Validating Hot-Spot Residues by Alanine Scanning: A Guide for Drug Discovery Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of hot-spot residues through alanine scanning mutagenesis.

Validating Hot-Spot Residues by Alanine Scanning: A Guide for Drug Discovery Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of hot-spot residues through alanine scanning mutagenesis. We cover the foundational principles of protein-protein interactions and hot spots, detail state-of-the-art methodological approaches from experimental to high-throughput computational techniques, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present a framework for rigorous validation through comparative analysis with other biophysical methods. The integration of these strategies is crucial for accurately identifying key residues that drive binding affinity, thereby informing the rational design of targeted therapeutics.

Protein-Protein Interactions and Hot Spots: The Energetic Foundation of Binding

In protein-protein interactions (PPIs), hot spots are defined as residues that contribute significantly to the binding free energy. Experimental identification via alanine scanning mutagenesis is the gold standard, but it is costly and time-consuming. This has spurred the development of diverse computational methods to predict these critical residues. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance, methodologies, and applicability of major computational hot spot prediction tools, contextualized within experimental validation frameworks crucial for researchers and drug development professionals.

Most cellular processes are governed by protein-protein interactions, and understanding their precise mechanisms is vital for drug discovery. Within the large surface of a protein-protein interface, the binding energy is not distributed uniformly. Instead, a small subset of residues, known as hot spots, accounts for the majority of the binding free energy [1] [2].

The canonical experimental method for identifying hot spots is alanine scanning mutagenesis. This technique involves systematically mutating individual interface residues to alanine and measuring the resulting change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) [1] [3]. A residue is typically defined as a hot spot if its mutation to alanine causes a ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol [1] [4]. This experimental definition, established by Clackson and Wells, forms the basis for validating computational predictions [1].

Despite its reliability, experimental alanine scanning is low-throughput. Each mutant must be expressed, purified, and analyzed separately, making it prohibitively expensive and slow for large-scale studies [1] [3]. Consequently, computational methods have been developed to predict hot spots from protein structure and sequence data, offering a rapid and scalable alternative.

Computational hot spot prediction methods can be broadly categorized into several types based on their underlying algorithms. The table below summarizes the key features of prominent methods.

Table 1: Overview of Major Computational Hot Spot Prediction Methods

| Method Name | Category | Required Input | Key Features/Algorithm | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX [1] [3] | Energy-Based / Empirical Force Field | Protein Complex Structure | Computational alanine scanning using an empirical force field. | Standalone Tool & Server |

| Robetta [1] [3] | Energy-Based / Physical Force Field | Protein Complex Structure | Computational alanine scanning using the Rosetta force field and conformational sampling. | Server |

| MM/GBSA/IE [5] | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation | Protein Complex Structure | Binds free energy calculation from MD trajectories using Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area with Interaction Entropy. | Research Code |

| BudeAlaScan [3] | Energy-Based / Empirical Force Field | Protein Complex Structure or Ensemble | Adapted from a small-molecule docking algorithm (BUDE); can process structural ensembles from NMR or MD. | Command-Line Tool |

| HotSprint [6] | Knowledge-Based / Conservation | Protein Complex Structure | Combines evolutionary conservation from Rate4Site and solvent accessibility (ASA). | Database & Web Server |

| PredHS2 [7] | Machine Learning | Protein Complex Structure | Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model with 26 optimal features including novel solvent exposure and disorder scores. | Research Code |

| PPI-hotspotID [8] | Machine Learning | Free Protein Structure | Ensemble classifier using only 4 residue features (conservation, aa type, SASA, and gas-phase energy). | Web Server |

| Min-SDS [4] | Graph Theory | Protein Complex Structure | Finds high-density subgraphs in residue interaction networks to identify potential hot spot clusters. | Research Code |

Performance Comparison of Prediction Tools

The predictive performance of these tools is typically benchmarked against experimental data from databases like ASEdb, BID, and SKEMPI. The following table summarizes quantitative performance metrics from independent studies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Select Prediction Methods

| Method | Reported Accuracy | Reported Sensitivity/Recall | Reported Precision | Reported F1-Score | Test Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HotSprint [6] | 76.8% | 60.1% | 63.1% | 65.7% | ASEdb |

| PredHS2 [7] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.689 (10-fold CV) | Author's Dataset (313 residues) |

| PPI-hotspotID [8] | Not Specified | 0.67 | Not Specified | 0.71 | PPI-Hotspot+PDBBM (414 hot spots) |

| FTMap (PPI mode) [8] | Not Specified | 0.07 | Not Specified | 0.13 | PPI-Hotspot+PDBBM (414 hot spots) |

| Min-SDS [4] | Not Specified | 0.665 | Not Specified | F2-score: 0.364 | SKEMPI (67 complexes) |

| Mincut [4] | Not Specified | <0.400 | High (Best) | F2-score: <0.224 | SKEMPI (67 complexes) |

A comparative analysis of five computational alanine scanning (CAS) methods (FoldX, mCSM, BeAtMuSiC, Rosetta Flex_ddG, and BudeAlaScan) on the SKEMPI database revealed that while individual methods showed variable Pearson correlation coefficients with experimental ΔΔG, averaging the predictions from all five methods led to more accurate identification of hot spots than any single method alone [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

Experimental Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis

This protocol is the foundational experimental method for hot spot validation [1] [3].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Create a series of plasmid constructs, each encoding a variant of the protein of interest where a single interfacial residue is mutated to alanine.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and each alanine mutant protein using standard systems (e.g., E. coli, mammalian cell culture).

- Binding Affinity Measurement: Determine the binding affinity (often reported as the dissociation constant, Kd) of each protein variant for its binding partner using a technique such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), or similar.

- Energy Calculation: Calculate the change in binding free energy using the formula: ΔΔG = ΔGmut - ΔGwt = RT ln(Kdmut / Kdwt), where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature.

- Classification: A residue is classified as a hot spot if ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol.

Computational Alanine Scanning (CAS) with MM/GBSA

This MD-based protocol offers a quantitative theoretical approach [5].

- System Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein complex from the PDB. Add hydrogen atoms, solvate the complex in a water box, and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform energy minimization and equilibration, followed by a production MD run to generate a stable trajectory of the complex.

- Trajectory Generation for Mutants: Using the "single-trajectory approach," generate alanine mutant trajectories by computationally truncating the side chain of the target residue to alanine in each frame of the wild-type trajectory.

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Use the MM/GBSA method on both wild-type and mutant trajectories to calculate the binding free energy. The difference, ΔΔG, is computed for each residue.

- Hot Spot Prediction: Residues with a predicted ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol are identified as computational hot spots.

Machine Learning-Based Prediction with PredHS2

This protocol outlines a modern machine-learning workflow [7].

- Dataset Curation: Compile a training dataset of known hot spots and non-hot spots from databases like ASEdb, BID, and SKEMPI.

- Feature Extraction: For each residue, compute a wide array of ~600 features, including:

- Sequence features: Amino acid type, evolutionary conservation.

- Structural features: Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), secondary structure, atom packing density.

- Energetic features: Estimated energy terms.

- Neighborhood properties: Features from spatially adjacent residues (Euclidean and Voronoi neighborhoods).

- Feature Selection: Employ a two-step feature selection (e.g., mRMR and sequential forward selection) to identify an optimal, non-redundant feature set (e.g., 26 features for PredHS2).

- Model Training and Validation: Train a classifier (e.g., XGBoost for PredHS2) using the selected features and validate its performance via cross-validation and on independent test sets.

Successful hot spot analysis relies on a combination of experimental reagents and computational databases.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hot Spot Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Enables creation of alanine point mutations in plasmid DNA for protein expression. | Commercial kits from Agilent, NEB, etc. |

| Protein Expression System | Produces the wild-type and mutant proteins for binding assays. | E. coli, insect cell (baculovirus), or mammalian cell systems. |

| Binding Affinity Instrument | Measures the strength of protein-protein binding for wild-type and mutants. | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for 3D structural data of proteins and complexes, essential for computational methods. | https://www.rcsb.org/ [5] |

| SKEMPI Database | A curated database of binding free energy changes upon mutation, used for training and testing predictors. | SKEMPI 2.0 [3] [4] |

| ASEdb / BID | Legacy databases collecting experimental hot spot data from alanine scanning mutagenesis. | Alanine Scanning Energetics Database, Binding Interface Database [1] [6] |

The accurate prediction of hot spot residues is a critical step in understanding PPIs and for designing therapeutic agents that modulate these interactions. While experimental alanine scanning remains the validation gold standard, computational methods provide powerful and complementary high-throughput tools.

