UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics in Metabolic Disease: Unraveling Lipid Pathways in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for uncovering lipidomic signatures in complex metabolic disorders.

UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics in Metabolic Disease: Unraveling Lipid Pathways in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Abstract

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for uncovering lipidomic signatures in complex metabolic disorders. This article explores the application of UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomics to investigate the intertwined pathophysiologies of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA). We detail the distinct lipid profiles—including upregulated triglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylcholines—that characterize these conditions and the central role of disrupted glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways. A structured framework is provided, covering foundational discoveries, methodological best practices for untargeted and targeted analysis, strategies for troubleshooting and data optimization, and approaches for biomarker validation. This resource is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage lipidomics for biomarker discovery and the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Lipidomic Landscapes: Discovering Dysregulated Pathways in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, provides a comprehensive approach to systematically analyze the entire lipid profile within a biological system. Lipids are not merely energy storage molecules but play crucial roles as structural components of cell membranes, signaling mediators, and regulators of metabolic processes. The structural diversity of lipids is immense, with estimates suggesting hundreds of thousands of molecular lipid species exist in biological systems [1]. In the context of metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and central obesity—lipidomics offers powerful insights into the underlying metabolic disturbances that conventional clinical chemistry cannot capture.

The application of advanced analytical technologies, particularly ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS), has revolutionized lipid research by enabling the identification and quantification of hundreds of lipid molecular species simultaneously. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomics within metabolic syndrome research, with specific emphasis on diabetes mellitus and hyperuricemia as interconnected metabolic disorders.

Analytical Foundations of UHPLC-MS/MS in Lipidomics

Core Technological Principles

UHPLC-MS/MS combines superior chromatographic separation with high-resolution mass spectrometry to address the complexity of the lipidome. Unlike "shotgun" lipidomics approaches that directly infuse samples into the mass spectrometer, UHPLC-MS/MS provides separation prior to mass analysis, which significantly reduces ion suppression effects and increases sensitivity [2]. The UHPLC system utilizes columns packed with sub-2-μm particles, enabling higher pressure operation and significantly improved chromatographic resolution compared to conventional HPLC.

Mass spectrometry detection typically employs high-resolution instruments such as quadrupole-time-of-flight (Q-TOF) or Orbitrap mass analyzers, which provide accurate mass measurements capable of determining elemental composition with sufficient precision to distinguish between lipid species with subtle mass differences [1]. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fragments selected precursor ions to provide structural information about fatty acyl chains, polar head groups, and other structural features.

Advantages Over Conventional Approaches

The UHPLC-MS/MS approach offers several critical advantages for lipidomic analysis:

- Enhanced Sensitivity: Detection limits in the femtomole range on-column enable quantification of low-abundance lipid signaling molecules [2]

- Structural Elucidation: MSⁿ capabilities allow detailed structural characterization, including identification of double bond positions and acyl chain composition [1]

- Isomer Separation: Chromatographic resolution can separate positional isomers of lysophospholipids and structural isomers of diacyl phospholipids and glycerolipids [2]

- Reduced Matrix Effects: Chromatographic separation minimizes ion suppression from co-eluting compounds, improving quantification accuracy [2]

Lipid Alterations in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetes Mellitus with Hyperuricemia

Recent lipidomic studies have revealed specific alterations in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and diabetes combined with hyperuricemia (DH). A 2025 study employing UHPLC-MS/MS analysis identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses in plasma samples from DH patients, DM patients, and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) controls [3]. Multivariate analyses revealed a significant separation trend among these groups, confirming distinct lipidomic profiles.

The study identified 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in the DH group compared to NGT controls [3]. The most prominent changes included:

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Classes in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia (DH) vs. Controls

| Lipid Class | Representative Molecules | Change in DH | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) | Significantly upregulated (13 TGs) | Associated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) | Significantly upregulated (10 PEs) | Membrane fluidity and signaling precursors |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) | Significantly upregulated (7 PCs) | Structural membrane components and signaling |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not specified | Downregulated | Altered signaling transduction |

Pathway analysis revealed that these differential lipid metabolites were predominantly enriched in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [3]. Furthermore, comparison of DH versus DM groups identified 12 differential lipids that were also predominantly enriched in these same core pathways, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes.

Comparative Lipidomics in Hyperuricemia

Independent lipidomic investigations focusing specifically on hyperuricemia (HUA) have identified additional metabolic disturbances. A UPLC-Q-TOF/MS-based study analyzing serum samples from HUA patients and healthy controls identified 138 differential metabolites in HUA serum, integrating analysis from seven different solvent extraction protocols [4]. These metabolites were involved in seven major metabolic pathways:

Table 2: Metabolic Pathways Altered in Hyperuricemia

| Metabolic Pathway | Key Lipid Classes Involved | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | Phosphatidylcholines, Phosphatidylethanolamines | Membrane integrity, signaling precursors |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | Ceramides, Sphingomyelins | Insulin resistance, apoptosis regulation |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes | Inflammation, immune response |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | Linoleic acid derivatives | Energy metabolism, membrane precursors |

| α-Linolenic acid metabolism | α-Linolenic acid derivatives | Anti-inflammatory effects, neuroprotection |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | Aromatic amino acid derivatives | Connection to purine metabolism |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis | Aromatic amino acids | Precursors to neurotransmitters and hormones |

The convergence of findings from both studies highlights the central importance of glycerophospholipid metabolism in both diabetes and hyperuricemia, suggesting shared metabolic disturbances that may explain their frequent co-occurrence.

Experimental Workflows in Lipidomics Research

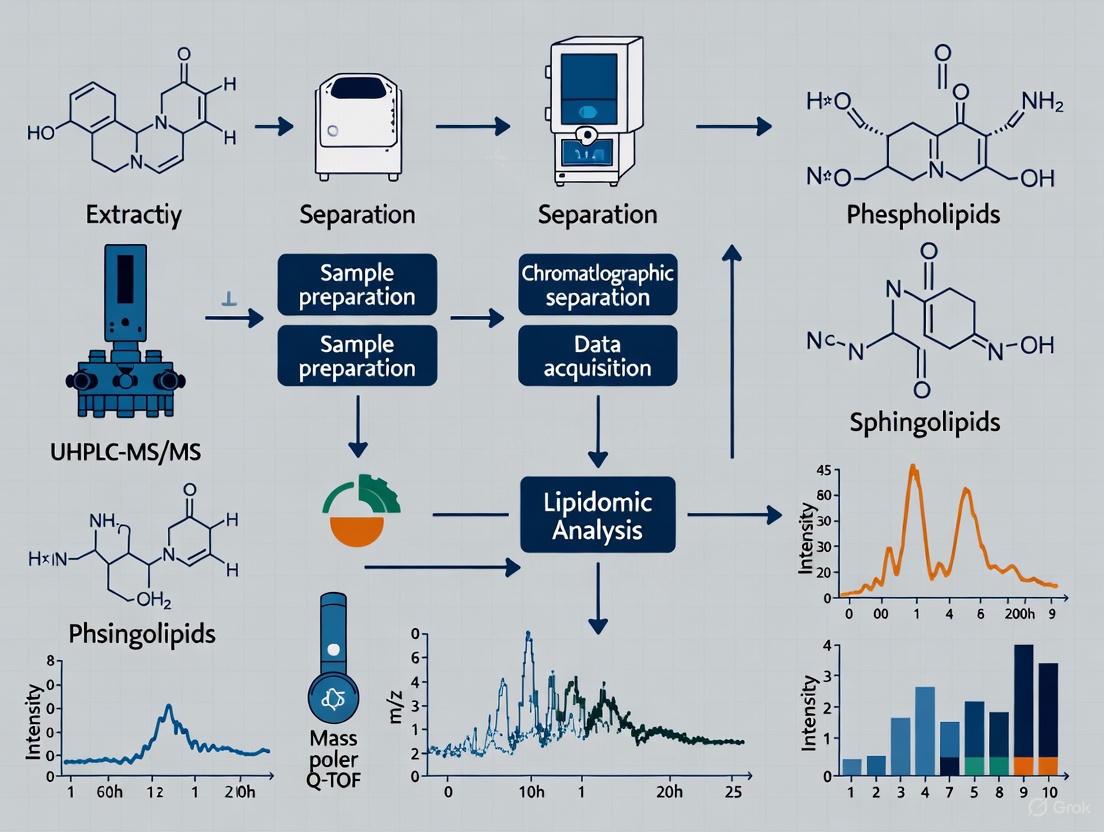

Standardized Lipidomics Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomic analysis from sample collection to data interpretation:

