Unveiling the Hidden: A Comprehensive Guide to Rare Cell Type Identification in Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to identify and characterize rare cell populations from single-cell RNA sequencing data.

Unveiling the Hidden: A Comprehensive Guide to Rare Cell Type Identification in Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to identify and characterize rare cell populations from single-cell RNA sequencing data. Covering the entire workflow from foundational concepts to advanced validation, we explore the critical biological importance of rare cells, benchmark specialized algorithms like scSID and CellSIUS against conventional methods, and detail best practices for data preprocessing, clustering optimization, and differential abundance analysis. A strong emphasis is placed on troubleshooting common pitfalls, such as the confounding effects of ambient RNA and batch effects, and on rigorous validation strategies to ensure biological relevance. By synthesizing current methodologies and practical solutions, this guide empowers discoveries in disease mechanisms, toxicology, and therapeutic development.

Why Rare Cells Matter: Biological Significance and Core Analytical Challenges

The human body is composed of an estimated 30 trillion cells, which operate both individually and collaboratively to maintain health and biological balance [1]. For centuries, cells have been recognized as the fundamental units of biological systems, yet their full complexity, particularly the existence and significance of rare cell populations, has only begun to emerge with recent technological advances [2] [3]. Rare cell types are typically defined as populations that constitute a small proportion (often 1-5%) of the total cells in a tissue or sample, such as dendritic cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [4]. These populations frequently drive disproportionately significant biological processes, including disease progression, drug resistance, tumor relapse, and key developmental transitions [4] [3].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our capacity to identify and characterize these rare populations by providing gene expression profiles at individual cell resolution [2] [5]. Unlike bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across thousands to millions of cells, scRNA-seq can detect cell subtypes or gene expression variations that would otherwise be overlooked, enabling the discovery of previously unknown and rare cell types [3] [5]. This technological advancement has transformed our understanding of cellular heterogeneity in complex biological systems, from immune function to cancer biology and developmental processes [2] [6].

The biological imperative to define rare cell types extends beyond mere cataloging. These populations often serve as critical regulators of physiological processes, contribute to pathological mechanisms when dysregulated, and may hold untapped potential for therapeutic intervention [7] [4]. In tumor microenvironments, for instance, rare cell populations can drive metastasis, mediate therapy resistance, and influence immune evasion [8] [6]. Similarly, in development, rare transitional states determine cell fate decisions and tissue patterning [3]. This article provides a comprehensive overview of methodologies for rare cell identification, analytical frameworks for interpretation, and applications across biomedical domains, with specific protocols and reagents to facilitate research in this rapidly advancing field.

Experimental Workflows: From Single-Cell Isolation to Sequencing

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture Technologies

The initial and most critical step in scRNA-seq involves extracting viable individual cells from tissues while preserving their transcriptional state [2] [5]. The selection of an appropriate isolation method significantly impacts cell viability, recovery, and transcriptional fidelity, particularly for fragile rare populations. The table below summarizes the primary technologies employed for single-cell isolation:

Table 1: Single-Cell Isolation and Capture Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Throughput | Key Applications | Considerations for Rare Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Hydrodynamic focusing with fluorescent detection and electrostatic droplet deflection [8] | High (up to 30,000 cells/sec) | Isolation of predefined rare populations; high-purity recovery [8] | Can be optimized for purity or yield; potential pressure damage to fragile cells [8] |

| Droplet-Based Microfluidics | Nanoliter-scale droplet encapsulation with barcoded beads [2] | Very High (thousands to millions of cells) | Unbiased profiling of complex tissues; rare cell discovery [2] [5] | Limited RNA capture efficiency; suitable for large cell numbers where rare types are present [2] |

| Microfluidic Microwells | Cell capture in nanowells with barcoded beads [5] | High (thousands to hundreds of thousands of cells) | Sensitive transcriptome capture; fixed tissue compatibility [5] | More sensitive than droplet methods for low-expression genes [2] |

| Laser Microdissection | UV laser cutting of specific cells from tissue sections [5] | Low (manual selection) | Spatial context preservation; morphology-based rare cell isolation [5] | Low throughput but enables selection based on visual characteristics |

| Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) | Magnetic bead separation using surface markers [5] | Moderate | Pre-enrichment before sequencing; depletion of abundant populations [5] | Lower resolution than FACS but gentler on cells; good for initial enrichment |

For tissues where dissociation is challenging or would induce significant stress responses, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides an alternative approach [2] [5]. This method sequences mRNA from isolated nuclei rather than intact whole cells, making it particularly applicable to frozen samples, neural tissues, and other difficult-to-dissociate tissues [5]. While snRNA-seq effectively minimizes artificial transcriptional stress responses, it only captures nuclear transcripts and may miss important biological processes related to cytoplasmic mRNA processing and metabolism [5].

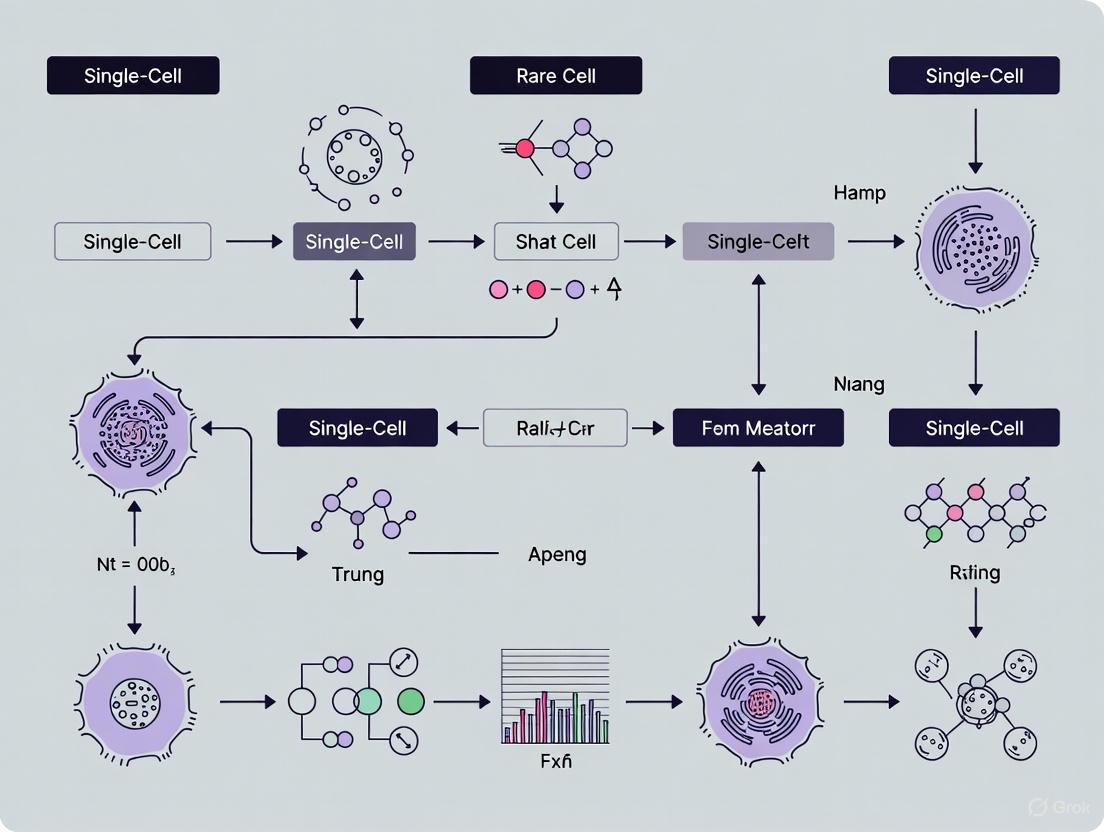

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points in sample preparation and single-cell isolation:

scRNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing Strategies

Following single-cell isolation, the conversion of cellular RNA into sequencer-compatible libraries involves several critical steps that influence the detection sensitivity for rare cell types [2] [5]. The core process includes cell lysis, reverse transcription (converting RNA to complementary DNA), cDNA amplification, and library preparation [2]. Two primary amplification strategies dominate current protocols:

PCR-based amplification (e.g., Smart-Seq2, MATQ-Seq): Utilizes polymerase chain reaction for non-linear amplification, often generating full-length or nearly full-length transcript coverage [2]. These methods excel in detecting more expressed genes and are advantageous for isoform usage analysis, allelic expression detection, and identifying RNA editing [2].