Energy-based methods like FoldX and MD-based MM/GBSA offer direct, physics-based interpretations but can be computationally demanding. Machine learning methods like PredHS2 and PPI-hotspotID often achieve high accuracy by integrating diverse features and are efficient for large-scale screening. Emerging graph theory approaches like Min-SDS show great promise in achieving high recall, identifying potential hot spots that other methods might miss.

For the most reliable results, a consensus approach—averaging predictions from multiple methods or using machine learning models that integrate various data types—is recommended. The choice of tool ultimately depends on the available input data (e.g., complex structure vs. free structure), required throughput, and the specific balance of precision and recall needed for the research objective.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to virtually all biological processes, from cell signaling to immune response [1] [3] [9]. The thermodynamic driving force for these interactions is not distributed uniformly across the large binding interfaces. Instead, it is frequently dominated by a small subset of residues known as "hot spots" [3]. These are residues that, when mutated to alanine, cause a significant reduction in binding free energy (typically ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [1]. Understanding the unique physicochemical properties of these hot spots is therefore crucial for deciphering the molecular logic of PPIs and for rational drug design aimed at modulating these interactions for therapeutic purposes [1] [10]. A consistent and striking finding from numerous experimental and computational studies is the marked prevalence of three aromatic and charged amino acids—tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine—within these functionally critical regions [1] [11] [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the roles of these amino acids in hot spot formation, supported by experimental data and the methodologies used to uncover them.

Quantitative Analysis of Amino Acid Prevalence in Hot Spots

Statistical analyses of known hot spot residues reveal a dramatically non-random distribution of amino acids. The enrichment of tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine is particularly remarkable when compared to other residue types.

Table 1: Amino Acid Prevalence in Protein-Protein Interaction Hot Spots

| Amino Acid | Prevalence in Hot Spots (%) | Key Physicochemical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan (W) | 21.0% | Large aromatic side chain, hydrophobic surface, π-interactions, indole nitrogen for H-bonding [1] [11] |

| Arginine (R) | 13.3% | Positively charged guanidinium group, forms multiple H-bonds and salt bridges, long flexible side chain [1] [11] |

| Tyrosine (Y) | 12.3% | Aromatic hydroxyl group, capable of both hydrophobic interactions and H-bonding, planar structure [1] [11] [12] |

| Other Residues | <10% each | |

| Leucine, Valine, Serine, Threonine, Methionine | <3% each | [11] |

This data, consolidated from multiple studies including the seminal work by Bogan and Thorn (1998), underscores that a few specific residues provide a disproportionate contribution to binding energy [11]. The functional implication is clear: the distinct physicochemical properties of Trp, Arg, and Tyr make them exceptionally suited for forming strong, specific interactions at protein interfaces.

Experimental Validation Through Alanine Scanning

The primary experimental protocol for identifying and validating hot spot residues is alanine scanning mutagenesis [1] [3]. This method provides the foundational data against which all computational predictions are benchmarked.

Core Protocol Workflow

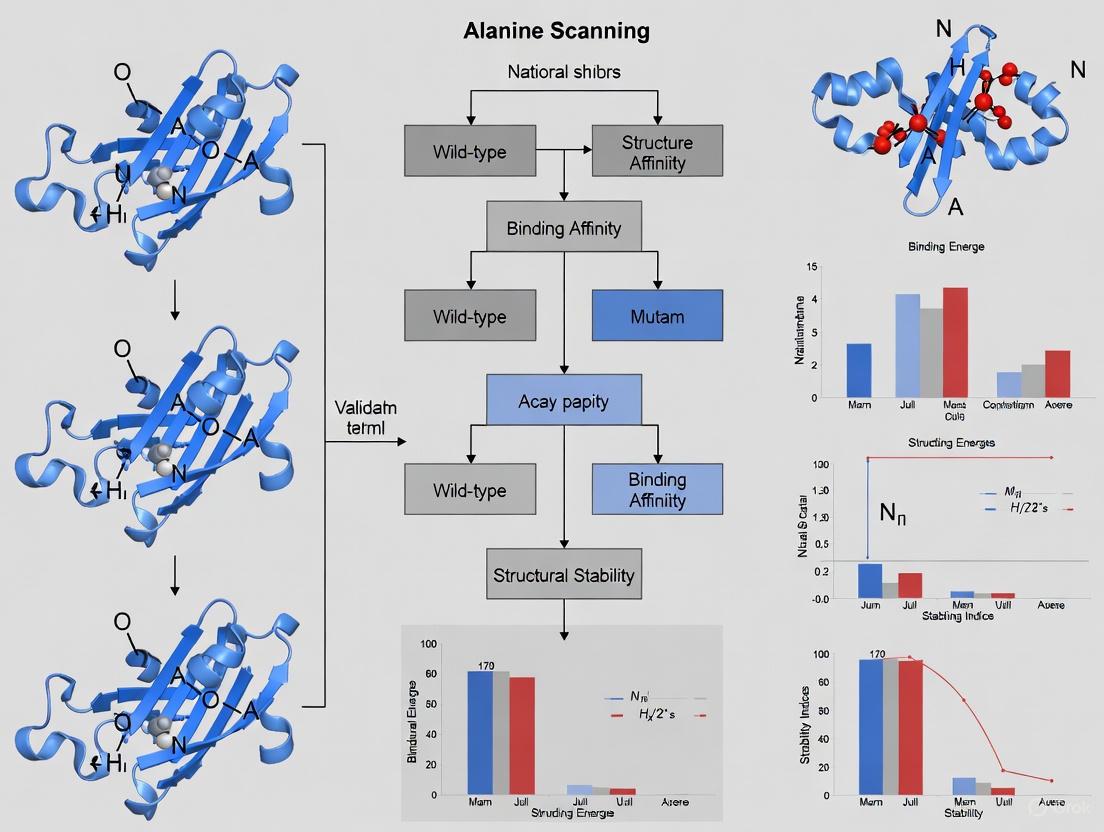

The following diagram outlines the standard workflow for experimental alanine scanning:

Methodology and Data Interpretation

The rationale for substituting residues with alanine lies in its inert methyl side chain, which removes all side-chain atoms beyond the β-carbon without introducing excessive conformational flexibility into the protein backbone, a problem associated with glycine mutations [1]. A measured binding free energy change (ΔΔG) of ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol upon mutation is the standard threshold for designating a residue as a hot spot, as this typically corresponds to a tenfold or greater decrease in binding affinity [1] [3].

The power of this protocol is illustrated by its application in seminal studies. For instance, alanine scanning of the human growth hormone (hGH) and its receptor identified key hot spot residues, two of which were tryptophans, establishing the very concept of hot spots [1]. Similarly, a study on insulin revealed TyrA19 as a critical hot spot, with an alanine mutation causing a 1,000-fold decrease in receptor binding affinity [13].

Table 2: Experimental Alanine Scanning Data for Selected Systems

| Protein Complex | Residue Mutated | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Classification | Citation/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Growth Hormone / Receptor | Tryptophan (W) | > 4.5 | Hot Spot | [1] |

| Insulin / Insulin Receptor | TyrA19 | ~4.1 (est. from 1000x loss) | Hot Spot | [13] |

| Insulin / Insulin Receptor | GlyB20 | ~ -0.6 (est. from increased affinity) | Non-Hot Spot (Affinity enhancing) | [13] |

| Model System | Any residue (e.g., Leu, Val, Ser) | < 2.0 | Non-Hot Spot | [11] |

Computational Prediction of Hot Spots

While accurate, experimental alanine scanning is time-consuming, expensive, and not scalable for proteome-wide studies [1] [3] [7]. This has driven the development of numerous computational methods for hot spot prediction, which can be broadly categorized into three groups.