Sample Preparation and Extraction Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for comprehensive lipidomic analysis. For plasma or serum samples, the following liquid-liquid extraction method based on methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) is widely employed [3]:

- Sample Collection: Collect fasting blood samples and separate plasma/serum by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature [3]

- Lipid Extraction:

- Aliquot 100 μL of plasma into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube

- Add 200 μL of 4°C water and vortex mix

- Add 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol followed by 800 μL of MTBE

- Sonicate in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes

- Stand at room temperature for 30 minutes

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C

- Collect the upper organic phase and dry under nitrogen stream [3]

Alternative extraction methods include modified Folch extraction (chloroform:methanol, 2:1) for broader lipid class coverage [1]. The choice of extraction solvent significantly impacts lipid coverage, with different methanol-acetonitrile ratios yielding varying numbers of detected lipid species [4].

UHPLC-MS/MS Analytical Conditions

Standardized chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions are essential for reproducible lipidomic analysis:

Chromatographic Conditions [3] [1]:

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in water or 0.2% formic acid aqueous solution

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-isopropanol or methanol with modifiers

- Gradient: Typically from 35-100% organic phase over 7-15 minutes

- Temperature: 45-50°C

- Flow Rate: 0.400 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 2.0 μL

Mass Spectrometry Conditions [3] [4]:

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive and negative modes

- Mass Range: m/z 300-1200 or 50-1200

- Ion Spray Voltage: 3.0 kV

- Source Temperature: 120-450°C

- Resolution: High-resolution setting (R = 60,000 for Orbitrap instruments)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Primary extraction solvent for liquid-liquid extraction | Chromasolv grade or equivalent [3] [2] |

| Methanol, Acetonitrile, Isopropanol | Organic solvents for extraction and mobile phases | LC-MS grade, Chromasolv grade [3] [2] |

| Ammonium formate | Mobile phase additive for improved ionization | LC-MS grade [3] [2] |

| Formic acid | Mobile phase modifier for protonation in positive mode | LC-MS grade [4] |

| Internal Standards | Quantification standardization | Deuterated or 13C-labeled lipid standards [2] |

| C18 UHPLC Column | Chromatographic separation | 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size [3] [1] |

Metabolic Pathways in Lipidomics

The following diagram illustrates the key metabolic pathways identified as significantly altered in diabetes with hyperuricemia, based on lipidomic studies:

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Lipidomic data processing involves multiple steps to convert raw mass spectrometric data into biologically meaningful information:

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Software tools (e.g., Progenesis QI, MZmine 2) detect chromatographic peaks and align them across samples [4] [1]

- Normalization: Data normalization using internal standards and quality control samples corrects for technical variability [4]

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis:

- Differential Analysis: Statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test) combined with fold-change calculations identify significantly altered lipids [3]

- Pathway Analysis: Platforms such as MetaboAnalyst 5.0 identify enriched metabolic pathways based on the differential lipid species [3]

Lipidomics has emerged as an essential tool for unraveling the complex metabolic disturbances in metabolic syndrome, particularly in the interplay between diabetes and hyperuricemia. The identification of specific lipid signatures and perturbed pathways provides insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

Future directions in the field include:

- Standardization of analytical protocols and nomenclature through initiatives such as the Lipidomics Standards Initiative [5]

- Integration of lipidomics with other omics technologies for comprehensive systems biology understanding

- Development of improved computational tools for lipid identification and pathway analysis

- Application of stable isotope labeling for dynamic monitoring of lipid fluxes in metabolic pathways [5]

The continued advancement of UHPLC-MS/MS platforms and analytical methodologies will further enhance our understanding of lipid metabolism in metabolic syndrome, potentially leading to novel diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic interventions for diabetes, hyperuricemia, and their associated complications.

The comorbidity of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and Hyperuricemia (HU) presents a significant clinical challenge, with growing evidence suggesting that their confluence exacerbates disruptions in lipid metabolism. Conventional clinical biomarkers often fail to capture the full spectrum of these metabolic alterations. Within the context of a broader thesis on UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic analysis in metabolic disease research, this technical guide delineates the distinct plasma lipidomic signatures that differentiate patients with diabetes alone from those with diabetes combined with hyperuricemia (DH). The application of advanced lipidomics provides a powerful tool for researchers and drug development professionals to uncover novel biomarkers and elucidate perturbed metabolic pathways, thereby informing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Lipidomic Landscape: DM vs. DH

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) based lipidomic studies have successfully characterized the specific lipid disturbances associated with DM and DH. A comparative analysis reveals both shared and unique lipidomic footprints.

Table 1: Key Lipid Class Alterations in DM vs. DH

| Lipid Class | Trend in DM | Trend in DH (vs. DM or Healthy) | Specific Lipid Examples (with notation) | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | Commonly elevated [6] | Significantly Upregulated [3] | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2), TG(17:0/17:0/17:0) [3] [7] | Primary energy storage; markers of energy metabolic flux. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | Altered levels [6] [8] | Significantly Upregulated [3] | PC(36:1), PC(18:0/20:3) [3] [7] | Major membrane phospholipids; involved in signaling. |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | Altered levels [6] [7] | Significantly Upregulated [3] | PE(18:0/20:4) [3] | Membrane phospholipids; promote membrane curvature. |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) | Downregulated in T2DM [8] [9] | Information Not Specified | LPC(18:0), LPC(18:1), LPC(18:2) [8] | Pro-inflammatory mediators; correlated with HOMA-IR. |

| Ceramides (Cer) | Upregulated in T2DM [6] [9] | Information Not Specified | Cer(d18:1/24:0), 1-deoxyceramides [6] [9] | Pro-apoptotic signaling molecules; implicated in insulin resistance. |

| Sphingomyelins (SM) | Associated with T2DM risk [6] | Information Not Specified | SM(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/16:1) [6] | Membrane sphingolipids; precursors to ceramides. |

A study directly comparing DH, DM, and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) groups identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses. Multivariate analyses confirmed a significant separation trend among these groups. Specifically, 31 lipid metabolites were significantly altered in the DH group compared to NGT controls. Among the most relevant, 13 triglycerides (TGs), 10 phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and 7 phosphatidylcholines (PCs) were significantly upregulated, while one phosphatidylinositol (PI) was downregulated [3]. This pattern suggests a massive disruption in glycerolipid and glycerophospholipid metabolism in the comorbid condition.

In contrast, lipidomic studies of T2DM populations have highlighted alterations in different lipid species. For instance, significant changes in lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), sphingomyelin (SM), and ceramide (Cer) have been reported [6]. A large-scale study of 293 Chinese individuals found that lipid features gradually changed from NGT to prediabetes to T2DM, and identified specific LysoPCs (e.g., LPC(18:0), LPC(18:1), LPC(18:2)) that were negatively correlated with the insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) [8]. Furthermore, a comparative study between T1D and T2D found that LPCs and Ceramides showed opposite effects; LPCs were mainly upregulated in T1D and down-regulated in T2D, while Ceramides were upregulated in T2D and down-regulated in T1D [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

The reliability of lipidomic data is contingent upon rigorous and standardized experimental protocols. The following methodology is synthesized from key studies investigating lipid metabolism in diabetes and hyperuricemia [3] [7].

