | Pathway inhibition | AKT inhibitor for PI3K/AKT studies | Use 250 mg/kg/week in mouse models [6] |

| SC79 (Beyotime SF2730) | Pathway activation | AKT pathway agonist | Use 5 mg/kg/week in mouse models [6] |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

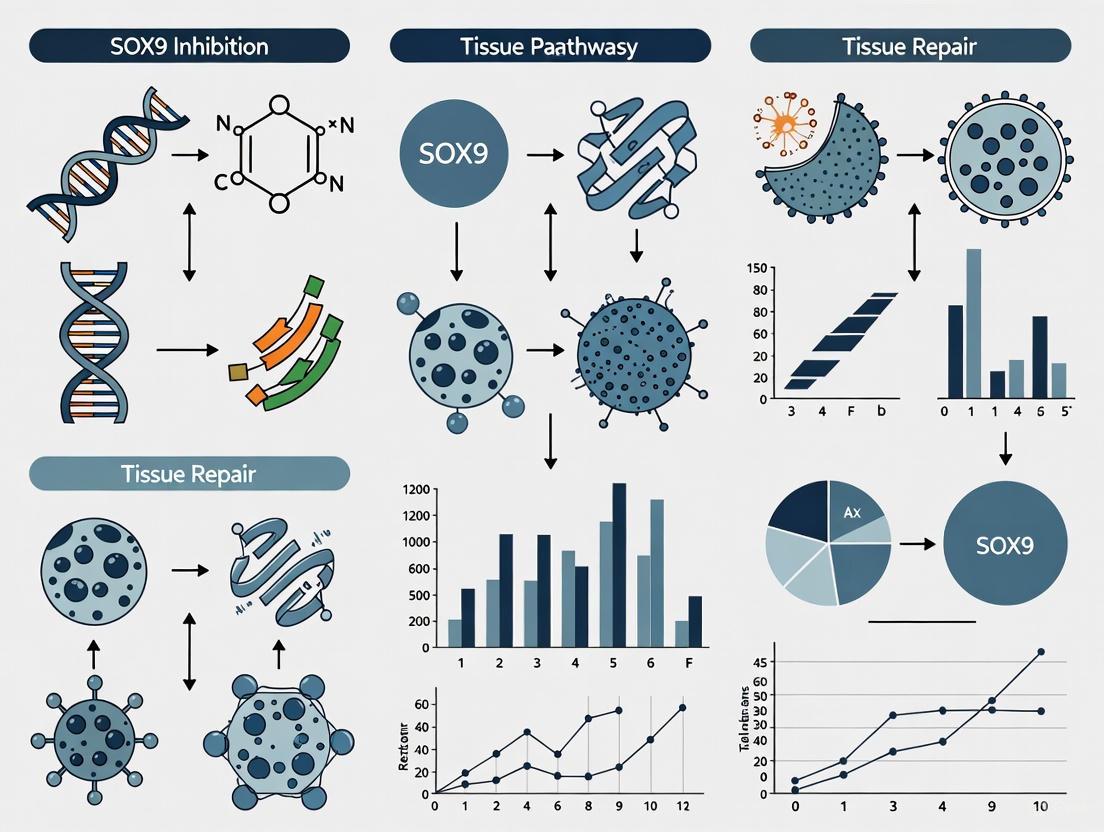

Figure 1: SOX9 in Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the positive feedback loop between SOX9 and Wnt signaling, showing how SOX9 both responds to and enhances pathway activity through GSK3β phosphorylation and β-catenin stabilization, ultimately driving proliferation and ECM gene expression in fibrosis and cancer contexts [8] [7].

Figure 2: SOX9 in PI3K/AKT-Mediated Regeneration. This diagram shows how SOX9-expressing cells activate the PI3K/AKT pathway to promote both proliferation and proper differentiation, ultimately driving tissue regeneration following injury as demonstrated in radiation-induced lung injury models [6].

Molecular Anatomy of the SOX9 Protein

SOX9 is a transcription factor characterized by several key functional domains that enable its diverse roles in cellular regulation. The protein structure includes a high-mobility group (HMG) box domain responsible for sequence-specific DNA binding, a dimerization domain (DIM), two transcriptional activation domains (TAM and TAC), and a proline/glutamine/alanine (PQA)-rich domain [1] [10]. The HMG domain facilitates DNA binding and induces significant bending by forming an L-shaped complex in the minor groove of DNA, while the transactivation domains interact with transcriptional co-activators to regulate gene expression [2] [10].

Regulatory Mechanisms: SOX9 undergoes extensive post-transcriptional modifications that influence its stability, localization, and activity. These include phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) which enhances DNA-binding affinity and promotes nuclear translocation, and SUMOylation which context-dependently either enhances or represses SOX9-dependent transcription [2]. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway also regulates SOX9 by degrading it in specific cellular contexts, while various microRNAs target SOX9 transcripts to control its expression [2].

Key Signaling Pathways Regulated by SOX9

SOX9 interacts with multiple critical signaling pathways to control cellular processes, with its functional outcomes depending on cellular context and binding partners.

Pathway-Specific Mechanisms: In the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, SOX9 directly interacts with β-catenin to inhibit its transcriptional activity during chondrocyte differentiation [2]. SOX9 also serves as a significant genetic target downstream of AKT signaling, where it promotes AKT-dependent tumor growth in triple-negative breast cancer by regulating SOX10 expression [11]. Through these interactions, SOX9 occupies a central position in coordinating multiple signaling outputs that determine cellular fate.

SOX9 in Cellular Proliferation and Cell Cycle Control

SOX9 exerts significant control over cellular proliferation through direct regulation of cell cycle progression and apoptotic pathways. In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells, SOX9 knockdown resulted in suppressed cell proliferation and colony formation, with apoptosis increased and the cell cycle arrested at the G0/G1 phase [12]. This demonstrates SOX9's critical role in maintaining continuous cell cycle progression.

Quantitative Effects of SOX9 Manipulation on Proliferation:

Table 1: SOX9 Knockdown Effects on Cancer Cell Proliferation

| Cell Type | Intervention | Proliferation Outcome | Cell Cycle Effects | Apoptosis Changes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNBC (MDA-MB-231) | SOX9 inhibition | Suppressed | G0/G1 phase arrest | Increased | [12] |

| TNBC (MDA-MB-436) | SOX9 inhibition | Suppressed | G0/G1 phase arrest | Increased | [12] |

| HGSOC | SOX9 knockout | Increased platinum sensitivity | Accelerated growth rate without chemotherapy | Not specified | [9] |

| Breast cancer (T47D) | SOX9 involvement | Antiproliferative | G0/G1 blockage | Not specified | [11] |

Molecular Mechanisms: SOX9 promotes proliferation through multiple mechanisms, including direct interaction with and activation of the polycomb group protein Bmi1 promoter, which suppresses the activity of the tumor suppressor InK4a/Arf sites [11]. SOX9 also collaborates with Slug (SNAI2) to encourage breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis, and serves as a target for miR-215-5p, where SOX9 overexpression can reverse the miR's inhibitory effects on BC cell growth [11].

SOX9-Mediated Regulation of Migration and Invasion

SOX9 significantly enhances cellular migration and invasion capabilities across multiple cancer types. In TNBC models, Transwell and wound-healing assays demonstrated that SOX9 inhibition markedly decreased the migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-436 cells [12]. This establishes SOX9 as a potent driver of metastatic behavior in aggressive cancers.

Migration and Invasion Mechanisms: SOX9 regulates the expression of motility-related genes and facilitates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. In colorectal cancer, the lncRNA MALAT1/miR-145/SOX9 axis plays a critical role in regulating cancer cell invasion and migration, with SOX9 upregulation promoting these aggressive behaviors [13]. SOX9 also interacts with various components of the tumor microenvironment, including cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor-associated macrophages, to create conditions favorable for invasion and metastasis [11].

