TKIT Guides: A Precision CRISPR Strategy for Endogenous Protein Tagging and Knock-In

Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides represents a significant advance in CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing, specifically designed to overcome the challenges of precise DNA integration in hard-to-edit cells like neurons.

TKIT Guides: A Precision CRISPR Strategy for Endogenous Protein Tagging and Knock-In

Abstract

Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides represents a significant advance in CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing, specifically designed to overcome the challenges of precise DNA integration in hard-to-edit cells like neurons. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of TKIT that distinguish it from HDR and NHEJ-based methods. We detail its methodological application for tagging synaptic proteins and in vivo modeling, explore advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies using chemical enhancers and donor design, and present validation data demonstrating its high efficiency and reduced translocation frequency compared to conventional techniques. This guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to implement TKIT for robust, precise genome editing in biomedical research.

Beyond HDR and NHEJ: Understanding the TKIT Guide Advantage for Precise Editing

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by functioning as programmable "molecular scissors" that introduce double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations [1] [2]. However, the final editing outcome is not determined by the cutting process itself, but by the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery that responds to these breaks [3]. Two primary competing pathways repair these DSBs: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) [4] [2]. The choice between these pathways presents a fundamental challenge for researchers, particularly when working with post-mitotic cells such as neurons.

HDR serves as the precision repair mechanism that utilizes a homologous DNA template to accurately restore damaged sequences. This pathway enables researchers to introduce specific genetic modifications, including point mutations, insertions, or fluorescent protein tags, by providing an exogenous donor template with homology to the target site [4] [2]. In contrast, NHEJ operates as a quick, error-prone repair process that directly ligates broken DNA ends without requiring a template. This often results in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) that disrupt gene function, making NHEJ ideal for gene knockout studies but problematic when precise editing is desired [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental competition between these two repair pathways after a CRISPR-Cas9 induced double-strand break, which is central to the challenge of precise genome editing.

The HDR Limitation in Post-Mitotic Cells

Cell Cycle Dependence of HDR

A fundamental biological constraint severely impacts HDR efficiency in post-mitotic cells: the HDR pathway is strictly dependent on specific cell cycle phases. HDR requires sister chromatids as natural templates for repair, confining its activity primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [5] [2]. This dependency creates a substantial barrier for genome editing in non-dividing cells, including neurons, cardiomyocytes, and sensory cells, which have exited the cell cycle and therefore lack the necessary cellular machinery and templates for efficient HDR [3] [5].

Recent investigations comparing human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with iPSC-derived neurons have revealed that post-mitotic cells employ distinctly different DSB repair pathways than dividing cells. While iPSCs predominantly utilize microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and generate larger deletions typically associated with resection-dependent repair, neurons exhibit a much narrower distribution of outcomes dominated by NHEJ-like small indels [3]. This pathway preference in post-mitotic cells further compounds the challenge of achieving precise edits.

Kinetic Challenges in Post-Mitotic Cells

The timeline for DNA repair differs significantly between dividing and post-mitotic cells, creating additional hurdles for efficient genome editing. In dividing cells such as iPSCs, Cas9-induced indels typically plateau within a few days post-transduction. In stark contrast, indels in neurons continue to accumulate for up to two weeks after transient Cas9 RNP delivery, indicating a profoundly extended DSB resolution timeline [3]. Similar prolonged indel accumulation has been observed in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, suggesting this may be a common feature of clinically relevant non-dividing cells [3].

This extended repair window has critical implications for editing outcomes: the prolonged exposure of DSBs provides more opportunities for the error-prone NHEJ pathway to act, further reducing the already low HDR efficiency in these cell types. The following table summarizes key quantitative differences in DNA repair characteristics between dividing cells and post-mitotic neurons.

Table 1: DNA Repair Characteristics in Dividing vs. Post-Mitotic Cells

| Characteristic | Dividing Cells (e.g., iPSCs) | Post-Mitotic Cells (e.g., Neurons) |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Efficiency | Higher | Limited/very low |

| Primary Repair Pathways | MMEJ-predominant, broader range of indels [3] | NHEJ-predominant, smaller indels [3] |

| DSB Repair Kinetics | Indels plateau within days [3] | Indels accumulate over weeks [3] |

| Cell Cycle Dependence | HDR active in S/G2 phases [5] | Minimal HDR capacity due to cell cycle exit [5] |

NHEJ Competing Repair and INDEL Formation

NHEJ Pathway Mechanisms

The NHEJ pathway represents the dominant competing repair mechanism that significantly undermines HDR efficiency across all cell types. This error-prone pathway initiates when the Ku protein complex (a heterodimer of Ku70 and Ku80 subunits) recognizes and binds to broken DNA ends, forming a ring-like structure that encircles the duplex DNA [4]. This complex then recruits and activates various processing enzymes, including Artemis nuclease for end trimming and DNA polymerases μ and λ for fill-in synthesis, before ultimately recruiting the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to seal the ends [4].

Unlike HDR, NHEJ operates throughout all phases of the cell cycle and does not require a homologous template [4] [2]. This fundamental characteristic gives NHEJ a significant temporal advantage over HDR, as the pathway can engage DSBs immediately after they occur. The following table outlines the core components and functions of the three major DNA double-strand break repair pathways.

Table 2: Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Repair Pathway | Key Components | Template Required | Typical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical NHEJ (cNHEJ) | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV [4] | No | Small insertions/deletions (INDELs) |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | Polθ, PARP1, Ligase III [6] | No (uses microhomology) | Larger deletions with microhomology signatures |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | BRCA1, BRCA2, Rad51 [4] | Yes (homologous DNA) | Precise edits, gene knock-ins |

Quantifying HDR vs. NHEJ Efficiency

The competitive relationship between HDR and NHEJ is not fixed but varies significantly depending on experimental conditions. Systematic quantification using digital PCR assays has revealed that the HDR/NHEJ ratio is highly dependent on the specific gene locus, nuclease platform, and cell type [7]. Contrary to the widespread assumption that NHEJ generally occurs more frequently than HDR, studies have demonstrated that certain conditions can actually yield more HDR than NHEJ, highlighting the potential for optimizing editing conditions to favor precise outcomes [7].

Recent research in mouse embryos has further refined our understanding of this competition, revealing that the repair pattern of sgRNAs themselves influences knock-in efficiency. sgRNAs with MMEJ-biased repair patterns demonstrate higher knock-in efficiency, while those with NHEJ-biased patterns result in significantly lower integration rates, despite similar initial indel frequencies [6]. This discovery provides important insights for sgRNA selection in precision editing experiments.

Strategic Approaches to Enhance Precise Editing

Modulating DNA Repair Pathways

Several strategic approaches have emerged to overcome the inherent limitations of HDR in post-mitotic cells by modulating DNA repair pathways:

NHEJ Pathway Inhibition: Small molecule inhibitors targeting key NHEJ components, such as AZD7648 (a DNA-PKcs inhibitor), can shift DSB repair toward MMEJ and improve HDR efficiency [6]. This reorientation of repair pathways has been shown to enhance knock-in efficiency in mouse embryos.

MMEJ Pathway Disruption: Knocking down Polθ (encoded by the Polq gene), a crucial mediator of MMEJ, reduces competing repair and can enhance HDR-mediated DNA integration, particularly for MMEJ-biased sgRNAs [6].

Combined Modulation: The ChemiCATI strategy combines AZD7648 treatment with Polq knockdown to create a universal and highly efficient knock-in approach, validated at multiple genomic loci with efficiencies up to 90% in mouse embryos [6].

Alternative Precision Editing Technologies

Beyond modulating endogenous repair pathways, alternative precision editing technologies have been developed that operate independently of HDR:

Base Editing: This technology uses catalytically impaired Cas9 fused to deaminase enzymes to directly convert one base pair to another without inducing DSBs [5]. Since base editing bypasses the need for HDR, it achieves efficient editing in post-mitotic cells with minimal indel formation. In inner ear sensory cells, base editing successfully installed a S33F mutation in β-catenin with a 200-fold higher editing:indel ratio than HDR [5].

Prime Editing: This more recent technology uses a reverse transcriptase fused to Cas9 nickase and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly copy edited genetic information into the target site, achieving precise edits without DSBs or donor templates.

