Troubleshooting Protein Crystallization Failures: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and overcome common protein crystallization failures.

Troubleshooting Protein Crystallization Failures: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and overcome common protein crystallization failures. Covering foundational principles to advanced optimization techniques, it details the critical roles of sample purity, stability, and biochemical parameters. The guide explores systematic screening methodologies, practical troubleshooting for poor crystal quality, and validation strategies using historical data and Al-driven tools, aiming to transform a traditionally empirical process into a more predictable and successful endeavor.

Understanding the Root Causes of Crystallization Failure

The Critical Importance of Sample Purity and Homogeneity

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Sample Purity and Homogeneity Issues

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common sample preparation problems that hinder protein crystallization.

Problem 1: Consistently Failing Crystallization Trials

- Potential Cause: Inadequate sample purity or conformational heterogeneity.

- Solutions:

- Verify Purity: Use SDS-PAGE to confirm a purity level of >95% [1]. Check for and remove any affinity tags that might interfere with crystallization [2] [3].

- Assess Conformational Homogeneity: Utilize Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to ensure the sample is monodisperse and not prone to aggregation [2] [4] [5]. A polydisperse sample indicates heterogeneity.

- Improve Construct Design: Use prediction tools like AlphaFold3 to identify and eliminate flexible protein regions that induce conformational heterogeneity [2] [6].

Problem 2: Crystals Form but Diffract Poorly

- Potential Cause: Micro-heterogeneity or impurities disrupting the crystal lattice.

- Solutions:

- Check for Impurities: Sources include misfolded populations, proteolysis, or cysteine oxidation [2] [6]. Ensure post-translational modifications are homogeneous [1].

- Enhance Stability: Add stabilizing ligands, cofactors, or substrates to the sample buffer. Use longer-lived reducing agents like TCEP (half-life >500 hours) instead of DTT to maintain protein stability over long crystallization periods [2] [6].

- Employ Fusion Strategies: Introduce stable structural domains (e.g., GST tags) or use antibody fragments (Fabs) as crystallization chaperones to facilitate ordered lattice formation [2] [5].

Problem 3: Rapid Precipitation Instead of Crystallization

- Potential Cause: Low sample solubility or aggregation.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: Identify the optimal buffer, salt, and pH using stability assays like differential scanning fluorimetry [2] [6]. Keep buffer components below ~25 mM and salt below 200 mM [2] [6].

- Increase Solubility: For recombinant proteins, test different affinity tags (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag) at either the N- or C-terminus to improve solubility [3]. The addition of charged amino acids like L-Arg can also prevent aggregation [3].

- Perform Pre-crystallization Test: Use a sparse-matrix approach to determine the ideal protein concentration, avoiding concentrations that lead to precipitation [2].

Experimental Protocols for Quality Control

Protocol 1: Assessing Sample Homogeneity with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Purpose: To determine the monodispersity and hydrodynamic radius of a protein sample, key indicators of homogeneity suitable for crystallization [4] [5].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze or dilute the protein into its final crystallization buffer. Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 15,000 x g) for 10 minutes to remove any dust or large aggregates.

- Instrument Calibration: Follow the manufacturer's instructions to calibrate the DLS instrument using a standard of known size.

- Data Acquisition: Load the clarified supernatant into a cuvette. Set the instrument to measure at a controlled temperature (typically 4°C or 20°C). Collect data for 5-10 acquisitions.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze the correlation function to obtain the size distribution.

- An ideal, homogenous sample will show a single, sharp peak.

- A polydispersity index (PdI) below 20% is generally acceptable for crystallization trials. A high PdI or multiple peaks indicates a heterogeneous sample that requires further optimization [4].

Protocol 2: Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutagenesis

Purpose: To reduce surface flexibility and create new crystal contact opportunities by replacing high-entropy residues with smaller, less flexible ones [5].

Procedure:

- In Silico Analysis: Use protein structure prediction software (e.g., AlphaFold3) or an existing homologous structure to identify surface-exposed, flexible residues, typically lysine (K) and glutamic acid (E) [2] [5].

- Residue Selection: Select clusters of 2-3 high-entropy residues for mutation. Design primers to mutate these residues to alanine (A), serine (S), or threon (T).

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Perform PCR-based mutagenesis to create the desired SER mutant constructs.

- Expression and Purification: Express and purify the mutant proteins as for the wild-type protein.

- Validation: Test the stability and activity of the mutants. Proceed with crystallization trials for stable mutants, which often have a higher propensity to form well-diffracting crystals.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Methods for Assessing Sample Quality

| Method | Parameter Measured | Ideal Outcome for Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE [1] | Protein purity and impurity detection | Single band at expected molecular weight, >95% purity. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) [2] [1] | Oligomeric state, sample homogeneity | Single, symmetric elution peak. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [2] [4] [5] | Hydrodynamic radius, monodispersity | Single, narrow peak; polydispersity index < 20%. |

| Static Light Scattering (SLS) [4] | Second viral coefficient (B22) | B22 value in range of -0.8x10⁻⁴ to -8x10⁻⁴ mol mL g⁻² [4]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy [1] | Protein's secondary structure | Spectrum indicative of folded, stable protein. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Reagent | Function in Purification/Homogenization |

|---|---|

| Affinity Tags (His-tag, GST-tag) [3] | Facilitates protein purification and can improve solubility; may act as crystallization chaperones. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) [2] [6] | A stable, odorless reducing agent with a long half-life across a wide pH range, preventing cysteine oxidation. |

| Chaotropic Agents (Urea, Guanidine HCl) [3] | Solubilize proteins from inclusion bodies; used at mild concentrations to refold proteins. |

| L-Arginine [3] | Additive that increases protein solubility and prevents aggregation during concentration and storage. |

| Glycerol [2] [6] | Cryoprotectant and stabilizing agent; should be kept below 5% (v/v) in final crystallization drops. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My protein is >95% pure by SDS-PAGE, but still won't crystallize. What else should I check? SDS-PAGE confirms chemical purity but not conformational homogeneity. Use DLS to check for monodispersity and SEC to verify a uniform oligomeric state. Also, consider using circular dichroism to confirm the protein is properly folded and stable [1] [4].

Q2: How does the choice of affinity tag impact crystallization? Affinity tags can influence solubility, stability, and even form crystal contacts. If one tag fails, try a different tag or switch its position (N- vs. C-terminal). In some cases, tag removal is necessary for successful crystallization [3].

Q3: What is the single most important factor for initial crystallization screening? While purity and homogeneity are critical, protein stability is paramount. Crystals can take days to months to nucleate. Use thermal shift assays to find buffer conditions, pH, and ligands that maximize your protein's stability before setting up crystallization trials [2] [6].

