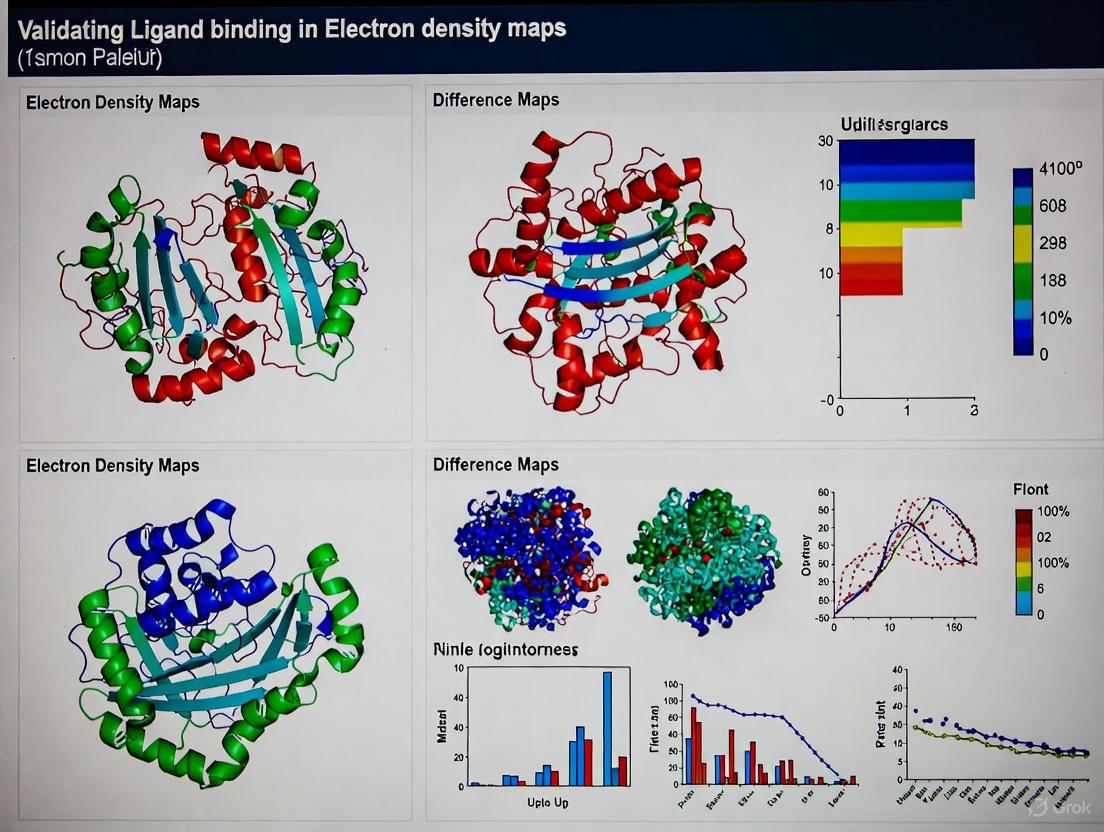

Validating Ligand Binding in Electron Density Maps: A Guide to Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices

Accurately identifying and validating small-molecule ligands in experimental density maps from techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a critical yet challenging step in structure-guided drug design.

Validating Ligand Binding in Electron Density Maps: A Guide to Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices

Abstract

Accurately identifying and validating small-molecule ligands in experimental density maps from techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a critical yet challenging step in structure-guided drug design. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of ligand validation, modern computational methods including deep learning, strategies for troubleshooting common issues in map interpretation, and a comparative analysis of validation metrics and benchmarks. By synthesizing recent advancements, such as those from the 2024 EMDataResource Ligand Challenge, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to improve the reliability of their structural models and avoid the pitfalls of misidentified ligands.

The Critical Foundation: Why Ligand Validation is Essential in Structural Biology

The Central Role of Ligands in Understanding Protein Function and Drug Mechanism

Protein-ligand interactions represent a fundamental molecular mechanism governing critical biological processes in living organisms. These interactions, which involve the formation of complexes between proteins and ligands (small molecules or other macromolecules), are indispensable for enzyme catalysis, signal transduction, gene regulation, and molecular recognition [1]. The precise binding of ligands to protein targets initiates conformational changes that modulate protein function, making this process a cornerstone for understanding cellular physiology and pathology. From a therapeutic perspective, the majority of pharmaceutical compounds function as ligands that selectively bind to protein targets to alter their activity, underscoring the pivotal role of ligand interactions in drug discovery and development [1] [2].

The study of these interactions has evolved significantly from Emil Fischer's 1894 "lock-and-key" principle to contemporary understanding that incorporates induced-fit mechanisms and conformational selection dynamics [1]. Modern research has revealed that protein-ligand interactions exhibit remarkable complexity, involving weak and transient binding, allosteric modulation, and multivalent interactions that enhance affinity and specificity [1]. The accurate characterization of these interactions provides invaluable insights for rational drug design, enabling researchers to develop therapeutic agents with optimized binding affinity, specificity, and pharmacokinetic properties.

Computational Methods for Predicting Ligand Binding

Computational approaches for predicting protein-ligand interactions have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery, offering cost-effective and scalable strategies for exploring chemical and biological spaces [3]. These methods span various techniques, from traditional physics-based simulations to cutting-edge machine learning algorithms, each with distinct strengths and limitations for specific applications in structure-based drug design.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Prediction Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Ligand Binding Site Prediction

| Method Name | Method Type | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LABind [2] | Structure-based (Multi-ligand) | Graph transformer with cross-attention mechanism; ligand-aware binding site prediction | AUPR: 0.72 (DS1), 0.70 (DS2); Effective for unseen ligands | Requires protein structure information |

| LigBind [2] | Structure-based (Single-ligand) | Pre-training on broad ligand sets; requires fine-tuning for specific ligands | Limited effectiveness without fine-tuning | Cannot predict sites for completely unseen ligands without retraining |

| P2Rank/DeepPocket [2] | Structure-based (Multi-ligand) | Relies on protein structure features (e.g., solvent accessible surface) | Moderate performance across diverse ligands | Ignores ligand-specific binding patterns |

| SEGSA_DTA [4] | Affinity Prediction | SuperEdge graph convolution; supervised attention for protein-ligand interactions | Outperforms state-of-the-art affinity prediction methods | Specifically designed for affinity prediction, not binding site identification |

| ENTess QSBR [5] | Affinity Prediction | Delaunay tessellation with electronegativity descriptors; k-Nearest Neighbor QSBR | Cross-validated R²: 0.83 (test set), 0.85 (validation set) | Traditional QSAR approach with limited applicability to diverse complexes |

Experimental Protocols for Binding Affinity Prediction

The ENTess QSBR (Quantitative Structure-Binding Relationship) method employs a well-defined protocol for binding affinity prediction [5]. The methodology begins with dataset preparation, involving the collection of high-resolution (below 3.0Å) X-ray crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes from the PDB. Hydrogen atoms and water molecules are removed, and ligands are extracted using molecular modeling software such as SYBYL. Delaunay tessellation is then applied to the protein-ligand interface, partitioning the 3D structure into space-filling, irregular tetrahedra (simplices) with atoms as vertices. Each atomic quadruplet composition is characterized by a single descriptor calculated as the sum of the Pauling electronegativity values for the four participating atom types. These ENTess descriptors serve as independent variables in k-Nearest Neighbor QSBR studies, with models validated through rigorous training/test set splits and leave-one-out cross-validation.

For SEGSA_DTA implementation, the protocol involves several key steps [4]. First, protein and ligand structures are converted into graph representations with comprehensive edge features. The SuperEdge graph convolution then fuses node and edge information to capture intricate structural relationships. A multi-supervised attention module learns attention distributions consistent with real protein-ligand interactions, with model interpretability enhanced through SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis. Training incorporates multi-task learning on binding affinity datasets, with performance evaluated using root mean square error (RMSE) and correlation coefficients on benchmark datasets.