In vitro transcription (IVT) (e.g., CEL-Seq, MARS-Seq): Employs linear amplification through IVT, typically capturing only the 3' or 5' ends of transcripts [2]. While potentially introducing 3' coverage biases, these methods can be efficiently combined with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [2].

A critical innovation for accurate transcript quantification, particularly important for distinguishing rare cell types, is the implementation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [2] [5]. UMIs are short random nucleotide sequences that label each individual mRNA molecule during reverse transcription, enabling precise counting of original RNA molecules and eliminating PCR amplification bias [2] [5]. Protocols such as Drop-Seq, inDrop-Seq, 10x Genomics, and Seq-Well have incorporated UMIs to enhance quantitative accuracy [2].

The selection between full-length and 3'/5' end counting protocols represents a key strategic decision. Full-length methods (e.g., Smart-Seq2, MATQ-Seq) provide comprehensive transcript coverage, enabling isoform analysis and detection of low-abundance genes, while 3' end methods (e.g., Drop-Seq, 10x Genomics Chromium) typically offer higher throughput and lower cost per cell, making them suitable for analyzing larger cell numbers to capture rare populations [2].

Computational Analysis: Deciphering Rare Populations from scRNA-seq Data

Cell Type Annotation and Rare Population Identification

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data presents distinctive challenges, particularly for rare cell identification [4]. The high-dimensional, sparse, and noisy nature of single-cell gene expression data requires specialized analytical approaches [2] [4]. Cell type annotation - the process of categorizing and labeling cells based on their gene expression profiles - represents a critical step in uncovering rare populations [1].

Traditional annotation approaches rely on unsupervised clustering followed by manual labeling using known marker genes [4] [1]. While intuitive, this method suffers from several limitations for rare cell identification: dependence on prior knowledge of marker genes, inability to recognize novel cell types, and sensitivity to clustering parameters that may either obscure rare populations by merging them with abundant types or create artificial subdivisions [4].

Automated cell type annotation methods have emerged as powerful alternatives, employing machine learning classifiers trained on reference datasets to label query cells [4] [1]. These can be broadly categorized into:

- Traditional machine learning methods: Including support vector machine (SVM), random forest, and k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) [1]. Recent comparative studies indicate that SVM consistently outperforms other traditional techniques for cell annotation tasks [1].

- Deep learning approaches: Such as scBERT (adapted from BERT architecture) and scGPT (generative pre-trained transformer), which leverage pre-training on large-scale data to capture complex cellular relationships and mitigate batch effects [1].

- Hybrid methods: Combining supervised and unsupervised elements to improve accuracy, exemplified by tools like scClassify and CHETAH [1].

A fundamental challenge in rare cell type annotation is the imbalanced nature of scRNA-seq datasets, where classifiers tend to prioritize majority cell types at the expense of rare populations [4]. Innovative computational frameworks like scBalance specifically address this limitation by incorporating adaptive weight sampling and sparse neural networks to ensure rare cell types receive sufficient attention during classifier training without compromising accuracy for common populations [4].

Machine Learning Performance for Rare Cell Annotation

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Methods for Cell Type Annotation

| Method | Underlying Algorithm | Rare Cell Detection Performance | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | Support Vector Machine | Consistently top performer across multiple datasets [1] | High | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; robust to overfitting |

| Random Forest | Ensemble Decision Trees | Robust for major types, variable for rare populations [1] | Moderate | Handles complex patterns; provides feature importance |

| scBalance | Sparse Neural Network | Specifically optimized for rare cell identification [4] | High (GPU-accelerated) | Adaptive sampling for imbalanced data; scalable to million-cell datasets |

| k-NN | k-Nearest Neighbors | Moderate (depends on cluster density) | High with indexing | Simple implementation; effective with good reference data |

| Logistic Regression | Linear Classification | Good overall, second to SVM in some studies [1] | High | Interpretable model; fast training and prediction |

| Naive Bayes | Bayesian Probability | Least effective due to independence assumption [1] | High | Fast but limited by inaccurate feature independence assumption |

| Transformer Models | Self-Attention Mechanisms | Promising for complex patterns [1] | Variable (requires substantial resources) | Captures long-range dependencies in data |

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for rare cell identification, highlighting the specialized approaches required to address dataset imbalance:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Rare Cell Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Single-Cell Rare Cell Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Sorting Reagents | Fluorescently-labeled antibodies [8] | Marker-based cell identification and isolation | Critical for FACS; requires validation for rare cell surface targets |

| Single-Cell Library Prep Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium [2], SMART-Seq [2] | Single-cell RNA library construction | Determine 3' vs full-length based on study goals; consider UMI incorporation |

| Viability Stains | Propidium iodide, DAPI [8] | Exclusion of dead cells during sorting | Essential for preserving RNA quality and analysis accuracy |

| Cell Preservation Media | Cryopreservation solutions with DMSO | Maintain cell viability during storage | Particularly important for rare clinical samples |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Single-cell lysis and RNA capture buffers [5] | Nucleic acid isolation from single cells | Optimized for small input volumes; minimize contamination |

| Amplification Reagents | Template switching oligonucleotides [2] | cDNA amplification from single cells | Critical step influencing transcript detection sensitivity |

| UMI Barcodes | Cell and molecular barcodes [2] [5] | Unique labeling of cells and molecules | Enables accurate transcript counting and multiplexing |

| spatial Transcriptomics Reagents | Spatial barcoding oligonucleotides [3] | Preservation of spatial context in RNA sequencing | Emerging technology for situ rare cell analysis |

Applications and Protocols: Translating Discovery to Clinical Insight

Application Note 1: Rare Cell Dynamics in Tumor Microenvironments

Background: Tumor heterogeneity represents a fundamental challenge in oncology, with rare cell populations often driving metastasis, therapeutic resistance, and disease recurrence [2] [6]. ScRNA-seq has enabled unprecedented resolution of these rare populations within the complex tumor microenvironment [2].

Key Insights:

- Rare subpopulations of cancer stem cells exhibit distinct transcriptional programs that confer therapy resistance and metastatic potential [6]

- Immune cell diversity within tumors includes rare transitional states that modulate immunotherapy response [8]

- Cell-cell communication analysis through ligand-receptor pairing reveals how rare cells disproportionately influence tumor ecology [6]

Protocol: Identification of Rare Chemotherapy-Resistant Cells in Tumor Samples

- Sample Preparation: Obtain fresh tumor tissue via biopsy or resection. Using cold dissociation methods (4°C) to minimize stress-induced transcriptional artifacts [5]. Prepare single-cell suspension using gentle enzymatic digestion.

- Viability Staining: Incubate cells with viability dye (e.g., propidium iodide) for 15 minutes on ice to identify and exclude dead cells [8].

- FACS Enrichment: Sort live single cells using FACS with a nozzle size appropriate for the cell type (typically 100μm for tumor cells) [8]. Collect cells directly into lysis buffer.

- scRNA-seq Library Construction: Use a full-length transcript protocol (e.g., Smart-Seq2) for comprehensive transcriptome coverage of rare populations [2]. Incorporate UMIs for accurate transcript quantification.

- Sequencing: Sequence to sufficient depth (minimum 50,000 reads per cell) to detect low-abundance transcripts characteristic of rare states.

- Computational Analysis: Process data using scBalance or similar imbalance-aware classifiers [4]. Conduct trajectory inference to identify transitional states and resistance pathways.

Application Note 2: Rare Immune Cell Populations in COVID-19 Pathogenesis

Background: The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 involves complex cellular interactions, with rare immune subsets potentially driving pathological inflammation or protective immunity [4]. A recent COVID-19 immune cell atlas profiled 1.5 million cells, revealing previously unappreciated rare populations [4].