SOX9 in Cell Survival and Death Decisions

SOX9 plays a complex role in determining cell fate, influencing decisions between survival, apoptosis, and chemoresistance. In TNBC models, SOX9-knockdown cells showed increased apoptosis, indicating that SOX9 normally functions to promote survival pathways [12]. Additionally, SOX9 expression induces significant resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) [9].

Chemoresistance Mechanisms: SOX9 drives chemoresistance through multiple pathways. It increases transcriptional divergence, reprogramming the transcriptional state of naive cells into a stem-like state that is more resistant to chemotherapy [9]. SOX9 expression is epigenetically upregulated following chemotherapy treatment, and this upregulation induces the formation of a stem-like subpopulation with significant chemoresistance capabilities in vivo [9]. In ovarian cancer, single-cell analysis revealed that chemotherapy treatment results in rapid population-level induction of SOX9 that enriches for this stem-like transcriptional state [9].

Table 2: SOX9 in Cancer Survival and Chemoresistance

| Cancer Type | Survival Function | Chemoresistance Role | Mechanism | Clinical Correlation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGSOC | Promotes cell survival | Drives platinum resistance | Transcriptional reprogramming to stem-like state | High SOX9 = shorter survival | [9] |

| Breast Cancer | Prevents apoptosis | Not specified | Regulation of apoptotic pathways | Not specified | [12] [11] |

| Multiple Cancers | Maintains stem cell populations | Confers multidrug resistance | Immune evasion, stress response | Poor prognosis | [1] [11] |

Experimental Protocols for SOX9 Research

SOX9 Knockdown Using Lentiviral Vectors

Protocol Objective: To achieve stable knockdown of SOX9 in cancer cell lines to study its functional roles.

Materials:

- Lentivirus vector pGCSIL-GFP (or similar)

- shRNA sequences targeting SOX9

- 293T cells for virus packaging

- Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent

- Target cells (e.g., MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-436)

Methodology:

- Design and clone SOX9-targeting shRNA sequences into lentivirus vector

- Example sequences: shSOX9-1: 5′-GCATCCTTCAATTTCTGTATA-3′; shSOX9-2: 5′-GCGGAGGAAGTCGGTGAAGAA-3′ [12]

- Co-transfect expression plasmid with helper plasmids into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000

- Harvest lentiviruses at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection

- Infect target cells using multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20

- Assess knockdown efficiency after 72 hours via RT-qPCR or Western blot

Validation Assays:

- Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay for proliferation

- Colony formation assay (14-day culture)

- Flow cytometry for cell cycle and apoptosis analysis

- Transwell and wound-healing assays for migration/invasion [12]

CRISPR-dCas9 System for SOX9 Activation

Protocol Objective: To precisely activate SOX9 expression without permanent genomic changes.

Materials:

- Lenti-dSpCas9-VP64 vector for CRISPR activation

- Lenti-EGFP-dual-gRNA vector for guide RNA expression

- SOX9-targeting sgRNAs

- Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) or other target cells

Methodology:

- Design sgRNAs targeting SOX9 promoter region

- Example: Sox9-1: GAGCTAGCCGTGATTGGCCCG; Sox9-2: CGGGTTGGGTGACGAGACAGG [14]

- Co-express dSpCas9-VP64 and sgRNAs in target cells

- Validate SOX9 upregulation via RT-qPCR and Western blot

- Assess functional outcomes: chondrogenic potential, gene expression changes

Applications: This system enables fine-tuning of SOX9 expression to desired levels, useful for studying its role in differentiation and disease models [14].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SOX9 Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Function/Application | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOX9 shRNAs | shSOX9-1, shSOX9-2, shSOX9-3 | Gene knockdown | Lentiviral-mediated SOX9 silencing [12] |

| CRISPR-dCas9 System | dSpCas9-VP64, SOX9 sgRNAs | Gene activation | Precise SOX9 upregulation [14] |

| Cell Viability Assay | Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) | Proliferation measurement | Quantifying cell growth after SOX9 manipulation [12] |

| Migration Assay | Transwell chambers | Migration/invasion assessment | Studying metastatic potential [12] |

| Colony Formation Assay | Giemsa staining | Clonogenic potential | Measuring long-term proliferation capacity [12] |

| Apoptosis Assay | Flow cytometry with Annexin V | Cell death quantification | Determining survival effects of SOX9 [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does SOX9 appear to have contradictory roles in different cancer types?

A1: SOX9 exhibits context-dependent functions based on cell type, signaling environment, and interacting partners. While typically oncogenic, it can display tumor-suppressive activity in specific contexts. This functional duality arises from SOX9's ability to interact with different partner transcription factors and recruit either co-activators or repressors depending on the cellular context [1] [2].

Q2: What are the most reliable methods for detecting SOX9 functional activity in cells?

A2: Combine multiple approaches: (1) Quantitative PCR and Western blot for expression levels; (2) Functional assays (CCK-8, colony formation) for proliferation; (3) Transwell and wound-healing for migration/invasion; (4) Flow cytometry for cell cycle and apoptosis analysis. Validation should include both gain-of-function and loss-of-function approaches [12] [9].

Q3: How does SOX9 contribute to chemoresistance, and can this be targeted therapeutically?

A3: SOX9 drives chemoresistance through multiple mechanisms: (1) Promoting a stem-like transcriptional state; (2) Increasing transcriptional plasticity; (3) Enhancing DNA damage repair pathways; (4) Activating survival signaling networks. Targeting SOX9 directly remains challenging, but upstream regulators (e.g., miRNAs) or downstream effectors may provide alternative therapeutic avenues [9] [11].

Q4: What considerations are important when studying SOX9 in tissue repair versus cancer contexts?

A4: Key considerations include: (1) SOX9 expression duration (transient in repair vs. sustained in cancer); (2) Cellular context (stem/progenitor cells in repair vs. transformed cells in cancer); (3) Microenvironment interactions; (4) Dose-dependent effects. In tissue repair, SOX9 promotes beneficial outcomes like cartilage maintenance, while in cancer these same proliferative and survival functions drive pathology [15] [14].

Technical Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Inconsistent SOX9 knockdown results across experiments.

- Potential Cause: shRNA off-target effects or inefficient viral transduction

- Solution: Use multiple distinct shRNAs to confirm phenotype specificity; optimize viral titer and transduction conditions; include rescue experiments with SOX9 cDNA resistant to shRNA targeting

Problem: Poor cell viability following SOX9 manipulation.

- Potential Cause: Excessive SOX9 suppression affecting essential cellular functions

- Solution: Titrate knockdown/knockout conditions; use inducible systems for temporal control; consider cell-type specific SOX9 dependencies

Problem: Discrepancy between SOX9 mRNA and protein expression measurements.

- Potential Cause: Post-transcriptional regulation or protein stability issues

- Solution: Implement protein degradation inhibitors if necessary; check for miRNA regulation; ensure antibody specificity in Western blots

Problem: Variable migration/invasion assay results with SOX9 modulation.

- Potential Cause: Microenvironmental factors or assay condition inconsistencies

- Solution: Standardize matrix composition in invasion assays; control for serum concentration in chemotaxis; use multiple complementary migration assays

FAQs: SOX9 in Intestinal Biology and Radiotherapy

Q1: What is the functional difference between SOX9-high and LGR5-high intestinal stem cells? SOX9-high cells represent a quiescent, radioresistant reserve intestinal stem cell (rISC) population, while LGR5-high cells represent active, proliferating intestinal stem cells (aISCs). Under homeostatic conditions, SOX9-high cells are slow-cycling and function as a reserve pool. Following injury, such as high-dose irradiation, these rISCs can convert into aISCs to drive epithelial regeneration. The loss of SOX9 function leads to the depletion of these label-retaining cells and dramatically increases intestinal sensitivity to radiation damage [16] [17].