Sample Collection and Pre-processing

- Sample Type: Fasting venous blood samples are collected.

- Processing: Blood samples are centrifuged (e.g., 3,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature) to isolate plasma or serum. The upper layer of plasma is aliquoted and stored at -80 °C until analysis.

- Quality Control (QC): Aliquots from all samples are combined to create a pooled QC sample, which is injected at regular intervals throughout the analytical run to monitor instrument stability and data reproducibility [3] [9].

Lipid Extraction

The modified Folch or MTBE method is widely employed for comprehensive lipid recovery:

- Aliquot: 100 μL of plasma.

- Precipitate Proteins: Add 200 μL of 4°C water and 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol. Vortex to mix.

- Extract Lipids: Add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). Vortex and sonicate in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes.

- Phase Separation: Allow the mixture to stand at room temperature for 30 minutes. Centrifuge at 14,000 g at 10°C for 15 minutes.

- Recover Organic Phase: The upper organic phase, which contains the lipids, is collected and dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- Reconstitution: The dried lipid extract is reconstituted in 100 μL of isopropanol or a suitable mobile phase for MS analysis [3] [10].

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis Conditions

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) or similar.

- Mobile Phase:

- A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water (e.g., 60:40 v/v).

- B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol (e.g., 10:90 v/v).

- Gradient: A typical gradient runs from 30% B to 100% B over 25 minutes, followed by re-equilibration.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 - 0.4 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 40 - 45°C.

- Injection Volume: 2 - 3 μL [3] [9].

Mass Spectrometry Conditions:

- Ionization: Heated Electrospray Ionization (H-ESI) in both positive and negative ion modes.

- Spray Voltage: +5.5 kV (positive), -4.5 kV (negative).

- Ion Source Temperature: 300 - 350°C.

- Sheath Gas & Auxiliary Gas: Optimized for nebulization and desolvation (e.g., 45 and 15 arbitrary units).

- Scan Mode: Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) or Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) for untargeted analysis; Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for targeted analysis [3] [11].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

- Peak Alignment & Identification: Software such as Progenesis QI, MS-DIAL, or commercial and in-house pipelines are used for peak picking, alignment, and lipid identification against reference databases (e.g., LIPID MAPS).

- Multivariate Statistics: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) are applied to observe group separations and identify differentially abundant lipids.

- Differential Analysis: Student's t-test and fold-change analysis are used for initial screening.

- Pathway Analysis: Platforms like MetaboAnalyst 5.0 are used to map differentially expressed lipids onto metabolic pathways based on enrichment analysis and pathway impact values [3] [8].

Metabolic Pathway Disturbances

The distinct lipid profiles in DM and DH are underpinned by specific perturbations in key metabolic pathways. Pathway enrichment analysis of the 31 significantly altered lipids in DH patients revealed their enrichment in six major pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value 0.014) identified as the most significantly disturbed [3]. The central role of these pathways is further underscored by the finding that differential lipids between DH and DM groups were also predominantly enriched in these same core pathways [3].

In studies focused on T2DM with dyslipidemia, sphingolipid metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism have been identified as the most relevant pathways associated with glucose and lipid metabolism changes [6]. Furthermore, research in hyperuricemia patients has also identified significant involvement of glycerophospholipid metabolism, along with arachidonic acid, linoleic acid, and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism pathways [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Item Category | Specific Examples & Specifications | Critical Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (1.7 µm, 2.1x100mm); Kinetex C18 [3] [11] | High-resolution separation of complex lipid extracts prior to MS detection. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Q Exactive Focus (Orbitrap); TripleTOF; QTrap 6500+ [7] [9] | Accurate mass measurement and structural characterization via tandem MS. |

| Lipid Internal Standards | PC(14:0)-d13, TG(17:0/17:0/17:0), Cer(d18:1/17:0) [7] | Absolute quantification and correction for extraction/ionization variability. |

| Solvents (HPLC/MS Grade) | Acetonitrile, Isopropanol, Methanol, Chloroform, MTBE [3] [7] | Lipid extraction, mobile phase preparation, and column cleaning. |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Ammonium Formate, Ammonium Acetate, Formic Acid [3] [9] | Enhance ionization efficiency and control chromatographic peak shape. |

| Sample Vials & Plates | Low Recovery/Volume Vials (e.g., 0.3 mL) [9] | Minimize sample loss and ensure compatibility with autosampler systems. |

Visualizing the Lipidomics Workflow

The entire process, from sample collection to biological insight, can be summarized in the following workflow, which integrates the key tools and steps detailed in the previous sections.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The distinct lipid profiles delineated through UHPLC-MS/MS analysis highlight that Diabetes Mellitus with Hyperuricemia (DH) is not merely an additive condition but one with a unique and exacerbated lipidomic signature, characterized primarily by a pronounced upregulation of triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), driven by core disturbances in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism [3]. This contrasts with lipidomic patterns in T2DM alone, which often feature more prominent alterations in sphingolipids like ceramides and a downregulation of specific lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) [6] [8] [9].

The translational potential of these findings is significant. The identified differential lipid species, such as the specific TGs and PCs, serve as candidate biomarkers for stratifying patient risk and diagnosing the comorbid condition. Furthermore, the elucidated pathways present novel targets for therapeutic intervention. However, challenges remain in the clinical application of lipidomic biomarkers, including the need for standardized protocols, multi-center validation studies, and sophisticated bioinformatics tools to handle the complex data [12]. Future research directions should focus on longitudinal studies to establish causality, the integration of lipidomics with other omics data, and the development of machine learning models to improve the predictive power of lipid-based diagnostic panels [12]. This precise mapping of the lipidomic landscape in DM and DH paves the way for more personalized and effective management strategies for these complex metabolic disorders.

Lipidomic profiling using advanced analytical techniques like ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has revolutionized our understanding of metabolic diseases. This approach provides a comprehensive picture of lipid metabolic disorders throughout the body, offering new avenues for identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets [3]. In the context of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia—conditions often characterized by significant lipid abnormalities—lipidomics serves as an effective tool to characterize specific lipid perturbations that precede and accompany disease progression [3] [13].

The dysregulation of three key lipid classes—triglycerides (TGs), glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids—has emerged as particularly significant in diabetes and hyperuricemia research. These lipids not only serve as structural components and energy stores but also function as bioactive molecules in signaling pathways that influence insulin resistance, inflammation, and cellular dysfunction [13] [14]. Understanding the precise alterations in these lipid species provides crucial insights into disease mechanisms and potential intervention points.

This technical guide synthesizes current evidence on TG, glycerophospholipid, and sphingolipid dysregulation in diabetes and hyperuricemia, with a specific focus on UHPLC-MS/MS methodologies for lipidomic analysis. We present quantitative data from recent studies, detailed experimental protocols, relevant metabolic pathways, and essential research tools to support further investigation in this rapidly advancing field.

Lipid Dysregulation in Metabolic Disease

Triglycerides (TGs)

Triglycerides, consisting of three fatty acids esterified to a glycerol backbone, represent the most abundant energy reserve in the body. Recent lipidomic studies have revealed that specific TG subspecies are significantly altered in metabolic diseases, providing more precise information than traditional clinical measurements of total triglycerides [3] [6].

In patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), 13 different TG molecules were significantly upregulated compared to healthy controls [3]. A key finding was the marked upregulation of TG (16:0/18:1/18:2) in DH patients, suggesting particular disruption in fatty acid handling and storage. These TG alterations were enriched in the glycerolipid metabolism pathway (impact value: 0.014), indicating its central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [3].

Table 1: Significant Triglyceride Alterations in Metabolic Diseases

| TG Subspecies | Change in DH vs. Control | Change in T2DM vs. Control | Associated Metabolic Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG (16:0/18:1/18:2) | Significantly upregulated [3] | Not specified | Glycerolipid metabolism [3] |

| Multiple other TGs | 12 additional TGs upregulated [3] | Not specified | Glycerolipid metabolism [3] |

| Total TG profile | Not specified | Elevated in T2DM with dyslipidemia [6] | Energy metabolism, Lipid storage |

Glycerophospholipids

Glycerophospholipids, including phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and phosphatidylinositols (PIs), are essential structural components of cellular membranes and play crucial roles in cell signaling [3] [14]. Lipidomic analyses have identified distinct alterations in specific glycerophospholipid species across different metabolic conditions.