Categories of Prediction Methods

- Energy-Based Methods: These tools use physical force fields or empirical scoring functions to calculate the difference in binding free energy upon alanine mutation. Examples include FoldX [1] [3], Robetta [1], and Rosetta Flex_ddG [3]. They effectively perform in silico alanine scanning.

- Machine Learning (ML) and AI-Based Methods: These approaches train classifiers on known hot spot data using a wide variety of features (sequence, structure, evolutionary conservation, etc.). Examples include KFC, HotPoint [3], PredHS2 [7], and mCSM [3]. Newer deep learning methods are also emerging [10].

- Hybrid and Novel Approaches: Newer methods like BudeAlaScan [3] and HotspotPred [9] combine empirical energy functions with the ability to analyze structural ensembles from NMR or MD simulations, or use structural templates to predict energetic contributions.

Performance Comparison of Computational Tools

Table 3: Comparison of Key Computational Hot Spot Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Methodology Category | Key Inputs | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Energy-Based | Protein Structure | Fast, user-friendly [3] | Accuracy can be variable; less accurate than some modern tools [3] |

| Rosetta Flex_ddG | Energy-Based | Protein Structure | High accuracy, sophisticated sampling [3] | Computationally intensive (hours per mutation) [3] |

| BudeAlaScan | Energy-Based | Protein Structure or Ensembles (NMR, MD) | Fast, can process multiple mutations and ensembles [3] | Newer method, command-line interface [3] |

| PredHS2 | Machine Learning | Protein Structure & Sequence | High accuracy, uses novel features (solvent exposure, disorder) [7] | Performance depends on training data quality [7] |

| mCSM/BeAtMuSiC | Machine Learning / Statistical | Protein Structure | Uses statistical potentials and machine learning [3] | Trained on specific databases (e.g., SKEMPI) [3] |

Studies have shown that combining predictions from multiple methods (consensus approaches) often yields more accurate and reliable identification of hot spots than relying on a single tool [3].

Advancing research in this field relies on a suite of key reagents, databases, and software tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hot Spot Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Hot Spot Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| SKEMPI Database | Database | Curated database of binding free energy changes for protein mutations [3] | Essential benchmark dataset for training and validating computational prediction tools [3] |

| ASEdb / BID | Database | Databases of experimental hot spots from alanine scanning mutagenesis [1] [7] | Provide ground-truth experimental data for analysis and method development [1] |

| Phage/Yeast Display | Experimental Platform | In vitro selection of high-affinity binding proteins [12] | Used to engineer synthetic binding proteins (e.g., nanobodies) that often target hot spots [9] [12] |

| QresFEP-2 | Computational Protocol | Hybrid-topology Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) simulation [14] | Physics-based method for predicting mutational effects on stability and binding with high accuracy [14] |

| Stable Protein Complexes | Experimental Reagent | Purified protein pairs for in vitro assays | Required for experimental binding affinity measurements (SPR, ITC) after mutagenesis. |

The empirical and computational data consistently affirm that tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine are the quintessential components of protein-protein interaction hot spots. Their unique physicochemical properties—large hydrophobic surfaces, capabilities for π-interactions, and versatile hydrogen bonding—make them uniquely suited to form high-affinity interaction nodes. The validation of these principles rests on the foundation of alanine scanning mutagenesis, a protocol that has definitively linked atomic-level composition to binding energy. While experimental methods remain the gold standard, the growing suite of computational tools provides powerful and scalable alternatives for hot spot prediction. The integration of these experimental and computational approaches, guided by a deep understanding of the special roles of Trp, Arg, and Tyr, continues to drive progress in structural biology and the rational design of therapeutics aimed at modulating the human interactome.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to most biological processes, and their dysregulation is a cornerstone of many diseases. While PPI interfaces can be large, it has been established that their binding energy is not distributed uniformly. Instead, a small subset of residues, known as "hot spots," contributes the majority of the binding free energy. This article explores the critical role of hot spots, their validation through alanine scanning, and their growing implications for drug discovery, providing a comparative guide to the methods used to identify these pivotal regions.

What Are Hot Spot Residues?

In the context of PPIs, a hot spot is typically defined as a residue whose mutation to alanine causes a significant decrease in binding free energy (ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [1]. These residues are not randomly distributed; they are often clustered and structurally conserved within the protein interface [1]. Their composition is also distinctive, with tryptophan (W), arginine (R), and tyrosine (Y) being the most frequently occurring hot spot residues [1].

The seminal work that identified hot spots involved the study of human growth hormone binding to its receptor, revealing that only a small fraction of the interface residues were energetically critical for the interaction [1]. This discovery underscored that PPI interfaces are not monolithic; they contain specific, targetable regions of high functional importance.

The O-Ring Theory and Hot Regions

A key model for understanding hot spot function is the "O-Ring" theory. It proposes that hot spot residues are often surrounded by a ring of less critical residues that shield them from solvent water, thereby protecting the high-energy interactions [15]. Furthermore, hot spots tend not to act in isolation but are organized into densely packed modules called "hot regions," which are critical for binding affinity and specificity [15].

Experimental Validation: Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis

The gold standard for experimental identification of hot spot residues is alanine scanning mutagenesis [1] [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: A residue of interest within the PPI interface is mutated to alanine using molecular biology techniques. Alanine is chosen because it removes all side-chain atoms past the β-carbon without introducing excessive flexibility or conformational strain to the protein backbone [1].

- Protein Expression and Purification: The wild-type and each alanine mutant protein are expressed in a suitable system (e.g., E. coli or mammalian cells) and subsequently purified [1].

- Binding Affinity Measurement: The binding constant of the mutant protein complex is measured and compared to that of the wild-type complex. Techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) can be used to determine the binding affinity.

- Energy Calculation: The change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) is calculated as ΔGmut – ΔGwt. A residue is designated a hot spot if the ΔΔG is ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol, which typically corresponds to at least a tenfold drop in binding affinity [1] [15].

Workflow of Alanine Scanning

The diagram below illustrates the multi-step process of experimentally validating a hot spot residue through alanine scanning.

Challenges of Experimental Methods

While highly informative, experimental alanine scanning is costly, time-consuming, and low-throughput [1] [16]. Each mutant must be individually constructed, expressed, purified, and analyzed, making it impractical for large-scale studies. Data from these experiments are deposited in databases like the Alanine Scanning Energetics Database (ASEdb) and the Binding Interface Database (BID), but the available information remains limited to a relatively small number of complexes [1].

Computational Prediction of Hot Spots

To overcome the limitations of experimental methods, a variety of computational tools have been developed. These can be broadly categorized into methods that require the bound complex structure and those that can work with a single unbound protein structure or even just the protein sequence.

The following table summarizes the properties and performance of several key computational methods.

| Method Name | Input Requirement | Core Methodology | Reported Performance (F1-Score/Other) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-hotspotID [16] [8] | Free Protein Structure | Machine Learning (Ensemble Classifier) | F1: 0.71 (on largest benchmark to date) | Uses conservation, aa type, SASA, and gas-phase energy. Integrated with AlphaFold-Multimer. |

| Embed-1dCNN [17] | Protein Sequence | Pre-trained protein embedding + 1D CNN | F1: 0.82 (on its test set) | Avoids manual feature engineering; uses deep learning on sequence data. |

| FTMap (PPI Mode) [18] [16] | Free Protein Structure | Computational solvent mapping / probe docking | Low Recall (0.07) vs. PPI-hotspotID [8] | Identifies consensus sites for small molecule fragment binding. |

| SPOTONE [8] | Protein Sequence | Machine Learning (Extremely Randomized Trees) | F1: 0.17 (vs. 0.71 for PPI-hotspotID) [8] | Predicts from sequence using residue-specific features. |

| FoldX [1] | Protein Structure (Bound) | Energy-based computational alanine scanning | N/A (Widely used energy function) | Empirical force field; calculates energy changes upon mutation. |

| Robetta [1] | Protein Structure (Bound) | Energy-based computational alanine scanning | N/A (Widely used server) | Uses a physical energy function and backbone flexibility. |

Performance Comparison of Prediction Methods

A 2024 study compared modern methods on the largest collection of experimentally confirmed hot spots to date (414 hot spots across 158 proteins) [16] [8]. The results clearly show the advancement of new machine-learning approaches:

- PPI-hotspotID significantly outperformed both FTMap and SPOTONE, achieving a much higher recall (0.67 vs. 0.07 and 0.10, respectively) and F1-score (0.71 vs. 0.13 and 0.17) [8].