Q2: Our research indicates that SOX9 inhibition could be a promising radiosensitization strategy for cancer. What is a critical consideration for this therapeutic approach? A critical consideration is the dual role of SOX9. While inhibiting SOX9 may sensitize tumor cells to radiation, it can simultaneously impair the regenerative capacity of healthy tissues. SOX9 is essential for maintaining reserve stem cells and promoting tissue repair in the intestinal epithelium. Therefore, a key research challenge is developing targeted inhibition strategies that affect cancerous tissue without compromising the intrinsic radioresistance and repair mechanisms of normal tissues, such as those in the intestine [16] [1] [17].

Q3: What are the primary molecular mechanisms by which SOX9 confers radioresistance? Evidence suggests that SOX9-dependent radioresistance is not primarily attributed to enhanced DNA repair or cell cycle arrest. Instead, research in mouse models indicates that SOX9 limits proliferation in reserve stem cells, maintaining them in a quiescent or slow-cycling state that is inherently more resistant to radiation-induced damage. The exact downstream pathways are under investigation, but this control of proliferative status is a key mechanism [16] [17].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methods for Investigating SOX9 Function

Protocol 1: Isolating and Characterizing Reserve Intestinal Stem Cells

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to demonstrate that SOX9-high cells are label-retaining, radioresistant rISCs [16] [17].

Label-Retention Assay (LRC Identification):

- Administration: Utilize transgenic mice (e.g., histone 2B-YFP) or implant subcutaneous osmotic minipumps to deliver nucleotide analogs like EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine) or BrdU over a sustained period (e.g., 7-14 days).

- Washout: Remove the pump or stop administration and allow a chase period of 8-12 days for the label to be diluted from rapidly dividing cells.

- Identification: Quiescent or slow-cycling rISCs will retain the label and can be identified as Label-Retaining Cells (LRCs) via immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.

Cell Sorting and Single-Cell Analysis:

- Mouse Models: Use reporter mice such as

Lgr5-EGFPandSox9-EGFP. - Tissue Processing: Dissociate jejunal crypts into single-cell suspensions.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Isulate distinct populations:

Lgr5(high)(aISCs) andSox9(high)(rISCs). - Single-Cell Gene Expression: Use an integrated microfluidics platform (e.g., Fluidigm C1 system) to perform quantitative PCR on single cells for a panel of genes, including aISC markers (

Lgr5,Ascl2), rISC markers (Bmi1,Hopx,Lrig1), and lineage differentiation markers.

- Mouse Models: Use reporter mice such as

Protocol 2: Lineage Tracing and Functional Regeneration Assay

This protocol tests the stem cell capacity and radioresistance of SOX9-expressing cells in vivo [16] [17].

Genetic Lineage Tracing:

- Mouse Model: Use

Sox9-CreERT2mice crossed with a reporter line (e.g.,ROSA26-loxP-STOP-loxP-tdTomato). - Induction: Administer tamoxifen (e.g., 2 mg intraperitoneally) to activate Cre recombinase and indelibly label SOX9-expressing cells and their progeny with tdTomato.

- Analysis: Track the lineage over time to assess multipotency and contribution to epithelial regeneration.

- Mouse Model: Use

Radiation Injury Model:

- Treatment: Expose

SOX9knockout mice and control littermates to a high dose of irradiation (e.g., 12-14 Gy). - Assessment:

- Crypt Survival: Quantify the number of regenerating crypts per intestinal circumference 3-5 days post-irradiation.

- Cell Death: Analyze apoptosis levels (e.g., by TUNEL staining) shortly after irradiation.

- Proliferation: Assess cell cycle re-entry and proliferation during the regenerative phase (e.g., by EdU pulse or Ki-67 staining).

- Treatment: Expose

Table 1: Key Findings from SOX9 Knockout Studies in Mouse Intestine

| Experimental Readout | Observation in SOX9-KO vs. Control | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|

| Label-Retaining Cells (LRCs) | Significantly lost or reduced [16] [17] | Inducible SOX9 knockout mice |

| Crypt Regeneration Post-Irradiation | Severely impaired [16] [17] | Conditional SOX9 knockout mice after high-dose irradiation |

| Radiation Sensitivity | Markedly increased [16] [17] | Crypt survival assay in SOX9 knockout mice |

| Proliferation in LRCs | Dysregulated / Increased [16] | EdU/Ki-67 staining in label-retaining, SOX9-high cells |

| Single-Cell Marker Co-expression | A subset of crypt-based Sox9(high) cells co-express Lgr5, Bmi1, Lrig1, and Hopx [16] |

FACS-isolated Sox9(high) cells from reporter mice |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SOX9 Functional Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

Sox9-EGFP Reporter Mouse |

Enables identification and fluorescence-activated cell sorting of SOX9-expressing cells [16] | Isolating pure populations of Sox9(high) and Sox9(low) intestinal epithelial cells for transcriptomic analysis. |

Sox9-CreERT2 Mouse Line |

Allows for inducible, lineage-specific genetic manipulation or lineage tracing of SOX9-expressing cells [16] [17] | Tracing the fate of SOX9+ cells during homeostasis or after injury via tamoxifen-induced activation. |

Conditional Sox9 Allele (Sox9fl/fl) |

Enables tissue-specific or inducible knockout of SOX9 when crossed with appropriate Cre drivers [16] [18] | Generating intestinal-epithelial specific SOX9 knockout mice (Sox9fl/fl;VillinCre or VillinCreERT2) to study gene function. |

Lgr5-EGFP Reporter Mouse |

Serves as a benchmark for identifying active intestinal stem cells (aISCs) for comparative studies [16] | Directly comparing gene expression profiles and functional properties of Sox9(high) rISCs versus Lgr5(high) aISCs. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Figure 1: SOX9 Regulation and Function in Reserve Intestinal Stem Cells. SOX9 expression is activated by the Wnt/β-catenin/TCF4 pathway. It maintains a quiescent, slow-cycling state in reserve ISCs, limiting proliferation and conferring radioresistance. Upon radiation injury, these SOX9-high rISCs can convert to an active state to drive epithelial regeneration [16] [19] [17].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing SOX9 Function. A typical integrated approach to study SOX9, combining cell sorting and omics analysis with in vivo lineage tracing and functional knockout models to define its role in stem cell biology and radioresistance [16] [17].

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

SOX9 Knockdown Efficiency Issues

Problem: Inconsistent SOX9 knockdown in human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (HUC-MSCs) using lentiviral vectors.

Solution:

- Verify Viral Titer: Confirm lentivirus concentration exceeds 1x10^8 TU/mL before transduction.

- Optimize MOI: Perform multiplicity of infection (MOI) gradient test (e.g., MOI 10-50) using scramble shRNA control.

- Selection Pressure: Apply 1 μg/mL puromycin selection for 15 days with doxycycline induction (80 μg/mL) for shRNA expression [20].

- Validation: Always confirm knockdown via qRT-PCR and Western blot before functional assays.

Prevention: Use fresh viral aliquots; maintain consistent cell passage numbers (P3-P4); include positive and negative controls in all experiments.

Poor HUC-MSC Migration in Transwell Assays

Problem: Reduced migratory capacity of SOX9-deficient HUC-MSCs in Transwell migration assays.

Solution:

- Cell Preparation: Use low-glucose DMEM with 10% FBS; ensure cell viability >95% before assay.

- Proper Seeding: Seed 1×10^5 cells/well in top chamber with 8-μm pores; serum-starve for 4-6 hours prior to assay.

- Fixation & Staining: Fix migrated cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes; stain with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 minutes [20].

- Quantification: Count cells in six random visual fields under 100x magnification.

Troubleshooting: Check FBS concentration in lower chamber as chemoattractant (5-10%); verify pore size not clogged; ensure consistent incubation time (typically 6-24 hours).

Inconsistent In Vivo Burn Healing Results

Problem: Variable repair outcomes in rat burn models with SOX9-modified HUC-MSCs.

Solution:

- Standardize Burn Model: Use consistent deep second-degree burn creation method; control for burn depth histologically.

- Cell Delivery: Apply 1-2x10^6 HUC-MSCs per burn site in PBS buffer; use consistent delivery method (topical vs. injection).

- Timing: Begin treatment within 2 hours post-burn for optimal effect [20].

- Control Groups: Include shSOX9-transfected HUC-MSCs, sh-control transfected HUC-MSCs, and PBS-only groups.

Monitoring: Assess healing daily; measure wound contraction; collect tissue samples at multiple time points for histological analysis of Ki67, CK14, and CK18 expression [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the molecular rationale for targeting SOX9 in burn wound healing?

A1: SOX9 serves as a master regulator of mesenchymal stem cell function. Knockdown studies demonstrate that SOX9 depletion inhibits HUC-MSC proliferation and migration, reduces expression of critical cytokines (IL-6, IL-8), growth factors (GM-CSF, VEGF), and stemness-related genes (OCT4, SALL4). This directly impairs burn repair capacity and accessory structure regeneration (hair follicles, glands) [20].

Q2: How does SOX9 influence cutaneous regeneration versus fibrosis?

A2: SOX9 exhibits dual functionality. In physiological regeneration, SOX9 promotes proper tissue patterning and accessory structure formation. However, in pathological contexts, SOX9 drives endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), contributing to excessive fibrosis and scarring. Conditional knockout of Sox9 in murine endothelium significantly reduces pathological EndMT and scar area [21].

Q3: What are the key downstream effectors of SOX9 in wound healing?

A3: Key downstream mediators include:

- Cytokines/Growth Factors: IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, VEGF

- Stemness Markers: OCT4, SALL4

- Proliferation Markers: Ki67

- Differentiation Markers: CK14, CK18 for epithelial lineages [20]

Q4: Which signaling pathways interact with SOX9 during tissue repair?

A4: SOX9 interacts with multiple pathways:

- Wnt/β-catenin: HUC-MSC exosomes activate β-catenin signaling via Wnt4 [20]

- Notch Pathway: Antagonistic relationship with Rbpj; Rbpj deletion enhances Sox9 and EndMT [21]

- Hedgehog Signaling: Upregulates Sox9 expression in pathological EndMT [21]

- NF-κB Pathway: Positively regulates SOX9 expression in chondrogenesis [22]

Q5: What experimental models are best for studying SOX9 in burn repair?

A5: Optimal models include:

- In Vitro: HUC-MSCs with lentiviral SOX9 knockdown for migration/proliferation studies [20]

- In Vivo: Rat deep second-degree burn models with HUC-MSC transplantation [20]

- Genetic Models: Endothelial-specific Sox9 knockout mice (Sox9fl/fl/Cdh5-CreER) for fibrosis analysis [21]

- Therapeutic Testing: Topical siRNA against Sox9 in murine wound models [21]

Table 1: Functional Consequences of SOX9 Knockdown in HUC-MSCs

| Parameter | Effect of SOX9 KD | Experimental Method | Magnitude of Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | Decreased | CCK-8 assay & cell counting | Significant reduction at 24-48h [20] |

| Migration | Impaired | Transwell assay | ~60% reduction vs. control [20] |

| IL-6/IL-8 | Reduced expression | qRT-PCR | Significant downregulation [20] |

| GM-CSF/VEGF | Reduced expression | qRT-PCR | Significant downregulation [20] |

| OCT4/SALL4 | Reduced expression | qRT-PCR | Significant downregulation [20] |

| In Vivo Repair | Impaired | Rat burn model | Poor accessory structure regeneration [20] |

Table 2: SOX9 in Different Experimental Models of Tissue Repair

| Model System | SOX9 Role | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HUC-MSCs + Burn | Pro-repair | Enhances proliferation, migration, cytokine secretion | [20] |

| Endothelial Sox9 KO | Anti-fibrotic | Reduces EndMT and scar area | [21] |

| BMSCs + Nicotine | Chondrogenic | Histone hypo-acetylation suppresses SOX9-mediated repair | [23] |

| Topical Sox9 siRNA | Anti-fibrotic | Blocks pathological EndMT, reduces scarring | [21] |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SOX9 Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Product/Example | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | HUC-MSCs | Primary cell model for repair studies | Isolate from umbilical cord; use P3-P4; culture in low-glucose DMEM + 10% FBS [20] |

| Knockdown System | Lentiviral shSOX9 | SOX9 inhibition | pGPH1/Neo vector; puromycin selection (1 μg/mL, 15 days); doxycycline induction (80 μg/mL) [20] |

| In Vivo Model | Rat burn model | Therapeutic testing | Deep second-degree burns; monitor accessory structure regeneration [20] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-Ki67, Anti-CK14, Anti-CK18 | Histological assessment | Evaluate proliferation and differentiation in regenerated tissue [20] |

| SOX9 Inhibitor | Sox9 siRNA | Therapeutic intervention | Topical application reduces scar area by blocking EndMT [21] |

| Analysis Method | qRT-PCR primers for SOX9 targets | Molecular profiling | IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, VEGF, OCT4, SALL4 [20] |

Core Concepts: SOX9 in Tissue Homeostasis and Disease

What is the primary function of SOX9 in cartilage, and why is it a target for therapeutic inhibition? SOX9 (SRY-related high-mobility group box gene 9) is a pivotal transcription factor for chondrocyte function. It acts as a master regulator of chondrogenesis by transactivating essential cartilage-specific genes, such as those for type II collagen, and is mandatory for proper cartilage development and repair [24]. In the context of therapeutic inhibition, SOX9 is often targeted in oncology because it is frequently overexpressed in various solid cancers, where it promotes tumor proliferation, metastasis, chemoresistance, and the maintenance of cancer stem-like cells (CSCs). Inhibiting SOX9 is seen as a strategy to eradicate CSCs and sensitize tumors to treatments like radiotherapy [25] [1].

What role does SOX9 play in the vasculature, particularly in smooth muscle and endothelial cells? SOX9 plays a complex and context-dependent role in the vasculature. In Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs), SOX9 drives a phenotypic transformation from a contractile to a synthetic, proliferative state. This transition is a key event in pathologies like in-stent restenosis and vascular aging, where SOX9 promotes neointimal hyperplasia and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [26] [27]. In Endothelial Cells, SOX9 has been identified as an early transcriptional driver of Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EndMT). In conditions like atherosclerosis, exposure to oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) upregulates SOX9, leading to a loss of endothelial identity and a gain of mesenchymal characteristics in endothelial progenitor cells [28].

What is the central thesis regarding the side effects of SOX9 inhibition on tissue repair? The central thesis is that while SOX9 inhibition holds therapeutic promise, particularly in oncology, it poses a significant risk of impairing vital tissue repair mechanisms. This is because SOX9 is a critical promoter of chondrogenesis for cartilage repair and a regulator of stem/progenitor cell function. Therefore, systemic inhibition of SOX9 may lead to unintended consequences, such as weak cartilage regeneration and impaired healing of endothelial and other tissues, by disrupting these essential physiological processes [23] [25] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Investigating SOX9 Biology and Inhibition

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA/shSOX9 | Knockdown of SOX9 expression to study loss-of-function phenotypes. | Silencing SOX9 reversed oxLDL-induced EndMT in ECFCs and attenuated neointimal hyperplasia in a rat carotid injury model [28] [27]. |

| Sox9fl-fl / Cdh5CreERt2 Mice | Endothelial-specific, inducible knockout of Sox9 for in vivo lineage tracing and functional studies. | Used to demonstrate that endothelial-specific Sox9 knockout abrogates EndMT in a high-fat diet murine model [28]. |

| α7-nAChR Inhibitor (MLA) | Pharmacological inhibitor used to dissect specific signaling pathways upstream of SOX9. | Methyllycaconitine (MLA) was used to verify that nicotine suppresses SOX9 and chondrogenesis via the α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor [23]. |

| Oxidized LDL (oxLDL) | Inducer of EndMT and SOX9 expression in endothelial cell models. | Treatment of ECFCs with oxLDL (12.5-50 µg/mL) induced SOX9 expression and triggered EndMT [28]. |

| Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB (PDGF-BB) | Inducer of VSMC phenotypic transformation and proliferation. | Used in vitro to stimulate SOX9 expression and nuclear translocation in primary VSMCs, driving their proliferation and migration [27]. |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay | Used to validate direct transcriptional regulation by SOX9 on target gene promoters. | Identified that SOX9 directly binds to the STAT3 promoter to enhance its activity in VSMCs [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: SOX9 Inhibition in Tissue Repair Research

FAQ 1: We are investigating SOX9 inhibition to sensitize gastrointestinal cancers to radiotherapy, but observe severe toxicity in intestinal models. What could be the mechanism? This is a predicted, on-target side effect. SOX9 is crucial for the function of reserve intestinal stem cells (rISCs), which are responsible for epithelial regeneration and are relatively radioresistant. When SOX9 is inhibited, these rISCs lose their regenerative capacity and undergo apoptosis following radiation exposure, leading to the observed enteritis [25]. Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Confirm On-Target Effect: Use a SOX9 reporter cell line or qPCR to verify that your inhibitor effectively reduces SOX9 transcriptional activity in your intestinal organoid model.

- Assess Functional Regeneration: Perform a crypt regeneration assay ex vivo. Compare the formation of new organoids from single intestinal crypts treated with your SOX9 inhibitor versus control after a sub-lethal dose of radiation (e.g., 8-10 Gy).

- Mitigation Strategy: Consider a localized or targeted delivery system for the SOX9 inhibitor (e.g., nanoparticle-conjugated inhibitors) to minimize exposure to healthy intestinal tissue. Alternatively, explore the temporal administration of SOX9 inducers post-radiation to boost crypt repair [25].

FAQ 2: Our in vivo cartilage repair study shows that a potential therapeutic agent worsens healing. We suspect it inadvertently suppresses SOX9. How can we confirm this and identify the upstream pathway? This mirrors findings where nicotine was shown to weaken cartilage repair by suppressing SOX9. Your investigation should focus on the SOX9 promoter's epigenetic status and its key upstream regulators [23]. Troubleshooting Protocol:

- In Vivo Confirmation: Re-generate your cartilage defect model (e.g., in rat) and administer the therapeutic agent. Perform immunohistochemistry on the regenerated tissue for SOX9 protein levels and key chondrogenic markers (e.g., type II collagen). A concomitant decrease would support your hypothesis.

- In Vitro Mechanism Analysis:

- Model: Use Bone Marrow-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs) induced to chondrogenically differentiate.

- Treatment: Apply your therapeutic agent at relevant concentrations.

- Upstream Analysis: Measure intracellular Ca2+ levels (e.g., with Fluo-4 AM dye) and calcineurin (CaN) activity using a commercial assay kit. The nicotine study found this pathway activates NFATc2, which suppresses SOX9 [23].

- Epigenetic Analysis: Perform Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with antibodies against NFATc2 and acetylated histones (H3K9ac, H3K14ac) on the SOX9 promoter. A successful pathway inhibition would show increased NFATc2 binding and decreased histone acetylation at the SOX9 promoter.

- Rescue Experiment: Co-treat cells with your agent and a selective inhibitor of the identified upstream pathway (e.g., a calcineurin inhibitor like Cyclosporine A) to see if chondrogenic differentiation can be restored.

FAQ 3: In our model of atherosclerosis, SOX9 inhibition successfully blocks EndMT but also unexpectedly impairs endothelial progenitor self-renewal. Why does this happen? This occurs because SOX9 has distinct, separable functions in the same cell type. In endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs), SOX9 activation drives the transcriptional reprogramming of EndMT. However, its basal expression is also involved in regulating the self-renewal capacity of these vessel-resident progenitors. Ablating SOX9 therefore disrupts both pathological transition and essential progenitor maintenance [28]. Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Phenotypic Separation: Use RNA-sequencing and ATAC-sequencing on your SOX9-knockdown ECFCs. Analyze the data to identify gene clusters and chromatin regions specifically associated with the EndMT program (e.g., loss of CD31, gain of α-SMA) versus those governing self-renewal (e.g., cell cycle regulators).

- Functional Assays: Conduct a single-cell colony formation (self-renewal) assay. Compare the ability of control, SOX9-knockdown, and SOX9-overexpressing ECFCs to form high-proliferative potential colonies. This will quantitatively confirm the self-renewal defect.

- Alternative Strategy: Instead of global SOX9 knockout, aim to therapeutically target the specific co-factors or downstream genes that SOX9 recruits to drive EndMT, while sparing its other regulatory functions. The data from Step 1 will be critical for identifying these specific targets.

Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Protocol 1: Evaluating the Impact of a Compound on SOX9-Mediated Cartilage Repair

This protocol is based on the methodology used to investigate nicotine's effect on SOX9 in cartilage repair [23].

Workflow:

Detailed Steps:

- In Vivo Cartilage Repair Model:

- Create full-thickness cartilage defects in the femoral condyles of rats.

- Transplant BMSCs into the defect site.

- Administer your test compound systemically (e.g., via osmotic minipump) at a clinically relevant dose for a duration sufficient for repair (e.g., 12 weeks). Include vehicle control and untreated groups.

- Analysis: Harvest the repaired tissue. Perform histological scoring (e.g., ICRS score) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for SOX9 and type II collagen to quantitatively assess repair quality and SOX9 expression.

- In Vitro Chondrogenic Differentiation:

- Isolate and culture BMSCs.

- Induce chondrogenic differentiation in pellet or micromass culture.

- Treat with a dose range of your compound (e.g., 0.1 to 100 µM). Include a positive control for SOX9 suppression (e.g., 10 µM nicotine) and a negative control (vehicle).

- Rescue Experiments: Co-treat with pathway-specific inhibitors, such as Methyllycaconitine (MLA, 10 µM) for α7-nAChR or siRNA against NFATc2.

- Outcome Measures:

- Chondrogenesis: Alcian blue or Safranin O staining for proteoglycans; qPCR for SOX9, COL2A1, ACAN.

- Upstream Signaling: Measure intracellular Ca2+ with fluorescent dyes (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) and calcineurin activity with a colorimetric assay kit.

- Epigenetics: Perform ChIP-qPCR on the SOX9 promoter region using antibodies against acetylated H3K9 and H3K14.

Protocol 2: Dissecting SOX9's Role in Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EndMT)

This protocol is adapted from studies on oxLDL-induced EndMT in endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) [28] [29].

Workflow:

Detailed Steps:

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Isolate and culture human ECFCs from cord blood or placenta on collagen-coated flasks in EGM-2 medium.

- Induce EndMT by treating ECFCs with oxLDL (25-50 µg/mL) for 5 days, refreshing media every 2-3 days.

- Genetic Manipulation:

- Transduce ECFCs with lentivirus carrying either shRNA targeting SOX9 (shSOX9) or a SOX9 overexpression (SOX9 OE) construct. Include scrambled shRNA (shSCR) and empty vector controls.

- Select stable pools with puromycin (1 µg/mL for 5 days).

- Phenotypic Characterization:

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze the expression of endothelial (CD31, CD34) and mesenchymal (CD90, α-SMA) surface markers.

- Functional Assays:

- Capillary Formation: Seed cells on Matrigel and quantify tube network formation after 48 hours.

- Migration: Perform a scratch/wound healing assay and measure closure percentage over 24-48 hours.

- Contractility: Use a collagen contraction assay and measure gel area reduction over 72 hours.

- Self-Renewal Assay: This is critical for detecting side effects. FACS-sort single ECFCs into collagen-coated wells. Culture for 14 days, then count and classify colonies based on size: High Proliferative Potential (>500 cells), Low Proliferative Potential (>250 cells), and endothelial clusters (>50 cells).

- Molecular Analysis:

- RNA-seq/ATAC-seq: Perform these assays on control and SOX9-manipulated ECFCs to identify global transcriptional and chromatin accessibility changes driven by SOX9 during EndMT.

Supporting Data & Pathway Diagrams

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of SOX9 Manipulation in Different Tissue Contexts

| Tissue/Cell Type | Intervention | Key Quantitative Outcome | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cartilage (in vivo rat model) [23] | Nicotine (2 mg/kg/d) | Suppressed SOX9 expression; impaired cartilage repair score. | Nicotine exposure compromises cartilage regeneration via SOX9 downregulation. |

| ECFCs (Endothelial Progenitors) [28] | oxLDL (50 µg/mL) | 3.2-fold reduction in CD34+ cells; 2.2% of cells gained CD90 expression. | oxLDL induces a full EndMT phenotype in progenitor cells. |

| ECFCs (Endothelial Progenitors) [28] | shSOX9 + oxLDL | Reversal of oxLDL-induced EndMT marker shift and morphology. | SOX9 is necessary for executing the oxLDL-induced EndMT program. |

| VSMCs (in vitro) [27] | PDGF-BB + shSOX9 | Suppressed VSMC proliferation and migration. | SOX9 is a critical mediator of VSMC phenotypic transformation. |

| Intestinal Stem Cells [25] | SOX9 knockout + Radiation | Loss of crypt regeneration; increased apoptosis. | SOX9 is essential for the radioresistance and regenerative capacity of reserve intestinal stem cells. |

Integrated Pathway Diagram: SOX9 in Tissue Integrity and Disease This diagram synthesizes the key signaling pathways involving SOX9 in cartilage, vasculature, and stem cells, illustrating both its physiological roles and the potential side effects of its inhibition.

FAQs: Navigating the SOX9 Dual-Role Dilemma in Research

FAQ 1: How can the same transcription factor, SOX9, drive both tissue repair and cancer progression?

SOX9's functional paradox is rooted in context-dependent regulation. Its activity is determined by the cellular niche, its binding partners, and post-translational modifications [30] [2]. In healthy tissue, SOX9 activation is a transient, tightly regulated process essential for regeneration. However, in cancer, this regulation is lost, leading to sustained, constitutive SOX9 expression that drives tumorigenesis and stemness [4]. A key study in kidney injury showed that the fate of a tissue microenvironment—towards scarless repair (SOX9on-off) or fibrosis (SOX9on-on)—depends on the precise dynamics of SOX9 activity [31].

FAQ 2: What are the primary risks of systemic SOX9 inhibition for cancer therapy?

The main risk is the impairment of normal tissue regeneration and repair, particularly in tissues reliant on SOX9-positive stem and progenitor cells. For instance, SOX9 is crucial for the function of reserve intestinal stem cells (rISCs), which are essential for epithelial regeneration following injury, such as radiation exposure [25]. Inhibiting SOX9 could ablate this radioresistant cell population, leading to severe complications like enteritis. Similarly, in osteoarthritis, SOX9 is vital for chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage maintenance [14] [22].

FAQ 3: Which signaling pathways upstream of SOX9 should we monitor in our models?

Your experimental models should closely monitor the key signaling pathways that regulate SOX9 expression and activity. The following table summarizes the major regulators.

| Signaling Pathway | Effect on SOX9 | Relevant Biological Context |

|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Upregulation & Interaction [30] [32] [2] | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Intestinal Stem Cells |

| NF-κB | Direct transcriptional upregulation [22] [25] | Inflammation, Chondrogenesis, Pancreatic Cancer |

| TGFβ/Smad | Activation [32] | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| Hedgehog (Hh) | Upregulation [30] [2] | Chondrogenesis, Liver Fibrosis |

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for detecting meaningful changes in SOX9 activity in vivo?

Beyond measuring mRNA and total protein levels, employ these functional and spatial assessments:

- Assess Functional Output: Monitor well-established downstream targets, such as Osteopontin (OPN) in HCC [32] or Collagen type II (Col2a1) in chondrogenesis [2].

- Perform Temporal Analysis: SOX9's role is defined by its kinetics. Use time-course experiments to distinguish between transient (regenerative) and sustained (oncogenic) expression [31] [4].

- Implement Spatial Context: Use techniques like immunofluorescence or in situ hybridization to determine if SOX9 is expressed in the correct stem/progenitor cell niche and not in aberrant locations [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Differentiating SOX9's Pro-Regenerative vs. Pro-Oncogenic Functions

Challenge: In an in vivo model, it is difficult to determine whether SOX9 expression is contributing to wound healing or promoting pre-malignant changes.

Solution: Implement a multi-parameter assessment strategy to classify the SOX9-positive cell population.

Solution A: Molecular Phenotyping

- Action: Co-stain for SOX9 with markers of cell fate and proliferation.

- Rationale: Regenerative SOX9 is often associated with differentiation markers (e.g., Col2a1 in cartilage), while oncogenic SOX9 is linked to sustained proliferation markers (e.g., Ki-67) and stemness genes (e.g., Nanog) [32] [4].

Solution B: Temporal Tracking

- Action: Measure SOX9 levels at multiple time points after injury (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14).

- Rationale: A peak and subsequent decline in SOX9 suggest a regenerative response. Persistent elevation beyond the normal healing window suggests a potential pathological switch towards a pro-oncogenic state [31] [4].

Problem 2: Overcoming SOX9-Mediated Therapy Resistance

Challenge: Cancer stem cells (CSCs) with high SOX9 expression demonstrate resistance to chemotherapy and radiation [30] [32] [33].

Solution: Target the mechanisms that stabilize SOX9 protein or its downstream effectors.

Solution A: Disrupt SOX9 Protein Stability

- Action: Investigate the inhibition of deubiquitinating enzymes like USP28, which stabilizes SOX9 by preventing its FBXW7-mediated degradation [33].

- Protocol Note: The USP28-specific inhibitor AZ1 has been shown to promote SOX9 degradation and sensitize ovarian cancer cells to PARP inhibitors [33]. Consider co-treatment strategies.

Solution B: Modulate Downstream Pathways

- Action: In SOX9-high cancers, target downstream effector pathways like Wnt/β-catenin [32].

- Rationale: SOX9 regulates key resistance pathways; simultaneous inhibition may overcome inherent treatment resistance.

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Evidence of SOX9's Dual Role

Table 1: SOX9 in Human Cancers - Correlation with Poor Prognosis [30]

| Cancer Type | SOX9 Status | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Overexpression | Poor overall survival, Poor disease-free survival |

| Breast Cancer | Overexpression | Promotes metastasis, Poor overall survival |

| Prostate Cancer | Overexpression | High clinical stage, Poor relapse-free survival |

| Colorectal Cancer | Overexpression | Promotes cell proliferation, senescence inhibition, chemoresistance |

Table 2: SOX9 in Regeneration & Tissue Repair

| Experimental Context | SOX9 Function | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney Injury [31] | Fate Switch | SOX9on-on state linked to fibrosis; SOX9on-off state linked to scarless repair. |

| Intestinal Regeneration [25] | Stem Cell Maintenance | SOX9 knockout reserve intestinal stem cells impaired regeneration after radiation. |

| Osteoarthritis Therapy [14] | Chondrogenesis | CRISPRa-mediated Sox9 activation in MSCs enhanced cartilage repair in a mouse model. |

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-dCas9 for Modulating SOX9 and NF-κB in MSC Therapy

This protocol is adapted from a study enhancing mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) therapy for osteoarthritis [14].

1. Objective: To simultaneously activate SOX9 and inhibit RelA (a key NF-κB subunit) in human MSCs to enhance chondrogenic potential and immunomodulatory properties.

2. Materials:

- Lentiviral Vectors:

- Lenti-dSpCas9-VP64 (for transcriptional activation, CRISPRa)

- Lenti-dSaCas9-KRAB (for transcriptional repression, CRISPRi)

- Lenti-EGFP-dual-gRNA vector (to express two guide RNAs)

- Validated sgRNA Sequences [14]:

- For Sox9 activation: Sox9-2:

CGGGTTGGGTGACGAGACAGG; Sox9-3:ACTTACACACTCGGACGTCCC - For RelA inhibition: RelA-1:

CCGAAATCCCCTAAAAACAGA; RelA-3:TGCTCCCGCGGAGGCCAGTGA

- For Sox9 activation: Sox9-2:

- Cell Culture Media: Standard MSC growth medium and chondrogenic differentiation medium.

3. Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Culture primary human bone marrow-derived MSCs (CD45⁻ population) in standard growth medium.

- Virus Production & Transduction: Package the lentiviral constructs in HEK293T cells. Co-transduce MSCs with the three vectors (dSpCas9-VP64, dSaCas9-KRAB, and the dual-gRNA vector).

- Cell Selection: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate EGFP-positive cells successfully transduced with the gRNA vector.

- Validation:

- qRT-PCR & Western Blot: Confirm SOX9 upregulation and RelA downregulation.

- In Vitro Chondrogenesis: Pellet transduced MSCs in chondrogenic differentiation medium for 21 days. Analyze via safranin O staining (proteoglycans) and immunostaining for collagen type II.

- In Vivo Application: In a surgical mouse model of OA, administer intra-articular injections of the modified MSCs and monitor cartilage degradation and pain relief compared to control groups.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SOX9 Functional Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems (VP64/KRAB) | Precise transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) or interference (CRISPRi) of SOX9. | Enhancing chondrogenic potential of MSCs by fine-tuning SOX9 levels [14]. |

| SOX9 Reporter Vector (e.g., SOX9-EGFP) | FACS-based isolation of SOX9-positive and negative cell populations. | Isolating SOX9+ cancer stem cells from hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines for functional assays [32]. |

| USP28 Inhibitor (e.g., AZ1) | Promotes ubiquitin-mediated degradation of SOX9 protein. | Re-sensitizing ovarian cancer cells to PARP inhibitors by reducing SOX9 stability [33]. |

| OPN (Osteopontin) Measurement | Acts as a surrogate, serum-based marker for SOX9+ CSCs. | Correlating SOX9 activity in HCC tumors with a measurable biomarker in patient blood [32]. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Approaches to SOX9 Inhibition and Assessment of Repair Impairment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary considerations when choosing between shRNA knockdown and CRISPR-i for inhibiting SOX9 in tissue repair models? The choice depends on the required duration of suppression, the need for reversibility, and potential off-target effects. shRNA knocks down gene expression at the mRNA level, leading to a transient, reversible suppression that is suitable for studying acute effects or essential genes where a complete knockout would be lethal [34]. CRISPR-i, which inhibits transcription at the DNA level, can offer higher specificity and fewer off-targets, but its effect can be more persistent [34]. For SOX9, which has a dual role in promoting cancer stemness but also in tissue regeneration, a reversible system like shRNA might be preferable for initial functional studies to avoid irreversible damage to repair mechanisms [25] [1].

FAQ 2: We are observing inconsistent SOX9 knockdown efficiency with our shRNA constructs. What could be the cause? Inconsistent shRNA efficiency can stem from several factors:

- Off-target effects: shRNA is notorious for sequence-dependent off-target effects. Re-design the shRNA sequence using updated algorithms and validate with multiple constructs targeting different regions of the SOX9 transcript [34].

- Delivery and expression: Ensure your viral delivery system (lentivirus/retrovirus) has high titer and transduction efficiency. Check the promoter in your shRNA vector (e.g., U6 or H1) for proper activity in your specific cell type.

- SOX9 protein stability: The SOX9 protein may have a long half-life. Even with successful mRNA knockdown, protein levels may persist. Allow sufficient time (e.g., 72-96 hours) post-transduction before assessing knockdown and monitor both mRNA (by qRT-PCR) and protein (by immunoblotting) levels.

FAQ 3: Could the inhibition of SOX9 during our in vivo experiments inadvertently worsen tissue damage? Yes, this is a critical risk. SOX9 is essential for the function of reserve intestinal stem cells (rISCs) and their capacity for epithelial regeneration following injury, such as from radiation [25]. In cartilage and other tissues, SOX9 helps maintain macrophage function and contributes to tissue repair [1]. Therefore, inhibiting SOX9, while potentially therapeutic for cancer, may impair tissue repair mechanisms. It is crucial to include detailed histological analysis and functional regeneration assays in your animal models to monitor these potential side effects.

FAQ 4: What is a key advantage of using small-molecule inhibitors for SOX9 in a drug discovery context? A significant advantage is the ability to achieve temporal and dose-dependent control. Unlike genetic tools that permanently or semi-permanently alter gene expression, small-molecule inhibitors can be administered at specific times and in titratable concentrations. This allows researchers to precisely interrogate the effects of acute versus chronic SOX9 inhibition and to potentially dissect its different roles in various biological processes [25].

FAQ 5: How can we improve the therapeutic window when targeting SOX9 for cancer treatment to spare healthy tissue? Emerging strategies focus on targeted delivery. For example, using nanocarriers conjugated with ligands that specifically target cancer stem cells (CSCs) can help deliver SOX9 inhibitors or siRNA directly to tumor cells, thereby reducing exposure to healthy tissues like the intestinal epithelium that rely on SOX9 for repair [25]. Another proposed strategy is to use SOX9 inducers in normal intestinal tissue specifically after high-dose radiotherapy to promote crypt repair and regeneration, while simultaneously inhibiting SOX9 in the tumor [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Efficiency in CRISPR-i Mediated SOX9 Repression

| Observed Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor repression of SOX9 | Inefficient guide RNA (gRNA) design [34]. | Redesign gRNAs targeting the SOX9 promoter or enhancer regions. Use validated design tools and select multiple gRNAs for testing. |

| Low efficiency of RNP delivery [34]. | Switch to a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery format, which often yields higher editing efficiencies and more reproducible results than plasmid-based delivery. | |

| Insufficient dCas9 expression. | Use a high-titer viral vector (e.g., lentivirus) for dCas9 delivery and confirm expression via immunoblotting. Ensure the KRAB or other repressor domain is functional. |

Problem: High Off-Target Effects in shRNA Experiments

| Observed Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unanticipated phenotypic effects | Sequence-dependent off-target silencing [34]. | Use a pool of multiple distinct shRNAs to ensure the phenotype is consistent. Employ bioinformatics tools to predict and minimize off-target binding. |

| Activation of immune responses | Sequence-independent interferon response [34]. | Use validated shRNA constructs with modified nucleotides to reduce immune activation. Use appropriate controls (e.g., scrambled shRNA) to account for non-specific effects. |

Problem: Cytotoxicity from Small-Molecule SOX9 Inhibitors

| Observed Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Death in non-target cells | Lack of specificity of the inhibitor. | Source inhibitors from different vendors or with distinct chemical scaffolds to confirm the on-target effect. Perform a counter-screen against related transcription factors. |

| Impaired tissue regeneration in in vivo models | On-target inhibition of SOX9 in healthy stem cells [25] [1]. | Titrate the inhibitor to the lowest effective dose. Implement intermittent dosing schedules to allow for recovery of repair mechanisms. Monitor tissue health with histology. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol 1: Lentiviral shRNA-Mediated Knockdown of SOX9

Objective: To achieve transient knockdown of SOX9 in mammalian cells for functional studies.

Reagents:

- SOX9-targeting shRNA plasmids (e.g., from MISSION shRNA library)

- Non-targeting scrambled shRNA control plasmid

- HEK-293T cells for virus production

- Target cells (e.g., cancer cell line)

- Packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G)

- Polybrene

- Puromycin

Methodology:

- Virus Production:

- Co-transfect HEK-293T cells with the shRNA plasmid and packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) using a standard transfection reagent.

- Replace media after 6-8 hours. Collect viral supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection.

- Concentrate the virus by ultracentrifugation if necessary.

Target Cell Transduction:

- Plate target cells and transduce with viral supernatant in the presence of 8 µg/mL Polybrene.

- Spinfect by centrifuging plates at 800-1000 x g for 30-60 minutes at 32°C to enhance efficiency.

Selection and Validation:

- 24 hours post-transduction, begin selection with puromycin (dose determined by kill curve) for at least 48 hours.

- Maintain cells for 72-96 hours post-transduction before analysis.

- Validate knockdown efficiency via:

- qRT-PCR: Measure SOX9 mRNA levels relative to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH).

- Western Blot: Probe for SOX9 protein (≈64 kDa) using a specific antibody.

Detailed Protocol 2: CRISPR Interference (CRISPR-i) for SOX9 Repression

Objective: To achieve specific and reversible transcriptional repression of the SOX9 gene.

Reagents:

- Plasmid expressing dCas9-KRAB (e.g., pLV hU6-sgRNA hUbC-dCas9-KRAB-T2a-Puro)

- gRNA expression plasmid or synthetic gRNA targeting the SOX9 promoter

- Lipofectamine 3000 or similar transfection reagent for plasmids; or, for RNP delivery, synthetic gRNA and purified dCas9-KRAB protein.

Methodology:

- gRNA Design and Preparation:

- Design 3-5 gRNAs targeting the region from -50 to -500 bp upstream of the SOX9 transcription start site (TSS).

- Cloning: If using plasmids, clone annealed oligos into the BsmBI site of the gRNA expression vector.

- RNP Complexing: If using RNP, complex purified dCas9-KRAB protein with synthetic gRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2.5 and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes before delivery.

Cell Transfection/Nucleofection:

- For plasmids: Co-transfect the dCas9-KRAB and gRNA plasmids into your target cells using a standard method.

- For RNP: Deliver the pre-complexed RNP into cells via nucleofection for highest efficiency, especially in hard-to-transfect cells.

Analysis:

- Allow 72-96 hours for repression to establish.

- Assess repression efficiency by qRT-PCR and Western Blot, as described in Protocol 1.

- Confirm specificity by checking the expression of unrelated genes and potential off-target genes.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of shRNA, CRISPR-i, and Small-Molecule Inhibitors for SOX9 Inhibition

| Feature | shRNA Knockdown | CRISPR-i | Small Molecule Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | mRNA [34] | DNA (Promoter/Enhancer) [34] | SOX9 protein or its co-factors |

| Level of Intervention | Post-transcriptional [34] | Transcriptional [34] | Post-translational |

| Reversibility | Reversible [34] | Reversible [34] | Reversible (dose-dependent) |

| Typical Efficiency | Moderate to High (≥70% knockdown) | High (≥80% repression) | Varies by compound |

| Key Advantage | Studied in essential genes [34] | High specificity, fewer off-targets [34] | Temporal and dose control [25] |

| Key Limitation | High off-target effects [34] | Persistent effects, delivery complexity [34] | Potential lack of specificity |

| Key Application | Initial functional screens, acute inhibition | Long-term, specific repression studies | Drug development, in vivo studies |

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Gene Silencing Technologies

| Parameter | RNAi (shRNA) | CRISPR (CRISPR-i/Knockout) |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Assess Effect | 3-5 days (knockdown) | 3-7 days (knockout/repression) |

| Editing/Silencing Efficiency | Varies; 50-90% (knockdown) | Often >90% (knockout) [34] |

| Phenotype | Knockdown (mRNA reduced) | Knockout (gene disrupted) or Repression (transcription blocked) |

| Primary Repair Mechanism | N/A (acts via RISC) | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) for knockout; no cleavage for CRISPR-i [34] |

Pathway Diagrams and Visualizations

Experimental Workflow for shRNA & CRISPR-i

SOX9's Dual Role in Cancer and Tissue Repair

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SOX9 Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SOX9 shRNA Plasmids | DNA vectors encoding short hairpin RNAs for RNAi-mediated knockdown of SOX9 mRNA. | Creating stable cell lines with reduced SOX9 expression for proliferation and stemness assays. |

| dCas9-KRAB & SOX9 sgRNAs | A nuclease-deficient Cas9 fused to a KRAB repressor domain and guide RNAs targeting the SOX9 promoter. | Achieving reversible, transcriptional repression of SOX9 without altering the DNA sequence. |

| SOX9 Small-Molecule Inhibitors | Chemical compounds that directly or indirectly disrupt SOX9 protein function or stability. | In vivo studies for cancer therapy or acute in vitro inhibition to study downstream signaling. |

| Anti-SOX9 Antibody | Validated primary antibody for detecting SOX9 protein levels via Western Blot or Immunofluorescence. | Essential validation tool to confirm knockdown/repression efficiency at the protein level. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) for producing lentiviral particles to deliver genetic tools into target cells. | Enables efficient transduction of shRNA or CRISPR-i components into a wide range of cell types. |

| Puromycin | A selection antibiotic that kills non-transduced cells, allowing for the enrichment of successfully transduced cells. | Selection of cell populations stably expressing shRNA or dCas9-KRAB after viral transduction. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Nanocarrier Delivery in SOX9 Research

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Relevant to SOX9 Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Transfection Efficiency | Nanocarrier instability; incorrect N:P ratio; insufficient endosomal escape. | Optimize lipid/polymer to mRNA ratio (N:P ratio); include endosomolytic agents (e.g., chloroquine). | Critical for SOX9 mRNA delivery to chondrocytes [35]. |

| High Cytotoxicity | Cationic nanocarrier surface charge; cytotoxic components; impurities from synthesis. | Use biodegradable lipids (e.g., SM-102); incorporate PEGylated lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) to reduce charge. | Prevents damage to healthy cartilage cells during SOX9 therapy [36] [35]. |

| Rapid Clearance from Blood | Opsonization and uptake by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS). | Functionalize surface with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to create "stealth" nanoparticles. | Extends circulation time for systemic SOX9-targeted delivery [37] [36]. |

| Poor Target Tissue Accumulation | Non-specific distribution; biological barriers (e.g., dense cartilage, tumor microenvironment). | Utilize active targeting with ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies); leverage tissue-specific characteristics (e.g., pH, enzymes). | Essential for reaching SOX9-positive cells in specific tissues [37] [38]. |

| Inconsistent Batch Quality | Non-standardized synthesis methods; variable component purity. | Adopt reproducible microfluidic mixing techniques; implement rigorous physicochemical characterization (size, PDI, zeta potential). | Ensures reproducible SOX9 gene expression and therapeutic outcomes [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary types of nanocarriers used for targeted delivery, and which are most suitable for transcription factor delivery like SOX9?

The primary nanocarriers include lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs), polymeric nanoparticles, and liposomes. For delivering large biomolecules like SOX9 mRNA or plasmids, LNPs are often the most suitable. They are highly efficient in encapsulating nucleic acids, protecting them from degradation, and facilitating cellular uptake and endosomal escape. Recent studies have successfully used optimized LNPs for the co-delivery of SOX5 and SOX9 mRNA into chondrocytes for osteoarthritis treatment, demonstrating high efficacy and reduced inflammation [35].

Q2: How can I assess the potential cytotoxic effects of my nanocarrier formulation on healthy cells?

A combination of in vitro assays is recommended to comprehensively evaluate cytotoxicity, which is crucial when researching SOX9's role in tissue repair. Key methods include:

- Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays: Use kits like Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) or Calcein/PI staining to quantify live and dead cells [35].

- Cell Morphology Observation: Monitor changes in cell shape and adhesion using microscopy.

- Mechanistic Studies: Investigate the generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and mitochondrial membrane potential using assays like JC-1 [36] [35]. These are vital as SOX9 is involved in maintaining cellular function.

Q3: What strategies can I use to improve the nuclear delivery of therapeutics targeting transcription factors like SOX9?

Achieving efficient nuclear delivery is a key challenge. Two main strategies are:

- Passive Nuclear Targeting: Designing nanocarriers small enough (typically <40 nm) to pass through the nuclear pore complex. This can be achieved by modulating the nanocarrier's size, morphology, and surface charge [37].

- Active Nuclear Targeting: Incorporating Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS) into your nanocarrier system. NLS are short peptide sequences that are recognized by importin proteins, which actively transport cargo into the nucleus [37]. This is particularly relevant for strategies aiming to modulate SOX9 gene expression directly.