Key Insights:

- Rare dendritic cell subsets show distinct antigen presentation capacity correlated with disease severity [4]

- Transitional T cell states exhibit inflammatory gene signatures associated with cytokine storm [4]

- Neutrophil heterogeneity includes rare subsets with pathogenic potential in severe infection [4]

Protocol: High-Throughput Profiling of Rare Immune Cells in PBMCs

- Sample Collection: Collect peripheral blood in anticoagulant tubes. Isolate PBMCs using density gradient centrifugation within 2 hours of collection.

- Cell Staining: Stain with antibody panels for surface markers without disrupting cell integrity.

- Droplet-Based scRNA-seq: Use high-throughput droplet methods (e.g., 10x Genomics) to profile 50,000-100,000 cells per sample [2]. Include hashtag antibodies for sample multiplexing.

- Library Preparation: Follow manufacturer protocol with emphasis on UMI incorporation to control for amplification bias [2] [5].

- Sequencing: Perform 3' end sequencing with moderate depth (20,000-50,000 reads per cell) to balance cost and rare cell detection.

- Analysis: Implement scBalance for rare population identification [4]. Use differential expression analysis to characterize rare cell-specific markers. Validate findings using FACS isolation and functional assays.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of rare cell biology stands at a transformative juncture, with several emerging technologies poised to address current limitations. Multi-omics approaches that simultaneously profile transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic features from the same single cells will provide unprecedented insights into the regulatory mechanisms defining rare populations [7] [9]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning will further enhance rare cell detection, with predictive models forecasting disease progression and treatment responses based on rare cell dynamics [7].

Spatial transcriptomics represents another frontier, enabling the mapping of rare cells within their native tissue architecture to understand positional relationships and neighborhood effects [3]. This is particularly valuable for contextualizing how rare cells influence their local microenvironments and vice versa. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly enable the construction of comprehensive cellular atlases across development, health, and disease [3] [5].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in reducing the specialized expertise and costs associated with single-cell technologies to broaden their accessibility [3]. Standardization of analytical approaches and validation frameworks will be essential for translating rare cell discoveries into clinical applications [7]. The ongoing development of closed, automated systems for cell processing and analysis will facilitate the transition of these technologies into clinical diagnostics and monitoring [8].

In conclusion, defining rare cell types represents both a biological imperative and a technological achievement. These rare populations, though small in number, hold profound significance for understanding health and disease mechanisms. The continued refinement of single-cell technologies, computational frameworks, and integrative approaches will undoubtedly uncover new rare cell types and states, expanding our fundamental understanding of biology and opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention across a spectrum of human diseases.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, yet significant data science challenges impede its full potential, particularly in identifying rare cell types crucial for disease pathogenesis and therapeutic development. This Application Note delineates the central obstacles of technical noise and data sparsity inherent in single-cell technologies and elucidates how conventional clustering methods fail to resolve rare cell populations. We provide a structured comparison of computational strategies and detailed protocols for employing advanced algorithms that overcome these limitations, enabling robust rare cell identification. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this document serves as a guide for refining single-cell analytical workflows to uncover biologically significant, low-abundance cell types.

The transition from bulk to single-cell transcriptomics has unveiled a complex landscape of cellular heterogeneity, fundamentally altering our approach to biological investigation and therapeutic target discovery [10]. However, this high-resolution view comes with considerable data science challenges. The foundational step of most scRNA-seq analyses—clustering cells based on gene expression profiles—is critically undermined by technical noise and extreme data sparsity when the goal is to identify rare cell types, which may constitute less than 1% of a sample [11] [12].

Conventional clustering algorithms, such as those implemented in widely-used toolkits, perform well for distinguishing abundant cell types but systematically overlook rare populations. These rare types are often lost within larger clusters or misinterpreted as outliers due to their low numbers and the high stochasticity of gene expression measurements at single-cell resolution [13] [11]. This limitation is non-trivial, as rare cells like circulating tumor cells, progenitor cells, or unique immune subtypes often hold paramount importance in understanding disease mechanisms and progression [11]. This note details the specific causes of these analytical pitfalls and provides validated protocols and tools to navigate them effectively.

Core Challenges in the Data Landscape

Technical noise in scRNA-seq data arises from the minimal starting material and the complex, multi-step experimental protocol, which introduces variability that can obscure genuine biological signals.

- Amplification Bias and Low RNA Input: The low quantity of RNA from a single cell requires amplification, a process fraught with stochasticity. This leads to uneven representation of transcripts, skewing the apparent abundance of specific genes and contributing to technical noise that is particularly detrimental for quantifying low-abundance transcripts [13] [12].

- Dropout Events: A predominant source of noise and sparsity is the "dropout" phenomenon, where a transcript is present in a cell but fails to be captured or amplified, resulting in a false-zero measurement. Dropouts are more frequent for genes with low to moderate expression levels, directly complicating the identification of rare cell types that may rely on such genes as markers [13].

- Batch Effects: Technical variations between different sequencing runs, reagents, or operators introduce systematic differences in gene expression profiles. These batch effects can confound biological analysis, making it difficult to distinguish a genuine rare population from a technical artifact [13] [10].

Data Sparsity: A Fundamental Constraint

The sparsity of scRNA-seq data, characterized by an excess of zero counts, has been a central focus of computational method development. As sequencing technologies have evolved to capture millions of cells per experiment, the data have become progressively sparser [14]. This sparsity is a compound issue:

- Biological Zeros: Represent the true absence of a transcript in a cell.

- Technical Zeros: Represent dropout events, where a transcript was present but not measured. Critically, all zeros in scRNA-seq data carry biological significance; even a technical zero indicates that a gene is unlikely to be highly expressed, information that can be leveraged in analysis [14].

Why Conventional Clustering Fails for Rare Cells

Standard clustering workflows often rely on global, high-variance genes to project cells into a low-dimensional space where clustering is performed. This approach is inherently biased toward the majority cell population.

- Resolution Limit: The high dimensionality and noise can cause rare cells to be "absorbed" into larger, transcriptionally similar clusters, rendering them invisible [11].

- Feature Selection Bias: The genes that are most variable across the entire dataset are often not the markers that define a rare population. Consequently, the features selected for clustering may contain little to no information to distinguish the rare cells [15] [16].

Table 1: Core Data Challenges and Their Impact on Rare Cell Identification

| Challenge | Primary Cause | Impact on Rare Cell Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Noise | Amplification bias, stochastic capture, batch effects | Obscures the genuine gene expression signal of rare cells, making them appear as outliers or technical artifacts. |

| Data Sparsity | Low RNA input, dropout events, increasing cell numbers per experiment | Creates an abundance of zeros, complicating the distinction between true absence of expression and failed detection of key marker genes. |

| Conventional Clustering | Reliance on global highly variable genes, resolution limits | Fails to separate rare cells, which are either grouped into larger clusters or discarded as noise during quality control. |

Overcoming the Limits: Advanced Methodologies

To address the failures of conventional clustering, several advanced computational methods have been developed specifically for rare cell detection. They can be broadly categorized by their underlying strategy.

Cluster Decomposition and Anomaly Detection

The scCAD (Cluster decomposition-based Anomaly Detection) method iteratively refines clustering to isolate rare populations.

- Principle: Instead of one-time global clustering, scCAD performs an ensemble feature selection to preserve differential signals of rare types. It then iteratively decomposes major clusters based on the most differential signals within each cluster. Finally, it uses an isolation forest model on candidate marker genes to calculate an anomaly score and identify rare clusters [11].

- Advantage: It does not rely on pre-defined clusters or assume that rare cells form distinct clusters in the initial global analysis, making it highly robust.

Cluster-Independent Marker Gene Identification

The CIARA (Cluster Independent Algorithm for the identification of markers of RAre cell types) algorithm identifies potential rare cell markers prior to clustering.

- Principle: CIARA selects genes that are likely to be markers of rare cell types based on their expression patterns, independent of any cluster labels. These genes are then integrated with common clustering algorithms to single out groups of rare cells [15].

- Advantage: It bypasses the bias introduced by initial clustering, allowing for the discovery of rare populations that would otherwise be missed.

Feature Selection Based on Gene Expression Distribution

The GiniClust family of methods uses the Gini index, a statistical measure of inequality, to select genes for clustering.