- The study also found that combining PPI-hotspotID with interface residues predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer yielded better performance than either method alone [16].

The Critical Link: Hot Spots in Drug Discovery

Targeting PPIs with small-molecule drugs was once considered impossible because their interfaces are often large, flat, and lack deep pockets. The discovery of hot spots has fundamentally changed this perception [1] [15].

Why Hot Spots Are Druggable

Hot spots create localized regions of high energy density that are amenable to targeting. Key principles include:

- Energetic Contribution: A small molecule that effectively displaces a hot spot residue can disrupt the entire PPI by eliminating a major source of binding energy [1].

- Structural Pre-organization: Hot spots often exist in somewhat pre-organized states in the unbound protein, making them more accessible and "druggable" [15].

- Ligand Binding "Hot Spots": There is a strong correlation between residues identified as hot spots by alanine scanning and regions on the protein surface that have a high propensity to bind small molecule fragments (identified by methods like FTMap or SAR by NMR) [18] [19]. This overlap provides a strategic starting point for drug design.

From Hot Spot Prediction to Drug Discovery

The following diagram outlines how hot spot identification integrates into the drug discovery pipeline.

This approach has proven to be a valid strategy for disrupting unwanted PPIs, and several potential drugs targeting hot spots show great promise [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and computational tools essential for hot spot research.

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Hot Spot Research |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis Kits | Experimental Reagent | Streamline the process of creating site-directed alanine mutations for functional testing. |

| Sensitivity Labeled Nucleotides | Experimental Reagent | Used in sequencing to verify the correctness of introduced mutations. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Instrumentation / Assay | Gold-standard method for directly measuring binding affinity (Kd) and thermodynamics (ΔG) of wild-type vs. mutant complexes. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Instrumentation / Assay | Label-free technique for measuring binding kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity. |

| Fragment Libraries | Chemical Reagent | Collections of small, simple molecules used in X-ray crystallography or NMR to experimentally map protein surface hot spots. |

| PPI-hotspotID Web Server | Computational Tool | Predicts hot spot residues from the free protein structure using a machine-learning model [16]. |

| FTMap Server | Computational Tool | Computationally maps protein surfaces to identify regions with high propensity for binding small molecules [18]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Computational Tool | Predicts the structure of a protein complex, which can be used to identify interface residues for subsequent hot spot analysis [16]. |

Hot spot residues are central to understanding and modulating protein-protein interactions. The rigorous validation of these residues through alanine scanning provides the foundational evidence of their energetic importance. While experimental methods remain the benchmark, advanced computational tools like PPI-hotspotID and Embed-1dCNN are now achieving high predictive performance, enabling large-scale analysis.

The convergence of two definitions of "hot spots"—energetic contributions from alanine scanning and small molecule fragment binding propensity—has created a powerful paradigm for drug discovery. By focusing therapeutic design efforts on these critical regions, researchers can develop targeted strategies to disrupt pathological PPIs, turning a fundamental biological insight into tangible clinical potential.

In the field of molecular biology and drug discovery, understanding the precise interactions that govern protein-protein and protein-ligand binding is paramount. Among the techniques available to researchers, the alanine scanning experiment has established itself as the gold standard for thermodynamic measurement of functional residues in protein interfaces. This methodology systematically quantifies the contribution of individual amino acid side chains to binding free energy through point mutation to alanine, providing a robust experimental approach for identifying "hot spots"—critical residues that account for the majority of binding energy in molecular interactions [1] [20]. The technique's preeminence stems from its elegant simplicity and profound thermodynamic basis: by replacing a side chain with alanine's inert methyl group, researchers can precisely determine the energetic consequences of removing specific chemical functionalities while minimizing structural perturbations [1] [20]. This review objectively compares alanine scanning with emerging computational alternatives, providing researchers with a comprehensive analysis of methodological performance in the critical context of hot-spot validation for drug development.

Fundamental Principles and Thermodynamic Basis

Core Mechanism and Energetic Interpretation

Alanine scanning operates on a fundamental thermodynamic principle: the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) resulting from substituting a specific residue with alanine directly quantifies that residue's contribution to molecular recognition and binding. The experiment measures the discrepancy between the wild-type and mutant binding free energies (ΔGwt and ΔGmut), where ΔΔGbinding = ΔGmut – ΔGwt [1]. A residue is formally classified as a "hot spot" when its mutation to alanine causes a significant decrease in binding affinity, typically quantified as ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol [1]. This threshold identifies residues that contribute substantially to complex formation, with tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine statistically overrepresented at these critical positions [1].

The choice of alanine as the substitution standard is deliberate and scientifically grounded. Alanine possesses a non-bulky, chemically inert methyl functional group that mimics the secondary structure preferences of many other amino acids without introducing extreme conformational flexibility or steric clashes [1] [20]. Notably, glycine is avoided despite its small size because its lack of a β-carbon can introduce unwanted backbone flexibility, potentially confounding results with structural artifacts rather than pure side-chain energetic contributions [1].

The Alanine-World Model and Structural Preservation

The theoretical foundation of alanine scanning is supported by the Alanine-World model, which predicts that most canonical amino acids can be exchanged with alanine while maintaining protein secondary structure integrity [20]. This preservation of structural framework is crucial for valid thermodynamic interpretation, as it ensures that measured energy differences primarily reflect the loss of specific side-chain interactions rather than global structural rearrangements. The model leverages alanine's unique ability to mimic the conformational preferences of diverse residue types, establishing it as an ideal neutral reference point for comparative thermodynamic analysis [20].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Experimental Workflow

The implementation of alanine scanning follows a systematic workflow that integrates molecular biology, protein engineering, and precise biophysical measurement. The following diagram illustrates the core experimental process:

Alanine Scanning Experimental Workflow

The process begins with site-directed mutagenesis of selected interface residues to alanine, creating a series of mutant proteins [20]. Each mutant undergoes recombinant expression and purification before precise measurement of binding affinity using biophysical techniques. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) provides direct measurement of thermodynamic parameters including binding constant (K~a~), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS), offering comprehensive insight into the energetic drivers of molecular recognition [21] [22]. Alternative methods include surface plasmon resonance (SPR) for kinetic analysis and biological activity assays measuring second messenger production (e.g., IP1 accumulation for GPCRs) [23].

Advanced Implementation with Calorimetric Detection

Sophisticated implementations combine alanine scanning with ITC for enhanced mechanistic insight. In studying the CD4/gp120 interaction critical to HIV-1 entry, researchers employed thermodynamic guided alanine scanning to distinguish between binding hotspots and allosteric hotspots [22]. This approach revealed that not all residues contributing to binding affinity trigger the conformational changes associated with signaling, enabling design of inhibitors that block interaction without initiating unwanted signaling events [22]. For each alanine mutant, structural integrity must be verified through methods like differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to ensure melting temperatures (T~m~) remain comparable to wild-type, confirming that observed effects stem from side-chain removal rather than global destabilization [22].