Experimental Validation of Ligand Binding

Experimental validation of protein-ligand interactions provides the critical foundation for computational method development and verification. Structural biology techniques, particularly X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), enable direct visualization of ligand binding modes and interactions at atomic or near-atomic resolution.

Ligand Validation in Electron Density Maps

The LigPCDS dataset provides a standardized framework for validating ligand binding in electron density maps [6]. This comprehensive dataset contains 244,226 ligand entries derived from X-ray protein crystallography data deposited in the Protein Data Bank. The experimental workflow for creating and validating LigPCDS involves several critical steps. First, a list of valid ligands is filtered and downloaded from the RCSB PDB. Entries are refined using Dimple v2.6.1 in a standardized procedure without added heteroatoms to normalize data quality and highlight ligand blobs in Fo-Fc maps. The 3D images of ligands are derived from their Fo-Fc maps using Gemmi v0.5.8 based on atomic positions of ligand entries. These representations are converted to 3D point clouds with appropriate scaling, background removal, masking, and contouring. Finally, ligand 3D point clouds are labeled pointwise using atomic sphere modeling and designed chemical vocabularies based on atoms and their cyclic structural arrangements [6].

Deep learning models trained on the LigPCDS dataset demonstrate robust performance in semantic segmentation of ligand 3D representations, achieving mean accuracy ranging from 49.7% to 77.4% in terms of Intersection over Union (mIoU) metric and from 62.4% to 87.0% in F1-score (mF1) across different chemical vocabularies [6]. This validation confirms the reliability of the dataset and methodology for interpreting protein ligand chemical structures from experimental data.

High-Quality Dataset Curation

The HiQBind-WF workflow addresses critical challenges in protein-ligand dataset quality that impact validation accuracy [7]. This semi-automated workflow implements multiple curation modules: (1) filtering to reject covalent protein-ligand bonds, rare elements, and severe steric clashes; (2) ligand fixing to ensure correct bond order and protonation states; (3) protein fixing to add missing atoms to binding-related chains; and (4) structure refinement to simultaneously add hydrogens to both proteins and ligands in complex state. Application of HiQBind-WF to existing datasets like PDBbind demonstrates its ability to correct structural imperfections that compromise scoring function accuracy and reliability [7].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein-Ligand Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LigPCDS Dataset [6] | Experimental Dataset | 3D point clouds of protein ligands from X-ray crystallography | 244,226 ligand entries; chemically labeled point clouds | Derived from PDB; Available through publication |

| HiQBind Dataset [7] | Curated Dataset | High-quality protein-ligand structures with binding affinities | >18,000 unique PDB entries; structural artifacts corrected | Open-source workflow and dataset |

| PDBbind [7] | Reference Dataset | Biomolecular complexes with binding affinities | ~19,500 complexes; general/refined/core subsets | http://www.pdbbind-cn.org/ (v2020) |

| BindingDB [7] | Binding Affinity Database | Protein-ligand binding measurements | 2.9 million measurements; 1.3 million compounds | Public database |

| BioLiP [7] | Protein-Ligand Database | Biologically relevant protein-ligand interactions | >900,000 interactions; functional annotations | Public database |

Integration of Computational and Experimental Approaches

The most significant advances in protein-ligand interaction research emerge from the strategic integration of computational predictions with experimental validation. This synergistic approach enables researchers to overcome the limitations inherent in each methodology when used independently.

Signaling Pathways Initiated by Ligand Binding

Ligand binding events typically initiate complex signaling cascades that regulate critical cellular processes [8]. These molecular pathways represent sequences of reactions, often starting with ligand binding to receptors, which subsequently triggers intracellular signaling events. Visualization of these pathways employs specific color semantics, where analogous color palettes (colors adjacent on the color wheel) indicate molecular components that are functionally connected within the same pathway, while color progressions signify the sequential order of molecular interactions [8].

Best Practices for Method Selection

Research objectives should guide the selection of computational and experimental methods for studying protein-ligand interactions. For predicting binding sites for novel ligands, ligand-aware methods like LABind are recommended due to their ability to generalize to unseen ligands [2]. When working with established ligands with known binding sites, affinity prediction methods such as SEGSA_DTA or traditional QSBR approaches may provide sufficient accuracy [4] [5]. For structure-based drug design projects that require atomic-level precision, high-quality curated datasets like HiQBind combined with experimental validation through X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM offer the most reliable approach [7] [6].

The field continues to evolve with emerging trends including the study of ligands targeting intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) - challenging therapeutic targets involved in incurable cancers and neurodegenerative disorders [1]. Advanced deep learning models like AlphaFold 3, RosettaFold All-Atom, and molecular diffusion models are increasingly capable of predicting protein-ligand complex structures with accelerating accuracy, potentially revolutionizing virtual screening and de novo drug design in the coming years [1].

The high-resolution visualization of protein-ligand complexes is fundamental to understanding biological function and advancing structure-based drug design. Two primary experimental techniques—X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)—provide atomic-level insights into these interactions, yet they diverge significantly in their methodological approaches, capabilities, and limitations for ligand modeling. While X-ray crystallography has long been the cornerstone of structural biology, offering unparalleled throughput and resolution for crystallizable targets [9], recent breakthroughs in cryo-EM have enabled the determination of complex biomolecules previously inaccessible to crystallization [10]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these techniques for ligand modeling, framed within the broader thesis of validating ligand binding in electron density maps. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical resources to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate technique for their specific structural biology questions.

Technical Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core technical characteristics and typical performance metrics of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM for ligand modeling applications.

Table 1: Key technical characteristics of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM for ligand modeling

| Characteristic | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution Range | Often 1.5 - 3.0 Å [9] | Often 2.5 - 4.0 Å for ligands, even with 1.5 Å protein resolution [11] |

| Sample State | Crystalline lattice | Vitreous ice (single particles) |

| Temperature Regime | Cryogenic (100 K) standard; Room-temperature emerging [9] [12] | Cryogenic (~100 K) |

| Ligand Introduction Methods | Co-crystallization; Crystal soaking [13] | Incubation with purified protein prior to vitrification |

| Throughput | High (highly automated) [9] | Moderate (rapidly improving) |

| Ideal for Membrane Proteins | Challenging, requires specialized crystallization [10] | Excellent [14] |

| Ability to Trap Intermediates | Yes (via kinetic trapping in crystals) [13] | Limited |

| Radiation Damage Concerns | Mitigated by cryo-cooling; higher at room temperature [9] [12] | Mitigated by low dose imaging and particle averaging |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Modeling

X-ray Crystallography Workflow

Sample Preparation: Protein-ligand complexes for X-ray crystallography are typically generated via co-crystallization (mixing protein and ligand prior to crystal growth) or soaking (introducing the ligand into pre-grown native crystals) [13]. Soaking is more common for high-throughput applications like fragment-based screening [9].

Data Collection: The standard method involves collecting a single, complete diffraction dataset from one or a few cryo-cooled (100 K) crystals. However, serial crystallography at synchrotrons or XFELs is an emerging method. It merges data from thousands of microcrystals, which is particularly beneficial for room-temperature data collection as it minimizes radiation damage [9] [12].

Ligand Building and Refinement: The initial protein model is fit into the electron density map. The ligand is then modeled into the residual difference density ( Fo - Fc ) in the binding site. Due to conformational heterogeneity, tools like qFit-ligand can be employed. This algorithm uses RDKit's ETKDG method for stochastic conformational sampling and selects a parsimonious ensemble of conformers that best fit the electron density, which is especially useful for flexible ligands and macrocycles [15].

Cryo-EM Workflow

Sample Preparation: The protein is incubated with the ligand in solution, and the complex is then vitrified for data collection. The absence of a crystal lattice can more readily accommodate conformational changes in the protein upon ligand binding [14].

Data Collection & Processing: Thousands of micrographs are collected and processed to reconstruct a 3D density map. A significant challenge is that the global resolution of the map can be high, but the local resolution around the bound ligand is often lower, making ligand identification and modeling difficult [11].