- Principle: The Gini index is effective at identifying genes with highly variable expression that are specific to a small subset of cells (a pattern typical of rare cell type markers). Clustering is then performed based on these "high-Gini" genes [16].

- Advantage: It directly targets genes with expression patterns characteristic of rare cell types, improving sensitivity.

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Methods for Rare Cell Identification

| Method | Underlying Strategy | Key Feature | Reported Performance (F1 Score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| scCAD [11] | Iterative cluster decomposition & anomaly detection | Ensemble feature selection; does not rely on initial clustering | 0.4172 (benchmarked on 25 datasets) |

| CIARA [15] | Cluster-independent marker identification | Identifies rare cell marker genes prior to any clustering | Outperforms existing methods (specific F1 not provided) |

| GiniClust3 [16] | Gini-index-based feature selection | Uses Gini index to find genes associated with rare subsets; memory-efficient for large datasets | Superior to standard clustering for rare cells (specific F1 not provided) |

| Binary Analysis [14] | Binarization of expression data (0 vs non-0) | Treats all zeros as biologically meaningful; reduces computational cost | Comparable results to count-based analysis for cell type ID |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Rare Cell Identification using scCAD

The following workflow is adapted from the methodology detailed by [11].

I. Prerequisites and Data Preprocessing

- Input Data: A processed gene expression matrix (cells x genes) following standard scRNA-seq preprocessing.

- Software: Install the scCAD package (implementation available from the authors upon publication).

- Quality Control: Perform standard QC to remove low-quality cells (high mitochondrial percentage, low gene counts) using tools like Seurat or Scanpy [17].

- Normalization: Normalize the data using a method like log(TPM+1) or SCTransform.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Ensemble Feature Selection: Run the initial feature selection module of scCAD. This step combines genes from initial clustering labels and a random forest model to create a robust set of features that maximize the preservation of differential signals.

- Iterative Cluster Decomposition:

- The algorithm will perform an initial clustering (I-clustering) based on global gene expression.

- It will then iteratively decompose each resulting cluster based on the most differential signals within that cluster, generating decomposed clusters (D-clusters).

- Cluster Merging: To improve computational efficiency, the D-clusters are merged based on the closest Euclidean distance between their centers, resulting in a set of merged clusters (M-clusters).

- Anomaly Scoring and Rare Cluster Identification:

- For each M-cluster, perform differential expression analysis to identify a cluster-specific candidate gene list.

- Apply an isolation forest model using this gene list to calculate an anomaly score for every cell.

- Compute an "independence score" for each cluster by assessing the overlap between cells with high anomaly scores and the cells within the cluster.

- Clusters with the highest independence scores are flagged as potential rare cell populations.

III. Validation and Downstream Analysis

- Validate the identity of the putative rare cells by examining the expression of known marker genes from the literature.

- Perform differential expression analysis between the rare population and all other cells to identify novel marker genes.

- Use functional enrichment analysis (e.g., GSEA) on the differentially expressed genes to infer the biological role of the rare population.

scCAD Rare Cell Identification Workflow: This diagram outlines the key computational steps, from data preprocessing to the final validation of identified rare cell clusters.

Protocol 2: Leveraging Binarized Data for Efficient Analysis

For extremely large datasets (e.g., >1 million cells), where computational resources are a constraint, a binarized analysis can be highly effective [14].

I. Data Binarization

- Transform the normalized count matrix into a binary matrix, where

0represents a zero count and1represents any non-zero count.

II. Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering on Binary Data

- Apply dimensionality reduction techniques designed for or compatible with binary data, such as:

- scBFA: A factor analysis method for binary single-cell data.

- PCA on Binary Matrix: Standard PCA can be applied to the binary matrix.

- Jaccard Similarity Matrix: Calculate the Jaccard index between cells and use its eigenvectors for reduction.

- Use the resulting low-dimensional embeddings for clustering and UMAP/t-SNE visualization. Cell type identification can be performed using detection-based marker genes or classifier training on the binarized data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

A robust rare cell analysis pipeline relies on both wet-lab reagents and specialized computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent and Software Solutions

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) [13] | Tags individual mRNA molecules to correct for amplification bias and quantify absolute transcript counts. | Critical for accurate quantification, especially for low-abundance transcripts in rare cells. |

| ERCC Spike-in RNAs [12] | Exogenous RNA controls added in known quantities to model technical noise and quantify capture efficiency. | Allows for probabilistic decomposition of technical and biological variance. |

| Cell Hashing [13] | Uses oligonucleotide-labeled antibodies to multiplex samples, identifying doublets and improving sample demultiplexing. | Reduces misidentification of cell doublets as rare cell types. |

| 10x Genomics Visium [13] | Combines spatial transcriptomics with scRNA-seq, providing spatial context for identified rare cells. | Validates the spatial location and cellular microenvironment of rare populations. |

| scCAD Software [11] | Cluster decomposition-based anomaly detection algorithm for rare cell identification. | The method of choice for complex datasets where rare types are obscured in initial clustering. |

| GiniClust3 Software [16] | A fast, memory-efficient tool for rare cell identification using the Gini index for feature selection. | Suitable for analyzing very large datasets (over 1 million cells). |

| CIARA Software [15] | Cluster-independent algorithm for identifying markers of rare cell types. | Use when prior knowledge suggests a rare population that standard clustering consistently misses. |

| cellxgene Visualization Tool [18] | An open-source interactive tool for visual exploration of single-cell datasets. | Essential for researchers to intuitively validate and interpret computational findings. |

The journey to reliably identify rare cell types is fraught with challenges stemming from the fundamental nature of single-cell data. Technical noise and extreme sparsity create a landscape where conventional analytical tools are insufficient. However, as outlined in this Application Note, a new generation of sophisticated computational strategies—such as iterative cluster decomposition, cluster-independent marker discovery, and efficient binarized analysis—provides a powerful arsenal to overcome these limits. By integrating these specialized protocols and tools into their research workflows, scientists and drug developers can now systematically uncover critical, yet elusive, rare cell populations, thereby unlocking deeper insights into biology and disease.

The identification and characterization of rare cell populations represents a fundamental challenge and opportunity in single-cell biology. These rare populations—including stem cells, transient developmental states, drug-resistant clones, and rare immune cell subsets—play disproportionately important roles in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis [19]. While single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to profile cellular heterogeneity, standard analytical workflows demonstrate systematic failures when applied to rare cell types that constitute less than 1% of a population [20] [21]. This methodology gap has profound implications for both basic research and drug development, potentially obscuring biologically and clinically critical cell states from discovery. This Application Note details the systematic benchmarking evidence revealing this gap and provides validated experimental and computational protocols to address it.

Benchmarking Evidence: Documenting the Methodology Gap

Comprehensive benchmarking studies using datasets with known cellular composition have quantitatively demonstrated that most standard clustering methods fail to identify rare cell populations.

Performance Failure with Rare Populations

Table 1: Performance of Clustering Methods on Rare Cell Populations (<1% abundance)

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Performance on Abundant Cell Types | Performance on Rare Cell Types (<1%) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k-means based | SC3, pcaReduce | High (ARI >0.95) | Poor (ARI declines to 0.69-0.85) | Merges rare cells with abundant populations |

| Hierarchical | hclust | High (ARI 0.98) | Moderate (ARI 0.98)* | Classifies rare cells as outliers |

| Density-based | DBSCAN | High | Moderate (ARI 0.99)* | Identifies rare cells only as "border points" |

| Graph-based | Seurat | High (ARI >0.95) | Poor (ARI declines to 0.76) | Merges rare cells with abundant populations |

| Rare cell-specific | CellSIUS, MarsGT | High | High (F1 score >0.9) | Specifically designed for rare population identification |

Note: ARI (Adjusted Rand Index) measures agreement with known labels; values closer to 1 indicate better performance. *While hclust and DBSCAN maintain higher ARI, they fail to properly classify rare cells as distinct populations, instead identifying them as outliers [20].

In one systematic benchmark using a dataset of ~12,000 single-cell transcriptomes from eight human cell lines with known composition, all standard clustering methods failed to identify rare cell populations containing only 0.08-0.15% of total cells [20]. Similarly, a 2025 benchmark of 28 clustering algorithms confirmed that methods designed for abundant cell types consistently underperform for rare populations, particularly with complex samples like tumor biopsies [22].