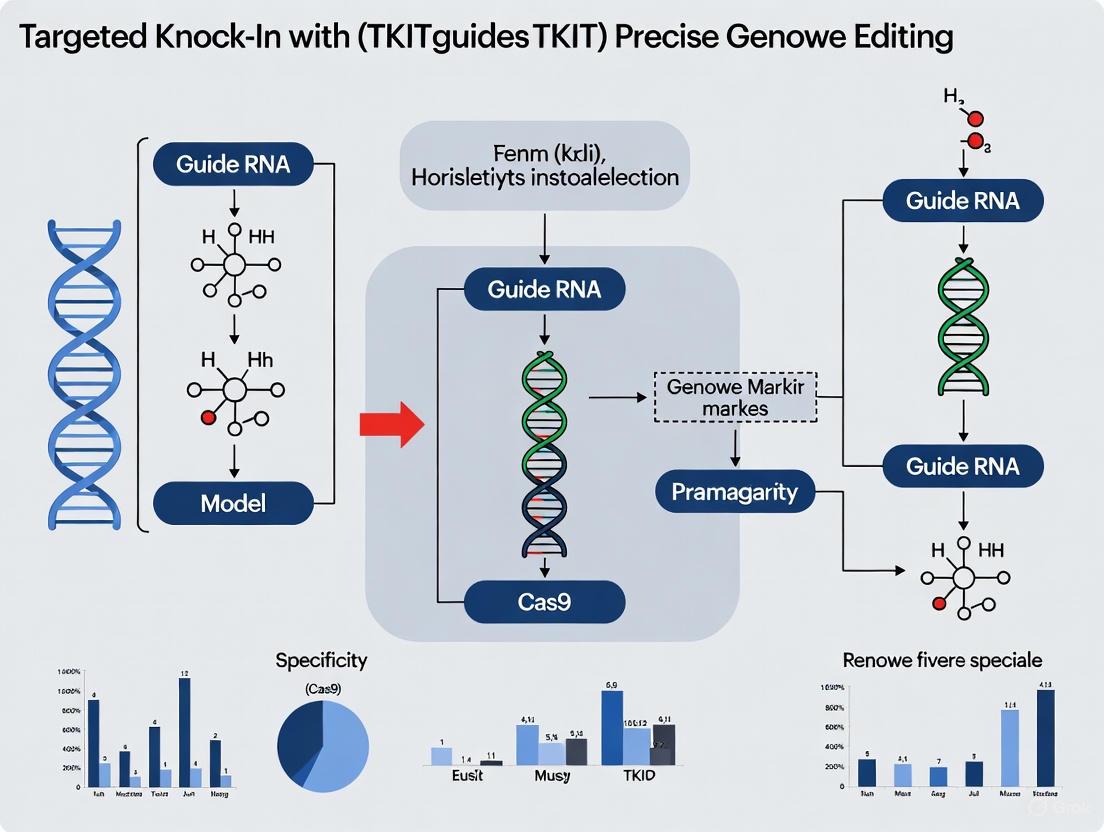

The following diagram illustrates the innovative TKIT (Targeted Knock-In with Two guides) strategy, which represents a significant advancement for precise genome editing in post-mitotic cells by leveraging NHEJ while avoiding INDEL mutations in coding regions.

Application Notes: TKIT Protocol for Neuronal Genome Editing

TKIT Guide RNA Design and Donor Construction

The Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides approach enables precise genomic knock-in in post-mitotic neurons by targeting non-coding regions, thereby avoiding INDEL mutations in protein-coding sequences [8]. The protocol involves:

Guide RNA Selection: Design two sgRNAs targeting non-coding regions (e.g., 5'-UTR and intronic regions) flanking the desired insertion site. Select regions approximately 100 bp away from splice junctions to preserve mRNA processing. Guides should have high on-target efficiency scores and minimal predicted off-target effects [8].

Donor DNA Construction: Create a donor fragment containing: (1) the endogenous sequence with desired insertion (e.g., fluorescent protein tag), (2) homologous genomic sequences flanking the insertion, and (3) the same two guide RNA target sequences with "flipped" orientation and switched positions relative to the genomic DNA. This design enables Cas9 to recognize and re-cut incorrectly integrated donors, increasing the probability of precise forward orientation integration [8].

Vector Preparation: Clone expression constructs containing both sgRNAs with SpCas9, and the donor DNA fragment as a separate plasmid. Include a fluorescent marker (e.g., mCherry) for identification of transfected cells [8].

Neuronal Transfection and Validation

Primary Neuron Transfection: Plate primary mouse cortical neurons and transfert at DIV7-9 using appropriate transfection reagents. Use a plasmid ratio of 1:1:1 for Cas9/sgRNAs, donor DNA, and morphological marker. Maintain neurons for 7-14 days post-transfection to allow for protein expression [8].

Validation Methods:

- Imaging: Confirm successful knock-in through live imaging of fluorescent tags. For SEP-GluA2 knock-in, expect punctate signal concentrated in dendritic spines, consistent with AMPA receptor localization [8].

- Immunostaining: Perform immunofluorescence with antibodies against the tagged protein (e.g., GFP) and the endogenous protein C-terminus (e.g., GluA2) to confirm co-localization [8].

- Molecular Validation: Extract mRNA from transfected neurons, perform RT-PCR, and sequence across splice junctions to verify that knock-in did not disrupt normal mRNA processing [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Precise Genome Editing in Post-Mitotic Cells

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | SpCas9, SaCas9, Cas9-D10A nickase [8] [7] | DSB induction at target sites |

| Pathway Modulators | AZD7648 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor), Polq shRNA [6] | Shift repair toward HDR/MMEJ |

| Donor Templates | dsDNA with homology arms, ssODN [4] [6] | Template for precise HDR editing |

| Delivery Vehicles | Virus-like particles (VLPs), AAVs [3] [8] | Efficient delivery to post-mitotic cells |

| Editing Efficiency Enhancers | ChemiCATI system (AZD7648 + Polq knockdown) [6] | Universal high-efficiency knock-in strategy |

| Alternative Editors | BE3 base editor, prime editors [5] | Precise editing without DSBs |

The fundamental challenge of HDR limitation in post-mitotic cells coupled with competing NHEJ-mediated INDEL formation represents a significant barrier to precise genome editing in clinically relevant cell types. The cell-cycle dependence of HDR and constitutive activity of NHEJ create a biological environment inherently biased against precise edits in neurons and other non-dividing cells. However, emerging strategies including pathway modulation, alternative editors, and innovative approaches like TKIT demonstrate promising avenues to overcome these limitations. By leveraging refined understanding of DNA repair mechanisms and developing creative solutions to bypass inherent biological constraints, researchers can achieve increasingly efficient and precise genomic modifications in post-mitotic cells, advancing both basic research and therapeutic applications for neurological disorders and other conditions affecting non-dividing tissues.

Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides represents a significant advancement in CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing, particularly for post-mitotic cells like neurons where traditional homology-directed repair (HDR) is inefficient. The foundational innovation of TKIT lies in its strategic targeting of non-coding regions flanking the gene of interest, thereby protecting the coding sequence from insertion and deletion (INDEL) mutations that commonly plague conventional editing approaches [8]. This methodology addresses a critical limitation in precision genome editing: the vulnerability of coding sequences to disruptive mutations when directly targeted by CRISPR/Cas9 systems.

Traditional knock-in approaches that target coding sequences directly are susceptible to INDEL mutations at the editing site, which can compromise gene function even when the knock-in is successful [8]. Furthermore, the precise placement of tags is often constrained by the availability of suitable protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) sequences and high-efficiency guide RNAs near the desired insertion site. TKIT overcomes these limitations by repositioning the editing machinery to adjacent non-coding regions, enabling absolute control over the sequence surrounding the knock-in site while preserving the integrity of the protein-coding sequence [8].

Foundational Mechanism and Strategic Advantages

Core Principle: Non-Coding Region Targeting

The TKIT approach utilizes two guide RNAs that create double-strand breaks in non-coding regions flanking the target exon—typically within the 5'-untranslated region (UTR) and downstream intronic sequences [8]. This strategic positioning ensures that the protein-coding sequence remains completely untouched by CRISPR/Cas9 activity, thereby eliminating the risk of INDEL mutations within functionally critical domains. The method employs a donor DNA fragment containing the modified exon (with inserted tag) flanked by the same guide RNA target sequences, but in switched orientation and flipped sequence compared to the genomic DNA [8].

This "switch-and-flip" design in the donor DNA is crucial for promoting correct orientation knock-in through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). When the donor integrates in the reverse orientation, the guide RNA and PAM sequences remain intact, allowing for repeated Cas9 cleavage and subsequent re-attempts at correct integration until either proper orientation is achieved or INDELs destroy the guide recognition sites [8]. This innovative mechanism significantly increases the probability of successful forward-orientation knock-in compared to conventional approaches.