Ligand Building and Refinement: A powerful emerging approach integrates artificial intelligence (AI) with density-guided molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [11] [16].

- AI Prediction: An AI model, such as an AlphaFold3-like model (e.g., Chai-1), predicts the structure of the protein-ligand complex using the protein sequence and the ligand's SMILES string [11].

- Flexible Fitting: The AI-predicted model is then flexibly fit into the experimental cryo-EM map using MD simulations. Additional forces guide the atoms to maximize the cross-correlation between the simulated density of the model and the experimental map, refining both the protein and ligand poses simultaneously [11]. This hybrid approach has been shown to improve ligand model-to-map cross-correlation from 40-71% to 82-95% relative to the deposited structure [11] [16].

Workflow Visualization

The diagrams below illustrate the core methodological workflows for ligand modeling in both techniques, highlighting key differences in approach.

X-ray Crystallography Ligand Modeling

Cryo-EM Ligand Modeling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful ligand modeling requires a suite of specialized computational tools and reagents. The table below details key solutions for both techniques.

Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for ligand modeling

| Category | Item / Software | Primary Function | Applicable Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Refinement | qFit-ligand [15] | Automated modeling of multiconformer ligands into electron density. | X-ray, Cryo-EM |

| RDKit (ETKDG) [15] | Stochastic generation of chemically sensible small molecule conformers. | X-ray, Cryo-EM | |

| GROMACS [11] | Molecular dynamics package for density-guided flexible fitting. | Cryo-EM | |

| AI Prediction | AlphaFold3 / Chai-1 [11] | Predicts protein-ligand complex structure from sequence and SMILES. | Cryo-EM |

| Data Processing | PanDDA [15] | Identifies low-occupancy ligands in X-ray data by subtracting background density. | X-ray (Fragment Screening) |

| Ligand Specification | SMILES String [11] | Standardized line notation for inputting ligand chemistry into modeling software. | X-ray, Cryo-EM |

| Sample Handling | Microporous Fixed-Target Chips [9] | High-throughput serial crystallography at room temperature. | X-ray (SSX) |

Both X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM are powerful techniques for determining protein-ligand structures, yet they offer complementary strengths. X-ray crystallography remains the workhorse for high-throughput studies of crystallizable targets, providing high-resolution data that enables the modeling of subtle ligand conformational heterogeneity [15] [9]. The emergence of room-temperature serial techniques is further enhancing its physiological relevance [12]. In contrast, cryo-EM has revolutionized the study of large complexes and membrane proteins, such as GPCRs and ion channels, which are often recalcitrant to crystallization [14]. Its main challenge for ligand modeling—lower local resolution at the ligand site—is being effectively addressed by innovative hybrid approaches that combine AI-based prediction with experimental density-guided simulation [11] [16]. The choice between techniques depends ultimately on the biological target, the scientific question, and available resources. Future progress will likely be driven by deeper integration of these experimental methods with computational tools, leading to more dynamic and accurate models of molecular recognition.

In the field of structural biology, accurately determining how a small molecule ligand binds to its protein target is fundamental to understanding biological function and for rational drug design. However, this process is susceptible to a range of pitfalls, from ingrained cognitive biases to the technical limitations of experimental data. This guide objectively compares the realities of ligand binding validation against the ideal, providing researchers with the data and methodologies needed to critically assess structural models.

The Impact of Cognitive Bias on Structural Interpretation

Cognitive biases systematically skew the interpretation of experimental data, leading to overconfidence in initial models.

- Confirmation Bias: Scientists naturally tend to favor information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. In crystallography, this can manifest as building a ligand model to fit weak or ambiguous electron density because it is the expected compound, potentially overlooking discrepancies [17].

- The "Single Structure" Paradigm: A conservative view that insists on "a single dataset, a single structure, a single interpretation" can hinder progress. This mindset may cause researchers to dismiss more complex, multi-state models that better represent the compositional and conformational heterogeneity present in the crystal, especially in fragment-screening campaigns [18].

- The "Flexibilization" of Science: Under external pressures, such as the urgent need for treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic, methodological standards can loosen. This "flexibilization" creates a vicious cycle where low-quality studies produce unreliable data, which in turn generates anecdotal evidence that reinforces pre-existing beliefs [17].

Technical Limitations: The Illusion of High Resolution

Global quality metrics like resolution are often relied upon as a proxy for overall model quality, but they can be dangerously misleading for local ligand interpretation.

Table 1: Prevalence of Ligand Quality Issues in the PDB

| Quality Category | Percentage of Ligands | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Good | 27% | Highly reliable; minimal concerns for use [19]. |

| Dubious | 51% | Not highly reliable; poses minor quality concerns [19]. |

| Bad | 22% | Needs serious attention; unsuitable for applications like drug design [19]. |

A critical analysis of approximately 0.28 million protein-ligand pairs from the PDB reveals that a significant portion of ligands have quality issues [19]. Alarmingly, over half (62.5%) of the ligands classified as "Bad" were determined at a high resolution of 2.5 Å or better [19]. This demonstrates that a high-resolution structure does not guarantee a correct ligand model.

Furthermore, high-resolution studies on Fatty Acid-Binding Proteins (FABPs) uncovered that an estimated 15% of the well-defined ligands had a different chemical composition than expected [20]. These "unexpected ligands" resulted from issues like synthesis side products, degradation, or human error during compound registration. At lower resolutions, these subtle chemical changes can easily go unnoticed, leading to misidentified binding poses that corrupt structure-based design and machine-learning training sets [20].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

To mitigate bias and technical limitations, rigorous and objective validation protocols are essential. The following workflows provide a framework for confident ligand modeling.

Experimental Protocol 1: Validating Ligand Pose and Identity in Cryo-EM Maps

Objective: To accurately identify and build a small molecule ligand into a medium-resolution cryo-EM density map. Background: Cryo-EM is increasingly used for structure-based drug design, but ligand modeling at typical resolutions (worse than 3 Å) is challenging. Traditional crystallographic methods perform poorly at these resolutions [21].

Methodology: The EMERALD-ID method uses a combination of physical forcefields and density agreement to rank ligand identities from a user-provided library [21].

- Input: Provide the cryo-EM density map, a receptor model, and a library of potential ligand identities.

- Docking: The EMERALD tool docks all candidate ligands from the library into the target density map [21].

- Evaluation: A scoring function combines the RosettaGenFF small molecule forcefield (estimating binding affinity) with the density correlation of the docked pose.

- Output: The method ranks the candidate ligands, providing the most probable identity and its conformation. In benchmarks, EMERALD-ID successfully identified the deposited ligand in 44% of instances, and a closely related ligand in 66% of cases [21].

Cryo-EM Ligand Identification Workflow

Experimental Protocol 2: Creating High-Quality Datasets for Computational Studies

Objective: To curate a high-quality, non-covalent protein-ligand dataset for reliable training and validation of scoring functions in drug discovery. Background: Widely used datasets like PDBbind can contain structural artifacts in both proteins and ligands, compromising the accuracy and generalizability of computational models [7].

Methodology: The HiQBind-WF is a semi-automated workflow for data cleaning and structural preparation [7].

- Initial Filtering: Reject covalent binders, ligands with rare elements, and structures with severe steric clashes.

- Ligand Fixing (LigandFixer): Correct bond orders, protonation states, and aromaticity to ensure ligand chemistry is correct.

- Protein Fixing (ProteinFixer): Add missing atoms and residues to all protein chains involved in binding.

- Structure Refinement: Recombine the fixed protein and ligand, then perform a constrained energy minimization to add hydrogens and resolve steric issues in the context of the complex. This workflow systematically addresses common errors, producing a more reliable dataset (HiQBind) for developing drug discovery tools [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following tools and resources are critical for conducting rigorous ligand validation.