In DH patients, 10 phosphatidylethanolamines, including PE (18:0/20:4), and 7 phosphatidylcholines, including PC (36:1), were significantly upregulated, while one phosphatidylinositol was downregulated [3]. These alterations were predominantly enriched in the glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway (impact value: 0.199), which was identified as the most significantly perturbed pathway in DH patients [3].

Table 2: Glycerophospholipid Alterations in Metabolic Diseases

| Glycerophospholipid Class | Specific Molecules | Change in Disease vs. Control | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE (18:0/20:4) | Upregulated in DH [3] | Membrane fluidity, signaling |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC (36:1) | Upregulated in DH [3] | Membrane structure, lipid signaling |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC) | Multiple species | Altered in T2DM with dyslipidemia [6] | Pro-inflammatory signaling |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | One unspecified PI | Downregulated in DH [3] | Cell signaling, membrane trafficking |

Sphingolipids

Sphingolipids, characterized by a sphingoid base backbone, include diverse subclasses such as ceramides (Cer), sphingomyelins (SM), and sphingosine-1-phosphate (So1P). These lipids function not only as structural membrane components but also as potent signaling molecules that influence insulin sensitivity, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses [14] [15].

Research has demonstrated that sphingolipid metabolism is profoundly dysregulated in type 2 diabetes. In a study of 245 participants, sphingosine-1-phosphate (So1P) levels were highest in healthy controls and gradually decreased as the disease progressed to pre-diabetes and overt T2DM [15]. Other sphingolipids, including glucosylceramide (GluCer), sphingomyelin (SM), sphinganine (Sa), and sphingosine (So), exhibited a 'U'-shaped change during diabetes progression, decreasing in pre-diabetes and rising again in established T2DM [15]. Notably, So1P and Sa were identified as significant predictors of cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients [15].

In newly diagnosed T2DM patients with dyslipidemia, specific sphingolipids including Cer(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/16:1), SM(d18:1/24:1), and SM(d18:2/24:1) were identified as essential potential biomarkers strongly correlated with clinical parameters [6]. These molecules were associated with the sphingolipid metabolism pathway, which was recognized as highly relevant to glucose and lipid metabolism changes in T2DM [6].

Figure 1: Sphingolipid Metabolism Pathway. Key enzymes: SPT (serine palmitoyltransferase), CerS (ceramide synthase), GCS (glucosylceramide synthase), SphK (sphingosine kinase). Ceramide and sphingomyelin accumulation (red) is associated with insulin resistance, while decreased S1P (yellow) correlates with diabetes progression and cardiovascular complications [15].

UHPLC-MS/MS Methodologies for Lipidomic Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for reliable lipidomic analysis. Based on recent studies, the following protocols have been employed for plasma/serum sample processing:

Plasma Sample Preparation (from [3]):

- Collect 5 mL of fasting blood and centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Aliquot 0.2 mL of upper plasma layer into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes

- Store at -80°C until analysis

- Thaw samples on ice and vortex

- Aliquot 100 μL into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube

- Add 200 μL of 4°C water and mix

- Add 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol and mix

- Add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and mix

- Sonicate for 20 minutes in a low-temperature water bath

- Let stand at room temperature for 30 minutes

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C

- Collect upper organic phase and dry under nitrogen

Serum Sample Preparation (from [16]):

- Collect blood after overnight fast and centrifuge at 3,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes

- Aliquot 50 μL of serum

- Mix with 50 μL methanol and 250 μL methyl tert-butyl ether

- Vortex for 1 minute

- Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes

- Collect 200 μL supernatant and dry using vacuum freeze-drying equipment

- Reconstitute in 100 μL of isopropyl alcohol-acetonitrile-water (2:1:1) solution

- Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes and collect supernatant for UHPLC-MS analysis

UHPLC-MS/MS Analytical Conditions

Chromatographic Conditions (from [3] and [16]):

- System: Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm length, 1.7 μm particle size) [3] or ACQUITY BEH C8 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) [16]

- Column Temperature: 40°C [16]

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile solution in water [3] or methanol-acetonitrile-water (1:1:1) solution containing 5 mmol/L ammonium acetate [16]

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile isopropanol solution [3] or isopropanol solution containing 5 mmol/L ammonium acetate [16]

- Gradient Program (from [16]):

- Start at 80% A

- Linearly decrease to 60% A over 2.5 minutes

- Hold at 60% A for 1.5 minutes

- Linearly decrease to 10% A over 14 minutes

- Hold for 1 minute

- Increase to 80% A for 0.1 minute and hold for 1.9 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.30 mL/min [16]

- Injection Volume: 4 μL for all samples [16]

Mass Spectrometric Conditions (from [16]):

- System: AB SCIEX Triple TOF 5500 mass analyzer with information-dependent acquisition (IDA)

- Ion Spray Voltage: +5500 V (positive mode) and -4500 V (negative mode)

- Gas 1: 50 psi

- Gas 2: 55 psi

- Curtain Gas: 25 psi

- Drying Temperature: 500°C

- Collision-activated dissociation (CAD): Set as medium

Figure 2: UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics Workflow. The process encompasses sample collection through pathway analysis, with critical separation and detection steps (yellow) and complex data analysis phases (red) [3] [16].

Metabolic Pathways and Biological Significance

The dysregulated lipid classes discussed interact in complex metabolic networks that contribute to the pathophysiology of diabetes and hyperuricemia. Lipidomic studies have identified several key pathways that are significantly perturbed in these conditions.

In diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) were identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways [3]. These findings were consistent across comparisons between DH, DM, and healthy control groups, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes.

In proliferative diabetic retinopathy, a major complication of diabetes, sphingolipid metabolism was significantly enriched among the altered metabolic pathways, along with sulfur metabolism and cysteine and methionine metabolism [17]. This highlights the involvement of sphingolipids in diabetic microvascular complications.

For newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes with dyslipidemia, sphingolipid metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism were identified as the most relevant pathways to glucose and lipid metabolism changes [6]. The interconnected nature of these pathways creates a complex metabolic network that drives disease progression and complication development.

Table 3: Key Dysregulated Metabolic Pathways in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Metabolic Pathway | Impact Value/ Significance | Associated Lipid Classes | Biological Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | Impact value: 0.199 in DH [3] | Phosphatidylcholines, Phosphatidylethanolamines, Phosphatidylinositols | Membrane dysfunction, altered cell signaling |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | Impact value: 0.014 in DH [3] | Triglycerides, Diglycerides | Energy metabolism dysregulation, lipid storage |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | Significantly enriched in PDR [17] | Ceramides, Sphingomyelins, Sphingosine-1-phosphate | Insulin resistance, apoptosis, inflammation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Lipidomic Studies in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) [3], ACQUITY BEH C8 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) [16] | Lipid separation based on hydrophobicity |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Ammonium formate [3], Ammonium acetate [16] | Enhance ionization efficiency in MS |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [3] [16], Methanol, Isopropyl alcohol [16] | Lipid extraction from biological samples |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Not specified in results, but internal standards for each lipid class are recommended | Quantification and quality control |

| Data Analysis Software | MetaboAnalyst 5.0 [3] [16], GraphPad Prism [16] | Statistical analysis, pathway mapping, visualization |

UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomic analysis has revealed systematic dysregulation of triglycerides, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids in diabetes and hyperuricemia. The distinct patterns of alteration in specific lipid subspecies within these classes provide greater insights into disease mechanisms than traditional lipid measurements. The consistency of findings across multiple studies—particularly the perturbations in glycerophospholipid, glycerolipid, and sphingolipid metabolism pathways—highlights their fundamental role in disease pathophysiology.