Multi-omics Benchmarking Reveals Consistent Gaps

Table 2: Benchmarking Results Across Single-Cell Modalities

| Evaluation Metric | Transcriptomic Data (Top Performer) | Proteomic Data (Top Performer) | Multi-omics Data (Top Performer) | Rare Cell Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | scDCC, scAIDE, FlowSOM | scAIDE, scDCC, FlowSOM | MarsGT, cell2location, RCTD | MarsGT specifically designed for rare cells |

| Rare Cell Detection (F1 Score) | 0.45-0.65 (general methods) | 0.40-0.60 (general methods) | 0.85-0.95 (MarsGT) | MarsGT outperforms on 550 simulated datasets |

| Affected Factors | Highly abundant cell types mask rare populations | Limited feature dimensions challenge rare type identification | Complementary signals improve detection | Performance decreases with extremely rare types (<0.5%) |

The performance gap is particularly pronounced in complex biological samples where rare populations may be transcriptionally similar to abundant ones. In spatial transcriptomics benchmarking, nearly all deconvolution methods showed significantly decreased performance for detecting rare cell types, with simple regression models surprisingly outperforming almost half of dedicated spatial deconvolution methods [23].

Experimental Protocols for Rare Cell Identification

CellSIUS Protocol for Rare Cell Detection

CellSIUS (Cell Subtype Identification from Upregulated gene Sets) was specifically developed to fill the methodology gap for rare cell population identification [20].

Figure 1: CellSIUS Workflow for Rare Cell Identification

Step-by-Step Protocol

Input Data Preparation

- Process scRNA-seq data through standard quality control and normalization pipelines

- Remove low-quality cells and genes with minimal expression

- Critical: Retain all cells, including potential rare populations, during filtering

Initial Coarse Clustering

- Perform standard clustering (Seurat, SC3, etc.) at low resolution to identify major cell types

- Use visualization (UMAP/t-SNE) to confirm capture of major populations

- Output: Preliminary cell type assignments

Candidate Gene Identification within Clusters

- For each coarse cluster, identify genes with bimodal expression patterns

- Select genes showing upregulated expression in small cell subsets

- Parameters: Minimum 5 cells expressing candidate gene, expression >2-fold higher than cluster mean

Cell Subsetting and Gene Filtering

- Subset cells expressing each candidate gene

- Apply secondary filtering to remove genes with broad expression across clusters

- Validation: Confirm candidate genes show restricted expression patterns

Signature Refinement and Rare Population Calling

- Aggregate cells from related candidate genes into potential rare populations

- Apply statistical thresholds to define final rare populations

- Output: Rare cell populations with signature gene lists

Validation and Interpretation

- Compare CellSIUS-identified populations with known marker genes

- Validate findings using orthogonal methods (FISH, flow cytometry)

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on signature genes

MarsGT Protocol for Multi-omics Rare Cell Detection

MarsGT (Multi-omics analysis for rare population inference using single-cell Graph Transformer) leverages multi-omics data and graph neural networks for enhanced rare cell identification [21].

Figure 2: MarsGT Multi-omics Rare Cell Detection Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol

Multi-omics Data Processing

- Process paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data through modality-specific quality control

- Perform integration using established multi-omics integration methods

- Input Requirements: Matched cells across modalities or effective integration

Heterogeneous Graph Construction

- Construct graph with three node types: cells, genes, and peaks

- Create edges based on gene expression in cells and peak accessibility in cells

- Parameters: Include peak-gene links based on regulatory potential

Probability-based Subgraph Sampling

- Calculate selection probability for genes/peaks based on specificity

- Prioritize rare-related features with high expression in target cells and low expression elsewhere

- Key Innovation: Sampling strategy highlights rare cell-specific features

Graph Transformer Embedding

- Apply multi-head attention mechanism to update joint embeddings

- Iteratively refine cell, gene, and peak representations

- Output: Unified embedding space capturing multi-omics relationships

Joint Clustering and Regulatory Analysis

- Predict cell assignment probability matrix

- Simultaneously predict peak-gene link assignment probability

- Output: Rare cell populations with enhancer-gene regulatory networks (eGRNs)

Validation and Application

- Benchmark against known rare populations in simulation datasets

- Validate regulatory predictions using external chromatin interaction data

- Apply to biological questions requiring rare population identification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Rare Cell Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Technology | Application in Rare Cell Research | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell Platform | 10X Genomics Chromium | High-throughput scRNA-seq of heterogeneous samples | Captures thousands of cells, commercial reliability | Cell viability critical for recovery of rare types |

| Fluidigm C1 | Low-to-medium throughput with high sensitivity | Enhanced detection of low-expression genes | Limited to hundreds of cells | |

| Dolomite Bio μEncapsulator | Droplet-based single-cell isolation | Customizable workflows | Requires technical expertise | |

| Library Preparation | SMARTer (Clontech) | mRNA capture and cDNA amplification | High efficiency for low-input samples | Optimized for polyA+ RNA |

| Nextera XT (Illumina) | Library preparation for sequencing | Fast workflow, low input requirements | Potential amplification bias | |

| Cell Isolation | FACS (Fluorescence-activated cell sorting) | Pre-enrichment of rare populations | High purity, multi-parameter sorting | Requires known surface markers |

| Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) | Depletion of abundant populations | Rapid processing, gentle on cells | Limited multiplexing capability | |

| Computational Tools | CellSIUS | Rare cell identification from scRNA-seq | No prior knowledge required, identifies signature genes | Requires coarse clustering first |

| MarsGT | Multi-omics rare cell detection | Integrates scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq | Computationally intensive | |

| cell2location | Spatial mapping of rare cells | Resolves rare populations in spatial data | Requires reference scRNA-seq | |

| Validation Reagents | RNAscope (ACD Bio) | Single-molecule RNA FISH validation | High specificity and sensitivity | Requires optimization for tissue types |

| Cite-seq antibodies | Protein validation of transcriptomic findings | Multi-modal validation at single-cell level | Limited to surface proteins |

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

Practical Considerations for Experimental Design

- Cell Number Requirements: For rare populations comprising <1% of total cells, aim for minimum of 10,000 cells to ensure sufficient representation of rare types

- Replication: Include biological replicates to distinguish technical artifacts from true rare populations

- Controls: Spike-in cells of known identity when possible to validate detection sensitivity

- Multi-omics Integration: When possible, employ multi-omics approaches as MarsGT demonstrates 30-50% improvement in rare cell detection F1 scores compared to transcriptome-only methods [21]

Troubleshooting Common Issues

False Positive Rare Populations:

- Cause: Technical artifacts or doublets

- Solution: Validate using marker genes and cross-dataset comparisons

- Protocol Modification: Implement doublet detection algorithms and remove low-quality cells more stringently

Failure to Detect Known Rare Populations:

- Cause: Insufficient sequencing depth or cell numbers

- Solution: Increase sequencing depth to >50,000 reads/cell and increase total cell numbers

- Protocol Modification: Employ targeted enrichment or oversampling of specific cell subsets

Inconsistent Results Across Methods:

- Cause: Different algorithmic assumptions and sensitivity

- Solution: Use consensus approaches and orthogonal validation

- Protocol Modification: Implement multiple rare cell detection algorithms and compare results

The systematic failure of standard clustering methods on rare cell populations represents a significant methodology gap in single-cell genomics. Through rigorous benchmarking, this gap has been quantitatively documented, with rare cell-specific tools like CellSIUS and MarsGT demonstrating superior performance for identifying these biologically critical populations. The protocols detailed herein provide researchers with validated workflows to overcome this limitation, enabling more comprehensive characterization of cellular heterogeneity in development, disease, and therapeutic contexts. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, the development of methods specifically designed for rare population analysis will remain essential for fully exploiting the potential of single-cell genomics in biomedical research and drug development.

Specialized Algorithms and Workflows for Sensitive Rare Cell Detection

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the study of cellular heterogeneity, enabling the transcriptional profiling of individual cells within complex tissues [24] [25]. A significant application of this technology is the identification of rare cell populations, which are biologically crucial but often constitute a very small fraction of the total cellular material. Examples include cancer stem cells that drive tumorigenesis and therapy resistance, antigen-specific T cells essential for immunological memory, and endothelial progenitor cells involved in angiogenesis [24] [26] [27]. Despite their low abundance, these cells play pivotal roles in health and disease, making their accurate identification a priority in biomedical research.

However, rare cell types present a particular challenge for standard unsupervised clustering methods, which tend to focus on major populations and often absorb rare cells into more prevalent clusters [20] [28]. This methodology gap has spurred the development of dedicated algorithms designed specifically for the sensitive and specific discovery of rare cells. This article details the principles, application, and experimental protocols for three such tools: scSID, CellSIUS, and Rarity. These algorithms employ distinct strategies—similarity partitioning, upregulated gene set analysis, and Bayesian latent variable modeling, respectively—to overcome the limitations of conventional clustering in the context of rare cell identification.

Algorithm Principles and Workflows

scSID (single-cell similarity division)

The scSID algorithm is motivated by the principle that cells of the same type exhibit high intercellular similarity in gene expression space. Its design addresses the limitations of methods that rely on bimodal gene distributions or preliminary clustering, which can miss rare populations with low differential gene expression [24].

The algorithm operates in two main phases:

- Phase 1: Cell division based on individual similarity. scSID performs principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality. For each cell, it calculates the Euclidean distance to its K nearest neighbors (KNN). A key observation is that for a rare cell, the first k neighbors will show high similarity (small distances), but the distance will increase significantly beyond these initial neighbors. scSID captures this change using the first-order difference of the distances to the KNNs to characterize each cell [24].

- Phase 2: Rare cell detection based on population similarity. This step mitigates the impact of noise and outliers from the first step. It employs a step-by-step clustering synthesis to explore hierarchical relationships between cells within the identified groups and their external nearest neighbors, ultimately delineating the rare cell populations [24].

Workflow of the scSID algorithm for rare cell identification.

CellSIUS (Cell Subtype Identification from Upregulated gene Sets)

CellSIUS is designed to fill a methodology gap for the specific and selective identification of rare cell populations and their transcriptomic signatures. It is designed to be used in a two-step approach following an initial coarse clustering of major cell types [20].

Its workflow proceeds as follows:

- Step 1: Identification of candidate marker genes. Within each pre-defined major cluster, CellSIUS identifies genes that are upregulated in a small subset of cells compared to the rest of the cluster. It screens for genes exhibiting a bimodal distribution of expression [20].

- Step 2: Formation of rare sub-clusters. For each candidate gene, the subpopulation of cells with high expression is identified. These cells are then subjected to one-dimensional clustering based on the bimodal distribution of the marker gene to define a distinct rare subpopulation [20]. CellSIUS simultaneously reveals transcriptomic signatures indicative of the rare cell type's function.

Workflow of the CellSIUS algorithm for rare cell identification.

Rarity

Rarity is a hybrid semi-supervised framework developed to provide user-controlled sensitivity to rare subpopulations, including those differing from other cells by the expression of only a small number of markers. It addresses the failure of common unsupervised methods to reliably detect rare populations [28] [29].

The core principle of Rarity is a Bayesian latent variable model:

- Binary Latent States: Rarity conditions on the assumption that continuous marker expression values have an underlying binary on/off state. These unobserved states are modeled as binary latent variables [28].

- Cluster Assignment: Every cell with the same binary signature across all features is assigned to the same cluster. The cluster space encompasses all possible 2^P combinations of on/off states, where P is the number of features [28].

- Integration of Known Information: Known cell types can be specified a priori by defining their expected binary expression pattern, allowing Rarity to function in a semi-supervised manner. The model is implemented within a variational autoencoder framework, which ensures scalability to large numbers of cells [28].

Workflow of the Rarity algorithm for rare cell identification.

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

A critical step in method selection is understanding the relative performance of different algorithms. Benchmarking studies using datasets with known cellular composition provide valuable insights into the sensitivity, specificity, and scalability of these tools.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Rare Cell Identification Algorithms

| Feature | scSID | CellSIUS | Rarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Similarity partitioning using KNN | Identification of upregulated gene sets within major clusters | Bayesian latent binary state model |

| Requires Initial Clustering | No | Yes | No |

| Primary Output | Rare cell clusters | Rare subpopulations and their signature genes | Rare cell clusters with binary signatures |

| Handles Large Datasets | Yes, memory efficient | Performance depends on initial clustering | Yes, uses variational autoencoder for scalability |

| Key Advantage | Exceptional scalability & speed; direct rare cell detection | High specificity & selectivity; functional signature output | Sensitivity to small expression differences; interpretable binary profiles |

Benchmarking on Synthetic and Mixed Cell Line Data

Benchmarking often involves datasets where rare cells are artificially introduced or whose identity is known, allowing for the calculation of accuracy metrics like the F1 score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall).

- FiRE vs. scSID, CellSIUS, and others: In a simulation where Jurkat cells were bioinformatically diluted to 2.5% within a background of 293T cells, FiRE (Finder of Rare Entities, another algorithm) demonstrated a higher F1 score compared to GiniClust, RaceID, and the general outlier method LOF [26]. While a direct comparison between scSID, CellSIUS, and Rarity was not available in the search results, scSID has been shown to outperform existing methods, including RaceID and GiniClust, on various experimental datasets in terms of efficiency [24].

- CellSIUS Performance: CellSIUS outperformed existing algorithms in both specificity and selectivity for rare cell type identification in synthetic and complex biological data [20]. In a benchmark dataset of ~12,000 single-cell transcriptomes from eight human cell lines, standard clustering methods failed to identify cell types with abundances below 1%, whereas CellSIUS successfully detected them [20].

- Rarity's Self-Consistency: Rarity's performance was evaluated using metrics of self-consistency: conditional homogeneity (a cluster contains only one cell type) and conditional completeness (all cells of a type are in one cluster). In downsampling experiments, existing unsupervised methods failed to reliably re-identify rare populations, whereas Rarity maintained robust performance [28].

Table 2: Representative Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

| Algorithm | Dataset | Rare Population | Key Performance Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| scSID | Multiple experimental datasets (68K PBMC, intestine) | Various rare types | Outperformed existing methods (e.g., RaceID) in efficiency; showed exceptional scalability and memory efficiency [24] |

| CellSIUS | ~12k cell line benchmark | Cell types at <1% abundance | Correctly identified rare populations where standard clustering methods (SC3, Seurat, etc.) failed [20] |

| Rarity | (Semi-)synthetic IMC data | Downsampled clusters | Achieved high conditional homogeneity and completeness scores, demonstrating reliable re-discovery of rare types after downsampling [28] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing the aforementioned algorithms in a research setting, from cell preparation to computational analysis.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Single-Cell Rare Cell Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput single-cell partitioning & barcoding | Widely used droplet-based platform [20] [27] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Isolation of specific or rare cells from a heterogeneous suspension | Enables precise optical marking and sorting [27] [25] |

| Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) | Magnetic bead-based isolation of target cells | Useful for pre-enrichment; less stressful on cells [30] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Buffer additive to minimize cell loss and aggregation | Used at 0.1-1% in PBS to maintain cell viability [30] |

| DNAse I | Enzyme to reduce cell clumping by digesting extracellular DNA | Critical for samples that have undergone lysis [30] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short barcode sequences attached to transcripts | Allows accurate quantification by correcting for amplification bias [27] |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., DMSO) | Prevents ice crystal formation during cell freezing | Essential for preserving cell viability in long-term storage [30] |

Protocol 1: Cell Preparation for Sensitive Rare Cell Detection

Proper cell preparation is paramount for the success of any downstream single-cell assay, especially when dealing with rare and potentially sensitive populations.

- Tissue Dissociation: For solid tissues, use a combination of mechanical and enzymatic dissociation. To minimize transcriptional changes, consider using cold-active proteases (e.g., from Bacillus licheniformis) and perform digestion at lower temperatures where possible [25].