Table 2: Key Tools for Ligand Validation and Analysis

| Tool Name | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| FLEXR-MSA | Unbiased electron-density map comparison of sequence-diverse structures [22]. | X-ray Crystallography |

| VHELIBS | Quantifies local structural quality of ligands and binding site residues [19]. | X-ray Crystallography |

| PDB-EDA | Converts sigma-scaled maps to absolute electron units for physicochemical interpretation [23]. | X-ray Crystallography |

| EMERALD-ID | Docks and evaluates small molecules to determine ligand identity in Cryo-EM maps [21]. | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

| HiQBind-WF | Semi-automated workflow to create high-quality protein-ligand datasets [7]. | Data Curation for Computational Drug Discovery |

| PanDDA | Identifies low-occupancy ligands by analyzing multiple datasets from screening campaigns [18]. | X-ray Crystallographic Fragment Screening |

Key Takeaways for Researchers

- Trust, but Verify: A high-resolution structure or a PDB code does not guarantee a correct ligand model. Always inspect the ligand's fit to the electron density.

- Embrace Complexity: Move beyond the "single structure" mindset. Consider that your crystal may contain multiple ligand states or conformations, especially in screening experiments.

- Leverage Automated Tools: Use the available computational toolkit to obtain an objective, quantitative assessment of ligand quality. Do not rely solely on visual inspection, which is susceptible to bias.

- Context is Key: The reliability of a ligand model is not just a function of resolution, but also of ligand occupancy, B-factors, and the chemical environment of the binding pocket.

By understanding these pitfalls and adopting rigorous validation protocols, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy of their structural models, leading to more reliable biological insights and a more efficient drug discovery process.

In structural biology, particularly in the context of validating ligand binding in electron density maps, the accuracy and precision of a molecular model are paramount. High-quality structural models serve as the foundation for understanding biological mechanisms and guiding drug development efforts. However, the process of building atomic models into electron density maps, especially those derived from X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), inherently involves interpretation that can be subjective. This challenge is particularly acute for ligand binding sites, which often exhibit lower resolution and higher flexibility than the protein backbone. Without robust, quantitative validation metrics, researchers risk basing scientific conclusions on modeling artifacts or inaccurate atomic placements.

This guide introduces four essential quality metrics—RSCC, RSZD, Q-score, and MolProbity—that provide complementary approaches for assessing model quality. These metrics help researchers move beyond subjective assessment to objective, quantitative evaluation of how well their structural models represent the experimental data and conform to established stereochemical rules. By understanding the strengths and applications of each metric, structural biologists and drug development professionals can make more informed decisions about model quality, particularly when characterizing ligand binding sites that are crucial for structure-based drug design.

Metric Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC)

The Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) quantifies how well the electron density calculated from an atomic model matches the experimentally observed electron density within a specific region of the map. It is defined as the sample correlation coefficient between the observed (ρobs) and calculated (ρcalc) electron density values at all grid points within a defined volume [24]:

RSCC = cov(ρobs, ρcalc) / √[var(ρobs) • var(ρcalc)]

where cov denotes covariance and var denotes variance. The RSCC ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating better agreement between model and experimental data [25]. In practice, RSCC is typically calculated on a per-residue basis, making it particularly valuable for assessing the fit of individual ligands or specific binding site residues [26]. However, it's important to note that RSCC values are influenced by both model accuracy and precision—they can be affected by factors like atomic displacement parameters (B-factors) and local map quality [24].

Real-Space Z-Difference Score (RSZD)

The Real-Space Z-Difference Score (RSZD) measures the statistical significance of features in the difference electron density map (Fo - Fc), which highlights areas where the model does not adequately explain the experimental data. Unlike RSCC, RSZD focuses specifically on model inaccuracies. The calculation involves analyzing the distribution of difference density values at grid points surrounding the atoms of interest [24]:

RSZD = max(|RSZD-|, RSZD+)

RSZD- and RSZD+ represent Z-scores for negative and positive difference density, respectively, computed by comparing the observed difference density values to the expected distribution. A high RSZD value (typically >3-4) indicates statistically significant unexplained density, suggesting potential modeling errors. The key advantage of RSZD is that it specifically measures model accuracy independently from precision-related parameters like B-factors [24].

Q-score

The Q-score is a metric developed specifically for assessing atom resolvability in cryo-EM maps, though the concept can be extended to crystallographic maps [27]. It quantifies how well individual atoms are resolved by measuring the sharpness of the electron density peaks at atomic positions. The Q-score ranges from 0 to 1, where a value of 1 indicates perfect resolvability of an atom. When averaged across entire models or specific regions, Q-scores correlate strongly with map resolution, providing a local and global measure of map quality [27]. For ligand binding validation, Q-scores are particularly valuable for determining whether the experimental evidence supports the placement of specific ligand atoms.

MolProbity

MolProbity is not a single metric but rather a comprehensive structure validation system that employs multiple criteria to evaluate model quality [28]. Its key components include:

- Clashscore: The number of serious steric overlaps per 1000 atoms, identifying atoms positioned unrealistically close to each other [29] [28]

- Ramachandran analysis: Evaluation of protein backbone torsion angles against preferred conformations [28]

- Rotamer analysis: Assessment of side-chain conformations against preferred rotamer libraries [28]

- Bond length and angle geometry: Comparison of covalent geometry to high-resolution reference data [29]

MolProbity employs all-atom contact analysis, including hydrogen atoms, making it exceptionally sensitive for identifying steric problems and validation outliers [28]. For ligand binding sites, MolProbity can identify clashes between ligands and protein atoms that might indicate incorrect placement.

Comparative Analysis of Quality Metrics

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Structural Validation Metrics

| Metric | Theoretical Range | Optimal Values | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSCC | 0 to 1 | >0.8 (good), >0.9 (excellent) | Local fit to density | Intuitive interpretation; Direct measure of fit to experimental data | Correlated with B-factors; Depends on both accuracy and precision |

| RSZD | 0 to ∞ | <3 (good), <4 (acceptable) | Identifying unmodeled features | Pure measure of model accuracy; Statistical framework | Less intuitive; Requires proper estimation of σ(Δρ) |

| Q-score | 0 to 1 | >0.8 (good), >0.9 (excellent) | Atom resolvability in maps | Direct measure of map quality; Correlates with resolution | More applicable to cryo-EM; Less established for crystallography |

| MolProbity | Varies by component | Clashscore: <10 (good), <20 (acceptable) | Overall model geometry | Comprehensive assessment; All-atom sensitivity | Does not directly assess fit to experimental data |

Table 2: Metric Performance Across Different Resolution Ranges

| Metric | High Resolution (<2.0 Å) | Medium Resolution (2.0-3.0 Å) | Low Resolution (>3.0 Å) | Ligand Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSCC | Highly discriminative | Reliable but less sensitive | Affected by ambiguity | Excellent for well-ordered ligands |

| RSZD | Highly sensitive to small errors | Good for identifying major errors | Challenging due to noisy maps | Excellent for identifying incomplete modeling |

| Q-score | Near 1 for most atoms | Declines for side-chain atoms | Limited utility | Directly measures ligand atom evidence |

| MolProbity | Stringent geometry assessment | Essential for guiding modeling | Critical for avoiding over-interpretation | Identifies steric conflicts with protein |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Calculating RSCC and RSZD with EDSTATS

The CCP4 program EDSTATS provides a standardized method for calculating RSCC and RSZD metrics [24]. The recommended protocol is:

Input Preparation: Gather your refined model (PDB format) and either a reflection file (MTZ) or a calculated electron density map (CCP4 format). For ligand-specific analysis, consider creating a separate PDB file containing just the binding site region.

Command Line Execution: Run EDSTATS with the following command structure:

Where MAPIN1 and MAPIN2 are the observed and calculated maps, and XYZIN is the input coordinate file [24].

Result Interpretation: Examine the output file for per-residue statistics. Focus on the ligand and binding site residues. For ligands, RSCC values below 0.8 typically indicate poor fit to density, while RSZD values above 3-4 suggest significant unmodeled features [24].

Implementing MolProbity Validation

MolProbity provides both web-based and command-line interfaces for comprehensive structure validation [28]:

Input Preparation: Prepare your coordinate file in PDB or mmCIF format. Ensure the file contains any ligands or cofactors to be validated.