The translational potential of these findings is significant, with specific lipid species emerging as promising biomarkers for early detection, risk stratification, and monitoring of diabetes, hyperuricemia, and their complications. However, challenges remain in standardizing methodologies, validating findings across diverse populations, and translating lipidomic signatures into clinical practice. Future research should focus on addressing these challenges while further elucidating the complex relationships between lipid dysregulation and metabolic disease progression.

Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, provides a comprehensive analysis of lipid molecules within biological systems, enabling the characterization of specific lipid disruptions in metabolic diseases [12]. In the context of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA)—two prevalent and often co-occurring metabolic disorders—lipidomic profiling using advanced technologies like UHPLC-MS/MS has revealed significant alterations in core metabolic pathways, particularly glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism [3]. These pathways are crucial for maintaining cellular membrane integrity, energy storage, and signaling processes. Their dysregulation offers critical insights into the pathophysiology of these conditions and presents opportunities for biomarker discovery. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these pathways, framed within contemporary lipidomics research on diabetes and hyperuricemia, and details the experimental methodologies used to investigate them.

Pathway Biochemistry and Physiological Context

Glycerophospholipid Metabolism

Glycerophospholipids are glycerol-based phospholipids that serve as the main structural component of biological membranes in eukaryotic cells [18]. Their amphipathic nature—featuring a hydrophilic polar head group and two hydrophobic fatty acyl chains—drives the formation of the lipid bilayer [18]. The metabolism of glycerophospholipids begins with the acylation of glycerol-3-phosphate to form lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which is subsequently acylated to phosphatidic acid (PA) [18]. PA is a key intermediate that can be dephosphorylated to diacylglycerol (DAG), a precursor for the synthesis of major species such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) via the Kennedy pathway [18]. Beyond their structural role, glycerophospholipids are reservoirs for second messengers, including DAG, phosphatidic acid, and arachidonic acid derivatives, which are involved in signal transduction, apoptosis, and modulation of transporter and enzyme activities [18].

Glycerolipid Metabolism

The glycerolipid metabolism pathway primarily centers on the biosynthesis and degradation of triacylglycerols (TGs) and their precursors [19]. The core biosynthesis module (M00089) involves the sequential acylation of the glycerol backbone to form TGs, which serve as the body's principal energy storage molecules in adipose tissue [19]. The degradation module (M00098) encompasses the breakdown of acylglycerols, releasing fatty acids and glycerol for energy production or further metabolic processing. Dysregulation of this pathway, particularly the excessive accumulation of TGs, is a hallmark of dyslipidemia, which frequently accompanies insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [20].

Lipidomic Alterations in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) based lipidomics has identified distinct perturbations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolites in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperuricemia (HUA), and their co-occurrence (DH).

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Metabolites in Metabolic Disorders

| Lipid Class | Specific Metabolites | Trend in DH vs NGT | Trend in DH vs DM | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significantly Upregulated [3] | Not Specified | Energy storage; Elevated levels indicate dyslipidemia [3] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significantly Upregulated [3] | Not Specified | Membrane structure; Source of signaling precursors [3] |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significantly Upregulated [3] | Not Specified | Major membrane phospholipid; precursor for signaling molecules [3] |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not Specified | Downregulated [3] | Not Specified | Signaling lipid; involved in insulin signaling pathways [3] |

| Sphingomyelins (SMs) | SM(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/16:1) | Not Reported in DH | Not Reported in DH | Membrane integrity; Ceramide precursors; associated with T2DM dyslipidemia [20] |

| Ceramides (Cer) | Cer(d18:1/24:0) | Not Reported in DH | Not Reported in DH | Signaling lipids implicated in insulin resistance [20] |

A study on patients with diabetes and hyperuricemia (DH) identified 1,361 lipid molecules and found 31 to be significantly altered compared to healthy controls (NGT). The dyslipidemia was characterized by a pronounced upregulation of 13 TGs, 10 PEs, and 7 PCs, alongside a downregulation of one PI [3]. Multivariate analyses confirmed a distinct lipidomic profile separating the DH, DM, and NGT groups [3]. Furthermore, the comparison between DH and DM groups identified 12 differential lipids, underscoring a unique lipid signature for the comorbid condition [3].

Independent research on type 2 diabetes with dyslipidemia (NDDD) has reinforced the centrality of these pathways, identifying significant changes in lipid species including lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC), PC, PE, sphingomyelin (SM), and ceramide (Cer) [20]. The study highlighted sphingolipid metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism as the most relevant pathways disturbed in the context of both glucose and lipid metabolism dysregulation [20].

Table 2: Enriched Metabolic Pathways and Associated Biomarkers

| Metabolic Pathway | Impact Value / Relevance | Key Associated Biomarkers | Related Clinical Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid Metabolism | Impact: 0.199 (Most significant in DH) [3] | PC, PE, LysoPC [3] [20] | DH [3], T2DM with Dyslipidemia [20], HUA [10] |

| Glycerolipid Metabolism | Impact: 0.014 (Significant in DH) [3] | TG, DAG [3] | DH [3] |

| Sphingolipid Metabolism | Considered most relevant [20] | Cer(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/24:0) [20] | T2DM with Dyslipidemia [20] |

| Arachidonic Acid Metabolism | Involved [10] | Metabolites of Arachidonic Acid [10] | HUA [10] |

| GPI-Anchor Biosynthesis | Involved [10] | Not Specified | HUA [10] |

Pathway enrichment analysis using the MetaboAnalyst 5.0 platform on data from the DH study revealed that the differential lipids were predominantly enriched in glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value of 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value of 0.014), confirming these as the most significantly perturbed pathways in the comorbid condition [3]. This finding is consistent with other studies showing that glycerophospholipid metabolism is also a key disrupted pathway in hyperuricemia alone, where it is linked to altered levels of immune factors such as IL-6, TGF-β1, and CPT1 [10].

Experimental Workflow for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

The following diagram and subsequent sections detail the standard experimental protocol for an untargeted lipidomic analysis of plasma samples, as utilized in the cited research.

Diagram 1: Lipidomics Experimental Workflow

Sample Collection and Preparation

- Study Population: Participants are typically recruited based on well-defined diagnostic criteria (e.g., ADA guidelines for diabetes, uric acid levels >420 μmol/L in men for HUA). Age and sex matching with healthy controls is critical. Exclusion criteria often include the use of hypoglycemic, lipid-lowering, or urate-lowering drugs, as well as the presence of other conditions like gout, renal disease, or cancer [3] [20].

- Plasma Collection: Fasting blood samples (e.g., 5 mL) are collected into appropriate anticoagulant tubes. The samples are centrifuged (e.g., 3,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature) to separate plasma, which is then aliquoted and stored at -80°C until analysis [3] [10].

- Lipid Extraction: The methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) method is widely used. A typical protocol involves:

- Thawing plasma samples on ice.

- Vortexing and aliquoting 100 μL of plasma into a tube.

- Adding 200 μL of ice-cold water and 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol.

- Adding 800 μL of MTBE, followed by sonication in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes and standing at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuging at 14,000 g at 10°C for 15 minutes to achieve phase separation.

- Collecting the upper organic phase and drying it under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

- Reconstituting the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent (e.g., 90% isopropanol/acetonitrile) for LC-MS injection [3] [10].

- Quality Control (QC): Pooled QC samples are prepared by combining equal volumes of all study samples. These QC samples are injected at regular intervals throughout the analytical run to monitor instrument stability and data quality [3] [20].