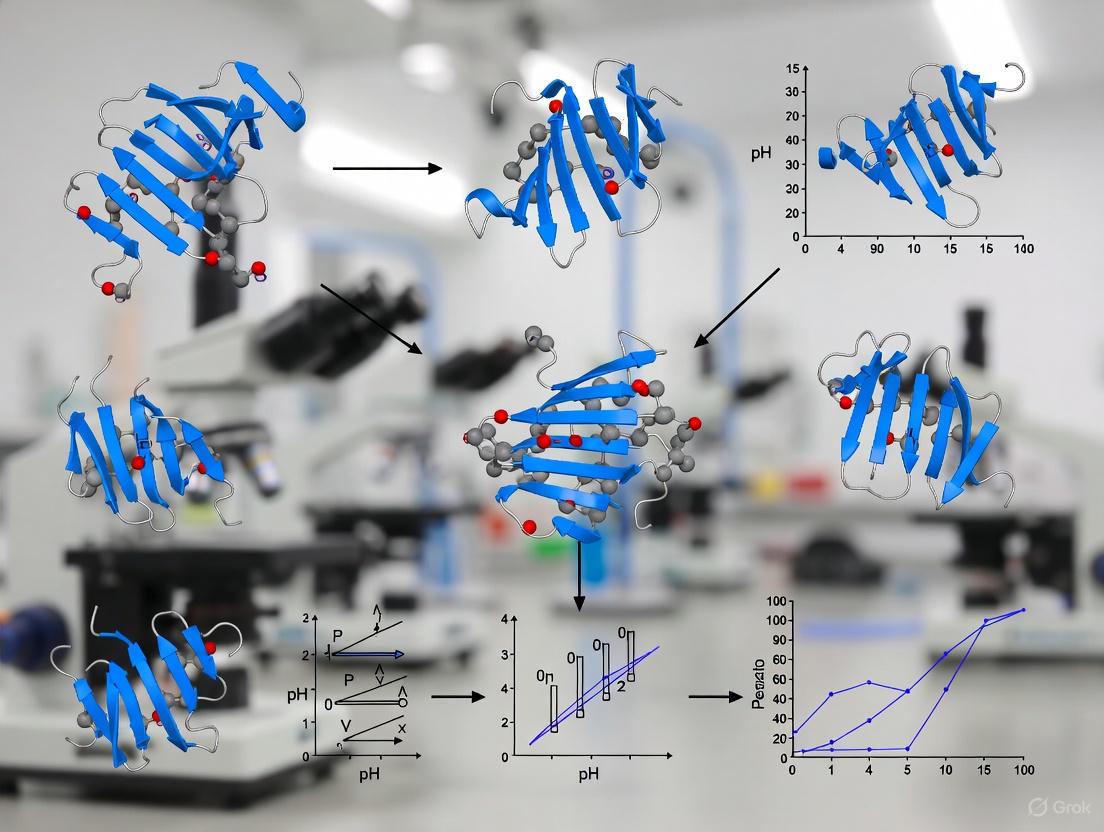

Workflow Diagram: From Protein to Crystal

The diagram below outlines the critical steps and quality control checkpoints for preparing a crystallization-ready sample.

Mastering the Protein Crystallization Phase Diagram

Protein crystallization is an indispensable yet often frustrating step in structural biology and drug development. A significant number of crystallization experiments fail to yield high-quality crystals, creating a major bottleneck. Within this context, the protein crystallization phase diagram emerges as a powerful conceptual and practical tool for diagnosing and correcting experimental failures. A phase diagram is a map that illustrates the state of a protein solution—soluble, metastable, crystalline, or precipitated—under different conditions, most commonly plotted as protein concentration against precipitant concentration [7] [8]. By understanding and utilizing this map, researchers can systematically move away from conditions that produce no crystals or poor-quality precipitates, and toward the narrow zone where well-ordered, diffraction-quality crystals grow. This guide is designed to transform the phase diagram from an abstract concept into a daily troubleshooting tool for scientists navigating the challenges of protein crystallization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What does a basic protein crystallization phase diagram look like and what do the zones mean?

A typical phase diagram, with precipitant concentration on the x-axis and protein concentration on the y-axis, is divided into several key zones that predict the outcome of your experiment [7] [9]:

- Undersaturated Zone (Soluble): Here, the protein concentration is below its solubility limit. The solution remains homogeneous, and crystals will not form or will dissolve if seeded [7].

- Metastable Zone: In this region, the solution is supersaturated, but the energy barrier for spontaneous nucleation is high. While new crystals will not readily form, existing seeds will grow. This zone is often ideal for producing large, well-ordered crystals because growth occurs slowly without being overwhelmed by excessive nucleation [9].

- Labile Zone (Nucleation): This area of high supersaturation is where spontaneous nucleation (the formation of new crystal nuclei) is favored. It often results in many small, potentially poorly formed crystals, or even a "shower" of microcrystals [9].

- Precipitation Zone: At very high concentrations of both protein and precipitant, the protein rapidly falls out of solution in a disordered, amorphous solid, which is unsuitable for X-ray crystallography [7] [9].

The boundary between the undersaturated and supersaturated zones is the solubility curve. The boundary between the metastable and labile zones is the supersolubility or nucleation curve [7].

FAQ 2: My crystallization trials only produce precipitate or "oils." How can the phase diagram help?

The formation of precipitate or amorphous liquid phases (oils) indicates your experiment is starting in or quickly moving through the labile zone directly into the precipitation zone [7] [10]. The phase diagram suggests several corrective strategies:

- Shift to the Metastable Zone: Your current protein and/or precipitant concentration is too high. Dilute your protein stock or use a lower concentration of precipitant to target the metastable zone.

- Use Microseeding: Since the metastable zone supports growth but not nucleation, you can introduce pre-formed crystal seeds into conditions within this zone. This is a highly effective method for obtaining single, large crystals from otherwise precipitating conditions [9].

- Improve Protein Solubility: "Oiling out" can signal poor protein-solvent interactions. Consider adjusting the buffer pH away from the protein's pI, or adding small polar additives like glycerol or ligands to enhance solubility and shift the phase boundaries [10].

FAQ 3: I see microcrystal showers, but no single large crystals. What is the issue according to the phase diagram?

A shower of microcrystals is a classic symptom of an experiment residing squarely in the labile (nucleation) zone [9]. The high supersaturation drives the formation of a vast number of nuclei, consuming the available protein before any single crystal can grow large. The solution is to lower the level of supersaturation to move your experiment into the metastable zone. This can be achieved by:

- Lowering Protein Concentration: Reduce the amount of protein in the drop.

- Fine-Tuning Precipitant Concentration: Slightly decrease the precipitant concentration.

- Using Cross-Seeding: A heavily diluted seed stock from the microcrystal shower can be introduced into a new drop with a lower precipitant concentration, effectively transferring a limited number of nucleation sites to the metastable zone for controlled growth.

FAQ 4: Nothing happens in my trials—no crystals, no precipitate. What does this mean?

If your drops remain clear indefinitely, the condition is almost certainly located in the undersaturated zone [7] [11]. The concentration of the protein has not reached the point where it is driven to come out of solution. To overcome this:

- Increase Supersaturation: Systematically increase the concentration of the precipitant or the protein in your trials.

- Promote Nucleation: If increasing concentration does not work, try techniques to induce nucleation, such as scratching the inside of the crystallization vessel with a micro-tool or adding a microscopic seed crystal (macroseeding) [11].

FAQ 5: My crystals are small and do not diffract well. How can phase diagram optimization help?

Poor diffraction often stems from internal disorder in the crystal, which can be caused by rapid, uncontrolled growth in the labile zone or the incorporation of impurities. The phase diagram guides you to grow crystals in the metastable zone, where slower growth favors the formation of highly ordered lattices [9]. Furthermore, techniques like controlled dehydration, informed by the phase diagram, can slowly increase precipitant concentration (moving horizontally on the diagram) to gently compress the crystal lattice and improve order and diffraction resolution [12].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: Constructing a Phase Diagram via Microbatch

Objective: To empirically determine the phase boundaries for your protein using the microbatch under oil method, which allows for precise control over the initial conditions [9].

Materials:

- Purified protein (>95% purity)

- Precipitant stock solution (e.g., PEG, salt)

- Crystallization plate compatible with microbatch (e.g., 96-well plate)

- Paraffin or silicone oil

Protocol:

- Design the Screen: Choose a single precipitant (e.g., PEG 4000) and a fixed buffer. Create a two-dimensional grid where you vary the precipitant concentration along one axis (e.g., 24 conditions from low to high) and the protein concentration along the other (e.g., 6 different concentrations) [9].

- Dispensing: For each protein concentration, dispense a series of drops under oil that combine a fixed volume of protein with a varying volume of precipitant solution, covering the entire range of precipitant concentrations.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Seal the plate and incubate it at a constant temperature. Monitor the drops regularly with a microscope over days and weeks.

- Scoring and Mapping: Record the outcome for each drop (Clear, Crystals, Precipitate, etc.). Plot these results on a graph of Protein Concentration vs. Precipitant Concentration.

- Draw Boundaries: Draw the approximate solubility curve along the points where the first crystals appear at each protein level. The supersolubility curve can be drawn through the points where microcrystal showers first occur.

Guide 2: Optimizing Crystals Using Microseeding

Objective: To use pre-formed microcrystals to nucleate growth in the metastable zone of the phase diagram, thereby producing larger, single crystals [9].

Materials:

- A source of crystals (even small or poor ones) from a previous trial

- Harvesting buffer (mother liquor from a stable condition)

- Seeding tools (e.g., microprobe, cat whisker)

- Crystallization plates (sitting drop or hanging drop)

Protocol:

- Identify Metastable Zone: From your phase diagram, identify a condition with a precipitant concentration that is clear or produces only a few crystals (i.e., near the solubility curve).

- Prepare Seed Stock: Transfer a single crystal to a small volume (e.g., 40 µL) of harvesting buffer. Gently crush the crystal using a micro-tool to create a suspension of microseeds [9].

- Dilute Seed Stock: Serially dilute the seed stock (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) in harvesting buffer. The optimal dilution is empirical and must be determined by testing.

- Set Up Seeded Trials: Prepare new crystallization drops with a precipitant concentration in the metastable zone. Introduce a very small volume (e.g., 0.1 - 0.3 µL) of a diluted seed stock into each drop.

- Incubate and Monitor: Seal the plate. With optimized seeding, you should observe the growth of one or a few large crystals within the metastable drop over the ensuing days.

Table 1: Common Crystallization Problems and Phase Diagram-Based Solutions

| Observed Problem | Diagnosed Phase Diagram Issue | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| No crystals, clear drop | Condition in Undersaturated Zone [7] [11] | Increase protein or precipitant concentration; use nucleation promotion (scratching, seeding) [11]. |

| Showers of microcrystals | Condition in Labile Zone [9] | Lower protein concentration; lower precipitant concentration; use seeding to transfer to metastable zone. |

| Amorphous precipitate or "oils" | Condition in Precipitation Zone [7] [10] | Reduce protein/precipitant concentration; alter pH; add solubility enhancers (e.g., glycerol) [10]. |

| Few, large, poorly-diffracting crystals | Condition may be in Metastable Zone, but with impurities or poor kinetics. | Improve protein purity and homogeneity; use crystal annealing or post-crystallization treatments like controlled dehydration [12]. |

| Irreproducible results | Uncontrolled nucleation near the labile-metastable boundary. | Use strict temperature control; employ seeding for reproducibility; switch to vapor diffusion if pH fluctuation is suspected (e.g., with volatile buffers) [9]. |

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Poor Diffraction with Post-Crystallization Treatments

Objective: To improve the diffraction quality of existing crystals by manipulating their hydration and order, a process that can be understood as a fine, controlled movement within the phase diagram.

Protocol:

- Harvesting: Carefully harvest a crystal in a small loop, together with a tiny amount of mother liquor.

- Controlled Dehydration:

- Prepare a series of reservoir solutions with incrementally higher precipitant concentrations (e.g., +2% to +5% PEG per step).

- Transfer the crystal in its loop to a stream of air or to a well containing one of the higher-concentration solutions for a short period (minutes to hours).

- Monitor the crystal for signs of cracking or dissolution. The goal is to slowly drive water out of the crystal lattice, compressing it and improving order [12].

- Testing: After treatment, flash-cool the crystal and test for diffraction. If successful, you will observe a higher resolution limit.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phase Diagram Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Phase Diagram Analysis | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A common precipitant that excludes protein from solution, driving phase separation. Available in a range of molecular weights. | Used as the precipitant axis in a phase diagram screen to induce crystallization and precipitation [9]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | A salt that competes for water molecules with the protein (salting out), reducing solubility. | Another common precipitant for defining the y-axis of a phase diagram. |

| Microbatch Plates & Oil | Allows for precise, stable dispensing of crystallization trials without concentration change via vapor diffusion. | Ideal for empirically determining a phase diagram because the initial condition is known and constant [9]. |

| Harvesting Buffer | A solution matching the mother liquor of a crystal, used to preserve crystal integrity during manipulation. | Used for creating seed stocks and for dilution during serial microseeding [9]. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., Glycerol, MPD) | Compounds that replace water to prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling. | While not for phase diagram construction, they are essential for preserving crystal quality for diffraction testing after phase diagram optimization. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Phase Diagram Troubleshooting Workflow. This flowchart provides a logical pathway for diagnosing common crystallization failures and selecting the appropriate phase diagram-based correction strategy.

A troubleshooting guide for resolving common protein crystallization failures.

Successful protein crystallization hinges on the precise control of biochemical parameters. This guide addresses frequent challenges related to pH, sample stability, and additives, providing targeted troubleshooting advice and practical solutions to help researchers obtain high-quality crystals.

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. My protein consistently precipitates instead of crystallizing. How can I adjust the biochemical conditions?

Consistent precipitation often indicates issues with sample homogeneity or the supersaturation level in your crystallization screen.

- Investigate Sample Purity and Stability: Ensure your protein is at least 95% pure and monodisperse (non-aggregating) [2]. Use methods like Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to check for aggregates [2] [13]. A homogeneous sample is crucial for an ordered crystal lattice.

- Optimize the Precipitant Type and Concentration: Precipitation can occur if the precipitant concentration drives the solution too deeply into the labile (unstable) region of the phase diagram. Systematically screen different precipitants:

- Fine-tune Protein Concentration: An overly concentrated protein sample can lead to uncontrolled precipitation. Use a pre-crystallization test (e.g., a sparse-matrix hanging-drop experiment) to determine the ideal concentration range for your protein [2].

2. How does pH specifically influence crystallization success, and how can I find the optimal pH?

pH profoundly affects a protein's electrostatic surface charges, which govern its solubility and its ability to form crystal contacts with other molecules [2] [15].

- Target the Isoelectric Point (pI): Proteins frequently crystallize within 1-2 pH units of their theoretical pI [2] [14]. As a rule of thumb:

- Employ a Dynamic pH Screening Strategy: Instead of only using fixed pH conditions, consider screens where the pH varies over the incubation time. This can act as an automatic search for the optimal crystallization pH [15].

- Choose Buffers Wisely: Use buffers like HEPES or Tris at concentrations of 10-50 mM [14]. Avoid phosphate buffers, as they can form insoluble salts [2].

3. What is the best way to maintain protein stability during long crystallization trials?

Crystals can take days or months to grow, making long-term stability essential [2].

- Use Appropriate Reducing Agents: If your protein has cysteine residues, use reducing agents to prevent oxidation. The choice of reductant is critical as their lifespans vary significantly [2].

| Reducing Agent | Typical Working Concentration | Solution Half-Life (at pH 8.5) | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | ~1-10 mM | ~1.5 hours | Requires replenishment in long trials [2]. |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | ~1-10 mM | >500 hours (pH 1.5-11.1) | Superior for long-term stability; stable across a wide pH range [2]. |

- Add Stabilizing Ligands and Substrates: Including a substrate, cofactor, or metal ion that your protein binds can lock it into a stable, homogeneous conformation [2].

- Control Temperature and Additives: Run crystallization trials at 4°C to slow down degradation. Stabilizing additives like glycerol (below 5% v/v) or sugars can also enhance stability [2] [14].

4. When and which additives should I use to improve crystal quality?

Additives are small molecules or ions that can improve crystal growth by enhancing order, mediating crystal contacts, or stabilizing the protein.

- Use Additives to Order Flexible Regions: If your protein has flexible loops or domains, additives like short-chained PEGs or MPD can help stabilize these regions [2].

- Promote Crystal Contacts: Divalent metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺) can act as bridges between protein molecules, facilitating the formation of the crystal lattice [14].

- Solubilize Ligands: For co-crystallization of protein-ligand complexes, use solubilizers like DMSO, surfactants, or cyclodextrins to keep hydrophobic ligands in solution [13].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Characterization Protocol

A rigorous pre-crystallization workflow is vital for diagnosing and preventing common problems.

Procedure:

- Initial Purification: Purify the protein using Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to obtain a homogenous sample. Coupling SEC with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) provides a robust assessment of molecular weight and monodispersity [13].

- Characterize Stability and Homogeneity:

- Final Sample Preparation:

Co-crystallization vs. Ligand Soaking Decision Guide

Choosing the right method for forming protein-ligand complexes is critical for successful structural determination.

Co-crystallization Protocol [13]:

- Incubate the protein with a 10 to 1000-fold molar excess of the ligand (relative to its Kd) in solution prior to crystallization.

- Set up crystallization trials with the pre-formed protein-ligand complex. This often requires condition optimization, as the ligand can alter the crystal packing.

- To accelerate co-crystallization, consider microseeding. This technique uses crushed microcrystals to bypass nucleation, directly promoting crystal growth in the metastable zone [13].

Ligand Soaking Protocol [13]:

- Grow high-quality "apo" (ligand-free) protein crystals.

- Prepare a soaking solution containing the ligand dissolved in the crystallization buffer or a stabilizing buffer. Use solubilizers like DMSO if needed.

- Transfer the crystal into the soaking solution for a duration ranging from seconds to days. Monitor the crystal closely, as soaking can sometimes crack the crystal due to ligand-induced conformational changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HEPES/Tris Buffer | Maintains solution pH. | Use at 10-50 mM; avoid phosphates to prevent insoluble salts [2] [14]. |

| TCEP | Reducing agent to prevent cysteine oxidation. | Chemically stable; ideal for long experiments unlike DTT [2]. |

| PEG (various MW) | Precipitant inducing macromolecular crowding. | High MW PEGs (e.g., PEG 8000) work by volume exclusion [2] [14]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Precipitant acting via "salting out". | A very common salt in crystallization screens [2]. |

| Glycerol | Stabilizing agent and cryoprotectant. | Keep below 5% (v/v) in crystallization drops [2]. |

| MPD | Additive and precipitant that binds hydrophobic patches. | Affects the protein's hydration shell [2]. |

| DMSO | Solubilizer for hydrophobic ligands. | Essential for co-crystallization and soaking experiments [13]. |

| Seed Beads | For microseeding to improve crystal growth. | Used to crush microcrystals for seeding [13]. |

How Interfaces and Heterogeneous Nucleants Influence Success

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my protein crystallization experiments often fail to produce any crystals? Failure to form crystals is often due to an inability to reliably overcome the initial nucleation barrier. In the metastable zone of a protein phase diagram, the solution is supersaturated but the energy barrier for nucleation is too high for crystals to form spontaneously. The absence of effective nucleating surfaces or agents in your setup can result in this common failure [16] [17].

FAQ 2: How can I increase the reproducibility of my protein crystallization trials? Employ controlled heterogeneous nucleants. The stochastic nature of nucleation can lead to poor reproducibility. Using engineered surfaces, porous materials, or specific nucleating agents provides consistent sites for crystal formation, standardizing the initial nucleation step and improving experimental consistency [16] [18].

FAQ 3: What can I do if my protein crystallizes but the crystals are too small for X-ray diffraction? This often occurs when nucleation is too rapid and widespread, depleting the protein solution and preventing large crystal growth. To address this, use nucleants that function at lower supersaturation or employ methods like gels that suppress convection. These approaches can reduce the number of nucleation sites and favor the growth of fewer, larger crystals [17] [18].

FAQ 4: Why does the presence of an oil overlay in vapor diffusion trials sometimes affect crystallization? The oil-water interface acts as a potent heterogeneous nucleant. Even seemingly inert interfaces like oil can dramatically alter local solute concentration. For instance, molecular dynamics simulations show glycine concentration is significantly enhanced at a tridecane-water interface, facilitating nucleation. The nature of the interface in your setup is a critical, often overlooked, variable [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: No Crystal Formation

Issue: Despite high supersaturation, no crystals appear after extensive incubation. Explanation: The system may be stuck in a metastable state where the energy barrier for homogeneous nucleation cannot be overcome. Solution: Introduce targeted heterogeneous nucleants.

- Step 1: Identify potential nucleants based on your protein's characteristics (e.g., charge, hydrophobicity).

- Step 2: Test a panel of nucleants. Start with versatile options like porous materials (e.g., bioglass, porous silicon) or functionalized nanoparticles.

- Step 3: Implement the nucleant in your crystallization setup (e.g., vapor diffusion, batch).

- Expected Outcome: Nucleants lower the free energy barrier ((\Delta G{het}^*)) for nucleation according to the relationship (\Delta G{het}^* = f(c) \cdot \Delta G_{hom}^*), where the potency factor (f(c)) is less than 1, making nucleation in the metastable zone possible [16] [17] [20].

Problem 2: Excessive, Microscopic Crystals

Issue: Many tiny crystals form, but none are of sufficient size for data collection. Explanation: An excessive number of nucleation events deplete the protein from the solution, starving crystal growth. Solution: Reduce the number of nucleation sites and control the nucleation rate.

- Step 1: Shift to a lower supersaturation level in the phase diagram, where nucleation is less spontaneous.

- Step 2: Use nucleants with lower "potency" or reduce their surface area in contact with the solution.

- Step 3: For proteins prone to this issue, consider crystallization in a gel matrix (e.g., agarose). The gel suppresses convection and turbulent flows, creating a diffusion-dominated environment that can lead to more orderly growth and fewer nuclei [16] [17].

- Expected Outcome: A lower density of nucleation events, allowing fewer crystals to grow larger by consuming the available protein.

Problem 3: Poor Crystal Quality or Polymorph Control

Issue: Crystals form but are poorly ordered, show multiple morphologies, or are the wrong polymorph for drug formulation. Explanation: Uncontrolled nucleation can lead to disorder, and different interfaces may favor different crystal forms or polymorphs. Solution: Exploit interface-specific templating for polymorph selection.

- Step 1: Select nucleants known to template the desired polymorph. The chemical functionality and topography of the surface can dictate the crystalline structure that forms on it.

- Step 2: For porous nucleants, the pore size is critical. A synergistic diffusion-adsorption effect inside sufficiently narrow pores (e.g., < 1 µm for proteins) increases local protein concentration, facilitating the initial formation of a stable 2D crystalline layer on the pore wall [18].

- Step 3: Characterize the first crystals that form to confirm the polymorph.

- Expected Outcome: Improved crystal uniformity and selection of the therapeutically relevant polymorph through directed nucleation.

Problem 4: Inconsistent Results Between Different Experimental Setups

Issue: Crystallization succeeds in microbatch under oil but fails in hanging drop setups, or vice versa. Explanation: Different interfaces present in each setup (e.g., air-water vs. oil-water) have distinct effects on local protein concentration and nucleation. Solution: Acknowledge and standardize the interface environment.

- Step 1: Understand that air-water interfaces often deplete hydrophilic proteins, while oil-water interfaces may concentrate them, as demonstrated with glycine [19].

- Step 2: For small-volume experiments where interfaces dominate, consistently use the same type of oil or surface material.

- Step 3: If transferring conditions from one platform to another, re-optimize with the specific interfacial properties of the new platform in mind.

- Expected Outcome: Greater reproducibility by controlling for the variable of interfacial chemistry.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The table below summarizes key materials used to control nucleation in protein crystallization experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Mechanism | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Porous Materials (e.g., Bioglass, Porous Silicon, Zeolites) | Confinement in pores creates a diffusion-adsorption effect, increasing local protein concentration to critical levels for nucleation [18]. | Inducing nucleation for refractory proteins; improving crystal diffraction quality [18]. |

| Functionalized Nanoparticles (e.g., Nanodiamond, Gold NPs) | Large surface area reduces nucleation barrier; surface chemistry can be tailored for specific protein interactions [17]. | General promotion of nucleation for various proteins; controlling crystal size and number [17]. |

| Short Peptide Hydrogels | 3D fibrillar network acts as a non-convective medium that can stereochemically interact with proteins, stabilizing nascent crystals [17]. | Growing high-quality crystals for X-ray diffraction; stabilizing insulin crystals for drug delivery [17]. |

| DNA Origami/Structures | Programmable scaffolds provide precisely ordered, specific binding sites to template and orient protein nucleation [17]. | Crystallizing proteins at low concentration; controlling crystal orientation [17]. |

| Natural Nucleants (e.g., Horse Hair, Mineral Powders, Seaweed) | Surface microstructures and chemical properties provide diverse nucleation sites, though their action can be protein-specific [17]. | Low-cost, initial screening for difficult-to-crystallize proteins [17]. |

| Engineered Surfaces (e.g., Self-Assembled Monolayers - SAMs) | Chemically defined surfaces with specific functional groups (e.g., COOH, NH2) to control protein-surface interactions and templating [16]. | Fundamental studies of heterogeneous nucleation; reproducible surface-induced nucleation [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing a Porous Nucleant

Objective: To induce nucleation and grow high-quality crystals of a target protein using a porous nucleant material.

Materials:

- Purified target protein solution.

- Crystallization buffer/precipitant solution.

- Porous nucleant (e.g., crushed Bioglass, porous silicon chip).

- Crystallization plate (for sitting drop vapor diffusion).

- Microscope for visualization.

Procedure:

- Prepare Crystallization Plates: Set up a standard sitting drop vapor diffusion plate with reservoir solution.

- Apply Nucleant: Place a small, sterile piece of the porous nucleant material (e.g., ~100 µm chip) into the sitting drop well before adding the protein-precipitant mix.

- Mix and Incubate: Pipette a mixture of protein solution and reservoir solution onto the nucleant in the sitting drop well. Seal the plate and incubate at the appropriate temperature.

- Monitor and Harvest: Check the drops daily under a microscope. Crystals may nucleate within the pores or on the surface of the nucleant. Once crystals reach the desired size, harvest them carefully for analysis.

Mechanism Visualization: The diagram below illustrates the molecular-kinetic mechanism of protein crystal nucleation within a porous material.

Protein Nucleation in a Pore

Experimental Protocol: Testing Oil-Water Interface Effects

Objective: To systematically evaluate the effect of an oil-water interface on the nucleation rate of a model protein (e.g., Lysozyme).

Materials:

- Lysozyme powder.

- Sodium acetate buffer.

- NaCl precipitant.

- High-purity oil (e.g., Tridecane).

- Glass vials (e.g., 1.5 mL).

- Precision temperature-controlled platform/incubator.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a lysozyme solution in sodium acetate buffer at a target concentration known to be in the metastable zone (e.g., 30 mg/mL).

- Sample Setup:

- Test Group: Pipette 1 mL of protein solution into a clean glass vial. Carefully overlay with 200 µL of tridecane.

- Control Group: Pipette 1 mL of protein solution into a vial without an oil overlay.

- Induction Time Measurement:

- Equilibrate all vials at a temperature that ensures full dissolution.

- Cool the vials at a controlled rate (e.g., 1.5 K/min) to the target crystallization temperature.

- Transfer to a temperature-stable incubator and use automated imaging (e.g., webcam) to capture images of the vials every 5 minutes.

- Record the induction time for each vial as the time elapsed from reaching the final temperature until the first crystal is detected.

- Data Analysis: Compare the mean induction times and nucleation rates between the test and control groups. A significantly shorter induction time in the test group indicates facilitated nucleation at the oil-water interface [19].

Systematic Screening and Advanced Crystallization Techniques

Protein crystallization remains a significant bottleneck in structural biology and drug development. The journey from a purified protein sample to a diffraction-quality crystal is often fraught with failures, from initial amorphous precipitation to the growth of crystals with poor diffraction properties. This technical support center is designed to help researchers navigate the three primary crystallization methods—Vapor Diffusion, Batch, and Microfluidics—by providing targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs. The content is framed within the broader context of academic thesis research aimed at systematically diagnosing and overcoming common protein crystallization failures, thereby enhancing the efficiency of structural determination pipelines.

Method Comparison and Selection Guide

The choice of crystallization method can significantly influence the success rate, especially when dealing with challenging proteins. The following table provides a comparative overview to guide your selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Crystallization Methods

| Feature | Vapor Diffusion | Batch (Microbatch) | Microfluidics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Equilibration of a drop against a larger reservoir via vapor phase [21] | All components mixed at set concentration under oil; no evaporation [22] | Free-interface diffusion or nanoliter-batch within microchannels [21] [23] |

| Typical Sample Volume | 0.5 - 1 µL [23] | 1 µL (microbatch) [22] | Picoliters to Nanoliters (10 nL reactions demonstrated) [23] |

| Sample Consumption | Milligrams for full screening [23] | Lower than standard vapor diffusion | 2 orders of magnitude less than conventional techniques [23] |

| Key Advantages | Well-established, high-throughput screening kits available | Simple setup, no concentration change, protects from contaminants [22] | Ultra-low sample use, superior kinetics, high success rate per condition [21] [24] [23] |

| Common Failure Modes | Over-concentration leading to precipitation; poor kinetic control | Limited exploration of concentration space | Susceptibility to air bubbles; device priming challenges [25] [23] |

| Best For | Initial screening of a wide range of conditions with ample protein | Optimization of known conditions; proteins sensitive to concentration changes | Precious protein samples (e.g., membrane proteins); difficult-to-crystallize targets [21] [23] |

The following decision pathway can help you select an appropriate method based on your protein and project constraints:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My vapor diffusion experiments consistently result in precipitate instead of crystals. What should I do?

This is a common issue where the protein is supersaturating too quickly, leading to chaotic aggregation rather than ordered crystal growth.

- Solution A: Fine-tune kinetics. Use microfluidic free-interface diffusion. This method allows for a slow, controlled diffusive mixing of the protein and precipitant solutions, which can promote the growth of high-quality crystals by exploring a wider range of concentration gradients within a single experiment [21].

- Solution B: Switch to Microbatch. Crystallizing under a paraffin oil (which prevents evaporation) allows you to maintain a constant concentration, avoiding the potentially detrimental concentration kinetics of vapor diffusion [22]. This is ideal for proteins that are sensitive to gradual concentration changes.

- Solution C: Optimize your sample. Ensure your protein is pure and monodisperse. While high purity (>95%) is often recommended, note that the Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP) method, often implemented in microfluidic formats, has been shown to be more robust and can tolerate higher levels of impurities like extraneous proteins or lipids [26].

FAQ 2: I have a very limited amount of protein. How can I screen the most conditions?

Traditional vapor diffusion and batch methods can consume milligram quantities of protein for a comprehensive screen, which is often impractical.

- Solution: Employ microfluidics. Microfluidic chips are designed specifically for this scenario. They can perform hundreds of crystallization trials using orders of magnitude less protein than conventional techniques. For example, one documented chip uses only 10 nL of protein per condition, allowing 144 parallel reactions from a single, small protein sample [23].

FAQ 3: Air bubbles are clogging my microfluidic device and ruining my experiments. How can I prevent this?

Air bubbles are among the most recurring and detrimental issues in microfluidics, causing flow instability, increased resistance, and experimental artifacts [25].

- Preventive Measures:

- Chip Design: Avoid acute angles in your microfluidic channel design to reduce the risk of bubbles adhering.

- Degassing: Degas all your buffers and protein solutions prior to the experiment, especially if they will be heated.

- Leak-free Fittings: Ensure all fittings are tight. Using Teflon tape on threads can help create a perfect seal [25].

- Corrective Measures:

- Pressure Pulses: If using a pressure controller, apply rapid pressure pulses. This can help detach bubbles from channel walls.

- Increase Pressure: Temporarily increasing the system pressure can help dislodge and flush out trapped bubbles.

- Bubble Traps: Integrate a commercial or custom-fabricated bubble trap into your fluidic setup upstream of the chip [25].

FAQ 4: Is the Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP) method more tolerant of impurities?

Yes, studies have shown that LCP-based crystallization is remarkably robust in the face of common impurities. Crystals of the photosynthetic reaction center were obtained from samples with substantial levels of contamination, including up to 50% protein impurities and added lipid material or membrane fragments [26]. This suggests that for initial crystallization screening of difficult-to-purify membrane proteins, the LCP method (often executed using microfluidic devices) may avoid the need for ultra-high purity samples.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microbatch Crystallization under Oil

This protocol is adapted for screening initial conditions using a modified microbatch (microbatch diffusion) method [22].

- Prepare the Plate: Dispense 40-100 µL of a 1:1 mixture of silicone fluid and paraffin oil (e.g., Al's Oil from Hampton Research) into each well of a standard 96-well plate. This oil mixture allows for controlled water evaporation, concentrating the drop over time.

- Dispense the Drop: Using a pipette, dispense a 1 µL drop of your purified protein solution directly into the oil. The drop will sink to the bottom of the well.

- Add Precipitant: Dispense a 1 µL drop of the crystallization screening condition solution into the same well, allowing it to sink and coalesce with the protein drop.

- Incubate and Observe: Seal the plate to prevent oil evaporation and contamination. Incubate at the desired temperature and observe the drop regularly for crystal growth under a microscope.

Protocol 2: Crystallization via Microfluidic Free-Interface Diffusion (Crystal Former)

This protocol summarizes the use of a commercial microfluidic device for screening [21].

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate your protein to a relatively high concentration (e.g., 10-114 mg/mL). Ensure the sample is in a suitable buffer and is centrifuged to remove any aggregates.

- Load the Device:

- Pipette 0.5 µL of your protein sample into one inlet of the device's microchannels.

- Pipette 0.5 µL of each precipitant condition from your screening kit (e.g., Smart Screen, PurePEGs) into the corresponding inlets on the other side of the channels.

- Seal and Incubate: Seal the channel inlets with the provided tape. Leave the tray at a stable temperature (e.g., room temperature) for crystallization to occur. The device will create a gradient of conditions via diffusion between the protein and precipitant solutions.

- Harvesting Crystals:

- Once a crystal is identified, use a razor blade to carefully cut the peelable film at the bottom of the tray surrounding the reaction chamber.

- Peel back the film and immediately apply a suitable cryoprotectant to prevent dehydration.

- Use a cryo-loop to harvest the crystal directly from the open chamber for X-ray diffraction testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Protein Crystallization Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Former | A commercial microfluidic device that utilizes liquid-liquid diffusion in 96 parallel channels [21]. | Initial screening and optimization of difficult proteins with minimal sample consumption. |

| PDMS Elastomer | A silicone polymer used to fabricate flexible, gas-permeable, and optically transparent microfluidic chips [27] [23]. | Creating custom or multi-layer microfluidic devices for crystallization. |

| Silicone/Paraffin Oil Mix | A 1:1 mixture that allows controlled water diffusion in microbatch experiments, slowly concentrating the crystallization drop [22]. | Modified microbatch screening for conditions that require slow kinetics. |

| PurePEGs Screen | A crystallization screen that samples the PEG precipitant space in a complex way with varying molecular weights [21]. | Identifying crystallization conditions that benefit from overlapping PEG gradients. |

| Monoolein | A lipid used to form the Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP) matrix for membrane protein crystallization [26]. | Crystallizing membrane proteins in a native-like lipid environment. |

Leveraging High-Throughput Screening and Laboratory Robotics

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Protein Crystallization Failures in an Automated Workflow

Problem: Failure to Grow Any Crystals

- Potential Cause 1: Insufficient Protein Purity or Homogeneity

- Solution: Re-optimize your purification protocol to achieve >95% purity. Employ multi-step chromatography and use dynamic light scattering (DLS) to confirm monodispersity and detect aggregates before setting up crystallization trials [28].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate Crystallization Condition Screening

- Solution: Leverage your HTS system to perform sparse-matrix screening. Utilize historical crystallization data to design a comprehensive condition library that systematically tests a wide range of pH, salts, and precipitants [28].

- Potential Cause 3: Rapid Crystallization Leading to Microcrystals

- Solution: If crystals form too quickly, they may incorporate impurities. Program the liquid handler to add a slightly larger volume of solvent to slow down the crystallization process, promoting the growth of larger, single crystals [11].

Problem: Growing Crystals That Do Not Diffract Well

- Potential Cause 1: Crystal Disorder or Twinning

- Potential Cause 2: Radiation Damage During Data Collection

- Solution: Implement cryo-cooling procedures universally. Ensure crystals are flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen before data collection. For highly sensitive samples, consider using smaller crystals and serial crystallography approaches to mitigate damage [28].

Problem: Membrane Protein Crystallization Failures

- Potential Cause: Instability in Detergent Micelles

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Robotic HTS Platform Performance

Problem: Low Z'-Factor or High Data Variability in Assays

- Potential Cause 1: Liquid Handling Inaccuracy

- Solution: Perform regular calibration and maintenance of pipetting heads. For sub-microliter dispensing, ensure the system is using low-dead-volume tips and that fluidics are free of air bubbles or obstructions [31].

- Potential Cause 2: Inconsistent Environmental Control

- Solution: Verify the temperature and CO₂ uniformity across all incubators using independent data loggers. Schedule assays to avoid frequent door openings that cause fluctuations [32].

Problem: System Integration Failures and Bottlenecks

- Potential Cause: Incompatibility Between Legacy Instruments and New Robotics

Problem: Sample Misidentification or Data Tracking Errors

- Potential Cause: Manual Transcription or Barcode Reading Failures

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our laboratory is new to HTS. What is the most critical factor for a successful screening campaign for protein crystallization? The most critical factor is assay robustness before automation. A robust crystallization trial is characterized by a high Z'-factor (typically >0.5), which indicates a wide separation between positive and negative control signals and low variability. Without this, an automated screen will efficiently generate unreliable data [31].

FAQ 2: How can we minimize human error in our automated crystallization workflow? Human error is best minimized by leveraging automation and software integration:

- Use automated liquid handlers to eliminate pipetting inaccuracies [33] [34].

- Implement workflow management software that guides technicians through manual steps and adds checkpoints to ensure protocols are followed completely [33].

- Establish a non-punitive error reporting culture so that mistakes can be analyzed and processes improved proactively [34].

FAQ 3: We keep getting crystalline "showers" instead of single crystals. How can robotics help? Robotics enable microseed matrix screening (MMS), a powerful technique to address this. Your automated system can be programmed to crush initial microcrystals to create a seed stock. It then systematically introduces these seeds into new crystallization conditions at lower supersaturation, guiding the growth of larger, single crystals instead of uncontrolled nucleation [28].

FAQ 4: What should we do if our robotic platform suddenly stops with a plate jam? First, follow your Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for system errors, which should prioritize safe system shutdown. After securing the environment, manually clear the obstruction. Use the event logs from the scheduling software to diagnose the root cause, which is often a communication timeout or a misaligned plate stacker. Document the incident and resolution for future reference [31] [34].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Automation on Laboratory Error Reduction

| Type of Laboratory Error | Manual Process Error Rate | With Automation Implementation | Error Reduction | Key Enabling Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-analytical Errors (e.g., sample ID, handling) | 46-68.2% of all errors [33] | Not explicitly quantified | Estimated >90% [33] | LIMS Integration, Barcode Tracking [33] [34] |

| Liquid Handling / Pipetting Inaccuracies | High variability [31] | Sub-microliter precision [31] | ~95% reduction in error rates [33] | Automated Liquid Handlers [33] [31] |

| Analytical Phase Errors (e.g., sample mix-up) | 7-13.3% of all errors [33] | Not explicitly quantified | Significant reduction | Workflow Scheduling Software [33] |

| Data Transcription Errors | Common [34] | Near elimination [34] | 90-98% decrease in error opportunities [33] | Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs), Direct Data Capture [34] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Crystallization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Crystallization | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Monoolein-rich Lipid Mixtures | Forms the lipidic cubic phase (LCP) matrix to stabilize membrane proteins for crystallization [28] [30]. | Essential for crystallizing G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and other integral membrane proteins. |

| Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutants | Protein engineering strategy where high-entropy surface residues (Lys, Glu) are mutated to Ala/Ser to facilitate crystal contacts [28]. | Used for proteins with flexible surface regions that prevent stable lattice formation. |

| Selenium-substituted Methionine (Se-Met) | Provides heavy atoms for experimental phasing via Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD/MAD) [28]. | Requires expression in defined media; contributes to over 70% of de novo structures. |

| Microseeding Stock | A suspension of crushed microcrystals used to nucleate growth in new conditions via Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS) [28]. | Solved problem of crystalline showers; allows growth of larger, single crystals. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., Glycerol, PEG) | Displaces water to prevent ice formation during flash-cooling of crystals prior to X-ray data collection [28]. | Standard procedure for almost all macromolecular crystals to mitigate radiation damage. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Sparse-Matrix Screening for Initial Crystallization Hits

Purpose: To efficiently identify initial crystallization conditions for a purified protein using an automated platform. Materials: Purified protein (>95% purity), sparse-matrix screening kits (e.g., from Hampton Research or Jena Bioscience), 96-well or 384-well crystallization plates, automated liquid handler with nanoliter dispensing capability, plate sealer, plate hotel incubator.

Methodology:

- Plate Preparation: Program the liquid handler to dispense ~50-100 nL of each crystallization condition from the screening kits into the wells of the crystallization plate.

- Protein Dispensing: In a separate step, dispense an equal volume (50-100 nL) of your purified protein solution into each well containing condition.

- Sealing and Incubation: Automatically seal the plate with a transparent seal and transfer it to a temperature-controlled incubator (e.g., 20°C).

- Imaging and Analysis: Use an automated imaging system to periodically photograph each well over days to weeks. Integrate with AI-driven image analysis software (e.g., convolutional neural networks) to automatically identify and classify crystal growth [28].

Protocol 2: Automated Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS) to Optimize Crystal Quality

Purpose: To use microseeds from initial crystals to improve crystal size and diffraction quality across a broader range of conditions. Materials: A well containing initial microcrystals, seed bead (e.g., a small plastic or metal bead), MMS stock solution (precipitant solution), destination crystallization plate with new conditions, automated liquid handler.

Methodology:

- Seed Stock Preparation:

- Automatically transfer the well solution containing microcrystals and a seed bead to a sealed microtube.

- Agitate the tube in a plate shaker to crush the crystals into a microseed stock.

- Serially dilute the stock in MMS solution to create a range of seed concentrations [28].

- Setting up MMS Trials:

- Program the liquid handler to set up new crystallization drops as in Protocol 1.