Web Server Usage:

- Upload your coordinate file to http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu

- Select "Add H atoms" with automated Asn/Gln/His flip correction enabled

- Choose "Analyze all-atom contacts and geometry" for full validation

- Download results including Clashscore, Ramachandran, and rotamer analysis [28]

Analysis of Results: Pay special attention to clashes between ligands and protein atoms, which may indicate incorrect placement. For binding site residues, check for Ramachandran and rotamer outliers that might suggest strained conformations.

Q-score Calculation for Resolvability Assessment

The Q-score calculation methodology involves [27]:

Input Preparation: Obtain your cryo-EM map (MRC format) and fitted atomic model (PDB format). For ligand binding analysis, extract a submap focused on the binding site.

Software Implementation:

- Use the MapQ plugin for UCSF Chimera, available on GitHub

- Alternatively, implement the published algorithm which compares the experimental map to a simulated ideal map computed from the atomic model

- Calculate Q-scores for individual atoms, then average for residues or ligands

Interpretation: Q-scores below 0.7 for ligand atoms suggest limited resolvability, while scores above 0.8 indicate clear density support. These values should be considered in context with the overall map resolution.

Integrated Workflow for Ligand Binding Validation

Integrated Workflow for Ligand Binding Validation

The recommended workflow begins with an initial model containing the docked ligand. All four validation metrics should be calculated in parallel, as they provide complementary information. The results must be interpreted collectively—for instance, a ligand with acceptable RSCC but poor MolProbity clashscores may be correctly positioned but have steric issues that need resolution. Based on this integrated assessment, researchers decide whether the model requires refinement or can be considered validated.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Structural Validation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Ligand Validation | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCP4/EDSTATS | RSCC/RSZD calculation | Quantifying ligand fit to density | Command line [24] |

| MolProbity | Comprehensive validation | Identifying steric clashes and geometry issues | Web server/standalone [28] |

| Phenix | Integrated refinement and validation | Model-vs-data analysis during refinement | Command line/GUI [25] |

| UCSF Chimera | Visualization and analysis | Visual integration of validation metrics | GUI [27] |

| MapQ | Q-score calculation | Assessing ligand atom resolvability | Plugin for Chimera [27] |

Robust validation of ligand binding in electron density maps requires a multifaceted approach that combines multiple complementary metrics. RSCC provides a direct measure of how well the model explains the experimental density, RSZD identifies areas of potential omission or error, Q-score assesses the intrinsic resolvability of atoms in the map, and MolProbity ensures proper stereochemistry and absence of steric conflicts. By applying these metrics systematically through integrated workflows, researchers can substantially increase the reliability of their structural models, particularly in the critical context of ligand binding sites that inform drug discovery efforts. As structural biology continues to push toward more challenging targets, including membrane proteins and large complexes, these validation metrics will play an increasingly important role in ensuring the accuracy and biological relevance of structural models.

From Manual Fitting to AI: Modern Methods for Ligand Identification and Modeling

Validating ligand binding in electron density maps represents a critical step in structural biology and structure-based drug design. This process bridges the gap between experimental data and atomic models, ensuring the accuracy of structural interpretations that inform therapeutic development. Traditional computational methods for ligand fitting have long relied on search-and-score algorithms combined with crystallographic refinement, while emerging iterative approaches leverage advanced statistical sampling and deep learning to address complex challenges such as low-occupancy binding and protein flexibility. This guide provides an objective comparison of current methodologies, examining their performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and applicability across different research scenarios. As structural biology increasingly focuses on capturing dynamic processes and transient complexes, the evolution of these tools enables researchers to extract more biological insight from electron density data than ever before.

The landscape of ligand fitting methods spans multiple computational strategies, each with distinct theoretical foundations and workflow integration characteristics. The table below categorizes and compares the fundamental approaches available to researchers.

Table 1: Classification of Ligand Fitting Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Core Approach | Typical Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Density Analysis | Ringer, PanDDA | Electron density sampling and statistical comparison | Paired crystallographic datasets (perturbed and native) |

| Automated Model Building | qFit, Phenix-MD, FLEXR | Multi-conformer model building | Single crystal structure with electron density map |

| Iterative Denoising | METEOR | Total variation denoising with negentropy optimization | Difference map with optional reference structure |

| Deep Learning Docking | DiffDock, EquiBind, CWFBind | Geometric deep learning and diffusion models | Protein structure and ligand chemical representation |

| Cross-Map Comparison | FLEXR-MSA | Multiple sequence alignment coupled with density sampling | Multiple structures of sequence-diverse proteins |

The logical relationship between these methodological categories reveals an evolutionary trajectory in the field, from foundational density analysis to integrated learning systems that account for structural flexibility and diversity.

Figure 1: Methodological evolution in ligand fitting, showing the progression from fundamental density analysis to integrated validation approaches.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous benchmarking against standardized datasets provides critical insights into the operational performance of ligand fitting methods. The following table summarizes published performance data across multiple tool categories.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Ligand Fitting Approaches

| Tool | Method Type | Success Rate | Resolution Range | Key Strength | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMERALD-ID | Cryo-EM ligand identification | 44% exact identification, 66% closely related [21] | Moderate resolution cryo-EM (~3-4Å) | Combines physical forcefield with density agreement | Medium-High |

| LigPCDS Deep Learning | 3D point cloud segmentation | 67.2% top-10 accuracy, 93.6% top-10 recovery [6] | X-ray crystallography | Chemical structure recovery from density | High (GPU required) |

| DiffDock | Deep learning docking | State-of-the-art on PDBBind benchmark [30] | Not resolution-dependent | Blind docking capability | Medium |

| FLEXR-MSA | Electron density comparison | Qualitative improvement in detecting alternative conformations [31] | Medium-high resolution X-ray (<2.5Å) | Identifies hidden differences in sequence-diverse proteins | Medium |

| METEOR | Difference map denoising | Enables detection of previously unresolvable low-occupancy states [32] | Time-resolved crystallography | Reveals low-occupancy populations (<30%) | Low-Medium |

Specialized Capabilities Comparison

Different methodological approaches exhibit distinct strengths depending on the biological context and data quality. The specialized capabilities of each approach highlight their complementary nature in structural biology workflows.

Table 3: Specialized Capabilities Across Method Types

| Method Category | Low-Occupancy Ligand Detection | Handling Protein Flexibility | Sequence-Diverse Comparison | Cryo-EM Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Density Analysis | Limited (<0.5 occupancy) | Limited to rigid body | Not supported | Limited |

| Automated Model Building | Moderate (0.3-0.5 occupancy) | Side-chain flexibility only | Not supported | Limited |

| Iterative Denoising | Excellent (<0.3 occupancy) [32] | Limited | Not supported | Potential application |

| Deep Learning Docking | Not applicable | Excellent (full flexible docking) [30] | Indirectly through training data | Emerging |

| Cross-Map Comparison | Moderate | Captures conformational landscapes | Excellent (primary purpose) [31] | Not supported |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Difference Map Analysis for Low-Occupancy Ligands

The METEOR workflow exemplifies modern approaches to detecting low-occupancy species through optimized difference map calculation [32] [33]. The protocol begins with collection of paired crystallographic datasets—native and derivative—ensuring isomorphism with a maximum recommended RMSD of 0.3 Å for unit cell parameters. Researchers calculate difference structure factors (ΔF = F' - F) and apply negentropy-based weighting to maximize non-Gaussian signal in the resulting map. The core innovation involves total variation denoising, implemented with a regularization parameter optimized by maximizing map negentropy, defined as J(pρ) = H(pgauss) - H(pρ), where H represents differential entropy and pρ is the distribution of map voxel values [32]. This denoising step preserves sharp features while suppressing noise, typically improving signal-to-noise ratio by 30-50% for weak signals. The protocol concludes with phase extrapolation to calculate coefficients for the pure perturbed state, enabling modeling of low-occupancy ligands previously obscured by noise.