Performance Comparison: Experimental vs. Computational Methods

Direct Methodological Comparison

While alanine scanning provides experimental gold standard data, computational approaches offer complementary advantages in throughput and cost-efficiency. The table below summarizes the objective performance characteristics of major methodological categories:

| Method | Key Principle | Throughput | Cost | Accuracy/ Precision | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Alanine Scanning [1] [24] [21] | Direct measurement of ΔΔG via mutagenesis and biophysical measurement | Low to Moderate (individual mutants) | High (specialized equipment, reagents) | High (experimental precision) | Validation studies, drug optimization, fundamental mechanistic studies |

| Computational Alanine Scanning [1] [24] | In silico estimation of ΔΔG using molecular dynamics and energy functions | High (parallel processing) | Low (computational resources) | Moderate (correlation ~0.7-0.8 with experimental) [24] | Preliminary screening, large-scale interface analysis |

| Machine Learning Prediction [25] | Feature-based classification using trained models (e.g., SVM, random forests) | Very High (instant prediction) | Very Low | Variable (F1-score ~0.70 on benchmark sets) [25] | Proteome-wide analysis, initial target identification |

Empirical Accuracy Assessment

A comparative study examining the trypsin-synthetic peptide complex provides direct evidence of performance differences between methodological approaches. The research demonstrated that a 'post-process alanine scanning' computational protocol, which analyzes a single native complex trajectory, achieved better accuracy than running separate molecular dynamics simulations for individual mutants [24]. Notably, results from post-process alanine scanning were also more precise across 10 independent simulations and were obtained over five times faster than the full molecular dynamics protocol [24]. However, the same study reaffirmed that computational methods ultimately serve as approximations to experimental measurements, with even the most efficient algorithms requiring experimental validation for definitive hot spot identification.

Application Case Studies in Research and Development

Diverse Biological Systems Illustrate Methodological Versatility

Alanine scanning has delivered critical insights across diverse biological contexts, from neurotransmission to immunology. The following diagram illustrates the relationships between key application areas and their specific research outcomes:

Key Application Areas and Outcomes

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from these representative studies:

| Biological System | Key Residues Identified | Measured ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bombesin Receptor (GPCR) [23] | Tryptophan, Histidine | Not specified | Critical for receptor binding and activation; guided SERS/SEIRA studies |

| Ca~V~α1-Ca~V~β Interaction [21] | Four conserved hotspot residues | ~2.0-4.5 (significant decrease) | Essential for channel trafficking and functional modulation |

| TCR-pMHC Interaction [26] | CDR3β residues | Not specified (significant reduction) | Enabled engineering of higher avidity TCRs for immunotherapy |

| CD4/gp120 (HIV-1) [22] | Distinct binding vs. allosteric hotspots | Variable by mutant | Enabled design of non-activating competitive inhibitors |

| Aβ(1-40) Amyloid Fibrils [27] | Core hydrophobic residues | Not specified (increased critical concentration) | Revealed determinants of fibril stability and elongation |

Industrial Research and Therapeutic Development

In pharmaceutical development, alanine scanning has proven invaluable for optimizing therapeutic agents. For instance, in the development of HIV-1 cell entry inhibitors, thermodynamic guided alanine scanning identified that not all binding hotspots are allosteric hotspots, enabling rational design of inhibitors that block the CD4/gp120 interaction without triggering the conformational changes that lead to viral entry [22]. Similarly, in T cell receptor engineering for cancer immunotherapy, alanine scanning rapidly mapped key interacting residues in TCR CDR3 regions, facilitating the design of focused mutant libraries and selection of TCRs with higher binding avidity for improved tumor recognition [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of alanine scanning requires specialized reagents and instrumentation. The following table details core components of the experimental toolkit:

| Reagent/Instrument | Specification/Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Commercial kits (e.g., Agilent QuikChange) for introducing point mutations | Critical for creating alanine substitutions; requires sequence verification [22] |

| Expression Systems | Mammalian (e.g., HEK-293), bacterial, or yeast expression systems | Choice affects proper folding and post-translational modifications [23] [22] |

| Purification Systems | Affinity chromatography (His-tag, antibody), FPLC | Required for obtaining pure protein for biophysical studies [22] |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Direct measurement of binding thermodynamics (K~d~, ΔH, ΔS) | Gold standard for label-free binding measurements [21] [22] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Kinetic analysis of binding interactions (on/off rates) | Alternative to ITC when kinetics are of primary interest |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Assesses protein stability and folding integrity | Verifies mutations don't destabilize protein structure [22] |

Integrated Workflow for Hot-Spot Validation

The most effective contemporary research employs an integrated strategy that combines computational prediction with experimental validation. The optimal workflow begins with machine learning prediction (e.g., HEP, KFC2, or APIS methods) to prioritize target residues, followed by computational alanine scanning to refine predictions, and culminates in experimental alanine scanning for definitive validation [25]. This tiered approach maximizes efficiency while maintaining methodological rigor, with computational methods screening large interfaces and experimental verification providing thermodynamically precise data for critical residues.

Alanine scanning remains the unchallenged gold standard for experimental determination of residue-specific thermodynamic contributions to protein interactions. While computational methods continue to advance in predictive accuracy and throughput, their performance must still be evaluated against experimental alanine scanning data for validation [24] [25]. For research requiring definitive identification of functional hot spots—particularly in drug development contexts where precise energetic measurements inform optimization campaigns—experimental alanine scanning provides irreplaceable thermodynamic precision. The methodology's continued relevance is assured through integration with emerging structural techniques and computational approaches, maintaining its position as the definitive reference point for thermodynamic measurement of protein interaction interfaces.

From Bench to Code: Executing Experimental and Computational Alanine Scanning

Alanine scanning mutagenesis stands as a cornerstone experimental methodology for mapping protein-protein and protein-ligand interaction interfaces by systematically identifying "hot spot" residues that contribute significantly to binding energy. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of experimental approaches, detailing the complete workflow from library design and mutagenesis through binding affinity measurement and data interpretation. We objectively evaluate the protocol's performance against alternative methodologies and present quantitative experimental data validating its crucial role in characterizing energetic landscapes at biological interfaces.

The systematic identification of functional epitopes represents a fundamental challenge in understanding molecular recognition, with profound implications for therapeutic antibody development, drug discovery, and protein engineering. Within this context, alanine scanning mutagenesis has emerged as a powerful experimental paradigm for quantitatively mapping binding energy contributions at amino acid resolution [28]. The technique operates on a straightforward biochemical principle: by substituting individual residues with alanine—thereby removing side-chain atoms beyond the β-carbon—researchers can probe the energetic contribution of specific side chains to binding interactions [29].

The conceptual foundation of this approach rests on the "hot spot" hypothesis, which proposes that binding energy is not uniformly distributed across interaction interfaces but is instead concentrated at a relatively small subset of residues [28]. Experimental validation of these hot spots through alanine scanning has revealed that protein interfaces display remarkable diversity in their energetic organization, with no simple patterns of hydrophobicity, shape, or charge reliably predicting which residues will prove functionally critical [28]. This methodology has been successfully applied to diverse systems including antibody-antigen complexes [30], insulin-receptor interactions [13], and G-protein coupled receptor signaling [31], establishing it as an indispensable tool for dissecting the thermodynamic determinants of molecular recognition.

Experimental Workflow: From Mutagenesis to Binding Measurement

The implementation of a comprehensive alanine scanning study requires the execution of a multi-stage experimental pipeline, each component of which must be carefully optimized to ensure reliable results.

Stage 1: Target Selection and Mutagenesis Strategy

The initial phase involves strategic selection of residues for mutagenesis based on structural or homology data to define the interface region. As exemplified in studies of antibody variable domains, researchers first identify permissive sites in complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that can be mutated without complete loss of antigen binding [30]. This preliminary assessment may involve computational alanine scanning to prioritize residues for experimental investigation [3] [32]. The mutagenesis strategy must balance comprehensiveness against practical constraints, with typical studies examining 15-30 interface residues [13].

Stage 2: Mutant Generation and Protein Production

Following target selection, researcher employ site-directed mutagenesis to systematically substitute each selected residue with alanine. The canonical approach involves:

- Generating 21+ individual mutant constructs for comprehensive interface mapping [13]

- Expressing mutant proteins in suitable systems (typically bacterial or mammalian)

- Purifying variants using chromatography methods (e.g., metal-affinity chromatography)

- Verifying structural integrity through methods like SDS-PAGE analysis [30]

This phase represents one of the most resource-intensive aspects of the protocol, requiring production and purification of numerous individual protein variants [29].