Key Advantages Over Conventional Methods

- Protection of Coding Integrity: By targeting non-coding regions, TKIT completely avoids INDEL mutations in the coding sequence, a significant advantage over HITI (Homology-Independent Target Integration) and other NHEJ-based methods that directly edit coding regions [8].

- Precision Placement: TKIT enables absolute control over the amino acid sequence surrounding the insertion site, allowing for precise tag placement without introducing extraneous amino acids or deleting functional residues [8].

- Expanded Guide RNA Options: Targeting non-coding regions substantially increases the number of potential high-quality guide RNAs, as researchers are not limited to sites within the constrained coding sequence [8].

- Functionality in Post-Mitotic Cells: Unlike HDR-based approaches, TKIT operates efficiently in non-dividing cells such as neurons, making it particularly valuable for neuroscience research [8].

Table: Comparison of TKIT with Conventional Genome Editing Approaches

| Editing Feature | TKIT Approach | Conventional HDR | HITI/NHEJ-based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Non-coding flanks | Coding sequence | Coding sequence |

| INDEL Risk in CDS | None | Low to moderate | High |

| Suitable for Post-mitotic Cells | Yes | No | Yes |

| Insertion Precision | High | High | Variable |

| Guide RNA Availability | Expanded options | Limited by CDS | Limited by CDS |

| Maximum Efficiency (Neurons) | Up to 42% [8] | Very low [8] | 15-25% [8] |

Quantitative Performance Data

TKIT has demonstrated remarkable efficiency across multiple experimental applications. In proof-of-concept studies targeting endogenous synaptic proteins in mouse primary cultured neurons, TKIT achieved knock-in efficiencies of up to 42% when labeling GluA2 AMPA receptor subunits with Super Ecliptic pHluorin (SEP) [8]. This represents a substantial improvement over conventional HITI-based methods, which typically achieve 15-25% efficiency in similar applications while carrying the risk of coding sequence damage.

The methodology has successfully tagged various AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits, including GluA1, GluA2, GluA3, GluN1, and GluN2A, with diverse tags such as SEP, HALO, and Myc tags, demonstrating its versatility across different targets and labeling strategies [8]. Importantly, TKIT-edited neurons exhibited normal synaptic morphology and receptor trafficking, confirming that the approach preserves endogenous protein function while enabling precise labeling.

Table: TKIT Performance Across Different Experimental Applications

| Application Context | Target Molecule | Tag | Efficiency | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mouse Neurons | GluA2 (AMPAR) | SEP | Up to 42% | Spine localization, IF [8] |

| In Utero Electroporation | GluA2 (AMPAR) | SEP | Functional | Two-photon imaging [8] |

| Adult Mouse AAV Injection | GluA2 (AMPAR) | SEP | Functional | In vivo visualization [8] |

| Rat Primary Neurons | GluA2 (AMPAR) | SEP | Comparable to mouse | Cross-species validation [8] |

| FRAP Analysis | Endogenous AMPARs | SEP | N/A | Receptor mobility studies [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

TKIT Workflow for Endogenous Protein Tagging in Neurons

The following protocol outlines the specific methodology for tagging endogenous GluA2 with SEP using TKIT in primary mouse cortical neurons, as described in the foundational TKIT research [8].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Guide RNA Design and Selection (Days 1-2)

- Identify Target Regions: Select non-coding sequences approximately 100 bp away from splice junctions in the 5'-UTR and intron 1-2 of the Gria2 gene (encoding GluA2) [8]. This distance preserves normal mRNA processing while providing sufficient flanking sequence for efficient editing.

- Guide RNA Criteria: Choose guides with high on-target scores and minimal off-target potential using established algorithms. For Gria2 targeting, guides were designed to cut within the 5'-UTR ( upstream of the coding sequence) and within intron 1-2 (downstream of the signal peptide encoding region) [8].

- Control for Coding Integrity: Verify that neither guide RNA targets the protein-coding sequence or critical regulatory elements.

Donor DNA Construction (Days 2-4)

- Template Assembly: Construct a donor DNA fragment containing:

- The endogenous Gria2 sequence from 5'-UTR to intron 1-2

- SEP tag inserted immediately after the signal peptide encoding sequence

- The same two guide RNA target sequences as genomic DNA, but with opposite locations and flipped sequences (switch-and-flip design) [8]

- Vector Cloning: Clone the donor fragment into an appropriate expression vector with necessary regulatory elements for neuronal expression.

Neuronal Transfection and Expression (Days 5-14)

- Cell Preparation: Plate primary mouse cortical neurons at appropriate density and maintain until DIV7-9, ensuring healthy neuronal cultures [8].

- Transfection Mixture: Co-transfect neurons with three components:

- CRISPR/Cas9 construct expressing SpCas9 and both guide RNAs

- SEP-GluA2 donor DNA fragment

- mCherry expression plasmid for visualization of transfected cell morphology [8]

- Optimal Ratios: Use a 2:1:1 mass ratio (Cas9/guides:donor:marker) for optimal knock-in efficiency, as empirically determined in the foundational study [8].

- Incubation: Maintain transfected neurons for 5-7 days (until DIV14-16) to allow for protein turnover and robust expression of edited receptors.

Validation and Functional Assessment (Days 15-21)

- Live Imaging: Visualize SEP fluorescence using standard GFP filter sets; successful knock-in should show punctate signal concentrated in dendritic spines, consistent with AMPAR localization [8].

- Immunofluorescence Validation: Perform co-staining with antibodies against GFP and the C-terminus of GluA2 to confirm co-localization of SEP signal with endogenous GluA2 [8].

- Splicing Integrity: Extract bulk mRNA from transfected neurons (DIV19), perform RT-PCR across the edited region, and sequence to verify intact splice junctions between exon 1 and exon 2 [8].

- Functional Assessment: Compare expression levels of SEP-GluA2 with endogenous GluA2 in non-transfected neighboring neurons to ensure physiological expression levels [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for TKIT Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in TKIT Protocol | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | SpCas9, Guide RNA constructs | Creates targeted DSBs in non-coding flanks | Codon-optimize for target cells; verify nuclear localization |

| Donor DNA Template | SEP-GluA2 fragment with switched-flipped guides | Provides template for precise knock-in | Include homology arms of appropriate length; verify switch-flip design |

| Delivery Vectors | AAV, in utero electroporation, transfection reagents | Introduces editing components into cells | Optimize for cell type; consider size constraints for AAV packaging |

| Visualization Markers | mCherry, eGFP, HALO tags | Identifies transfected cells and edited proteins | Select spectrally distinct fluorophores for multiplexing |

| Validation Reagents | Anti-GFP, anti-GluA2 C-terminal antibodies | Confirms successful knock-in and protein integrity | Verify antibody specificity; use C-terminal tags for endogenous detection |

| Cell Type-Specific Reagents | Primary neuron culture media, viral tropism modifiers | Supports viability of target cells | Optimize for post-mitotic cells; consider developmental expression timing |

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Critical Parameters for Success

- Guide RNA Placement: Position guide RNA cut sites approximately 100 bp from exon-intron boundaries to avoid disrupting RNA splicing machinery while maintaining efficient editing [8]. The exact distance may require optimization for different gene targets.

- Donor Design Fidelity: Meticulously implement the "switch-and-flip" design in the donor DNA, as this significantly enhances correct orientation knock-in by allowing re-cleavage of reverse-integrated donors [8].

- Cell Health Maintenance: Ensure high viability of primary neuronal cultures throughout the procedure, as post-mitotic cells are particularly vulnerable to extended manipulation and CRISPR/Cas9 toxicity.

- Expression Level Validation: Always compare expression levels of knocked-in proteins with endogenous levels in neighboring cells to confirm physiological expression and avoid misinterpretation due to overexpression artifacts [8].

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

- Low Knock-in Efficiency: Optimize the ratio of CRISPR components to donor DNA; typically, a slight excess of donor DNA (2:1 donor:Cas9) improves efficiency. Verify guide RNA activity using surrogate reporter systems before full implementation.

- Unexpected Phenotypes: Always include controls transfected with donor DNA alone to confirm that observed phenotypes require CRISPR activity rather than random integration events [8].

- Imaging Challenges: For pH-sensitive tags like SEP, establish proper imaging conditions (e.g., pH buffering) to ensure accurate signal detection, particularly for surface-exposed proteins like AMPARs [8].

Diagram: TKIT's Self-Correcting Mechanism Through Repeated Cleavage Cycles

The TKIT methodology represents a paradigm shift in precision genome editing by strategically repositioning the editing machinery from vulnerable coding sequences to protective non-coding flanks. This approach achieves unprecedented specificity and preservation of coding integrity while maintaining high efficiency in challenging cell types like neurons. The foundational principle of targeting non-coding regions provides a versatile framework that can be adapted to diverse research contexts, from basic neuroscience to therapeutic development. As genome editing continues to evolve, TKIT's core innovation—protecting coding sequences through strategic non-coding targeting—offers a robust template for future methodological advances in precise genetic manipulation.