- Cell Suspension and Viability: Resuspend cells in a physiological buffer (e.g., PBS without calcium and magnesium). Supplement with 0.1-1% BSA or 1-10% FBS to reduce non-specific binding and maintain viability. For tissues, cell viability >70% is considered adequate; for low viability samples, remove dead cells prior to analysis [30] [25].

- Prevention of Aggregation: Add DNAse I (e.g., 100 U/mL) to the suspension to digest free DNA released from dead cells, which is a primary cause of cell clumping [30].

- Cell Isolation: Use FACS or a microfluidic platform (e.g., 10x Genomics) to isolate single cells. When using FACS, employ singlet gates to exclude doublets and a "dump" channel to exclude unwanted cell types and dead cells. For very rare populations (<150,000 cells), limit cleanup steps to avoid excessive cell loss [30] [25].

- Cryopreservation (Optional): If cells cannot be processed immediately, cryopreserve them at a high concentration (e.g., 1 million cells/mL) in freezing medium containing a cryoprotectant like 10% DMSO. Frozen cells can be stored long-term in liquid nitrogen and have been shown to yield scRNA-seq profiles similar to fresh cells [30] [25].

Protocol 2: Computational Identification of Rare Cells using scSID

- Input Data Preparation:

- Obtain a cell-by-gene count matrix from a scRNA-seq processing pipeline (e.g., Cell Ranger for 10x Genomics data).

- Perform standard quality control: filter out cells with low unique gene counts or high mitochondrial gene percentage, which indicate low-quality or dying cells.

- Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction:

- K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) Graph Construction:

- Calculate the Euclidean distance between every pair of cells in the PCA-reduced space.

- For each cell, identify its K nearest neighbors. The default K is 100 for datasets with ~5000 cells or fewer. For larger datasets, K is generally set to no more than 2% of the total number of cells [24].

- Rare Cell Identification with scSID:

- For each cell, calculate the first-order difference of the distances to its KNNs to characterize the change in similarity.

- The scSID algorithm will then group cells with minimal characteristic differences and perform stepwise clustering synthesis to output the final set of identified rare cell populations [24].

The discovery of rare cell types is essential for advancing our understanding of complex biological systems, from developmental biology to disease pathogenesis. The algorithms discussed—scSID, CellSIUS, and Rarity—provide powerful and complementary tools for this task. scSID offers a fast, similarity-based approach with exceptional scalability for large datasets. CellSIUS provides high-specificity detection of rare subtypes and their functional transcriptomic signatures within pre-clustered major populations. Rarity brings a novel, interpretable Bayesian framework with high sensitivity to subtle expression differences. The choice of tool depends on the specific experimental context, the nature of the rare population, and the computational constraints. By following robust experimental and computational protocols, researchers can reliably uncover these elusive but critical cellular players, thereby deepening the insights gained from single-cell genomics.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the characterization of individual cells, uncovering vast cellular heterogeneity within tissues that was previously obscured by bulk analysis [31] [32]. This heterogeneity is a fundamental hallmark of complex tissues and diseases, particularly in cancer, where it contributes significantly to drug resistance and therapeutic failure [33]. The ability to resolve rare cell subpopulations—such as cancer stem cells, rare immune cell subtypes, or unique cellular states in development—is crucial for advancing our understanding of disease pathogenesis and identifying novel therapeutic targets [31] [34].

However, the very high-dimensionality, significant technical noise, and prevalent dropout events (where expressed genes fail to be detected) characteristic of scRNA-seq data pose substantial challenges for clustering algorithms, which are essential for identifying distinct cell types and states [31]. Traditional clustering methods often treat all cells uniformly and require pre-specification of the number of clusters, which is frequently unknown for complex or poorly characterized tissues [31]. This limitation is particularly problematic for rare cell type identification, as these populations can be easily overlooked or merged with more abundant types. To address these challenges, we have developed a novel two-step clustering approach, TSC (Two-Step Clustering), which strategically combines coarse-grained and fine-grained resolutions to enhance clustering accuracy and reliability, especially for detecting rare cell populations in scRNA-seq data [31].

Core Methodology and Experimental Protocols

The TSC Clustering Workflow

The TSC method operates on the principle that not all cells contribute equally to the initial definition of cluster centers. It systematically distinguishes between core cells, which are tightly connected to their neighbors and likely reside near the true centers of underlying biological clusters, and non-core cells, which are more peripherally located in the transcriptional landscape [31]. A formal workflow of the TSC procedure is as follows:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Transformation

- Input: Raw scRNA-seq count matrix (cells × genes).

- Gene Filtering: Filter genes based on expression thresholds to remove noise.

- Log-Transformation Decision: Calculate the Right-Skewed Coefficient (RSC) of the data distribution. Apply Log-transformation if RSC indicates severe right-skewness to mitigate the impact of extreme outlier values [31].

- Output: Normalized and transformed expression matrix.

Step 2: Cell Graph Construction and Core Cell Identification

- Similarity Calculation: Compute cell-to-cell similarities using a chosen metric (e.g., Pearson Correlation Coefficient - PCC, Spearman Correlation Coefficient - SCC) [31].

- Graph Formation: Construct a k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) graph where nodes represent cells and edges connect cells within their mutual k-nearest neighbors.

- Core Cell Designation: Identify core cells as those with a high local connection density or a high number of connections within the k-NN graph. Non-core cells are those with sparser connections [31].

Step 3: Coarse-Grained Clustering of Core Cells

- Distance Calculation: Compute the Random Walk Distance on the cell graph for all pairs of core cells. This distance metric is more robust in capturing global manifold structure compared to direct Euclidean distance in high-dimensional space [31].

- Hierarchical Clustering: Perform hierarchical clustering (e.g., using Ward's method) on the core cells using the random walk distance matrix.

- Cluster Number Determination: Automatically determine the number of clusters, k, from the core cells using an internal validation criterion, eliminating the need for user pre-specification [31].

Step 4: Fine-Grained Assignment of Non-Core Cells

- Cluster Assignment: Assign each non-core cell to the nearest cluster (from Step 3) based on its distance to the core cells in that cluster. This can be done using a simple nearest-neighbor classifier or by calculating the median distance to the core members of each cluster [31].

- Output: Final cluster labels for all cells (both core and non-core).

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points of the TSC protocol:

Detailed Experimental Protocol for scRNA-seq Clustering

Objective: To identify distinct cell populations, including rare cell types, from a scRNA-seq dataset using the TSC method.

Materials and Reagents:

- Single-Cell Suspension: Viable single-cell suspension from tissue dissociations or cell culture.

- scRNA-seq Library Prep Kit: Commercial kit (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kit, SMART-Seq HT Kit).

- Sequencing Reagents: Appropriate next-generation sequencing flow cell and sequencing reagents (e.g., Illumina sequencing kits).

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster or workstation with sufficient RAM (>32 GB recommended).

- Software: R (v4.0+) or Python (v3.8+) environment with necessary packages.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Input:

- Obtain a gene expression matrix (cells × genes) from your scRNA-seq pipeline. Standard file formats include MTX (Matrix Market) or a plain text tab-delimited file.

- Load the data into your analytical environment (R/Python). The initial matrix should contain raw UMI counts or FPKM/TPM values, depending on the technology [31].

Preprocessing and Quality Control (QC):

- Cell QC: Filter out cells with a high percentage of mitochondrial reads (indicative of apoptosis or low quality) or an unusually low number of detected genes.

- Gene QC: Filter out genes that are detected in fewer than a specified number of cells (e.g., <10 cells).

- Normalization: Normalize the library sizes across cells. A common approach is to scale the total counts per cell to a standard value (e.g., 10,000), followed by log-transformation of the normalized counts [31].

Execute TSC Clustering:

- Implement the TSC algorithm as described in Section 2.1. The algorithm's steps can be coded in R or Python. Key parameters to consider:

- Similarity Metric: Choose from PCC, SCC, Euclidean Distance, etc. Based on benchmark studies, PCC or SCC is recommended for optimal performance [31].

- k for k-NN Graph: The number of nearest neighbors for graph construction. A starting value of

k = min(100, round(0.5% * total_cells))is often effective.

- The output is a cluster label for every cell in the dataset.

- Implement the TSC algorithm as described in Section 2.1. The algorithm's steps can be coded in R or Python. Key parameters to consider:

Post-Clustering Analysis:

- Visualization: Project the clustering results onto a 2D visualization such as t-SNE or UMAP to visually assess cluster separation.

- Differential Expression (DE): Perform DE analysis between clusters (e.g., using Wilcoxon rank-sum test) to identify marker genes for each cluster. These markers are crucial for annotating the biological identity of the clusters, including the putative rare cell type.

- Rare Population Validation: For the small cluster(s) of interest (potential rare cells), validate their identity using known marker genes from the literature and/or through independent experimental validation (e.g., fluorescence in situ hybridization).

Performance and Validation

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The TSC method was rigorously evaluated against state-of-the-art clustering methods on 12 publicly available real scRNA-seq datasets [31]. These datasets varied in size, number of cell types, and sequencing protocols. Clustering performance was measured using the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), which quantifies the similarity between the clustering result and the ground truth cell type labels (where 1 indicates perfect match) [31]. The choice of similarity metric within TSC was found to be critical for its performance.

Table 1: Performance of TSC with Different Similarity/Distance Metrics Across 12 Real scRNA-seq Datasets (ARI Values) [31]

| Dataset | TSC_ED | TSC_MD | TSC_PCC | TSC_SCC | TSC_SNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE52529 | 0.751 | 0.743 | 0.812 | 0.832 | 0.724 |

| GSE67835 | 0.681 | 0.669 | 0.745 | 0.779 | 0.652 |

| GSE71585 | 0.723 | 0.710 | 0.798 | 0.815 | 0.701 |

| GSE75748 | 0.665 | 0.658 | 0.731 | 0.752 | 0.640 |

| GSE82187 | 0.812 | 0.799 | 0.884 | 0.871 | 0.781 |

| GSE83139 | 0.778 | 0.765 | 0.859 | 0.841 | 0.752 |

| GSE84133 | 0.801 | 0.792 | 0.867 | 0.850 | 0.774 |

| GSE94820 | 0.745 | 0.733 | 0.826 | 0.809 | 0.718 |

| GSE103239 | 0.769 | 0.761 | 0.843 | 0.828 | 0.743 |

| GSE109774 | 0.794 | 0.785 | 0.861 | 0.845 | 0.769 |

| GSE119651 | 0.815 | 0.806 | 0.878 | 0.862 | 0.790 |

| GSE132042 | 0.832 | 0.821 | 0.892 | 0.875 | 0.805 |

| Average ARI | 0.763 | 0.753 | 0.833 | 0.821 | 0.738 |

The results demonstrate that TSCPCC (using Pearson Correlation Coefficient) and TSCSCC (using Spearman Correlation Coefficient) consistently outperformed other metrics, achieving the highest average ARI scores [31]. This highlights the superiority of correlation-based measures over traditional distance metrics like Euclidean Distance (ED) or Manhattan Distance (MD) for capturing biological similarity in scRNA-seq data. Overall, TSC was shown to outperform several existing state-of-the-art methods in clustering accuracy across these diverse benchmarks [31].

Advantages of the Two-Step Strategy for Rare Cell Identification

The two-step coarse-to-fine strategy provides distinct advantages for rare cell type detection:

- Robust Cluster Center Formation: By initially clustering only the tightly connected core cells, TSC reduces the "pull" exerted by outlier or boundary cells (non-core cells) on the definition of cluster centroids. This leads to more stable and biologically meaningful cluster definitions from the outset [31].

- Enhanced Rare Population Discovery: Small, distinct groups of rare cells are more likely to be identified as separate core clusters if their transcriptional profiles are cohesive, rather than being absorbed into larger, more diffuse clusters as can happen in one-step global clustering methods.

- Automatic Cluster Number Determination: TSC's ability to automatically determine the number of clusters from the data is a significant practical advantage, as the number of distinct cell types (including rare types) in a sample is often unknown a priori [31].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The precise identification of cell subtypes via advanced clustering methods like TSC integrates deeply into the modern drug discovery and development pipeline. The following diagram illustrates key application areas:

Table 2: Key Applications of Single-Cell Clustering in Drug Discovery and Development [33] [35] [34]

| Application Area | Description | Impact of TSC Clustering |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification & Prioritization | Identifying novel therapeutic targets by discovering disease-associated cell subpopulations and their specific gene expression signatures [35] [34]. | Reveals subtle but biologically critical rare cell populations (e.g., drug-resistant precursors, rare immune effectors) that harbor potential new targets. |

| Mechanism of Action (MoA) Elucidation | Profiling gene expression changes in cells treated with drug candidates to understand affected pathways and biological processes [35]. | Clarifies if a drug's effect is specific to a rare subpopulation, distinguishing it from bulk effects and providing a more precise MoA. |

| Biomarker Discovery & Patient Stratification | Identifying cell-specific molecular signatures associated with treatment response or disease progression for developing companion diagnostics [35] [34]. | Enables the discovery of rare cell-type-specific biomarkers that are more predictive of clinical outcome than bulk tissue biomarkers. |

| Understanding Drug Resistance | Characterizing the cellular heterogeneity of tumors to identify pre-existing or acquired rare cell subpopulations that drive resistance [33]. | Directly identifies and characterizes rare, resistant subclones within a heterogeneous tumor, which is essential for developing combination therapies. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq and Clustering Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Generates sequencing libraries from single-cell suspensions. | 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell Gene Expression Solution; SMART-Seq HT Kit [31] [32]. Choose based on required cell throughput and gene capture sensitivity. |

| Viability Stain | Distinguish live cells for viable cell sorting prior to library prep. | Propidium Iodide (PI); DAPI; Fluorescent dyes for flow cytometry. |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Lyse cells within droplets or wells to release RNA for capture. | Typically provided with the library prep kit. Contains detergents and RNase inhibitors. |

| mRNA Capture Beads | Oligo-dT coated beads that capture poly-adenylated mRNA and introduce cell barcodes and UMIs. | Barcoded magnetic beads (e.g., from 10x Genomics) [32]. Crucial for multiplexing thousands of single cells. |

| Reverse Transcriptase (RT) Reagents | Perform reverse transcription on the bead-bound mRNA to synthesize barcoded cDNA. | Enzymes and nucleotides provided in the kit. |

| PCR Amplification Reagents | Amplify the cDNA library to generate sufficient material for sequencing. | High-fidelity PCR mix. Cycle number must be optimized to avoid amplification bias. |

| Sequencing Reagents | For high-throughput sequencing of the final libraries on the appropriate platform. | Illumina sequencing kits (e.g., MiSeq, NovaSeq). |

| Bioinformatics Software/Packages | Perform read alignment, gene counting, quality control, and downstream clustering analysis (like TSC). | Cell Ranger (10x Genomics), Seurat (R), Scanpy (Python). |

Concluding Remarks

The TSC strategy, which strategically separates coarse-grained clustering of core cells from the fine-grained assignment of non-core cells, provides a robust and effective framework for scRNA-seq data analysis. Its demonstrated superiority over existing methods, coupled with its ability to automatically determine the number of clusters, makes it a powerful tool for deconvoluting cellular heterogeneity [31]. This is particularly impactful in the context of drug discovery and development, where the precise identification of rare cell types—such as those driving disease pathogenesis, mediating drug resistance, or representing novel therapeutic targets—can significantly reshape research trajectories and improve clinical outcomes [33] [35] [34]. By integrating this advanced computational approach with established experimental protocols, researchers can gain a deeper, more accurate understanding of complex biological systems at single-cell resolution.

Within the framework of single-cell analysis for rare cell type identification, the limitations of relying solely on transcriptomic data have become increasingly apparent. Gene expression data alone can be insufficient for confidently distinguishing closely related cell states or identifying rare cell populations with high certainty [36]. The integration of multi-modal data types, such as cell surface protein expression from CITE-seq and spatially resolved transcriptional information from spatial transcriptomics, provides a powerful strategy to overcome these limitations. By combining independent lines of evidence, researchers can achieve a more comprehensive cellular characterization, leading to higher confidence in cell type annotation—a critical requirement for meaningful biological discovery and therapeutic development [37] [36] [38].