Stage 3: Binding Affinity Measurement

With purified mutant proteins in hand, researchers quantitatively assess binding interactions using appropriate biophysical methods. Common approaches include:

- Fluorescence polarization to measure changes in binding affinity at multiple protein concentrations [30]

- Surface display technologies (yeast, phage) for higher-throughput screening [30]

- ELISA or Western blot assays as accessible alternatives for binding assessment [29]

Critical to this phase is measuring the change in free energy of binding (ΔΔG) relative to wild-type, calculated from changes in binding constants (Kd or Ki values) [13] [31].

Stage 4: Data Interpretation and Hot Spot Validation

The final stage involves classifying residues based on their energetic contributions, with hot spots typically defined as those where alanine substitution causes a ≥10-fold reduction in binding affinity (ΔΔG ≥ 1.36 kcal/mol) [28]. Researchers must exercise caution in interpretation, as mutations may indirectly affect binding through structural perturbations rather than direct involvement in the interface [28].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters in Alanine Scanning Studies

| Parameter | Typical Range | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Residues scanned | 15-30 positions | Focus on structural epitope; balance between comprehensiveness and practicality |

| Expression system | Bacterial (E. coli) or mammalian | Impacts folding, post-translational modifications |

| Binding assay | Fluorescence polarization, ELISA, surface display | Throughput, precision, and equipment requirements vary |

| ΔΔG threshold for hot spots | ≥1.36 kcal/mol (10-fold affinity loss) | Classification sensitivity/specificity trade-offs |

| Replicates | 2-3 independent experiments | Essential for statistical significance |

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow:

Quantitative Experimental Data: Representative Case Studies

Insulin Receptor Binding Interface

A comprehensive alanine scanning study of insulin revealed distinct energetic contributions across its receptor binding interface, with dramatic variations in mutational effects [13]. The data demonstrate how alanine scanning quantitatively identifies critical hot spots while also revealing potential affinity-enhancing mutations:

Table 2: Alanine Scanning Results for Insulin-Receptor Binding [13]

| Mutation Position | Fold Change in Affinity | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| TyrA19 | 1,000-fold decrease | ~4.1 | Hot spot |

| GlyB8 | 33-fold decrease | ~2.1 | Hot spot |

| LeuB11 | 14-fold decrease | ~1.6 | Hot spot |

| GluB13 | 8-fold decrease | ~1.2 | Significant |

| GlyB20 | Increase | ~ -0.6 | Affinity enhancer |

| ArgB22 | Increase | ~ -0.4 | Affinity enhancer |

| SerA9 | Increase | ~ -0.3 | Affinity enhancer |

This dataset illustrates several key principles: (1) hot spot residues can produce dramatically different energetic penalties (from 8-fold to 1,000-fold reductions), (2) even conserved residues may not always be critical for binding (GlyB20), and (3) some mutations can paradoxically enhance affinity, providing insights for protein engineering.

Antibody Affinity Maturation Applications

In antibody engineering, alanine scanning guides affinity maturation strategies by identifying permissive sites for mutagenesis. One study of a single-domain antibody (VHH) specific for α-synuclein combined computational and experimental alanine scanning to identify CDR positions tolerant to mutagenesis [30]. The research team first identified 11 permissive sites that retained >50% wild-type binding when mutated to alanine, then designed focused libraries that yielded variants with >5-fold affinity improvements. This demonstrates how alanine scanning serves as a critical preliminary step in rational library design for antibody optimization.

Comparative Method Assessment: Performance Versus Alternatives

Direct Comparison with HDX-MS Epitope Mapping

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) represents a leading alternative for epitope mapping that measures protection from exchange upon binding:

Table 3: Alanine Scanning vs. HDX-MS for Epitope Mapping [29]

| Parameter | Alanine Scanning | HDX-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Single amino acid | Peptide-level (1-5 amino acids) |

| Throughput | Low (weeks-months) | Medium (days-weeks) |

| Sample consumption | High (each mutant individually) | Low (single complex analysis) |

| Energetic information | Direct ΔΔG measurement | Indirect (protection correlates with binding) |

| Structural perturbations | Possible conformational effects | Minimal (native conditions) |

| Equipment requirements | Standard molecular biology | Specialized mass spectrometry |

| Data interpretation | Straightforward (binding measurements) | Complex (exchange kinetics analysis) |

Computational Alanine Scanning Methods

Computational approaches provide complementary strategies for hot spot prediction with distinct performance characteristics:

Table 4: Computational Alanine Scanning Method Comparison [3]

| Method | Approach | Accuracy | Throughput | Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Physics-based, molecular dynamics | High (R=0.7-0.8) | Low (hours-days/mutation) | Significant computational resources |

| FoldX | Empirical force field | Medium (R=0.6) | High (minutes/mutation) | Single structure |

| Robetta (Flex_ddG) | Physical energy function | Medium-High | Medium | Homology models acceptable |

| BudeAlaScan | Empirical free energy | Medium | High | Single structure or ensembles |

| Machine Learning (mCSM) | Statistical potentials | Medium | Very High | Structural features |

The performance metrics reveal inherent trade-offs between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, with more rigorous physics-based methods requiring substantially greater resources but generally providing superior correlation with experimental data [3] [14].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Implementation

Successful execution of alanine scanning studies requires access to specialized reagents and instrumentation. The following table details key solutions employed in experimental protocols:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Instruments

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Site-directed mutagenesis kit | Introduction of alanine substitutions | Commercial kits (QuickChange) |

| Expression vector | Recombinant protein production | pET, pcDNA systems |

| Expression host | Protein synthesis | E. coli, mammalian cells |

| Purification system | Protein isolation | Metal-affinity, FPLC |

| Binding assay platform | Affinity measurement | Fluorescence polarization, SPR, ELISA |

| Structural modeling software | Interface analysis | Modeller, Rosetta |

Alanine scanning mutagenesis remains an indispensable tool for quantitatively mapping functional epitopes and validating hot spot residues, despite the emergence of complementary methodologies. The technique's unique strength lies in its direct measurement of side-chain energetic contributions through rigorous binding assays, providing a thermodynamic foundation for understanding molecular recognition. While the resource-intensive nature of comprehensive scanning studies presents practical limitations, the strategic integration of computational pre-screening with focused experimental validation creates an optimized approach for contemporary research. As protein therapeutics and targeted drug discovery continue to advance, the precise energetic mapping enabled by alanine scanning will maintain its critical role in rational protein design and interaction interface characterization.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are vital to all biological processes, and identifying the key residues that drive these interactions—known as hot-spot residues—is crucial for understanding cellular function and advancing drug design [3]. Computational alanine scanning (CAS) has emerged as a rapid, in silico method to predict these residues by calculating the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) when a residue is mutated to alanine [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of five prominent CAS tools: FoldX, Robetta (Flex_ddG), mCSM, BeAtMuSiC, and BUDE Alanine Scanning (BudeAlaScan). Framed within a broader thesis on validating hot-spot residues, this article compares their methodologies, performance metrics, and experimental validation, supplying researchers and drug development professionals with data to inform their tool selection.

Methodology of Computational Alanine Scanning

Fundamental Principles

Computational alanine scanning is based on the thermodynamic principle that the binding free energy change (ΔΔG) upon mutating a residue to alanine quantifies its contribution to the protein-protein interaction [3]. A hot-spot residue is typically defined as one whose mutation to alanine causes a ≥2.0 kcal/mol drop in binding free energy [33]. These methods generally fall into two categories: physics-based/empirical energy functions (FoldX, Robetta Flex_ddG, BUDE Alanine Scanning) and statistical potentials/machine learning approaches (mCSM, BeAtMuSiC) [3].

Experimental Validation Workflow

The standard workflow for validating computational predictions involves experimental alanine scanning, which is time-consuming and costly [3] [33]. The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for hot-spot validation.

Tool Comparison: Mechanisms and Methodologies

The five tools employ distinct approaches, offering different trade-offs between speed, accuracy, and consideration of protein dynamics [3].

Table 1: Core Methodologies of the Five CAS Tools

| Tool | Underlying Method | Input Requirements | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Empirical force field [3] | Single structure (e.g., from X-ray crystallography) [3] | Rapid calculations; widely used; empirical potentials [3] [34] |

| Robetta (Flex_ddG) | Physical energy function (Rosetta Ref2015/Talaris2014) [3] | Single structure [3] | Sophisticated Monte Carlo sampling & minimization; high accuracy [3] |

| mCSM | Machine learning (graph-based signatures) [3] | Single structure [3] | Uses signature patterns of the protein environment; trained on SKEMPI [3] |

| BeAtMuSiC | Statistical potentials [3] | Single structure [3] | Coarse-grained predictor; statistical potentials derived from known structures [3] |

| BUDE Alanine Scanning (BudeAlaScan) | Empirical free-energy (BUDE force field) [3] | Single structures or ensembles (NMR, MD) [3] | Handles structural ensembles; scans multiple mutations simultaneously [3] |

Performance and Benchmarking

A comparative analysis using the SKEMPI database—a comprehensive collection of binding free energy changes upon mutation—reveals variations in predictive accuracy and computational speed [3].

Table 2: Performance Metrics on the SKEMPI Database

| Tool | Pearson Correlation (ΔΔG) | Computational Speed | Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Data available in source [3] | ~8 minutes (single core) [3] | Fast but can suffer from lower accuracy, especially in antibody-antigen systems [34] |

| Robetta (Flex_ddG) | Data available in source [3] | ~1-2 hours per mutation (single core) [3] | High accuracy but computationally intensive; not ideal for high-throughput screening [3] |

| mCSM | Data available in source [3] | Not specified | Good performance; machine learning approach trained on structural data [3] |

| BeAtMuSiC | Data available in source [3] | Not specified | Uses statistical potentials; performance benchmarked on SKEMPI [3] |

| BUDE Alanine Scanning | Data available in source [3] | ~5 minutes (single core) [3] | Fast; unique capability to process structural ensembles from NMR or MD [3] |

A notable finding is that a consensus approach—averaging the ΔΔG values for each residue across the five methods—often leads to more accurate prediction than any single method alone [3].

Experimental Validation Case Studies

Validation on Diverse Protein Complexes

The comparative predictive capability of these tools was tested through detailed experimental analyses on three diverse PPI targets [3]:

- NOXA-B/MCL-1: An α-helix-mediated PPI, relevant in oncology [3].

- SIMS/SUMO: A β-strand-mediated interaction involved in SUMOylation regulation [3].

- GKAP/SHANK-PDZ: A β-strand-mediated scaffolding interaction at synaptic junctions [3].

For these targets, the computational predictions were followed by experimental alanine scanning to measure the actual ΔΔG values, validating the in silico predictions [3]. The consensus approach proved particularly effective across these diverse interfaces [3].

Workflow for Target Validation

The process for validating predictions on a target like the NOXA-B/MCL-1 complex involves a multi-stage workflow, integrating computational predictions with experimental assays.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key databases, software, and experimental reagents essential for conducting and validating computational alanine scanning studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Function in CAS Research |

|---|---|---|

| SKEMPI/SKEMPIv2.0 | Database [3] [34] | Curated database of binding free energy changes upon mutation; used for training and benchmarking CAS tools [3] [34] |

| ProTherm | Database [3] [34] | Database of thermodynamic data for protein stability and mutations; used for folding stability benchmarks [3] |

| PDB Fixer | Software Tool [34] | Pre-processes 3D crystal structures for CAS by adding missing residues and heavy atoms, and correcting errors [34] |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software Suite [35] | Commercial software that can perform site-directed mutagenesis computations, including alanine scanning [35] |

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis Kit | Experimental Reagent | Commercial kits for performing site-directed mutagenesis to create alanine variants for experimental validation |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Experimental Instrument | Measures real-time binding affinity (KD) of wild-type and mutant proteins to determine experimental ΔΔG [34] |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field of computational alanine scanning continues to evolve. Recent efforts focus on integrating machine learning to correct and improve existing force fields. For instance, a neural network framework applied to FoldX output significantly improved its correlation with experimental data, especially for higher-order mutations [34]. Another trend involves predicting hot spots from free protein structures (without the bound complex). Tools like PPI-hotspotID, which uses machine learning with features like conservation, amino acid type, and solvent accessibility, show promise in this area [33]. The integration of AlphaFold-predicted structures with these methods further expands the potential for probing PPIs where experimental structures are unavailable [33]. Finally, the ability to handle structural ensembles from NMR or molecular dynamics simulations, as seen in BUDE Alanine Scanning, provides a crucial avenue for accounting for protein dynamics and disordered regions in PPI analysis [3].

The identification of hot spot residues—a small subset of amino acids that contribute disproportionately to binding free energy—is crucial for understanding protein interactions and guiding drug discovery. While traditionally applied to protein-protein interactions (PPIs), alanine scanning mutagenesis is now being extended to map protein-lipid interactions, a frontier in membrane protein biology. This guide compares experimental and computational approaches for hot spot validation, focusing on their application in characterizing lipid binding sites on membrane proteins. We provide objective performance comparisons and detailed methodologies to help researchers select appropriate techniques for studying these critical interactions.

Most cellular processes involve complex protein interactions, with a small fraction of interfacial residues termed "hot spots" contributing the majority of binding free energy [1]. A residue is defined as a hot spot when its mutation to alanine causes a decrease in binding free energy (ΔΔG) of ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol [1]. Alanine scanning mutagenesis, the experimental gold standard for identifying these residues, systematically substitutes individual amino acids with alanine, removing side-chain atoms past the β-carbon without introducing conformational flexibility or steric effects [1] [36].

The composition of hot spots is distinctive, with tryptophan (21%), arginine (13.3%), and tyrosine (12.3%) occurring with high frequency due to their unique physicochemical properties [1]. These residues often form cooperative, structurally conserved networks that make attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [1].

While classical alanine scanning has revolutionized the study of soluble protein complexes, extending this methodology to membrane protein-lipid interactions presents unique challenges and opportunities. Membrane proteins, which constitute over 30% of the human proteome and represent a major class of drug targets, rely on specific lipid interactions for their structure, function, and stability [37] [38]. This guide compares established and emerging methods for hot spot validation in the context of protein-lipid interactions.

Computational Prediction of Hot Spots

Computational approaches provide valuable alternatives to experimental alanine scanning, offering greater throughput and lower cost. These methods predict binding free energy changes (ΔΔG) upon alanine mutation using various algorithms and force fields.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Hot Spot Prediction Methods

| Method | Approach | Features | Performance (Pearson Correlation) | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Empirical force field | Physical energy terms | 0.55-0.65 | High (minutes) |

| Rosetta Flex_ddG | Physical energy function with sampling | Talaris2014/Ref2015 force fields | 0.60-0.70 | Low (hours per mutation) |

| mCSM | Machine learning | Signature-based patterns | 0.60-0.65 | High |

| BeAtMuSiC | Statistical potentials | Coarse-grained potentials | 0.55-0.62 | High |

| BudeAlaScan | Empirical free energy | BUDE force field, ensemble processing | 0.58-0.63 | Medium (minutes) |

Table 2: Practical Considerations for Method Selection

| Method | Best For | Limitations | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Quick assessments, large interfaces | Limited conformational sampling | Standalone tool & server |

| Rosetta Flex_ddG | High-accuracy predictions, flexible interfaces | Computationally intensive, requires expertise | Standalone package |

| mCSM | Rapid screening, non-experts | Dependent on training data coverage | Web server |

| BeAtMuSiC | Conservative estimates, initial screening | May miss subtle effects | Web server |

| BudeAlaScan | Structural ensembles, multiple mutations | Newer method, limited validation | Command-line tool |

Comparative analyses reveal that consensus approaches, which average predictions across multiple methods, often outperform individual tools [3]. For membrane protein-lipid interactions, computational methods must account for the unique membrane environment, with tools like FoldX and Rosetta requiring adaptation for lipid bilayers.

Experimental Alanine Scanning for Protein-Lipid Interactions

Traditional alanine scanning faces challenges when applied to membrane proteins, particularly due to difficulties in protein solubilization, purification, and stability in detergent micelles [38]. Recent advances have adapted this methodology specifically for mapping protein-lipid interactions.

Native Mass Spectrometry Approach

Jayasekera et al. developed an innovative native mass spectrometry (MS) method to profile lipid binding sites on Aquaporin Z (AqpZ), a bacterial water channel [37] [39] [40]. This approach quantifies the thermodynamic contributions of specific residues to lipid binding.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Native MS Alanine Scanning

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| AqpZ mutants | Target membrane protein with systematic alanine substitutions |

| Tetraethylene glycol monooctyl ether (C8E4) | Mild detergent for protein solubilization and stabilization |

| Ammonium acetate buffer (0.2 M) | Volatile buffer compatible with native MS |

| Cardiolipin (POCL, TOCL) | Anionic lipid species for binding studies |

| Phosphatidylglycerol (POPG) | Comparison anionic lipid |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE) | Zwitterionic phospholipid control |

| Q-Exactive HF UHMR Orbitrap | High-resolution mass spectrometer for native MS |

Experimental Workflow:

- Mutant Selection and Design: Residues are selected based on: (1) prior known lipid-interacting residues (e.g., W14), (2) hydrophobic residues likely interacting with lipid tails (e.g., F10, F13, F196), and (3) cationic residues at the lipid interface that could interact with anionic headgroups (e.g., R3, R75, R224) [37].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Selected residues are systematically mutated to alanine using primer-based mutagenesis.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Mutant proteins are expressed in E. coli C43 cells and purified in C8E4 detergent to maintain native structure.

- Sample Preparation for Native MS: Wild-type and mutant proteins are mixed at approximately 1:1 molar ratio with added lipids at specific protein:lipid ratios (1:1:50 for cardiolipins, 1:1:100 for weaker-binding lipids).

- Data Acquisition: Mass spectra are acquired using temperature ramping from 15-35°C with key settings including spray voltage of 1.2 kV and collision voltage of 75-85 V.

- Data Analysis: Peak areas for lipid-bound and unbound states are quantified using UniDec and custom Python scripts. The dissociation constant ratio (K) and free energy difference (ΔΔG) are calculated using the equations:

- K = [W] × [ML] / [WL] × [M]

- ΔΔG = -RTlnK where W and M represent wild-type and mutant proteins, and WL and ML represent their lipid-bound states [37].

This native MS approach revealed that AqpZ is selective toward cardiolipins at specific sites, with CL orienting with its headgroup facing the cytoplasmic side and its acyl chains interacting with a hydrophobic pocket at the monomeric interface [37] [40].

Integrated Workflow: Combining Native MS with Molecular Dynamics

The most powerful applications combine experimental alanine scanning with computational simulations:

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Mapping Protein-Lipid Interactions

This integrative approach provides unique insights into lipid binding sites and selectivity, enabling researchers to map protein structure based on lipid affinity [37] [40]. For AqpZ, this revealed that cardiolipin orients with its headgroup facing the cytoplasmic side, with acyl chains interacting specifically with a hydrophobic pocket at the monomeric interface within the lipid bilayer [37].

Performance Comparison and Validation

Accuracy of Computational Predictions

When benchmarked against experimental data from the SKEMPI database (containing 3,047 binding free energy changes upon mutation), computational methods show varying performance levels:

Prediction Accuracy Metrics:

- FoldX: Moderate accuracy (Pearson correlation ~0.55-0.65), fast execution (~8 minutes for typical interface) [3]

- Rosetta Flex_ddG: Higher accuracy (Pearson correlation ~0.60-0.70), but computationally intensive (1-2 hours per mutation) [3]

- BudeAlaScan: Balanced approach (Pearson correlation ~0.58-0.63), medium throughput (~5 minutes), capable of processing structural ensembles [3]

- Consensus approaches: Typically outperform individual methods by averaging predictions across multiple tools [3]

For membrane protein-lipid interactions, accuracy may be reduced due to limited structural data and challenges in modeling the membrane environment.

Experimental Validation

Computational predictions require experimental validation. For the AqpZ study, native MS alanine scanning identified W14 as contributing to the highest affinity CL binding site, with R224 contributing to a secondary site [37]. These findings were validated through complementary molecular dynamics simulations showing high lipid occupancy and residence times at these residues.

The combination of native MS with MD simulations creates a powerful validation cycle: computational predictions guide experimental targets, while experimental results refine computational models. This approach confirmed CL selectivity at specific AqpZ sites and elucidated the molecular orientation of bound lipids [37] [40].

Extending alanine scanning to protein-lipid interactions represents a significant advancement in membrane protein biology. While computational methods offer rapid screening capabilities, integrated approaches that combine computational predictions with experimental validation provide the most robust strategy for identifying lipid interaction hot spots.

For researchers studying membrane protein-lipid interactions, we recommend:

- Initial Screening: Use consensus computational approaches (e.g., FoldX + mCSM + BudeAlaScan) to identify potential hot spot residues.

- Experimental Validation: Apply native MS-based alanine scanning to quantify binding contributions of selected residues.

- Mechanistic Insight: Complement with molecular dynamics simulations to visualize lipid interactions and understand molecular orientation.

- Functional Assessment: Corrogate identified hot spots with functional assays to establish physiological relevance.

This multifaceted approach enables comprehensive mapping of protein-lipid interactions, providing critical insights for drug discovery and understanding membrane protein function in health and disease. As methods continue to advance, particularly in cryo-EM and computational modeling, our ability to precisely characterize these interactions will further improve, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Best Practices for Selecting Residues to Mutate

A central goal in molecular biology and drug development is understanding the relationship between protein structure and function. A powerful approach to probing this relationship is alanine scanning mutagenesis, a method designed to identify "hot spot" residues—those where mutation significantly disrupts protein function or binding affinity [41] [42]. This technique systematically substitutes target residues with alanine, effectively removing side-chain atoms past the beta-carbon, thereby testing the functional contribution of the native side chain without introducing major conformational distortions [42]. Selecting the right residues to mutate is critical for efficient experimental design. This guide compares the performance of computational prediction tools with experimental alanine scanning and provides best-practice protocols for validating hot-spot residues.

Performance Comparison: Computational Predictions vs. Experimental Alanine Scanning

Selecting residues for mutagenesis often begins with in silico predictions before moving to costly experimental validation. The table below objectively compares the performance of different methodological approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Residue Selection and Mutagenesis Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Throughput | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Alanine Scanning (e.g., SNAP) | Predicts functional effects of mutations using neural networks [41]. | Very High (exhaustive in silico mutagenesis feasible) | ~70% sensitivity for hot spots (ΔΔG ≥1 kcal/mol); higher accuracy for severe changes [41]. | Fast, low-cost; can probe all residues and all possible amino acid substitutions [41]. | Predictions require experimental validation; accuracy can vary. |

| Experimental Alanine Scanning | Measures binding energy change (ΔΔG) after substituting a residue with alanine [41] [42]. | Low (each mutant expressed and assayed separately) [42]. | Identifies hot spots based on empirical energy thresholds (e.g., ΔΔG ≥1 kcal/mol) [41]. | Gold standard for defining functional epitopes and energetic contributions [42]. | Laborious, costly, and low-throughput [42]. |

| Shotgun Scanning | Phage-displayed combinatorial library with binomial substitution (wild-type or alanine) at multiple positions [42]. | High (large libraries >10^10 clones screened via binding selection) [42]. | Identifies hot spots via enrichment ratios (Ala/WT) from sequencing, correlating with ΔΔG [42]. | Rapidly maps functional epitopes; combines throughput of libraries with functional insight of alanine scanning [42]. | Requires phage display expertise; indirect measurement of energy change. |

| Base Editing (BE) Screens | Uses CRISPR base editors to make endogenous transitions (C>T or A>G) guided by sgRNA pools [43]. | High (surrogate genotyping via sgRNA sequencing) [43]. | Correlation with gold-standard DMS data; quality depends on filters for single-edit sgRNAs [43]. | Endogenous genomic context; scalable across cell lines [43]. | Limited to transition mutations; bystander edits; PAM sequence requirements [43]. |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) | Heterologous expression of saturated cDNA mutant libraries [43]. | High | Comprehensive measurement of all amino acid substitutions [43]. | Broad mutational repertoire; well-established analysis [43]. | Non-endogenous expression; potential scaling challenges with large genes [43]. |