Decoding the 'Switch-and-Flip' Donor Design for Orientation-Specific Integration

The "Switch-and-Flip" donor design represents a significant innovation in CRISPR-Cas9-mediated precise genome editing, particularly within the Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides framework. This technical note elucidates the molecular mechanism underlying this design, which ensures unidirectional integration of donor DNA fragments into target genomic loci. By strategically inverting and flipping guide RNA sequences within the donor template, this approach exploits the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway to achieve orientation-specific knock-in with markedly improved efficiency. We provide comprehensive experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and visualization tools to facilitate the adoption of this methodology for labeling endogenous proteins, generating disease models, and advancing therapeutic development.

A fundamental limitation of conventional CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knock-in strategies is their inability to control the orientation of integrated DNA fragments. Traditional NHEJ-based integration results in random insertion orientations, as the cellular repair machinery ligates DNA ends without regard for directionality. This presents a particular challenge for applications requiring precise transcriptional control, such as endogenous gene tagging or the insertion of bidirectional expression cassettes. The "Switch-and-Flip" donor design, implemented within the broader TKIT framework, directly addresses this limitation through a sophisticated molecular strategy that ensures unidirectional integration [9].

The TKIT approach fundamentally differs from conventional knock-in methods by targeting non-coding regions flanking the exonic sequence to be modified, thereby protecting the coding sequence from INDEL mutations and providing absolute control over the sequence surrounding the knock-in site [9]. Within this framework, the "Switch-and-Flip" mechanism serves as the core innovation that enforces orientation-specific integration, overcoming a critical barrier in precision genome editing.

The "Switch-and-Flip" Mechanism: Principles and Design

Core Molecular Components

The "Switch-and-Flip" system functions through several key molecular components that operate in concert:

- Dual guide RNAs: Two sgRNAs targeting non-coding regions upstream and downstream of the coding sequence to be edited, typically located approximately 100 bp away from splice junctions to avoid disrupting mRNA processing [9].

- Cas9 Nuclease: The standard Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 enzyme that creates double-strand breaks at the genomic targets specified by the guide RNAs.

- Donor DNA Fragment: Contains the endogenous sequence with the desired modification (e.g., fluorescent protein tag), flanked by the same two guide sequences as the genome, but with their positions switched and their sequences inverted relative to the genomic DNA [9].

The critical innovation lies in the strategic arrangement of the guide sequences within the donor DNA. By "switching" their positions (the 5' guide is placed at the 3' end and vice versa) and "flipping" their orientation (the sequences are inverted), the system creates a self-correcting mechanism that favors forward orientation integration [9].

Molecular Workflow and Self-Correction Mechanism

The "Switch-and-Flip" mechanism operates through a cyclic process of cutting and re-cutting until correct orientation is achieved:

The diagram above illustrates the self-correcting mechanism of the "Switch-and-Flip" system. When the donor integrates in the reverse orientation, the guide RNA sequences and their associated PAM sites remain intact and properly oriented for recutting by Cas9. This allows for repeated integration attempts until either the correct orientation is achieved or INDEL mutations destroy the guide binding sites, terminating the cycle [9]. This elegant molecular logic ensures that only correctly oriented integrations persist in the edited cell population.

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of the "Switch-and-Flip" donor design has been quantitatively evaluated across multiple experimental systems. The table below summarizes key efficiency metrics reported in foundational studies:

Table 1: Efficiency Metrics of "Switch-and-Flip" Mediated Knock-In

| Target System | Integration Efficiency | Tag Type | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Primary Neurons | Up to 42% | SEP (pH-sensitive GFP) | Endogenous AMPAR labeling | [9] |

| Human Cell Lines (CCR5 Locus) | 33% (clonal analysis) | EGFP | Targeted integration via single crossover | [10] |

| Zebrafish (Composite Tag) | Up to 21% germline transmission | FLAGx3-Bio-HiBiT | Endogenous protein tagging | [11] |

| Human Cell Lines (CCR5 Locus) | 10% (bulk population) | EGFP | Single crossover recombination | [10] |

The "Switch-and-Flip" approach demonstrates particular advantage in non-dividing cells such as neurons, where homology-directed repair (HDR) functions inefficiently. In primary mouse cortical cultures, the system achieved labeling of endogenous synaptic proteins with various tags at efficiencies up to 42% [9]. This represents a substantial improvement over conventional HDR-based methods in post-mitotic cells.

When compared with alternative knock-in strategies, the "Switch-and-Flip" method shows competitive efficiency while maintaining orientation specificity:

Table 2: Comparison of Knock-In Strategies for Large Fragment Integration

| Method | Mechanism | Orientation Control | Typical Efficiency | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Switch-and-Flip" (TKIT) | NHEJ with cyclic recutting | Yes | Up to 42% | Non-dividing cells, precise endogenous tagging |

| HDR (Double Crossover) | Homology-directed repair | Yes | 10⁻⁶–10⁻⁵ [10] | Dividing cells, small modifications |

| NHEJ-based (Conventional) | Direct end joining | No | 0.17–0.45% [10] | Rapid knock-in without orientation requirement |

| Single Crossover Recombination | Campbell-like recombination | Direction-dependent | 33% (clonal) [10] | Large fragment integration in human cells |

Experimental Protocol for TKIT with "Switch-and-Flip" Design

Guide RNA and Donor Design Specifications

Target Selection Criteria:

- Identify non-coding regions approximately 100 bp upstream and downstream of the coding sequence to be modified [9]

- Ensure target sites are at least 50-100 bp away from exon-intron boundaries to preserve RNA splicing [9]

- Select guides with high on-target efficiency scores and minimal predicted off-target effects

Donor DNA Construction:

- Include the endogenous genomic sequence with the desired modification (e.g., fluorescent protein tag)

- Position the two guide sequences at the ends of the donor fragment, but switch their positions (5' genomic guide at 3' of donor, and vice versa) compared to the genomic context

- Invert the sequence orientation of both guides within the donor relative to their genomic configuration [9]

- Maintain intact PAM sequences adjacent to each guide within the donor template

Laboratory Implementation Protocol

Day 1: Cell Preparation

- Plate primary mouse cortical neurons at DIV7-9 or appropriate mammalian cells relevant to your study

- Maintain cells in complete culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS) [12]

- Ensure cells are 60-80% confluent at time of transfection

Day 2: Transfection

- Prepare transfection mixture containing:

- Incubate mixture for 15-20 minutes at room temperature

- Apply to cells following standard transfection protocols for your cell type

Days 3-14: Selection and Expression

- Replace medium 6-24 hours post-transfection

- For stable integration, begin antibiotic selection 48 hours post-transfection if using selection markers

- Culture cells for 10-14 days to allow protein expression and maturation

Day 14+: Validation and Analysis

- Live-image transfected neurons or cells for tag expression (e.g., SEP signal)

- Fix cells for immunofluorescence validation using antibodies against the tag and endogenous protein

- Perform junction PCR and Sanger sequencing to confirm precise integration

- Extract bulk mRNA for RT-PCR to verify intact RNA splicing [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for "Switch-and-Flip" Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Specifications & Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9-NLS | Creates DSBs at target genomic loci | Nuclear localization signal (NLS) essential; alternative: HiFi Cas9 variants for reduced off-target effects |

| Long ssDNA Donor | Repair template for knock-in | Can be chemically synthesized; lssDNA shows superior specificity for on-target integration [11] |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Transfection reagent | Linear, MW 25,000, transfection grade [12] |

| Dual sgRNA Expression Plasmid | Targets non-coding flanking regions | May be expressed as single transcript with ribozyme or tRNA processing elements |

| Selection Antibiotics | Enrichment of transfected cells | Puromycin (2 µg/mL) common for mammalian cells [12] |

| FACS Equipment | Analysis and sorting of edited cells | Enables quantification of knock-in efficiency and isolation of clonal populations |

Applications in Biomedical Research

The "Switch-and-Flip" methodology enables diverse research applications with particular strength in:

Endogenous Protein Labeling: The system has been successfully used to tag AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits with Super Ecliptic pHluorin (SEP) in primary neurons, enabling visualization of endogenous receptor trafficking in live cells [9]. This approach preserves natural transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation while eliminating overexpression artifacts.

In Vivo Imaging: Utilizing in utero electroporation or AAV viral injections, TKIT with "Switch-and-Flip" design can label endogenous proteins in living mice, enabling two-photon microscopy visualization of endogenous AMPA receptors in vivo [9].

Disease Modeling: The precise integration capability facilitates generation of patient-specific disease models by introducing pathological mutations into relevant genomic contexts while maintaining endogenous expression patterns.

Therapeutic Development: The orientation control provided by this system is particularly valuable for knock-in of therapeutic transgenes where proper transcriptional regulation is critical for safe and effective expression.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Low Knock-In Efficiency:

- Validate guide RNA cutting efficiency using T7E1 assay or tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE)

- Optimize donor DNA concentration (typical range 1:1 to 3:1 donor-to-CRISPR ratio)

- Consider chemical modifications to synthetic gRNAs to enhance stability and efficiency [13]

Improper Orientation Integration:

- Verify the "switch-and-flip" configuration of guide sequences in donor template

- Confirm integrity of PAM sequences adjacent to guide sequences in donor

- Extend culture time post-transfection to allow for multiple cycles of correction

Cell Viability Issues:

- Titrate Cas9 expression levels to minimize cytotoxicity

- Utilize ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery instead of plasmid DNA to limit Cas9 exposure duration

- Implement caspase inhibitors or other viability-enhancing compounds during transfection

The "Switch-and-Flip" donor design represents a sophisticated solution to the challenge of orientation-specific integration in precise genome editing. When implemented within the TKIT framework, this approach enables efficient, precise labeling of endogenous proteins with broad applications across neuroscience, drug development, and therapeutic discovery.

Within the rapidly evolving field of precise genome editing, the comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nuclease (TALEN) technologies is critical for research and therapeutic development. Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides represents a sophisticated approach for precise genetic alterations, demanding tools with high specificity, flexibility, and a favorable safety profile. While CRISPR-Cas9 has gained widespread adoption for its simplicity, TALEN technology presents distinct and powerful advantages in the context of advanced strategies like TKIT. This application note details the key advantages of TALENs, focusing on their inherent resistance to insertions and deletions (INDELs), unparalleled flexibility in guide RNA (gRNA) selection due to the absence of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) constraints, and their broader applicability across diverse organisms, including the unique capacity to edit mitochondrial DNA. Understanding these characteristics is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal platform for precise genome engineering applications, particularly where accuracy is paramount [14] [15] [16].

Key Advantages of TALENs for Precision Editing

High Specificity and Resistance to INDELs

A paramount concern in therapeutic genome editing is the introduction of unintended, genotoxic mutations. While all editing tools can cause off-target effects, the fundamental mechanisms of TALENs confer a significantly higher specificity profile compared to first-generation CRISPR-Cas9 systems.

- DNA-Protein Interaction vs. RNA-DNA Hybridization: TALENs recognize their target site through direct protein-DNA interactions. The DNA-binding domain consists of tandem repeats, each specifically recognizing a single base pair via Repeat Variable Diresidues (RVDs) [14] [15]. This highly specific binding mechanism, which occurs in the major groove of DNA, is less tolerant of sequence mismatches than the RNA-DNA hybridization used by CRISPR-Cas9, which can tolerate up to five base-pair mismatches, leading to a higher propensity for off-target cleavage [17] [18].

- Dimeric Nuclease Activity: TALENs function as obligate dimers. A pair of TALEN proteins must bind to opposite DNA strands, flanking the target site, for the FokI nuclease domains to dimerize and create a double-strand break (DSB) [17] [18]. This requirement effectively doubles the length of the target sequence recognition (typically ~36-56 bp total for both binding sites), a length that is statistically unique in any genome, thereby drastically reducing the likelihood of off-target activity [14] [18].

- Reduced Structural Variations: Beyond small INDELs, CRISPR-Cas9 has been associated with large, on-target structural variations (SVs), including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations, which pose substantial safety concerns for clinical applications [19]. Although any DSB-inducing platform can cause SVs, the high-specificity binding and cleavage mechanism of TALENs make such detrimental, large-scale genomic aberrations less frequent [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Off-Target and Structural Variation Profiles between CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Targeting Mechanism | RNA-DNA hybridization [14] | Protein-DNA interaction [14] |

| Mismatch Tolerance | High (up to 5 bp) [17] | Low [17] |

| Typical Total Binding Length | ~20 bp (per gRNA) [17] | ~36-56 bp (for a TALEN pair) [14] [18] |

| Reported Frequency of Off-Target Mutagenesis | High in some studies (≥50%) [14] | Low; often undetected in targeted analyses [18] |

| Risk of Large Structural Variations | More documented, especially with NHEJ inhibition [19] | Also present, but less frequent due to specific cleavage [19] |

Flexibility in gRNA and Target Site Selection

The design of precise knock-in strategies, such as those in TKIT workflows, is often constrained by the genomic context of the target locus. TALENs offer superior flexibility in these scenarios.

- No PAM Sequence Requirement: The targeting of the most commonly used CRISPR-Cas9 system from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) is dependent on the presence of a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence immediately adjacent to the target site [18] [16]. This requirement can severely limit the number of potential target sites, especially when a specific nucleotide needs to be edited within a narrow window. In contrast, TALENs have no PAM constraint, allowing researchers to design proteins to target virtually any genomic sequence, providing unparalleled design freedom [15] [20].

- Precise DSB Placement for Enhanced HDR: The absence of a PAM allows TALEN binding sites to be positioned in closer proximity to the intended edit. This closer placement of the induced DSB to the site of homology-directed repair (HDR) can lead to improved knock-in efficiency compared to CRISPR-Cas9, where the PAM dictates the cleavage location, which may be distantly located from the desired edit [20].

- Overcoming Epigenetic Barriers: TALENs can be designed to avoid or overcome epigenetic modifications like cytosine methylation (common at CpG islands). While CpG methylation can inhibit TALEN binding, this can be circumvented during the design phase by selecting target sites devoid of methylated bases or by using specific RVDs (e.g., N*) that can interact with methylated cytosines [18]. CRISPR-Cas9 is generally considered less sensitive to DNA methylation [18].

Applicability Across Broader Organisms and Organelles

The utility of a genome-editing tool is measured by its performance across diverse experimental and therapeutic systems. TALENs demonstrate distinct advantages in several contexts.

- Mitochondrial Genome Editing (mitoTALENs): A unique and powerful application of TALENs is the ability to target and edit mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The guide RNA of the CRISPR-Cas9 system is difficult to import into the mitochondria, making CRISPR ineffective for this purpose. MitoTALENs, however, can be engineered with mitochondrial localization signals to directly manipulate mtDNA, opening avenues for researching and treating mitochondrial diseases [14].

- Efficacy in Diverse Cell Types and Organisms: Both TALENs and CRISPR have been successfully used in a wide range of organisms, including plants, livestock (cows, pigs, chickens), and human cell lines [14] [15]. TALENs have proven highly efficient in plant systems, for instance, where they have been used to enhance the synthesis of valuable secondary metabolites by precisely editing biosynthetic pathways [15].

- Therapeutic Precision: In clinical applications, where safety is the highest priority, the high specificity of TALENs makes them an indispensable tool. Their lower off-target profile is a critical advantage for therapeutic genome editing, as it minimizes the risk of genotoxic side effects that could lead to oncogenesis [14] [19].

Diagram 1: A comparative overview of TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 fundamental mechanisms and their direct implications for key editing characteristics. Green nodes represent distinct advantages of TALENs, while red nodes indicate relative limitations of CRISPR-Cas9 in these areas.

To aid in the objective evaluation and selection of the appropriate genome editing tool, the following tables summarize key performance metrics and design parameters.

Table 2: Comparative Efficiency and Specificity Metrics of Genome Editing Tools

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-Target Indel Efficiency | High (can be >70%) [18] | High (e.g., ~33% and higher reported) [18] | Efficiency is highly dependent on cell type, delivery, and target site. |

| Off-Target Mutation Frequency | High prevalence (≥50%) reported in some studies [14] | Low; often undetected in targeted analyses [18] | CRISPR off-targets can be reduced with high-fidelity variants and paired nickases [17] [19]. |

| HDR Efficiency | Moderate, but can be limited by PAM location [20] | High potential due to flexible target site selection and close DSB placement [20] | HDR is inherently less efficient than NHEJ in human cells [16]. |

| Relative Cost & Ease of Construction | Low cost; simple gRNA cloning [17] [20] | Higher cost; more complex protein engineering [20] | TALEN construction has been streamlined with modular kits [17] [18]. |

Table 3: Key Design and Targeting Constraints

| Design Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 (spCas9) | TALENs |

|---|---|---|

| Target Recognition Length | ~20 bp (per gRNA) [17] | ~18 bp (per monomer, ~36 bp total for a pair) [17] [18] |

| PAM/PAM-like Requirement | Yes (5'-NGG-3') [18] [16] | No [15] [20] |

| Methylation Sensitivity | Less sensitive [18] | Sensitive to CpG methylation (can be designed around) [18] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (via multiple gRNAs) [21] | Low (due to large protein size and complex cloning) [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing and Assembling TALEN Constructs for a TKIT Experiment

This protocol outlines the steps to design and clone TALEN pairs for a targeted knock-in experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- TALEN Kit: Commercial kits (e.g., from companies like GeneCopoeia or Thermo Fisher Scientific) provide pre-validated, modular RVD plasmids for streamlined assembly [18] [20].

- FokI Nuclease Plasmid: Vector backbone containing the catalytic domain of the FokI restriction enzyme for nuclease activity [14] [15].

- Delivery Vector: AAV, lentiviral, or plasmid vectors suitable for your target cell type. Note: TALEN's large size can be challenging for AAV packaging [14] [22].

Procedure:

- Target Site Identification: Using genomic sequence data, select a 30-40 bp target region encompassing your desired edit. The spacer sequence (where the cut will occur) should be 14-20 bp long [17] [18].

- TALEN Pair Design: Design two TALEN binding sites, each 15-20 bp long, flanking the spacer. Avoid target sites with high CpG methylation unless using specific RVDs. Use the RVD code: NI for A, HD for C, NN for G, and NG for T to define the amino acid sequence of the DNA-binding domain for each TALEN [14] [18].

- In Silico Validation: Use software tools (e.g., Thermo Fisher's TrueDesign Genome Editor) to validate specificity and check for potential off-target sites in the relevant genome [20].

- Modular Assembly: Perform a Golden Gate assembly reaction using a commercial TALEN kit. This involves ligating the pre-defined RVD modules into the FokI nuclease backbone plasmid in a specific order corresponding to your target sequence [18] [21].

- Sequence Verification: Confirm the final TALEN plasmid sequence via Sanger sequencing. This is crucial due to the repetitive nature of the TALEN sequence, which can pose challenges for cloning and sequencing fidelity [18].

Protocol 2: Delivering TALENs and Donor Template for HDR in Cultured Cells

This protocol describes the co-delivery of TALENs and a donor DNA template to achieve precise knock-in via HDR.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- TALEN Expression Plasmids: The two verified TALEN plasmids from Protocol 1.

- HDR Donor Template: A single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or a double-stranded DNA plasmid containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms (typically 800-1000 bp each for plasmid donors) [18].

- Transfection Reagent: A reagent suitable for your cell type (e.g., lipofection, electroporation kits). For hard-to-transfect cells, consider nucleofection [20].

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed and culture the target cells to reach 70-90% confluency at the time of transfection.

- Transfection Complex Formation: For a single well of a 24-well plate, prepare a transfection mixture containing:

- 0.5 µg of each TALEN plasmid (1 µg total)

- 100-200 pmol of ssODN donor OR 0.5-1 µg of donor plasmid

- Optimum volume of transfection reagent, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Incubate with the cells.

- Post-Transfection Culture: Replace the transfection medium with fresh culture medium after 6-24 hours.

- Harvest and Validation: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection for initial analysis of editing efficiency.

Protocol 3: Validating Knock-In and Screening for Off-Target Effects

A critical step to confirm successful on-target editing and assess specificity.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Surveyor Nuclease or T7 Endonuclease I: Enzymes for mismatch detection assays to identify heterogeneous pools of edited cells [22].

- PCR Reagents: For amplifying the genomic target region and potential off-target sites.

- Sanger Sequencing or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Reagents: For definitive confirmation of edits and comprehensive off-target profiling.

Procedure:

- On-Target Efficiency Analysis (Initial Screening):

- Extract genomic DNA from transfected cells.

- PCR-amplify the genomic region surrounding the target site.

- Use the T7E1 or Surveyor assay on the PCR product. Cleaved bands indicate the presence of indels, suggesting successful DSB and NHEJ/HDR repair [22].

- Clonal Isolation and Validation:

- If a clonal population is required, perform serial dilution of the transfected cell pool to isolate single cells.

- Expand monoclones for 2-3 weeks.

- Screen monoclones by PCR and T7E1 assay, then sequence the top candidates via Sanger sequencing to identify clones with the precise HDR-mediated knock-in and biallelic modification [22].

- Off-Target Assessment:

- Perform an in silico analysis to predict potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity to the TALEN binding sites.

- Amplify the top 10-20 predicted off-target loci from genomic DNA of edited clonal lines and a control line.

- Analyze these amplicons by deep sequencing (NGS) to quantify the frequency of indels at these sites, confirming the high specificity of TALENs [18] [19].

Diagram 2: A comprehensive workflow for a TALEN-mediated TKIT experiment, from initial design and assembly to final validation. Key protocol steps involving specialized reagents or critical decisions are highlighted in yellow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for TALEN-Mediated Editing

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TALEN Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example Suppliers / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Custom TALEN Constructs | Engineered plasmids encoding the TAL effector DNA-binding domain fused to FokI nuclease. | GeneCopoeia, Thermo Fisher Scientific; available as ready-to-use expression vectors [18] [20]. |

| TALEN Modular Assembly Kits | Kits containing pre-made RVD modules for streamlined, cost-effective Golden Gate assembly of custom TALENs. | Addgene (distributes academic kits); commercial suppliers [18]. |

| HDR Donor Templates | Single-stranded ODNs or double-stranded DNA plasmids with homology arms, serving as the repair template for precise knock-in. | Synthesized by commercial oligo/plasmid synthesis companies (e.g., IDT, Thermo Fisher) [18]. |

| High-Efficiency Transfection Reagents | Chemical-based reagents (e.g., lipofection) for delivering TALEN constructs and donor templates into cultured cells. | Thermo Fisher (Lipofectamine), Promega, Roche [20]. |

| Electroporation/Nucleofection Systems | Instrument systems for physically delivering constructs into hard-to-transfect cell types (e.g., primary cells, stem cells). | Lonza Nucleofector, Bio-Rad Gene Pulser [20]. |

| Genomic DNA Isolation Kit | For high-quality, PCR-ready genomic DNA extraction from edited cells. | QIAGEN, Thermo Fisher, Promega. |

| T7 Endonuclease I / Surveyor Nuclease | Mismatch cleavage detection enzymes for initial, rapid assessment of editing efficiency in a mixed cell population. | New England Biolabs (NEB), Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) [22]. |

| NGS-based Off-Target Kit | Kits designed for targeted amplification and deep sequencing of potential off-target sites genome-wide. | IDT (xGen), Illumina; used for comprehensive safety profiling [19]. |

Implementing TKIT: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Donor Design to In Vivo Application

Precise genome editing requires strategies that maximize on-target efficiency while minimizing unintended mutations. The Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides approach represents a significant advancement in this field by utilizing two guide RNAs that cut genomic DNA in flanking non-coding regions, enabling precise insertion of genetic payloads while protecting the coding sequence from insertion/deletion (INDEL) mutations [8]. This method is particularly valuable for post-mitotic cells like neurons, where traditional homology-directed repair (HDR) methods are inefficient [8]. By targeting the 5' untranslated region (5'UTR) and intronic regions, TKIT overcomes limitations associated with coding sequence targeting, including frameshift mutations and PAM sequence constraints, while providing greater flexibility in guide RNA selection [8].

The strategic positioning of gRNAs in non-coding regions enables absolute control over the sequence surrounding the knock-in site and preserves the integrity of the protein-coding sequence. This technical note provides comprehensive guidance on gRNA selection and positioning for optimized TKIT experiments, supported by quantitative data, detailed protocols, and practical visualization tools.

Strategic Positioning of gRNAs for Optimal Knock-In Efficiency

5'UTR-Targeting Knock-In Strategy

Targeting the 5'UTR for knock-in presents a unique opportunity for highly efficient protein tagging while maintaining endogenous regulatory control. Research demonstrates that a 5'UTR-targeting knock-in strategy enables the establishment of stable cell lines expressing tagged proteins with remarkable efficiencies ranging from 50% to 80% in antibiotic-selected cells [23]. This approach positions the knock-in cassette upstream of the native coding sequence, allowing expression under the control of the endogenous promoter while avoiding disruption of the protein-coding region.

The 5'UTR strategy demonstrates several advantages over traditional approaches. The localization of knock-in proteins is identical to that of endogenous proteins in wild-type cells and shows homogenous expression [23]. Moreover, expression from the endogenous promoter remains stable over long-term culture, addressing a significant limitation of systems relying on exogenous promoters [23]. This method has been successfully applied for tagging diverse proteins including Arl13b-Venus, Reep6-HA, and EGFP-alpha-tubulin, demonstrating its broad applicability [23].

Table 1: Efficiency Comparison of Knock-In Strategies

| Strategy | Target Region | Typical Efficiency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5'UTR-targeting [23] | 5' Untranslated Region | 50-80% | Maintains endogenous regulation; avoids protein disruption |

| TKIT guides [8] | 5'UTR + Intron | Up to 42% (in neurons) | Protects coding sequence from INDELs; precise insertion control |

| HDR-based coding sequence targeting [23] | Protein-coding exon | Often very low | Traditional approach; can be combined with selection markers |

| ROSA26 safe harbor [23] | Genomic safe harbor | Variable | Predictable expression; well-characterized locus |

TKIT Guide RNA Design Principles

The TKIT approach utilizes two guide RNAs strategically positioned in non-coding regions flanking the coding sequence of interest. Optimal design places one gRNA within the 5'UTR and the second within the first intron, typically approximately 100 base pairs away from splice junctions to avoid disrupting mRNA processing [8]. This positioning ensures the entire coding sequence can be replaced with a tagged version while preserving native splicing mechanisms.

The donor DNA fragment in TKIT contains the endogenous gene sequence with the desired tag addition, flanked by the same two guide RNA target sequences present in the genome, but in opposite orientation (switch-and-flip design) [8]. This design promotes forward insertion of the donor DNA through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). If the donor inserts in the reverse orientation, the guide RNA and PAM sequences remain intact and can be cut again by Cas9, providing additional opportunities for correct orientation insertion [8].

Table 2: TKIT Guide RNA Design Parameters

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 5'UTR gRNA position [8] | ~100 bp from start codon | Avoids disruption of translation initiation elements |

| Intronic gRNA position [8] | ~100 bp from splice junctions | Preserves RNA splicing mechanisms |

| Homology arm length | Not required | TKIT utilizes NHEJ rather than HDR pathway |

| Donor design [8] | Switch-and-flip orientation | Promotes forward insertion through repeated cutting of reverse inserts |

| Tag positioning | After signal peptide (for secreted proteins) [8] | Ensves proper protein folding and localization |

| PAM consideration [24] | NGG for S. pyogenes Cas9 | Essential for Cas9 recognition and cutting |

Experimental Protocol for TKIT Guide Implementation

gRNA Design and Validation Workflow

Step 1: Target Site Selection

- Identify the 5'UTR region approximately 100 bp upstream of the start codon [8]

- Identify the first intronic region approximately 100 bp downstream from the exon-intron boundary [8]

- Use established gRNA design tools (e.g., Broad Institute GPP sgRNA Designer, CHOP-CHOP) to select optimal sequences [23] [24]

- Verify absence of known polymorphisms in target sequences

- Analyze potential off-target effects using specialized algorithms [24]

Step 2: gRNA Construction

- Clone each 20-bp target sequence into appropriate Cas9-expression plasmid vectors [23]

- For the 5'UTR-targeting gRNA, include the target sequence and 3-bp PAM sequence upstream of the fusion protein sequences in donor constructs [23]

- Apply typical Kozak sequence (GCCACC) for the target genes when designing donor templates [23]

Step 3: Donor DNA Design

- Construct donor plasmid vectors with removal of exogenous promoters (e.g., CMV) to ensure endogenous promoter control [23]

- For fluorescent protein tagging, use pEGFP backbone vectors or similar with the 20-bp target sequence and 3-bp PAM sequence sub-cloned upstream of the fusion proteins [23]

- Implement the "switch-and-flip" design where the two guides within the donor have opposite locations and flipped sequences compared to the genomic DNA [8]

Step 4: Validation of Knock-In Efficiency

- Transfect primary cultures (e.g., mouse cortical cultures at DIV7-9) with plasmids containing both guide RNAs, SpCas9, and the donor DNA fragment [8]

- Include a fluorescent marker (e.g., mCherry) for cell morphology identification [8]

- Assess knock-in efficiency 7-14 days post-transfection via live imaging and immunofluorescence [8]

- Confirm normal RNA splicing through RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing of splice junctions [8]

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Efficiency

The TIDE (Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition) method provides a simple, rapid, and cost-effective strategy to accurately quantify editing efficacy and simultaneously identify the predominant types of insertions and deletions (indels) in targeted cell pools [25]. This method requires only two parallel PCR reactions followed by a pair of standard capillary sequencing analyses, with the resulting sequencing traces analyzed using specialized decomposition algorithms [25].

For TKIT experiments, assess knock-in efficiency through:

- Fluorescence quantification: Compare signal intensity in transfected versus non-transfected cells

- Immunostaining: Verify co-localization of the tag (e.g., GFP) with the target protein (e.g., GluA2 C-terminus) [8]

- Functional validation: Confirm normal cellular localization and behavior of the tagged protein [23]

- Long-term stability: Monitor expression stability over multiple cell passages [23]

Research Reagent Solutions for TKIT Experiments

Table 3: Essential Reagents for TKIT Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems [23] | CMV-Cas9-2A-GFP plasmid | Provides Cas9 nuclease and tracking; 2A peptide enables co-expression of fluorescent marker |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors [23] | pEGFP backbone vectors | Standardized backbones for gRNA expression and donor construct assembly |

| Donor Template Plasmids [23] | p5'UTRgRNA-Arl13b-Venus, p5'UTRgRNA-Reep6-HA | Custom donor constructs with specific tags; CMV promoter removed for endogenous regulation |

| Validation Tools [25] | TIDE web tool (http://tide.nki.nl) | Algorithm-based decomposition of sequencing traces for precise quantification of indels |

| Cell Culture Reagents [8] | Primary mouse cortical cultures | Relevant cellular models for testing knock-in efficiency, especially in post-mitotic cells |

| Selection Markers [23] | Neomycin-resistant gene expression cassette | Enriches for successfully edited cells when included in donor constructs |

Technical Considerations and Troubleshooting

Optimizing Knock-In Efficiency

Several factors significantly impact the success of TKIT experiments. When implementing 5'UTR-targeting strategies, ensure that:

- The Kozak sequence (GCCACC) is included for optimal translation initiation [23]

- AUG codons are removed from synthetic 5'UTRs by randomly mutating one of the three nucleotides to prevent generation of upstream open reading frames [26]

- 5'UTR length is optimized (approximately 100 bp shown effective) to balance regulatory element inclusion and practical constraints [26]

For challenging targets where efficiency remains low, consider:

- Utilizing high-fidelity Cas9 variants to reduce off-target effects

- Implementing fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich successfully edited cells

- Incorporating antibiotic selection cassettes in the donor DNA for stable cell line generation [23]

Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Low Knock-In Efficiency

- Verify gRNA cutting efficiency using TIDE analysis before proceeding with full TKIT experiment [25]

- Optimize donor DNA concentration and configuration (e.g., switch-and-flip design) [8]

- Consider cell cycle synchronization to enhance NHEJ activity

Protein Mislocalization

- Confirm tag positioning does not interfere with signal peptides or localization domains [8]

- Verify endogenous promoter-driven expression produces appropriate expression levels [23]

- Compare localization patterns with antibody staining of endogenous protein

Integration Site Analysis

- Perform PCR amplification across both integration junctions to verify precise insertion [8]

- Sequence the entire edited locus to rule offtarget integrations

- Validate mRNA splicing patterns through RT-PCR analysis of splice junctions [8]

The strategic selection and positioning of guide RNAs in 5'UTRs and introns, as implemented in the TKIT approach, provides a robust framework for precise genome editing with broad applications in functional genomics and therapeutic development.

Precise genome editing via homology-directed repair (HDR) enables the targeted integration of exogenous DNA sequences, such as fluorescent protein tags, affinity epitopes, or other genetic payloads, into specific genomic loci [27]. This process requires a donor DNA template containing the desired insert flanked by homology arms that facilitate recombination with the target genome [28]. The design of this donor DNA fragment is a critical determinant of knock-in efficiency, especially when combined with advanced CRISPR-Cas systems like the Targeted Knock-In with Two (TKIT) guides approach [29].

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has significantly simplified the creation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) at predetermined genomic sites, thereby stimulating cellular repair mechanisms [30]. While the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway often introduces indels, providing a donor template with homologous sequences can steer repair toward HDR for precise integration [31]. This protocol details the strategic design of donor DNA fragments, focusing on the optimization of homology arms and functional sequences to maximize HDR efficiency in TKIT-guided experiments for drug development and functional genomics applications [32].

Structural Components of a Donor DNA Fragment

A donor DNA template for HDR is composed of several key elements, each serving a distinct function in the recombination process. The central component is the cargo sequence, which can range from short epitope tags (e.g., FLAG, HA) to larger functional cassettes such as fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP) or selectable markers [31]. This cargo is flanked by two homology arms—regions with sequence identity to the genomic target—which are essential for strand invasion and the recombination process [28].

The length of these homology arms must be carefully optimized based on the experimental system and cargo size. For large DNA fragment knock-ins (1–3 kb), studies have demonstrated that specially designed 3′-overhang double-strand DNA (odsDNA) donors harboring 50-nucleotide homology arms can achieve high efficiency when combined with CRISPR-Cas9 technology [30]. In zebrafish models, successful integration of large reporter genes like GFP typically requires longer double-stranded DNA fragments with homologous arms, each exceeding 2 kb [28].

Table 1: Recommended Homology Arm Lengths for Different Applications

| Application Context | Cargo Size | Recommended Arm Length | Donor Type | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short sequence insertion (SSA) | < 100 bp | 50–200 nt | ssOligo | Higher efficiency but potentially lower accuracy [28] |

| Large fragment knock-in (LOCK method) | 1–3 kb | 50 nt | odsDNA (with 3′ overhangs) | Uses microhomology-mediated end joining; includes PT modifications [30] |

| Gene-sized KI in mammalian cells | ~1–3 kb | 50 nt | odsDNA | Combined with Cas9-PCV2 fusion protein [30] |

| HR in zebrafish (large reporters) | ~GFP | >2 kb | dsDNA | Requires longer arms for successful homologous recombination [28] |

Additional sequence modifications can enhance donor functionality. Incorporating phosphorothioate (PT) modifications at the 3′-overhangs of odsDNA donors can protect against exonuclease degradation and improve nuclear stability [30]. Furthermore, mutating the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence in the homology arms is crucial to prevent Cas9 from cleaving the donor template itself after integration [31].

Designing Homology Arms for Optimal Efficiency

Length Optimization Strategies

Homology arm length significantly influences HDR efficiency and requires careful balancing. Excessively long arms may complicate vector construction without substantially improving efficiency, while very short arms can dramatically reduce recombination rates [28]. The LOCK method demonstrates that with specific structural modifications, relatively short homology arms of 50 nucleotides can efficiently mediate the knock-in of gene-sized fragments (1–3 kb) in mammalian cells [30].

For more conventional dsDNA donors in zebrafish models, research indicates that homologous arms greater than 2 kb are recommended when inserting large reporter genes like GFP [28]. This length provides sufficient sequence context for the cellular recombination machinery to engage with the donor template. When designing homology arms, it is essential to amplify these sequences from the genomic DNA of the target organism to ensure perfect sequence identity, as even single-nucleotide polymorphisms can significantly reduce HDR efficiency [28].

Strategic Placement and Modifications

The placement of homology arms relative to the CRISPR-induced break site critically impacts recombination efficiency. The DSB should occur within the region spanned by the homology arms, preferably close to the center [33]. Research indicates a dramatic drop in knock-in efficiency when the cut site is not proximal to the insertion site of the repair template [33].

Strategic modifications to the donor DNA can further enhance HDR rates. The LOCK method utilizes odsDNA donors with 3′-overhangs and 50-nt homology arms, which have shown to improve HDR efficiencies by up to 5-fold compared to conventional donors [30]. These designs can be combined with Cas9 fusion proteins (e.g., Cas9-PCV2) to tether the donor DNA in proximity to the cleavage site, thereby increasing local donor concentration and facilitating recombination [30].

Donor Types and Delivery Considerations

Comparing Donor DNA Formats

The physical form of the donor DNA significantly impacts knock-in efficiency and requires consideration based on the experimental goals. Each format offers distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Donor DNA Formats for HDR

| Donor Type | Optimal Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Stranded Oligonucleotides (ssOligos) | Short insertions (<100 nt), point mutations | High efficiency, commercially synthesizable [28] | Lower accuracy, limited cargo capacity [28] |

| Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Large insertions (reporters, cassettes) | Higher accuracy, suitable for large fragments [28] | Lower efficiency, more complex delivery [28] |

| 3′-Overhang dsDNA (odsDNA) | Gene-sized KI (1–3 kb) in mammalian cells | 5× higher HDR efficiency, enhanced stability [30] | Requires special preparation with PT modifications [30] |

| Viral Vectors (AAV) | Difficult-to-transfect cells | High transduction efficiency, nuclear delivery [30] | Limited packaging capacity, potential immune responses |

For precise nucleotide substitutions in zebrafish models, dsDNA donor templates are generally preferred over ssOligos due to their higher accuracy, despite potentially lower efficiency [28]. The LOCK method represents an advanced hybrid approach that leverages advantages from both dsDNA and ssDNA donors through its unique odsDNA structure [30].

Delivery Methods for Donor DNA

Effective delivery of donor DNA into target cells remains a critical challenge in genome editing. The highly negatively charged phosphoric backbone of DNA naturally impedes transportation across cellular membranes, limiting accessibility to DSB sites [30]. Various strategies have been developed to overcome this barrier:

- Physical methods: Electroporation and microinjection directly introduce donor DNA into cells or embryos [31]

- Cationic lipids: Lipid nanoparticles can complex with DNA to facilitate cellular uptake

- Viral vectors: AAV vectors promote nuclear entry but have limited packaging capacity [30]

- Protein fusions: Strep-biotin labeled tethering or Cas9-PCV2 fusions can co-localize donors with Cas9 [30]

- Chromatinized packaging: Donor DNA packaged into chromatin mimics its natural state, potentially enhancing recombination [30]

The choice of delivery method should consider cell type, donor size, and desired efficiency. For large DNA fragments in mammalian cells, the LOCK method's approach of tethering odsDNA donors to Cas9-PCV2 fusion protein has demonstrated significant improvements in knock-in efficiency [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Donor Design

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Donor DNA Design and Knock-In

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Q5 High-Fidelity 2× Master Mix | PCR amplification of homology arms and cargo | Ensures error-free amplification of donor fragments [30] |

| GeneJET PCR Purification Kit | Purification of donor DNA fragments | Removes enzymes, salts, and impurities post-amplification [30] |

| Lambda Exonuclease | Preparation of 3′-overhang dsDNA | Creates specialized odsDNA donors for LOCK method [30] |

| Phosphorothioate-modified Nucleotides | Donor stabilization | Incorporated at 3′-overhangs to protect against exonuclease degradation [30] |

| Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V | Delivery of donor DNA to mammalian cells | Enables efficient transfection of hard-to-transfect cells [30] |

| HisTrap Fast Flow Columns | Purification of Cas9-PCV2 fusion protein | For tethering approaches that co-localize donor with Cas9 [30] |

Experimental Protocol: Donor Design for TKIT-Guided Knock-In

Step-by-Step Design Workflow

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for designing and implementing donor DNA fragments for precise knock-in applications using the TKIT guide system.

Step 1: Target Site Selection and Analysis

- Identify paired TKIT guide RNA target sites flanking the desired integration locus

- Map the precise DSB locations relative to the intended homology arms

- Verify target sequence in the specific cell line or organism to avoid polymorphic regions that could reduce HDR efficiency [28]

Step 2: Homology Arm Design and Preparation

- Determine optimal arm length based on cargo size and experimental system (refer to Table 1)

- Amplify homology arms from genomic DNA of the target organism to ensure sequence identity [28]

- For odsDNA donors: incorporate 50-nt homology arms and design 3′-overhangs with five consecutive phosphorothioate modifications [30]

Step 3: Cargo Sequence Optimization

- Incorporate the functional payload (tag, reporter, etc.) with appropriate regulatory elements

- Introduce silent mutations in the PAM sequence within the homology arms to prevent re-cleavage of integrated donor [31]

- Include diagnostic features such as restriction sites or primer binding sites for screening

Step 4: Donor DNA Assembly and Validation

- Clone the complete donor construct using Gibson assembly or similar methods

- For LOCK method: generate 3′-overhangs using lambda exonuclease treatment [30]

- Sequence-verify the final donor construct, paying special attention to homology arm sequences

Step 5: Delivery and Experimental Validation

- Co-deliver the donor DNA with TKIT guides and Cas9 using appropriate methods (nucleofection, microinjection, etc.)

- Include controls without donor template to assess NHEJ background

- Validate knock-in efficiency using targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) as the gold standard [34]

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low HDR efficiency: Consider tethering approaches like Cas9-PCV2 fusions [30], optimize homology arm length [28], or use specialized donor formats like odsDNA [30]