- Immediately after setting up the drop, inject a small volume (e.g., 1-2 nL) of the diluted seed stock into each new drop.

- Incubation and Analysis: Seal, incubate, and image the plates as before. The presence of seeds promotes growth at lower supersaturation, often leading to fewer, larger, and higher-quality crystals.

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Diagram 1: HTS Crystallization Workflow

Diagram 2: Automated Error Reduction Logic

Exploiting Interfaces and External Fields for Nucleation Control

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical sample-related factors that prevent nucleation? The most critical factors are insufficient protein purity and poor conformational homogeneity. Protein samples with purity below 95% or those containing aggregates and charge heterogeneity significantly disrupt the ordered lattice formation required for nucleation. Furthermore, proteins with highly flexible surface regions or dynamic loops often fail to form stable crystal contacts. Techniques such as multi-step chromatography and dynamic light scattering (DLS) for monitoring monodispersity are essential for mitigation [35].

FAQ 2: How can I control nucleation when my protein only forms microcrystals or showers of needles? This is typically a result of excessively high nucleation density. To gain control, you should aim to reduce the supersaturation level by lowering the protein or precipitant concentration. A highly effective strategy is seeding, which involves using pre-formed microcrystals or crystal fragments (seeds) to induce growth in a separate, pre-equilibrated solution at a lower supersaturation. This provides controlled nucleation sites and promotes the growth of larger, single crystals [36].

FAQ 3: Can external fields really improve crystal quality, and which is most effective? Yes, external fields, particularly electric fields, have been demonstrated to improve crystal quality by controlling nucleation location, rate, and crystal morphology. Electric fields can order protein molecules, reduce the energy barrier for nucleation, and allow crystallization at lower supersaturation levels. The most significant parameters are field strength, frequency (AC or DC), and distribution. While both AC and DC fields are effective, AC fields with specific frequencies (e.g., 1 kHz) have shown promising results in controlling crystal morphology and expanding the crystallization region in phase diagrams [37] [38].

FAQ 4: What does "exploiting interfaces" mean in the context of protein nucleation? It involves using solid surfaces, liquid-air interfaces, or functionalized materials to promote and control the nucleation event. Interfaces can lower the energetic barrier for nucleation compared to homogeneous nucleation in the bulk solution. By tailoring the properties of these surfaces (e.g., with specific chemical functional groups or nanomaterials), you can attract protein molecules, increase local supersaturation, and even template the crystal lattice, leading to more reproducible nucleation and better-defined crystal attributes like size and habit [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Poor Crystal Morphology

Problem: Crystals grow as thin plates, needles, or clusters (sea urchins) instead of well-formed three-dimensional crystals.

| Problem Observation | Likely Cause | Solution Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Thin Plates | Anisotropic growth; favored growth in two dimensions. | Use additive screening to find compounds that alter surface energy. Optimize conditions to grow thicker crystals via seeding [36]. |

| Needles/Sea Urchins | Extremely high nucleation rate; kinetic trapping. | Reduce supersaturation (lower protein/precipitant). Smash needle clusters to create a seed stock for microseeding into fresh, less saturated drops [36]. |

| Dendritic "Christmas Tree" Growth | Rapid, diffusion-limited growth. | Use the dendritic crystals as seeds in new, optimized crystallization trials [36]. |

| Lattice Strain & Cracking | Accumulation of impurities or heterogeneous proteins in the crystal lattice. | Filter all solutions (0.22 µm). Re-check protein purity via gel electrophoresis and improve purification if needed [36]. |

Guide: Optimizing Experimental Parameters for External Fields

Application of Electric Fields: The table below summarizes key parameters for implementing electric field-induced nucleation control, based on recent research.

Table 1: Experimental Parameters for Electric Field-Induced Crystallization

| Parameter | Typical Range / Type | Impact & Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Field Type | AC (Alternating Current) | Reduces electrolysis; can alter protein-protein interaction potentials. Effective at low voltages (~1V) [37] [38]. |

| DC (Direct Current) | Causes protein migration to electrodes, creating local supersaturation. Requires careful management of pH changes [37]. | |

| Frequency | 1 kHz - 1 MHz | Lower frequencies (e.g., 1 kHz) in AC fields have been shown to significantly shift phase boundaries and alter crystal morphology [38]. |

| Field Strength | 1 V - 10 kV (context-dependent) | Low-voltage (~1 V) internal fields are effective and practical. High-voltage (1-10 kV) external fields are also used but require more complex setups [37]. |

| Electrode Material | Indium-Tin Oxide (ITO) | Optically transparent, allowing for in-situ monitoring of crystallization under a microscope [38]. |

| Sample Condition | Supersaturated solution | The field is applied to a solution that is already in a metastable or nucleation zone. It expands the operable crystallization region to lower supersaturations [37]. |

Experimental Protocol for Electric Field Application:

- Setup Preparation: Use a custom cell with ITO-coated glass electrodes, separated by a small gap (e.g., 160 µm) to minimize heating.

- Sample Loading: Prepare a supersaturated lysozyme solution (e.g., in acetate buffer with NaSCN) and load it into the cell.

- Field Application: Apply an AC electric field with a function generator. A typical starting point is a peak-to-peak voltage (Vpp) of 1.0 V and a frequency of 1 kHz.

- Monitoring: Observe crystal nucleation and growth in real-time using an inverted polarized-light microscope.

- Analysis: Compare the crystal morphology, number, and size with control experiments performed without an electric field [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Interface and Field-Based Nucleation Control

| Reagent / Material | Function in Nucleation Control |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Nanoparticles/Surfaces | Act as heteronucleants with tailored surface chemistry to absorb proteins, increase local concentration, and template crystal lattice formation [16]. |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Provides a membrane-like matrix for crystallizing membrane proteins, stabilizing them and facilitating lattice contacts [35]. |

| Seeding Stock (Microseeds) | A suspension of crushed microcrystals used to transfer nucleation sites into new drops, bypassing the stochastic nucleation step and promoting controlled growth [36]. |

| Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutants | Engineered proteins where high-entropy surface residues (Lys, Glu) are replaced with Ala or Thr to create more ordered surfaces, enhancing crystal contacts [35]. |

| Sodium Thiocyanate (NaSCN) | A precipitant salt whose anions (SCN⁻) bind strongly to protein surfaces (e.g., lysozyme), effectively tuning protein-protein interactions and promoting specific crystal forms [38]. |

| Indium-Tin Oxide (ITO) Electrodes | Provide optically transparent, conductive surfaces for applying electric fields while allowing direct visual monitoring of the crystallization process [38]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Electric Field Control

Diagram 1: Workflow for applying an electric field to control protein crystallization. This iterative process involves applying a field to a supersaturated solution and optimizing parameters based on real-time microscopic observation.

Logical Pathway for Nucleation Control Strategies

Diagram 2: Logical decision pathway for selecting nucleation control strategies. Based on initial experimental failures, researchers can choose to exploit interfaces or apply external fields, each with distinct tactical approaches.

Practical Guide to Common Precipitants and Additives

FAQs on Precipitants and Additives

What is the primary function of a precipitant in protein crystallization?

Precipitants work by reducing the solubility of the protein in solution, thereby creating a supersaturated state which is essential for initiating nucleation and subsequent crystal growth [39]. They achieve this by excluding water molecules, competing for solvent, or altering the structure of the water surrounding the protein, which encourages protein molecules to come together and form ordered crystals.

My protein solution remains clear with no precipitation or crystals. What should I do?

This indicates that your solution is undersaturated. You should systematically adjust your conditions to reach the supersaturation zone.

- Increase Protein Concentration: Ensure your protein is concentrated enough (typically 2-50 mg/mL for initial trials) [40] [10].

- Increase Precipitant Concentration: Gradually increase the concentration of your precipitant. A pre-screen kit can help determine if your protein concentration is suitable [10].

- Screen More Broadly: Employ sparse-matrix screening to explore a wide range of different precipitants, salts, and pH conditions, as the optimal combination is protein-specific [41] [40].

My experiments only yield amorphous precipitate or "oils." How can I promote crystal formation?

Amorphous precipitate often results from too rapid an approach to supersaturation, causing proteins to aggregate disorderly.

- Slow Down Equilibration: Use vapor diffusion methods, which allow for a gradual increase in supersaturation, over batch methods [40] [39].

- Reduce Concentrations: Lower the starting concentrations of both the protein and the precipitant in your crystallization drop.

- Use Additives: Incorporate additives like small polar organic molecules (e.g., glycerol, sucrose) to improve protein solubility and dissolve protein "oils" [10].

I only get thin needles or plates. How can I improve crystal morphology for better diffraction?

Poor crystal morphology often stems from high nucleation rates or specific impurities.

- Reduce Nucleation: Lower the protein or precipitant concentration to produce fewer nucleation sites, leading to larger, single crystals [36].

- Seeding: Use microseed matrix screening (MMS) by crushing these needles or plates to create a seed stock. Introducing these microseeds into new, slightly undersaturated solutions can promote the growth of larger, well-formed crystals [41] [36].

- Additive Screens: Implement an additive screen. Small molecules, ions, or ligands can bind to the protein surface and alter crystal packing to form more three-dimensional crystals [36].

Can combining different types of precipitants be beneficial?

Yes. Research has demonstrated that combining mechanistically distinct precipitants (e.g., a salt with an organic solvent) can synergistically enhance both the probability of crystallization and the quality of the resulting crystals. These mixtures can create unique lattice interactions, such as combined hydrophobic and electrostatic contacts, that single precipitants cannot [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Recurrent Amorphous Precipitate

Symptoms: Brown, shapeless matter in the crystallization drop with no distinct geometry [40].

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Protein Impurity | Re-purify protein to high homogeneity (>95%). Check purity via SDS-PAGE and monodispersity via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [29] [41]. |

| Rapid Supersaturation | Switch to a slower vapor diffusion method (hanging or sitting drop) from batch. Increase the reservoir-to-drop volume ratio to slow equilibration [40]. |

| Protein Instability | Add stabilizing ligands, cofactors, or inhibitors. Change buffer pH to be further from the protein's pI to increase solubility [10]. |

Problem 2: Too Many, Too Small Crystals (Microcrystals)

Symptoms: Hundreds of tiny crystals or a "shower" of microcrystals in the drop.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Excessive Nucleation | Reduce protein and/or precipitant concentration. Use seeding to control nucleation in undersaturated conditions [41] [36]. |

| High Kinetic Energy | Ensure crystallization trays are placed on a stable, vibration-free surface and avoid sudden temperature fluctuations [40]. |

Problem 3: Crystals with Poor Diffraction Quality

Symptoms: Crystals appear visually sound but diffract X-rays to low resolution or have high mosaicity.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Crystal Disorder | Perform post-crystallization dehydration treatments to gradually reduce solvent content and improve lattice order [41]. |

| Lattice Strain | Filter all solutions (including protein) through a 0.22 µm filter to remove particulates and impurities that become incorporated into the crystal [36]. |

| Intrinsic Flexibility | Chemically modify surface lysine residues via reductive methylation to reduce surface entropy and create new crystal contacts [43]. |

Table 1: Common Precipitants and Their Mechanisms

| Precipitant Class | Examples | Typical Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salts | Ammonium Sulfate, Sodium Chloride | 0.5 - 3.0 M | "Salting out" by competing with protein for water molecules, reducing hydration. | Robust, soluble proteins; often produces high-resolution crystals [40]. |

| Polymers | Polyethylene Gly (PEG) 400, 1K, 8K | 5 - 30% w/v | Excludes protein from solution volume, increasing effective concentration. | A wide variety of proteins; the most successful precipitant class [40]. |

| Organic Solvents | 2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), Ethanol | 2 - 30% v/v | Reduces water's dielectric constant, favoring protein-protein interactions. | Proteins stable in low-water conditions [42]. |

| Precipitant Mixtures | Salt/PEG, Salt/Organic Solvent | Varies | Synergistic effect; creates unique lattice interactions via multiple mechanisms [42]. | Salvaging difficult proteins that fail with single precipitants [42]. |

Table 2: Common Additives for Optimization

| Additive Category | Examples | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing Agents | DTT, TCEP | Stabilizes cysteine residues and prevents disulfide bond formation/breakage. | Essential for proteins with free cysteines; prevents oxidation. |

| Ions & Metals | MgCl₂, CaCl₂, ZnCl₂ | Can be essential cofactors; promote specific crystal contacts via coordination. | Use if protein is metallo-enzyme; screen various ions. |

| Solubilizing Agents | Glycerol, Sucrose | Stabilizes protein structure, prevents "oiling out," and increases solubility [10]. | Helpful for proteins that precipitate amorphously. |

| Surface Reducers | Chemical Modifiers (e.g., for reductive methylation) | Alters surface lysines to reduce conformational entropy, promoting crystal contacts [43]. | Salvage path for proteins failing to crystallize. |

| Detergents | β-Octyl Glucoside, DDM | Solubilizes membrane proteins; prevents aggregation of hydrophobic surfaces [41]. | Critical for membrane proteins; use at concentrations above CMC. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Hanging Drop Vapor Diffusion

This is the most widely used method for initial crystallization screening [40] [39].

- Prepare Reservoir: Fill the wells of a 24-well tray with 500 µL of precipitant solution.

- Prepare Protein: Clarify the protein solution by centrifugation (e.g., 15 min at 18,000 x g at 4°C) to remove aggregates. Keep on ice.

- Create Grease Seal: Apply a thin, continuous ring of silicone grease around the rim of each reservoir well.

- Mix Drop: On a clean, siliconized cover slide, pipette 1 µL of protein solution and 1 µL of reservoir solution. Mix gently by pipetting, avoiding bubbles.

- Seal Chamber: Invert the cover slide and carefully place it over the greased reservoir, ensuring a complete seal.

- Incubate and Observe: Gently place the tray at a constant temperature (e.g., 4°C or 20°C). Check the drops after 24 hours, and then regularly every few days.

Protocol 2: Reductive Methylation of Lysine Residues

This chemical modification can salvage proteins that fail to produce diffraction-quality crystals [43].

Principle: The ε-amino groups of surface lysine residues are dimethylated, reducing surface entropy and facilitating new crystal contacts.

Materials:

- Purified protein (5-20 mg at 5-10 mg/mL)

- 1M dimethylamine-borane complex (reducing agent)

- Formaldehyde (alkylating agent)

- Ice-cold buffer

Procedure:

- Cool Protein: Place the protein solution on ice.

- Add Reagents: To the stirred protein solution, add first the formaldehyde, then immediately the dimethylamine-borane complex. Typical final concentrations are 10-20 mM for each reagent.

- Incubate: Allow the reaction to proceed on ice for 2 hours.

- Quench and Purify: Dialyze or desalt the reaction mixture into your desired crystallization buffer to remove reaction byproducts.

- Screen: Subject the methylated protein to standard crystallization trials.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Troubleshooting Workflow

Reductive Methylation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Crystallization |

|---|---|

| Pre-Screen Kit | A small set of common precipitants to quickly test if a protein sample is at an appropriate concentration for crystallization trials [10]. |

| Sparse-Matrix Screen | Commercial screening kits (e.g., from Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions) that use an incomplete factorial design to efficiently sample a wide range of chemical conditions [40]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Instrument used to assess the monodispersity and hydrodynamic radius of a protein sample prior to crystallization. Aggregated samples are unlikely to crystallize [41]. |

| Centricon Concentrator | A centrifugal filtration device used to concentrate protein samples to the high concentrations (e.g., 10-50 mg/mL) typically required for crystallization [10]. |

| Siliconized Cover Slides | Glass cover slides treated to be hydrophobic, preventing the crystallization drop from spreading and ensuring it remains suspended in the hanging drop method [40]. |

| Paraffin Oil | Used in microbatch crystallization to seal nanoliter-volume drops from evaporation, allowing for high-throughput screening with minimal sample [40]. |

Diagnosing Problems and Refining Conditions for Better Crystals

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why can't I just optimize every hit from my initial screen? Protein and reagent resources are often limited. A decision matrix helps you invest these resources wisely by systematically ranking hits based on their potential to yield high-quality, diffraction-ready crystals, rather than pursuing optimization randomly or based on a single favorable characteristic [44] [45].

Q2: What is the most critical piece of information I need from my initial screening drops? A high-quality image of the drop is paramount. Advanced imaging techniques like Second Order Non-linear Imaging of Chiral Crystals (SONICC) can detect microcrystals, while Multifluorescence Imaging (MFI) can reliably distinguish protein crystals from salt crystals, providing the accurate data needed for scoring [46].