Cross-Protein Electron Density Comparison

FLEXR-MSA addresses the challenge of comparing electron densities across proteins with divergent sequences [31]. The methodology begins with multiple sequence alignment of target proteins using standard tools such as Clustal Omega or MAFFT. The aligned sequences guide the mapping of equivalent residues despite different numbering schemes. For each structure, electron density sampling occurs around each residue using five rotameric scans at 10° intervals (0°-360°). The tool calculates electron density values using either 2Fo-Fc or Fo-Fc maps, with sampling focused on the Cβ-Cγ bond for most amino acids. Density comparisons utilize Pearson correlation coefficients between equivalent positions in the sequence alignment, with statistical significance assessed through permutation testing. The output includes visualizations that chart alternative conformations across the protein surface, revealing global changes in conformational landscapes between isoforms or homologs. This approach has proven particularly valuable for studying proteins like HSP90 isoforms, where subtle conformational differences have implications for selective inhibitor design [31].

Cryo-EM Ligand Identification Workflow

EMERALD-ID addresses the growing use of cryo-EM in drug discovery by providing a robust protocol for ligand identification [21]. The process initiates with preparation of a candidate ligand library in SMILES format, which is converted to 3D conformers using tools like Open Babel. The cryo-EM density map and receptor model serve as input, with local resolution estimates informing the docking strategy. The method employs the RosettaGenFF small molecule force field for conformational sampling, generating multiple pose hypotheses for each candidate ligand. Each pose is evaluated using a composite scoring function that combines density correlation (CC) with estimated binding affinity (ΔG). To ensure fair comparison between different-sized ligands, the method applies a linear regression model that normalizes expected density correlation based on ligand size and local map resolution. The final output ranks candidate ligands by a composite score, with the protocol achieving 44% exact identification and 66% close analog identification on benchmarked cryo-EM structures [21].

Successful implementation of ligand validation workflows requires careful selection of computational tools and data resources. The following table catalogs essential components of the modern structural biologist's toolkit for ligand fitting applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Ligand Fitting and Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBbind | Curated dataset | Provides protein-ligand structures with binding affinity data | Method training and benchmarking [7] |

| HiQBind-WF | Data processing workflow | Creates high-quality protein-ligand datasets by fixing structural artifacts | Data preparation for analysis [7] |

| LigPCDS | Labeled dataset | 3D point cloud representations of ligands from crystallographic data | Deep learning model training [6] |

| CCD (Chemical Component Dictionary) | Reference database | Standardized chemical descriptions of small molecules | Ligand identity verification [7] |

| RosettaGenFF | Force field | Physical energy function for small molecule conformations | Ligand docking and scoring [21] |

| ESM-2 | Pre-trained model | Protein sequence representation learning | Feature extraction for docking [34] |

The methodological landscape for ligand validation in electron density maps has evolved from rigid docking approaches to sophisticated systems that account for protein flexibility, low-occupancy states, and evolutionary diversity. Traditional methods including difference map analysis and automated model building remain essential for standard crystallographic applications, while iterative denoising approaches like METEOR extend the detectable range to previously inaccessible low-occupancy ligands. Emerging deep learning methods show remarkable performance in flexible docking scenarios but face generalization challenges beyond their training data. Cross-comparison tools such as FLEXR-MSA offer unique capabilities for extracting functional insights from structural variations across protein families. The optimal choice of methodology depends critically on data type, resolution, biological question, and available computational resources. As structural biology continues to push toward more dynamic and complex systems, the integration of these complementary approaches will be essential for fully leveraging structural data in drug discovery applications.

The accurate identification and validation of small-molecule ligands in electron density maps represents a critical challenge in structural biology with profound implications for structure-guided drug design. As noted in recent literature, "the correct identification of ligands is often a vital part of structure-guided drug design" [35]. However, this process remains notoriously susceptible to human bias, as crystallographers may unconsciously fit desired or expected ligands into electron density, sometimes leading to questionable assignments [35] [36]. This challenge is compounded by the fact that ligands are typically modeled manually by chemists or biologists analyzing 3D density maps—a process that is both time-consuming and prone to error, particularly for structures with low resolution or local disorder [35].

Within this context, feature-engineered machine learning tools like CheckMyBlob have emerged as valuable resources to mitigate cognitive bias and standardize ligand identification. Unlike later deep learning approaches that process raw density maps through end-to-end learning, feature-engineered methods rely on carefully designed numerical descriptors to characterize electron density "blobs" [36] [37]. These tools exemplify a significant transition in structural biology informatics, where machine learning supplements human expertise to improve objective interpretation of experimental data. This article examines CheckMyBlob's methodology, performance, and position within the evolving ecosystem of computational tools for ligand validation.

CheckMyBlob: Mechanism and Methodology

CheckMyBlob employs a sophisticated machine learning pipeline that transforms electron density features into ligand predictions. The system operates through a multi-stage process that begins with electron density analysis and culminates in machine learning classification [37].

Electron Density Pre-processing and Blob Detection

The initial phase involves identifying unmodeled fragments of electron density through automated blob detection:

- Input Processing: The system accepts structure files (PDB or mmCIF) and experimental data files (MTZ) containing structure factors [38] [37].

- Blob Identification: CheckMyBlob analyzes all positive electron density peaks within the Fo-Fc difference map, focusing on regions exceeding the 2.8σ isosurface threshold computed with a 0.2 Å grid [35] [37].

- Skeletonization and Merging: To address the challenge of fragmented density, the system detects local maxima and skeletonizes the electron density within each blob's isosurface. Adjacent blobs are combined if the distance between their local maxima or skeleton nodes is less than 2.15 Å [37].

- Polymer Overlap Removal: Any electron density fragments that overlap with the isosurface of already-modeled biopolymer atoms are systematically excised from the blob to focus exclusively on unmodeled regions [37].

Feature Engineering and Machine Learning

Following blob detection, CheckMyBlob employs carefully engineered feature extraction:

- Feature Extraction: Each electron density blob is characterized by 382 numerical descriptors, including Zernike moment invariants, bounding box volume, and features extracted at different contour levels of electron density [36].

- Feature Selection: Through recursive feature selection, this extensive descriptor set is reduced to the 60 most informative features for model training [36].

- Classifier Training: These features train multiple machine learning models, including k-nearest-neighbors, random forests, and gradient boosting machines, with a stacked combination of these methods delivering optimal performance [36]. The model is trained on nearly 700,000 quality-filtered ligand instances from the PDB, clustered into 219 ligand groups based on structural characteristics [35] [37].

The following diagram illustrates CheckMyBlob's workflow from data input to ligand prediction:

Performance Comparison: CheckMyBlob Versus Alternative Approaches

CheckMyBlob's performance must be evaluated against both traditional methods and emerging deep learning alternatives. The following table summarizes key performance metrics across different approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ligand Identification Methods

| Method | Approach Type | Top-1 Accuracy | Top-5 Accuracy | Top-10 Accuracy | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CheckMyBlob | Feature-engineered ML | 59-71% [36] [37] | 85.2% [36] | 91.3-95% [36] [37] | X-ray crystallography only [35] |

| Deep Learning PointCloud | End-to-end deep learning | Similar to existing ML methods [35] | Not specified | Improved over feature-engineered methods [35] | X-ray & cryo-EM [35] |

| Traditional Iterative Fitting | Iterative fitting of candidate ligands | Lower than ML approaches [35] | Not specified | Not specified | Limited to known candidate ligands [35] |

The performance data reveals CheckMyBlob's particular strength in suggesting plausible ligands, with the correct identification appearing in the top-10 suggestions over 90% of the time [36] [37]. This capability makes it particularly valuable for practical structural biology workflows, where researchers can efficiently evaluate a limited number of candidates rather than searching through entire chemical libraries.

Comparative Limitations and Strengths

Each methodological approach exhibits distinct advantages and limitations:

- CheckMyBlob's Domain Specialization: As a feature-engineered system, CheckMyBlob excels within its domain of X-ray crystallography but cannot be directly applied to cryo-EM density maps without retraining [35]. The developers note that "all the existing ligand prediction approaches are applicable only to X-ray structures" [35].