UHPLC-MS/MS Analytical Conditions

The following table summarizes the core components of the UHPLC-MS/MS setup as described in the research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials

| Item | Typical Specification / Brand | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 μm) [3] | Separation of complex lipid mixtures |

| Mobile Phase A | 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water (e.g., 60:40, v/v) [3] [20] | Aqueous-organic phase for gradient elution |

| Mobile Phase B | 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol (e.g., 10:90, v/v) [3] [20] | Strong organic phase for gradient elution |

| Mass Spectrometer | Q-Exactive Plus (Thermo Scientific) [20] | High-resolution mass detection and fragmentation |

| Ionization Source | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Soft ionization of lipid molecules |

| Lipid Extraction Solvent | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [3] [10] | Liquid-liquid extraction of lipids from plasma |

| Data Analysis Software | MS DIAL, Lipostar, XCMS [12] | Peak picking, alignment, and lipid identification |

- Chromatographic Conditions: Lipid separation is achieved using a reverse-phase UHPLC system. A typical gradient for a C18 column involves starting at 30% mobile phase B, ramping to 100% B over 20-25 minutes, holding, and then re-equilibrating to the initial conditions. The flow rate is maintained around 300 μL/min, and the column temperature is kept at 45-55°C [3] [20] [10].

- Mass Spectrometric Conditions: Data are acquired in both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize lipid coverage. Key parameters for a Q-Exactive Plus instrument include:

- Sheath Gas Flow: 45 arb

- Aux Gas Flow: 15 arb

- Spray Voltage: 3.0 kV (positive), 2.5 kV (negative)

- Capillary Temperature: 350°C

- Scan Range: 200-1800 m/z

- Resolution: 70,000 for MS1, 17,500 for MS/MS [20] [10]. Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) is commonly employed, where the top N most intense ions from the MS1 scan are selected for fragmentation to generate MS/MS spectra for lipid identification.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

- Lipid Identification and Quantification: Raw data are processed using software platforms (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar) for peak picking, alignment, and deconvolution. Lipids are identified by matching the accurate mass of the precursor ion (MS1) and its fragmentation spectrum (MS/MS) against theoretical spectra in lipid databases [12].

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Processed data are subjected to:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): An unsupervised method to visualize overall clustering and outliers among sample groups.

- Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA): A supervised method to maximize separation between predefined groups and identify lipids that contribute most to the separation [3] [20].

- Differential Analysis and Pathway Mapping: Lipids with a combination of a statistically significant p-value (e.g., < 0.05 from Student's t-test), a large fold-change (FC > 2 or < 0.5), and a high variable importance in projection (VIP) score from OPLS-DA (>1.0) are considered differential lipids [3] [20]. These lipids are then input into pathway analysis tools like MetaboAnalyst 5.0 to identify enriched metabolic pathways based on database references such as KEGG [3].

Integrated Pathway Diagram

The diagram below synthesizes the core interactions between the glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways and highlights the key lipid species found to be altered in diabetes and hyperuricemia research.

Diagram 2: Core Glycerolipid/Glycerophospholipid Pathways

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The consistent identification of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism as central pathways in diabetes, hyperuricemia, and their comorbidity underscores a profound lipidic component to these diseases. The upregulation of TGs aligns with clinical observations of dyslipidemia, while the distinct shifts in specific PC, PE, and PI species suggest more nuanced disruptions in membrane dynamics and cell signaling that may contribute to insulin resistance, inflammation, and cellular dysfunction [3] [20] [18]. The lipidomic signatures uncovered through UHPLC-MS/MS hold significant promise as panels of biomarkers for early detection, risk stratification, and monitoring of disease progression and therapeutic intervention [20] [12].

Future research directions should focus on the multi-omics integration of lipidomic data with genomics and proteomics to build a more comprehensive network of pathogenic mechanisms [12]. Furthermore, large-scale, multi-center validation studies are essential to standardize methodologies and translate these lipid biomarkers from research tools into clinically applicable diagnostics [12]. As lipidomics technologies continue to advance and bioinformatic tools become more sophisticated, the depth of our understanding of these critical metabolic pathways will undoubtedly expand, opening new avenues for targeted therapies and personalized medicine in metabolic disease.

Connecting Lipid Dysregulation to Pathophysiology and Comorbidities

Lipid dysregulation represents a core pathological event in a spectrum of metabolic diseases, contributing significantly to organ damage and the progression of comorbidities. The intricate relationship between disordered lipid metabolism and disease is particularly evident in the common coexistence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA), where lipid abnormalities exacerbate the risk of cardiovascular, renal, and other diabetic complications. Advanced lipidomic technologies, specifically ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS), are uncovering the specific lipid species and pathways involved. This whitepaper details how lipid dysregulation drives pathophysiology in conditions like diabetes and hyperuricemia, summarizes key experimental findings in a structured format, and provides detailed methodologies for lipidomic analysis, serving as a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Comorbidities

The Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Metabolic Crosstalk

The coexistence of diabetes and hyperuricemia is synergistic, creating a vicious cycle of metabolic dysregulation. This comorbidity exacerbates damage to vital organs, particularly the cardiovascular system and kidneys [21]. Key mechanisms include:

- Insulin Resistance: Hyperuricemia contributes to insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell apoptosis, which in turn worsens glycemic control [21].

- Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: Elevated uric acid levels promote oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways, aggravating diabetic complications such as cardiomyopathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy [21].

- Lipid Dysregulation as a Common Link: Both disorders are independently and collectively associated with profound abnormalities in lipid metabolism, which underpin much of the shared pathophysiology [3] [22].

Core Lipid Pathways in Disease

Lipidomics studies have identified several key metabolic pathways that are consistently perturbed in metabolic diseases:

- Glycerophospholipid Metabolism: This pathway is significantly altered in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia (DH), with an impact value of 0.199, making it one of the most significantly disturbed pathways [3].

- Glycerolipid Metabolism: Also highly relevant in DH patients, this pathway shows an impact value of 0.014 [3].

- Sphingolipid Metabolism: Ceramides, a class of sphingolipids, are significantly elevated in various pathological states and are associated with insulin resistance, inflammation, and apoptosis. In depression, which exhibits comorbidity with metabolic disorders, elevated ceramides activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering cytokine release and contributing to neurotoxicity [23].

Table 1: Key Lipid Classes and Their Pathophysiological Roles

| Lipid Class | Change in Disease | Pathophysiological Role | Associated Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | Upregulated | Energy storage; source of pro-inflammatory free fatty acids | DM, HUA, CVD, MDD [3] [23] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | Upregulated | Membrane integrity; source of pro-inflammatory signaling lipids | DH, MDD [3] [23] |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | Upregulated/Downregulated (varies by species) | Membrane integrity; precursor to pro-inflammatory mediators | DH, MDD, CVD [3] [23] |

| Ceramides (Cer) | Upregulated | Promote insulin resistance, inflammation, and apoptosis | MDD, DM, CVD [23] |

| Lysophospholipids (e.g., LPC) | Upregulated | Promote monocyte migration and pro-inflammatory cytokine production | MDD [23] |

The diagram below illustrates the core pathological mechanisms linking lipid dysregulation to inflammation and organ damage in cardiometabolic and neurodegenerative diseases.

Remnant Cholesterol as a Novel Biomarker

Beyond specific lipid species, remnant cholesterol (RC)—the cholesterol content in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins—has emerged as a significant biomarker. In type 2 diabetes, elevated RC levels show a strong, independent positive correlation with hyperuricemia. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for RC in predicting HUA was 0.658, which was larger than those for LDL-C, TG, HDL-C, and TC, indicating its superior predictability [22]. This correlation is likely mediated through RC's association with low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance [22].

Table 2: Key Lipid Biomarkers in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Biomarker | Association/Change | Statistical Significance | Clinical/Pathological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remnant Cholesterol (RC) | Positive correlation with HUA in T2DM | OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.40–1.90; AUC = 0.658 [22] | Better predictor of HUA than conventional lipids; linked to inflammation |

| TG (16:0/18:1/18:2) | Significantly upregulated in DH vs. NGT | P < 0.05 [3] | Representative of dysregulated glycerolipid metabolism |

| PE (18:0/20:4) | Significantly upregulated in DH vs. NGT | P < 0.05 [3] | Involved in glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway disruption |

| Total Differential Lipids (DH vs. NGT) | 31 significant lipid metabolites | P < 0.05 [3] | Includes 13 TGs, 10 PEs, 7 PCs, 1 downregulated PI |

UHPLC-MS/MS Methodologies for Lipidomic Analysis

The application of UHPLC-MS/MS is critical for the precise identification and quantification of lipid species in metabolic disease research. The following section outlines standard protocols and workflows.

Sample Collection and Pre-processing

The following protocol is adapted from a study investigating lipidomics in diabetes and hyperuricemia [3]:

- Collection: Collect fasting blood samples (e.g., 5 mL) into appropriate anticoagulant tubes.

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Aliquoting: Transfer the upper plasma layer (e.g., 0.2 mL) into pre-labeled microcentrifuge tubes.

- Pooled QC: Create quality control (QC) samples by combining equal volumes of plasma from all sample groups.

- Storage: Store all samples at -80°C until analysis.

- Thawing: Thaw samples on ice and vortex thoroughly.

- Lipid Extraction: For a 100 μL plasma sample:

- Add 200 μL of ice-cold water and mix.

- Add 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol and mix.

- Add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and mix.

- Sonicate in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes.

- Let the mixture stand at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C.

- Organic Phase Collection: Collect the upper organic phase and dry under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent (e.g., 100 μL isopropanol) for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis.

UHPLC-MS/MS Instrumental Conditions

Chromatographic Conditions [3]:

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm length, 1.7 μm particle size).

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-water solution.

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-isopropanol solution.

- Gradient: A specific gradient elution program is used for optimal lipid separation.

Mass Spectrometric Conditions: While parameters vary, a comprehensive targeted method for 260 signaling lipids (including oxylipins, free fatty acids, and lysophospholipids) demonstrates the capability of UHPLC-MS/MS. Such methods are validated for parameters including linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), extraction recovery, matrix effect, and precision [24].

The typical workflow from sample to data is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (1.7 µm) | High-resolution separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to MS detection [3] |

| Lipid Extraction Solvent | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction, partitioning lipids from aqueous plasma samples [3] |

| Mass Spectrometry Standard | Deuterated Internal Standards (e.g., C15 Ceramide-d7, Stearic acid-d3) | Correct for matrix effects and variability in extraction efficiency; enable semi-quantification [25] |

| Mobile Phase Additive | Ammonium Formate | Volatile salt additive that improves ionization efficiency and aids in adduct formation (e.g., [M+NH4]+) in MS [3] |

| Quality Control Material | NIST Standard Reference Material 1950 | Pooled human plasma with certified/characterized values for inter-laboratory comparison and method validation [24] |

Lipid dysregulation is a cornerstone of pathophysiology in interconnected metabolic disorders such as diabetes and hyperuricemia. The specific upregulation of lipid classes like triglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and ceramides, along with perturbations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism, drives disease progression through inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance. The integration of advanced UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomics is pivotal for discovering these detailed mechanistic links and identifying novel biomarkers like remnant cholesterol. For researchers and drug developers, a standardized approach encompassing rigorous sample preparation, robust UHPLC-MS/MS protocols, and sophisticated data analysis is essential to translate these lipidomic insights into targeted therapeutic strategies and diagnostic tools, ultimately enabling a more personalized approach to patient care.

From Sample to Spectrum: A Practical UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics Workflow

Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, provides comprehensive analysis of lipid molecules within biological systems, offering profound insights into metabolic health and disease pathologies [12]. In the context of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HU), distinct lipidomic perturbations have been observed, revealing specific lipid signatures associated with these conditions [3]. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful analytical platform for lipidomic profiling due to its superior sensitivity, resolution, and capacity to identify and quantify hundreds of lipid species simultaneously [2].

The reliability of any lipidomic study hinges critically on the pre-analytical phase, particularly sample collection and lipid extraction. Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)-based extraction has gained prominence as a robust method for lipid recovery from plasma samples, offering several advantages over traditional chloroform-based methods [26] [27]. This technical guide provides an in-depth protocol for plasma collection and MTBE/methanol lipid extraction, contextualized within a research framework investigating lipidomic alterations in diabetes and hyperuricemia using UHPLC-MS/MS.

Plasma Collection and Pre-processing for Lipidomics

Proper collection and handling of plasma samples are paramount to preserving lipid integrity and ensuring analytically reproducible results.

Blood Collection and Processing

- Collection: Collect fasting blood samples (e.g., 5 mL) into appropriate anticoagulant tubes (e.g., lithium heparin or EDTA) [3] [28].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge blood samples at 3,000 rpm (approximately 2,000 × g) for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate cellular components from plasma [3].

- Aliquoting: Carefully transfer the upper plasma layer into clean tubes. For lipidomics, creating pooled quality control (QC) samples by combining equal aliquots from multiple subjects is recommended to monitor analytical performance [3] [29].

- Storage: Immediately freeze plasma aliquots at -80°C until lipid extraction. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles to prevent lipid degradation [3].

MTBE/Methanol Lipid Extraction Protocol

The MTBE method produces a biphasic system where lipids partition into the upper organic (MTBE) phase, while proteins and polar metabolites remain in the lower aqueous phase [26] [30]. This configuration allows for easy and quantitative recovery of the lipid-containing layer.

Detailed Step-by-Step Procedure

Table 1: Reagents and Equipment for MTBE Lipid Extraction

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Methanol (MeOH) | LC-MS grade, pre-cooled to 4°C |

| Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | HPLC or LC-MS grade |

| Water | MS-grade or deionized, LC-MS grade |

| Ammonium Formate | For mobile phase preparation in LC-MS |

| Plasma Sample | Thawed on ice |

| Centrifuge Tubes | 1.5 mL or 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes |

| Centrifuge | Capable of ≥ 13,000 × g |

| Nitrogen Evaporator | For gentle solvent drying under nitrogen stream |

| Vortex Mixer & Sonicator | For thorough mixing and cell disruption |

The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies [3] [26] [30]:

- Thawing: Thaw frozen plasma samples on ice or in a refrigerator at 4°C. Vortex briefly to ensure homogeneity.

- Aliquot Plasma: Pipette 100 μL of plasma into a 1.5 mL or 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Protein Precipitation: Add 200 μL of ice-cold methanol to the plasma aliquot.

- Vortex vigorously for 10-30 seconds to mix thoroughly. This step begins protein precipitation.

- Lipid Extraction: Add 800 μL of MTBE to the methanol-plasma mixture.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture for 1 hour at room temperature in a shaker to facilitate complete lipid extraction [26] [30].

- Phase Separation: Add 300 μL of MS-grade water to induce phase separation [30].

- Collection of Lipid Fraction: Carefully collect the upper organic (MTBE) layer without disturbing the intermediate pellet or lower aqueous phase.

- Solvent Evaporation: Evaporate the MTBE solvent to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas in a fume hood.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis, typically 100 μL of isopropanol or a mixture of chloroform-methanol-isopropanol (e.g., 1:2:4, v/v/v) [26]. Vortex thoroughly to ensure complete dissolution.

Diagram 1: MTBE Lipid Extraction Workflow (Total ~2.5 hours)

Application in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia Research

The MTBE extraction protocol effectively captures the lipid perturbations characteristic of diabetes and hyperuricemia. Applied to a study comparing patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), diabetes combined with hyperuricemia (DH), and healthy controls (NGT), this method enabled the identification of significant lipidomic differences [3].

Table 2: Significantly Altered Lipid Classes in Diabetes Mellitus with Hyperuricemia (DH) vs. Healthy Controls (NGT) [3]

| Lipid Class | Number of Significant Lipids | Trend in DH | Examples of Altered Lipids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | 13 | Significantly Upregulated | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2), etc. |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | 10 | Significantly Upregulated | PE(18:0/20:4), etc. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | 7 | Significantly Upregulated | PC(36:1), etc. |

| Phosphatidylinositols (PIs) | 1 | Downregulated | - |

Multivariate statistical analyses like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) of the extracted lipid data revealed a clear separation trend among the DH, DM, and NGT groups, confirming distinct lipidomic profiles [3]. Pathway analysis further demonstrated that glycerophospholipid metabolism and glycerolipid metabolism were the most significantly perturbed pathways in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia [3]. This lipidomic insight provides a metabolic basis for understanding the pathophysiology linking these two conditions.