- Deep Learning Flexibility: Emerging deep learning approaches using 3D point cloud representations demonstrate "similar accuracy to existing machine learning methods for X-ray crystallography while also being applicable to cryoEM density maps" [35]. This represents a significant advantage for multi-modal structural biology.

- Interpretability Trade-offs: Feature-engineered systems like CheckMyBlob offer greater interpretability, as the 60 selected features provide biochemical insight into which electron density characteristics contribute to classification decisions. Deep learning approaches typically function as "black boxes" with limited insight into their decision-making processes [39].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

CheckMyBlob Training and Validation Protocol

The experimental methodology underpinning CheckMyBlob's development followed a rigorous validation pipeline:

- Data Curation: 957,855 ligand blobs were initially extracted from PDB structures downloaded as of January 2020. Stringent quality filters were applied, eliminating ligands with resolution > 4.0 Å, RSCC < 0.6, real space Zobs (RSZO) < 1.0, real space Zdiff (RSZD) ≥ 6.0, R factor > 0.3, or occupancy < 0.3 [35].

- Ligand Clustering: Surviving ligands were clustered into groups based on the number of atoms, number of rings, connectivity, chirality, and atomic numbers using RDKit and SMILES/InChI descriptors from the PDB [35].

- Model Validation: Cross-validation experiments assessed performance on 696,887 ligand instances, with additional testing on a separate set of 17,150 ligands gathered after initial training [37].

Performance Assessment Protocol

To ensure fair comparison across methods, standardized assessment metrics must be employed:

- Accuracy Metrics: Top-1, top-5, and top-10 accuracy measurements evaluate how frequently the correct ligand appears within the top suggestions [36] [37].

- Certainty Calibration: CheckMyBlob provides probability estimates with its predictions, and "predictions with higher certainty are in fact very probable, whereas predictions with lower certainty values have a higher chance of being incorrect" [37].

- Cross-Technique Application: When evaluating the deep learning approach, "experiments assessing model performance on 208,896 X-ray crystallography ligands show that the proposed approach has similar accuracy to existing methods while improving in terms of top-10 accuracy" [35].

Structural biologists have access to an expanding toolkit of computational resources for ligand validation. The following table details key solutions available to researchers:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| CheckMyBlob Web Server | Feature-engineered ML | Identifies and validates ligands in electron density | Web server [38] |

| ChimeraX | Molecular visualization | Interactive model building and visualization | Downloadable software [35] |

| Deep Learning Ligand Classification | Point cloud deep learning | Ligand identification in X-ray and cryo-EM maps | GitHub repository [35] |

| MIC (Metric Ion Classification) | Deep metric learning | Classifies ions and waters in crystal and cryo-EM structures | Open-source package [39] |

| RCSB PDB Ligand Quality Indicators | Quality assessment | Assesses ligand structure quality via composite scores | RCSB.org web portal [40] |

These tools collectively address complementary aspects of the ligand modeling pipeline, from initial identification to final quality assessment. CheckMyBlob serves specifically the ligand identification and validation phase, while tools like MIC specialize in ion/water classification [39], and the RCSB PDB ligand quality indicators provide post-deposition validation [40].

Feature-engineered machine learning tools like CheckMyBlob represent a crucial evolutionary stage in computational structural biology, effectively bridging fully manual ligand modeling and emerging end-to-end deep learning approaches. While deep learning methods demonstrate promising expansion into cryo-EM applications and potentially reduced feature engineering overhead, CheckMyBlob's robust performance within X-ray crystallography—particularly its >90% top-10 accuracy—ensures its continued utility in practical structural biology workflows [36] [37].

The comparative analysis presented here suggests that rather than being rendered obsolete by deep learning, feature-engineered tools like CheckMyBlob will likely maintain specialized roles in contexts where interpretability, speed, and reliability for common ligands are prioritized. As the field advances, the integration of both feature-engineered and deep learning approaches within unified structural biology workbenches promises to further enhance objective ligand validation, ultimately strengthening the foundation for structure-based drug design and functional annotation of biomolecular structures.

In structure-guided drug design, accurately identifying the small-molecule ligands bound to proteins is paramount for understanding function and developing new therapeutics. This process traditionally relies on the manual interpretation of experimental density maps obtained from X-ray crystallography or cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM). However, this interpretation is notoriously challenging and susceptible to human bias, sometimes leading to the incorrect modeling of fictitious compounds [35]. The need for automated, accurate, and objective solutions has never been greater.

While automatic ligand identification methods have existed for X-ray crystallography, they have been largely based on iterative fitting procedures or feature-engineered machine learning, requiring significant manual input and computational time. Furthermore, these existing methods have not been applicable to the growing number of structures determined by cryo-EM [35]. A paradigm shift is underway with the advent of deep learning approaches that treat continuous 3D density maps as discrete 3D point clouds. This end-to-end deep learning framework offers a unified solution for ligand identification across both experimental modalities, demonstrating performance on par with established methods for X-ray data while extending critical capabilities to the cryo-EM field [35] [6].

The Point Cloud Paradigm: From Density Maps to Structural Insights

Fundamental Concepts and Workflow

A 3D point cloud is a dataset representing points in three-dimensional space, typically defined by (x, y, z) coordinates and often augmented with additional features like electron density value or chemical properties. This representation is particularly well-suited for processing by geometric deep learning architectures. The transformation of an experimental density map into a labeled ligand structure involves a multi-step workflow, as illustrated below.

The initial and crucial step involves blob extraction, where the ligand's density is isolated from the map. For X-ray data, this is typically done from the difference electron density map (Fo-Fc map), thresholded at a specific sigma level (e.g., 2.8σ) [35] [6]. The resulting density cluster, or "blob," is then sampled into a 3D point cloud. This point cloud can be processed directly by neural networks to identify the ligand or to perform a semantic segmentation task, where each point in the cloud is assigned a chemical label, effectively building the ligand's atomic structure [6].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and datasets that form the foundational "reagent solutions" for this field.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Point Cloud-Based Ligand Identification

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigPCDS | Dataset | A large-scale, chemically labeled dataset of 3D point clouds of protein ligands derived from X-ray crystallography for training and validation [6]. | Zenodo / Public Datasets |

| CheckMyBlob | Algorithm & Server | A benchmark machine learning method for ligand identification in X-ray maps; used for performance comparison [35]. | Web Server |

| ChimeraX Bundle | Software Plugin | An accompanying tool for the point cloud model, facilitating user-friendly application within a popular structural biology software suite [35]. | GitHub |

| Gemmi | Software Library | A library used for reading crystallographic data and creating 3D point cloud representations of ligands from density maps [6]. | Open Source |

| RDKit | Software Library | Used for cheminformatics tasks, such as clustering ligands into chemically meaningful groups based on descriptors like SMILES and InChI [35]. | Open Source |

Performance Comparison: Point Cloud Models vs. Established Methods

Quantitative Benchmarking on X-ray and Cryo-EM Data

The performance of the deep learning point cloud approach has been rigorously tested against established methods like CheckMyBlob. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from these evaluations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ligand Identification Methods

| Method | Principle | Application Scope | Reported Performance (X-ray) | Reported Performance (cryo-EM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Cloud Deep Learning [35] | End-to-end deep learning on 3D point clouds. | X-ray & cryo-EM density maps. | Similar accuracy to CheckMyBlob, with improved top-10 accuracy on 208,896 ligands. | Successful application to 34,671 cryoEM ligands, demonstrating transferability from X-ray training data. |

| CheckMyBlob [35] | Feature-engineered machine learning. | X-ray crystallography only. | Baseline accuracy for comparison. | Not applicable. |

| Iterative Fitting [35] | Trial fitting of candidate ligands. | X-ray crystallography only. | Slower, as requires fitting all candidate ligands. | Not applicable. |

| Semantic Segmentation on Point Clouds [6] | Pointwise labeling of 3D clouds to build chemical structures. | X-ray crystallography (primarily for structure building). | mIoU: 49.7% to 77.4%; F1-score: 62.4% to 87.0% on a stratified dataset (n=78,902). | Not reported. |

The point cloud method achieves comparable accuracy to the state-of-the-art CheckMyBlob for X-ray data but with a significant advantage: it is not limited to a single experimental technique. By training on electron density maps from X-ray crystallography, the model can be directly applied to Coulomb potential maps from cryo-EM, a crucial breakthrough for the field [35]. Experiments on a set of 34,671 cryo-EM ligands confirmed this capability, though the study also highlighted ongoing challenges with standardizing cryo-EM map processing [35].