Diagram 2: Research Context from Sample to Discovery

Comparative Performance and Considerations

The MTBE extraction method offers specific advantages for clinical lipidomics studies:

- High Lipid Recovery: Demonstrates similar or better recovery for most major lipid classes compared to traditional Folch or Bligh & Dyer methods [26].

- Practical Superiority: The upper organic phase is easier and safer to collect without disturbing the protein interphase, minimizing contamination [26] [27]. MTBE is also less toxic and hazardous than chloroform [26].

- Automation Compatibility: The protocol is amenable to automation using pipetting robots, enhancing throughput and reproducibility for large-scale clinical studies [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Reagent/Standard | Function/Application | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| SPLASH LIPIDOMIX | Quantification of diverse lipid classes via stable isotope-labeled internal standards | Pre-mixed solution from Avanti Polar Lipids [27] |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive for LC-MS; improves ionization and separation | LC-MS grade, 2-10 mM in water [3] [31] |

| UHPLC Columns | Chromatographic separation of complex lipid mixtures | e.g., Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 or HSS T3 columns [3] [31] |

| MTBE & Methanol | Primary solvents for lipid extraction; high purity critical | HPLC or LC-MS grade [26] [2] |

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) has become an indispensable tool in modern lipidomics, particularly in the study of complex metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH). The superior speed, resolution, and sensitivity of UHPLC compared to traditional HPLC make it ideally suited for unraveling the intricate lipid alterations characteristic of these conditions [32] [33]. Within the context of a broader thesis on UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic analysis in diabetes and hyperuricemia research, chromatography optimization is not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental requirement for generating biologically meaningful data.

The analysis of lipidomes in metabolic disorders presents unique challenges. Lipidomic studies in patients with DM and DH have revealed significant alterations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways [32]. These lipid classes encompass hundreds of molecular species with subtle structural differences, requiring chromatographic methods capable of high-resolution separations. The complexity of biological samples, containing diverse biomolecules with varying physicochemical properties, can lead to matrix effects and ion suppression, potentially masking critical lipid biomarkers [33]. Furthermore, the need for high-throughput analysis in large-scale epidemiological cohorts demands methods that balance comprehensive lipid coverage with reasonable analysis times [34].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of UHPLC optimization strategies specifically tailored for complex lipid separation in diabetes and hyperuricemia research. By integrating fundamental chromatographic principles with practical application guidelines, we aim to empower researchers to develop robust, reproducible, and informative lipidomic methods that can advance our understanding of the lipid basis of metabolic diseases.

Fundamental Principles of Lipid Separation by UHPLC

Chromatographic Basis for Lipid Class and Molecular Species Separation

The separation of lipids using UHPLC relies on the differential partitioning of lipid molecules between a stationary phase and a mobile phase. The two predominant separation mechanisms employed in lipidomics are reversed-phase (RP) and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC). RP-UHPLC, typically using C18 columns, separates lipids primarily based on their hydrophobicity, which is determined by acyl chain length, degree of unsaturation, and the number of acyl chains [2] [1]. This results in lipids eluting generally in order of increasing carbon number and decreasing double bonds within each lipid class.

HILIC separation, in contrast, operates on a different principle where lipids are separated based on the polarity of their head groups [35]. In HILIC mode, lipids from the same class elute together, which can minimize class-specific matrix effects and simplify data interpretation. The choice between these separation mechanisms depends on the specific research questions. For instance, when studying molecular species-level alterations in glycerophospholipids in diabetic patients, RP-UHPLC provides superior resolution, while HILIC may be preferable for class-level profiling [35].

The structural diversity of lipids necessitates careful optimization of chromatographic conditions to achieve optimal separation. For example, in diabetes and hyperuricemia research, the ability to resolve triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) – lipid classes frequently dysregulated in these conditions – is particularly important [32]. The presence of the vinyl ether bond in plasmalogens, which have antioxidant properties potentially relevant to oxidative stress in diabetes, further complicates separations and requires specific consideration [1].

Column Chemistry and Particle Technology

The selection of appropriate column chemistry is paramount for successful lipid separations. The majority of RP-UHPLC lipid analyses employ C18 columns with 1.7-2.0 μm particles, which provide an optimal balance of efficiency, pressure, and robustness [2] [1]. The particle technology significantly impacts separation efficiency, with sub-2μm particles being the standard for UHPLC applications, offering higher peak capacities and faster separations compared to conventional HPLC columns [33].

The column dimensions also play a crucial role in method performance. While 100-150 mm × 2.1 mm columns are common, longer columns can provide higher peak capacities for complex samples at the expense of analysis time and operating pressure [36]. The column temperature must be carefully optimized, as elevated temperatures (typically 40-60°C) enhance mass transfer and reduce mobile phase viscosity, leading to improved peak shapes, especially for late-eluting lipids like triglycerides and cholesteryl esters [1].

For specialized applications, alternative stationary phases may be beneficial. For instance, C8 columns can provide shorter analysis times for more polar lipids, while phenyl-hexyl columns offer different selectivity for lipids containing double bonds. In the context of diabetes and hyperuricemia research, where comprehensive lipid profiling is often desired, C18 columns generally provide the best compromise for broad lipid coverage [2].

Critical UHPLC Method Parameters and Optimization Strategies

Mobile Phase Composition and Gradient Optimization

The mobile phase system is a critical determinant of lipid separation efficiency and MS detection sensitivity. Typically, binary solvent systems are employed, consisting of water (aqueous phase) and organic solvents (organic phase). The aqueous phase often contains additives such as ammonium acetate (5-10 mM) or ammonium formate to enhance ionization efficiency and stabilize pH [2] [1]. The organic phase is commonly composed of acetonitrile, isopropanol, or mixtures thereof, with isopropanol being particularly effective for eluting very nonpolar lipids like triglycerides and cholesteryl esters [1].

Table 1: Mobile Phase Systems for Lipid Separation in UHPLC-MS/MS

| Component | Composition A (Aqueous) | Composition B (Organic) | Additives & Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | Water | Acetonitrile:Isopropanol (1:1) | - |

| Additives | 10 mM ammonium formate | 10 mM ammonium formate | Enhance ionization, adduct formation |

| Modifiers | 0.1% formic acid (optional) | 0.1% formic acid (optional) | Promote [M+H]+ formation in positive mode |

| Alternative | 10 mM ammonium acetate | Acetonitrile:Isopropanol (9:1) | - |

Gradient optimization is perhaps the most impactful parameter for controlling lipid separations. A well-designed gradient should provide adequate resolution of critical lipid pairs while maintaining reasonable analysis times. For comprehensive lipidomics, multi-segment gradients are often employed, starting with a high percentage of aqueous phase to retain polar lipids, followed by a shallow gradient segment to separate phospholipids, and a steeper segment to elute neutral lipids [1] [36]. The gradient profile must be optimized based on the specific lipid classes of interest. For diabetes and hyperuricemia research, where glycerophospholipids and glycerolipids are particularly relevant, gradients should be tailored to resolve these classes effectively [32].

Instrumental Parameters and Their Impact

The UHPLC system itself contributes significantly to method performance. Operating pressures in UHPLC typically range from 6000-15,000 psi, enabling the use of columns packed with sub-2μm particles [33] [36]. Flow rates generally fall between 0.2-0.6 mL/min for 2.1 mm id columns, balancing separation efficiency with analysis time. Lower flow rates can improve ionization efficiency in ESI-MS but extend analysis time, necessitating careful optimization based on research priorities.