Architectural Advantages and Limitations

The superior performance of point cloud models stems from several key architectural advantages. They inherently possess translation and rotation invariance, meaning their predictions are not affected by how the ligand is positioned or oriented within the map, a critical feature for robust real-world application [35] [41]. Furthermore, the end-to-end learning paradigm eliminates the need for manual feature engineering, allowing the model to learn the most relevant features directly from the data [35].

Despite these strengths, current limitations exist. The performance on cryo-EM data is contingent upon the quality and standardization of the map processing, which remains a challenge [35]. Moreover, like other data-driven methods, the model's accuracy is dependent on the breadth and quality of its training data, and identifying truly novel ligands (unknown unknowns) remains a complex task [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Curation and Point Cloud Generation

A critical factor in the success of deep learning models is the creation of high-quality, large-scale datasets. For ligand identification, this involves several standardized steps:

- Data Sourcing and Filtering: Structures are downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and filtered based on quality metrics. Common filters include removing structures with resolution worse than 4.0 Å, low real-space correlation coefficient (RSCC), or low ligand occupancy [35] [6].

- Map Calculation and Blob Extraction: For each structure, a difference electron density map (Fo-Fc) is calculated. Ligand "blobs" are extracted by isolating positive density peaks within an isosurface (e.g., 2.8σ) centered on the ligand's atomic coordinates [35] [6].

- Point Cloud Sampling: The density blob is converted into a 3D point cloud. Using tools like Gemmi, the blob is sampled onto a 3D grid with a defined spacing (e.g., 0.2 Å). Each point contains its 3D coordinates and a feature, typically the electron density value at that location [6].

- Chemical Labeling: For semantic segmentation tasks, the point cloud is labeled pointwise. This is often done using atomic sphere modeling, where points within the van der Waals radius of an atom are assigned a label based on a predefined chemical vocabulary (e.g., atom type, membership in an aromatic ring) [6].

Model Architecture and Training

The core innovation lies in the application of neural network architectures designed for 3D point clouds.

As shown in the diagram, the model core often employs rotation-invariant pointnets (e.g., RiConv) to process the point cloud. These layers ensure the model's predictions are not affected by the initial orientation of the ligand in the map, a fundamental requirement for robustness [35]. The network learns to aggregate spatial features from the points and their neighborhoods. The final layers, or "heads," are task-specific: a classification head outputs the identity of the ligand, while a segmentation head assigns a chemical label to each point, effectively building the ligand's structure atom-by-atom [6]. Models are typically trained on hundreds of thousands of ligand instances using standard deep learning optimizers, with a portion of the data held out for validation [35] [6].

The treatment of density maps as 3D point clouds for end-to-end deep learning represents a significant breakthrough in computational structural biology. This paradigm offers a powerful, unified approach for ligand identification that bridges the gap between X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM. By matching the performance of established methods for X-ray data while extending their capabilities to cryo-EM, this technology directly addresses the core thesis of validating ligand binding in electron density maps, reducing reliance on error-prone manual interpretation.

The future of this field is bright and points toward greater integration. Promising directions include the incorporation of quantum chemical properties like electron density directly into binding affinity predictions, offering a more fundamental understanding of interaction patterns [42]. Furthermore, the synergy between protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold and experimental density data is poised to enhance the accuracy and scope of model building, particularly for challenging regions [43] [44]. As these deep learning models mature and become more accessible through user-friendly software integrations, they are set to become an indispensable tool in the arsenal of researchers and drug developers, accelerating the pace of structural biology and drug discovery.

The integration of artificial intelligence-based structure prediction tools into visualization software has revolutionized structural biology, particularly in the validation of ligand binding in electron density maps. UCSF ChimeraX serves as a powerful hub for these tools, allowing researchers to seamlessly transition from prediction to analysis within a single environment. This capability is crucial for drug development professionals who require robust methods to verify ligand-protein interactions and avoid the cognitive biases that can lead to modeling fictitious compounds [45]. The extensible nature of ChimeraX through its "Toolshed" mechanism enables researchers to install specialized bundles that enhance its core functionality, creating customized workflows for specific research needs such as ligand validation [46].

The emergence of tools like AlphaFold, Boltz, and specialized deep learning bundles has transformed how researchers approach structure-guided drug design. These tools provide complementary capabilities—from predicting large protein complexes to estimating small molecule binding affinities—that together form a comprehensive toolkit for experimental validation. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics, integration pathways, and practical applications of these prediction technologies within ChimeraX workflows, with special emphasis on their utility for ligand binding validation in cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography research.

Comparison of Major Prediction Tools in ChimeraX

ChimeraX integrates multiple structure prediction engines that cater to different research scenarios and computational constraints. The table below summarizes the core tools available for structure prediction within the ChimeraX ecosystem.

Table 1: Core Structure Prediction Tools Available in ChimeraX

| Tool | Developer | Prediction Capabilities | Ligand Support | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold | Google DeepMind | Proteins, multimers | Limited (few dozen common ligands via server) | Non-commercial [47] |

| Boltz | MIT/Recursion Pharmaceuticals | Proteins, nucleic acids, modified residues, ligands, ions, solvent | Extensive (arbitrary ligands via CCD codes/SMILES) | Permissive MIT license [48] |

| ColabFold | Academic consortium | Optimized AlphaFold via Google Colab | Similar to AlphaFold | Non-commercial [49] |

| Ligand Recognizer | Karolczak et al. | Ligand identification in density maps | Specialized for ligand identification | Available on GitHub [45] |

Each tool occupies a distinct niche in the research workflow. AlphaFold excels at predicting protein structures and complexes but offers limited ligand support. Boltz provides comprehensive ligand handling capabilities but with more restrictive size limitations. The Ligand Recognizer bundle specializes specifically in identifying ligands within experimental density maps using deep learning, treating density maps as 3D point clouds for classification [45].

Performance Metrics and System Requirements

The practical utility of prediction tools depends heavily on their computational demands and performance characteristics. The following table compares key performance metrics across different hardware configurations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Boltz Predictions Across Hardware Platforms (Times in Minutes) [48]

| Assembly (PDB Code) | Tokens | Mac M1 16GB | Mac M1 Max 32GB | Linux Nvidia 4090 | Windows Nvidia 3070 | Intel CPU Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (8rf4) | 129 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.1-2.0 |

| Medium (1hho) | 382 | Fail | 1.5 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 8.0-11 |

| Large (9b3h) | 911 | Fail | 10 | 1.1 | 28 | 60-80 |

| Very Large (9gh4) | 1467 | - | 32 | 2.1 | - | 188 |

Tokens represent the number of standard polymer residues plus ligand atoms [48]. Several key observations emerge from this data: GPUs provide significant speed advantages, with high-end Nvidia GPUs performing predictions 10-30x faster than CPU-only configurations [48]. Memory limitations substantially constrain prediction capabilities on personal computers, particularly for larger complexes. The performance characteristics directly influence which tool is appropriate for a given research scenario.

AlphaFold server can handle much larger complexes (up to 5000 residues) but imposes different limitations—it only allows few dozen common ligands and prohibits commercial use [47]. For ligand-focused research, Boltz provides more flexible small-molecule support but with stricter size limitations, creating a practical trade-off that researchers must navigate based on their specific complex size and ligand requirements.

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Integration

Protocol for Ligand Binding Validation Using Multiple Tools

Validating ligand binding requires integrating multiple prediction and analysis tools in a systematic workflow. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach: