Validation of Anterior Nasal Swabs for Influenza Detection: Performance, Protocols, and Future Directions

This comprehensive review examines the validation of anterior nasal swabs as an alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs for influenza detection.

Validation of Anterior Nasal Swabs for Influenza Detection: Performance, Protocols, and Future Directions

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the validation of anterior nasal swabs as an alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs for influenza detection. Covering foundational principles, methodological approaches, performance optimization, and comparative validation, we analyze recent clinical studies demonstrating variable sensitivity (67-98%) across different collection techniques and populations. For researchers and drug development professionals, we detail technical specifications, sample processing protocols, and troubleshooting strategies to address suboptimal test characteristics. Evidence suggests anterior nasal sampling offers practical advantages for home testing and pediatric applications while maintaining robust performance for RSV detection, though influenza sensitivity requires further optimization through combined sampling approaches and technical refinements.

The Scientific Rationale for Anterior Nasal Sampling in Influenza Detection

For decades, the nasopharyngeal (NP) swab has been considered the gold standard for respiratory virus detection due to its high sensitivity, particularly for pathogens like influenza and SARS-CoV-2. This specimen type accesses the nasopharynx, where respiratory viruses replicate to high titers, theoretically providing optimal specimens for molecular detection [1]. However, this diagnostic standard presents significant limitations that hinder widespread testing implementation. NP swab collection is an invasive procedure that requires specialized training for healthcare personnel, creates patient discomfort that may reduce testing compliance, and consumes precious personal protective equipment (PPE) during collection [2] [3]. These limitations have prompted rigorous scientific evaluation of less invasive alternatives, particularly anterior nasal (AN) swabs, which can be self-collected by patients and are generally better tolerated. This review synthesizes current evidence comparing these sampling methods, focusing on analytical performance, practical implementation, and implications for influenza detection research and diagnostic development.

Comparative Performance: Nasopharyngeal versus Anterior Nasal Swabs

Detection Sensitivity Across Respiratory Viruses

Multiple studies have directly compared the sensitivity of NP and AN swabs for detecting various respiratory viruses. The evidence demonstrates that while NP swabs generally maintain slightly higher sensitivity, AN swabs provide clinically acceptable performance for most common pathogens, particularly when tested with highly sensitive molecular methods like RT-PCR.

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of AN Swabs Versus NP Swabs for Respiratory Virus Detection

| Virus | AN Swab Sensitivity | Testing Method | Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza | 89% (95% CI, 78%-99%) | rRT-PCR | Adults | [1] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 82%-88% | RT-PCR (Composite Reference) | Ambulatory Patients | [4] |

| Multiple Respiratory Viruses* | 84.3% (overall) | Multiplex Molecular Testing | Pediatric | [5] |

| Seasonal Coronavirus | 36.4% | Multiplex Molecular Testing | Pediatric | [5] |

| Adenovirus, Influenza, Parainfluenza, RSV, SARS-CoV-2 | 100% (when collected within 24h of NP) | Multiplex Molecular Testing | Pediatric | [5] |

*Includes adenovirus, seasonal coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, RSV, influenza, rhinovirus/enterovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and parainfluenza

The variation in sensitivity highlights several important patterns. First, performance differs significantly by virus type, with seasonal coronavirus showing notably poor detection in AN specimens [5]. Second, timing of specimen collection proves crucial, with sensitivity reaching 95.7% when AN swabs were collected within 24 hours of NP specimens in pediatric populations [6]. Third, the analytical sensitivity of the testing method influences comparative performance, with highly sensitive molecular methods like rRT-PCR demonstrating smaller differences between specimen types [1].

Impact of Viral Load on Detection Concordance

The concordance between NP and AN swabs is strongly influenced by viral load, as measured by cycle threshold (Ct) values in PCR assays. One systematic investigation found high concordance (Cohen's kappa >0.8) only for patients with viral loads above 1,000 copies/mL, while those with viral loads below this threshold exhibited low concordance (kappa = 0.49) [7]. This relationship explains why some studies report excellent agreement between methods while others find significant discrepancies. The majority of discordant results occur in patients with lower viral loads, where AN sampling may miss infections that NP swabs detect [7]. This has particular implications for testing later in the disease course or in asymptomatic individuals, who typically have lower viral loads.

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

Standardized Paired Sampling Methodology

Robust comparison of NP and AN swabs requires carefully controlled paired sampling protocols. The following methodology, adapted from multiple studies, provides a framework for valid comparison:

Participant Recruitment and Eligibility:

- Enroll patients presenting with symptoms of acute respiratory illness (<10 days duration) including fever, chills, or cough [1]

- Obtain informed consent and document symptom onset, vaccination status, and demographic information

- Exclude patients with thrombocytopenia (<50,000 platelets/μl) or nasal anatomy abnormalities [7]

Specimen Collection Sequence:

- AN Swab Collection: Insert a large-tipped, plastic-shafted Dacron swab approximately 1 centimeter into the nostril, rubbing along the nasal septum for 3-5 seconds while rotating [1]. Repeat in the other nostril with the same swab.

- NP Swab Collection: Using a wire-shafted Dacron swab, insert through the nostril approximately half the distance from the nares to the base of the ear (approximately 2 inches) until resistance is met [1]. Rotate the swab gently and withdraw.

Note: Always collect the less invasive AN specimen first to maximize recovery of material from both sites and minimize potential contamination from NP sampling [7].

Specimen Handling and Transport:

- Place swabs immediately into appropriate transport media (M4-RT viral transport media, Universal Transport Medium, or specific manufacturer-recommended media) [1] [8]

- Refrigerate specimens at 4°C for <24 hours until processing

- Aliquot and freeze at -70°C for long-term storage if not tested immediately [9]

Testing Methodology:

- Test all specimens using the same analytical platform and batch to minimize inter-assay variability

- Utilize highly sensitive molecular methods (rRT-PCR) with validated limits of detection [1]

- Include appropriate controls (human nucleic acid extraction control, amplification controls) [1]

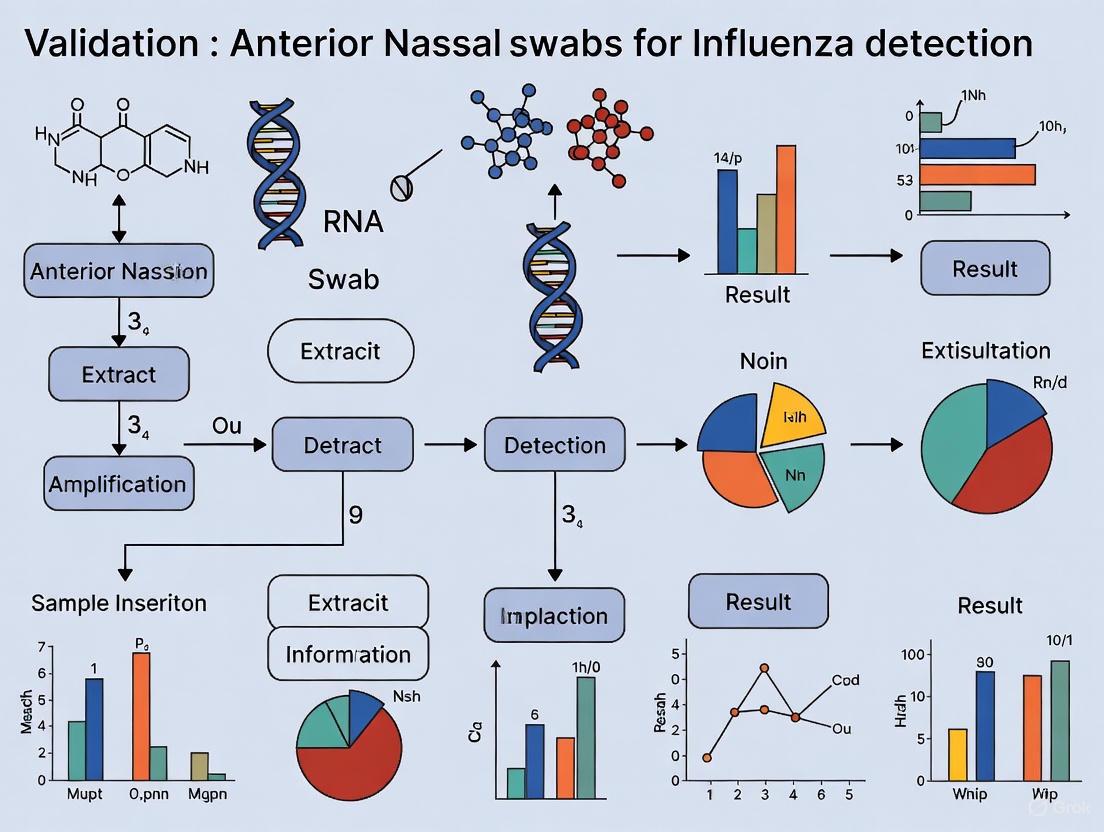

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for comparative studies of nasal sampling methods:

Special Considerations for Pediatric Populations

Sampling children requires specific adaptations to ensure both comfort and diagnostic accuracy:

- Allow for collection by caregivers with appropriate instruction and observation by healthcare personnel [9]

- Use visual aids or demonstrations to reduce anxiety

- Evaluate tolerability using standardized scales (1=pleasant to 5=unpleasant) completed by both children (when age-appropriate) and caregivers [9]

- Consider shorter swab insertion times while maintaining adequate sampling duration for quality specimens

Recent pediatric studies demonstrate that AN swabs achieve 95.7% sensitivity when collected within 24 hours of NP specimens, highlighting their utility in this population [6].

Complications and Safety Profile Comparison

Adverse Events Associated with NP Swabs

While generally safe when performed by trained personnel, NP swab collection carries a risk of complications ranging from minor discomfort to serious adverse events:

Table 2: Documented Complications of Nasopharyngeal Swabbing

| Complication Type | Frequency | Risk Factors | Management | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epistaxis | 0.0012%-0.026% | Coagulopathy, nasal anatomy | Nasal packing, cauterization | [2] |

| Retained Swab | Rare | Structural abnormalities, technique error | Endoscopic removal | [2] |

| CSF Leak | Very rare | Skull base defects, prior surgery | Surgical repair | [2] |

| Nasal Septal Abscess | Case reports | Pre-existing nasal conditions | Surgical drainage, antibiotics | [2] |

The overall complication rate requiring medical evaluation ranges from 0.0012% to 0.026% [2]. However, these statistics likely underestimate minor adverse events and discomfort that go unreported but impact patient experience and testing compliance.

Safety Advantages of AN Swabs

AN swabs offer a substantially improved safety profile due to their minimal intrusion and avoidance of sensitive nasal structures:

- No risk of cribriform plate injury or cerebrospinal fluid leakage due to shallow insertion depth [2]

- Minimal epistaxis risk as swabs do not contact the highly vascularized nasopharynx

- Eliminated risk of swab fracture in deep nasal structures as mechanical stress is reduced

- Suitable for self-collection with proper instruction, reducing healthcare worker exposure [3]

Proper AN swab technique involves inserting the swab only ½ to ¾ of an inch into the nose and performing at least four sweeping circles against the anterior nares wall with moderate pressure in each nostril [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Comparative Swab Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| NP Swabs | Wire-shafted, Dacron/rayon tip, length ~6 inches | Access nasopharyngeal region | Remel Aluminum/Plastic Unishaft Swab [1] |

| AN Swabs | Plastic-shafted, larger Dacron tip, standard length | Sample anterior nares region | Copan Nylon-Flocked Dry Swab [9] |

| Transport Media | Viral transport media (VTM), Universal Transport Media | Preserve viral integrity during transport | M4-RT Media, UTM (Copan) [1] [8] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Silica-membrane or magnetic bead technology | Isolate viral RNA/DNA | QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT Kit [8] |

| PCR Master Mixes | One-step RT-PCR chemistry, compatible with platform | Amplify viral targets | Invitrogen SuperScript III Platinum One-Step [1] |

| Positive Controls | Inactivated virus or synthetic RNA transcripts | Verify assay performance | Quantified specific in vitro-transcribed RNA [8] |

Implications for Influenza Detection Research

The validation of AN swabs for respiratory virus detection has significant implications for influenza research and public health surveillance:

Expanding Testing Accessibility and Compliance

The less invasive nature of AN swabs enables testing scenarios not feasible with NP swabs:

- Self-collection programs allow broader community surveillance and earlier case detection

- Home-based testing facilitates rapid initiation of antiviral therapy when most effective

- Pediatric and geriatric populations experience reduced testing barriers, improving enrollment in clinical studies

- Resource-limited settings can implement testing without specialized healthcare personnel

Considerations for Research Design

When incorporating AN swabs into influenza research protocols, several factors require attention:

- Viral load dynamics throughout infection course may affect AN swab sensitivity differently than NP

- Specimen storage conditions and stability may differ between sample types

- Automated processing systems may require validation with AN specimen formats

- Self-collection instruction quality significantly impacts specimen adequacy [3]

Recent technological advances have further improved AN swab utility, with some antigen tests demonstrating equivalent diagnostic accuracy between AN and NP swabs, though sometimes with lower test line intensity that could affect interpretation by untrained users [8].

Evidence from multiple comparative studies supports AN swabs as a clinically acceptable alternative to traditional NP swabs for influenza detection and respiratory virus surveillance. While NP swabs maintain marginally higher sensitivity for some pathogens, particularly at low viral loads, the advantages of AN swabs—including reduced patient discomfort, elimination of specialized healthcare personnel for collection, minimal complication risk, and self-collection capability—position them as a transformative tool for scaling respiratory virus testing. Future research should focus on optimizing collection techniques, particularly for self-collection scenarios, and developing even less intrusive detection methods that maintain diagnostic accuracy across the spectrum of respiratory pathogens.

Pandemic-Driven Innovation in Respiratory Virus Testing Methodologies

The COVID-19 pandemic created unprecedented global demand for accessible, scalable, and comfortable respiratory virus testing, catalyzing a significant shift in diagnostic methodologies. This comparison guide examines the validation of anterior nasal swabs as a viable alternative to traditional nasopharyngeal sampling across multiple respiratory pathogens, with particular focus on influenza detection. We present comprehensive experimental data from recent clinical studies evaluating sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation across diverse patient populations and testing platforms. The evidence demonstrates that anterior nasal swabs offer a favorable balance of patient comfort and diagnostic accuracy while enabling self-collection capabilities—advancements that have profound implications for future pandemic preparedness and respiratory virus surveillance.

Respiratory virus diagnostics historically relied on nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs as the gold standard specimen type due to their high viral load recovery [10] [4]. However, the pandemic exposed critical limitations of NP swabs: they require trained healthcare personnel, cause patient discomfort, and pose infection risks to collectors due to sneeze and cough induction [11]. These challenges triggered accelerated innovation toward less invasive methods, particularly anterior nasal swabs, which can be self-collected with minimal training [5].

The validation of anterior nasal swabs represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic approaches, balancing analytical sensitivity with practical implementation needs. This guide systematically compares the performance characteristics of anterior nasal swabs against established methodologies across multiple respiratory viruses, with detailed experimental protocols and performance metrics to inform researchers and clinical laboratory professionals.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Diagnostic performance of anterior nasal swabs compared to nasopharyngeal swabs

| Virus | Testing Method | Anterior Nasal Sensitivity | NP Swab Sensitivity | Specificity | Study Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza | rRT-PCR | 89% (95% CI, 78%-99%) | 94% (95% CI, 87%-100%) | Not reported | 240 adults [1] |

| Influenza | Rapid Antigen | 67% (95% CI, 49%-81%) | Reference | 96% (95% CI, 89%-99%) | 128 emergency department patients [12] |

| RSV | Rapid Antigen | 75% (95% CI, 43%-95%) | Reference | 99% (95% CI, 93%-100%) | 128 emergency department patients [12] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | RT-PCR | 82%-88% (Composite) | 98% (Composite) | >97% | Meta-analysis of ambulatory patients [4] |

| Multiple Respiratory Viruses* | Multiplex PCR | 84.3% (Overall) | Reference | 100% (Multiple viruses) | 147 pediatric patients [5] |

*Includes adenovirus, seasonal coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, RSV, influenza, rhinovirus/enterovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and parainfluenza

Impact of Timing and Viral Load

Table 2: Factors influencing anterior nasal swab sensitivity

| Factor | Impact on Sensitivity | Study Details |

|---|---|---|

| Time from NP collection | 95.7% when collected within 24h vs 84.3% overall | Pediatric study, 147 pairs [5] |

| Viral Load (Ct value) | Significantly higher sensitivity with lower Ct values (higher viral loads) | Mean Ct 25.5 vs 29.5 in detected vs missed samples [13] |

| Symptom Duration | Higher sensitivity in early symptomatic phase (1-5 days) | Median 2 days from symptom onset in optimal performance [11] |

| Virus Type | Variable by pathogen: 100% for adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, RSV, SARS-CoV-2; 36.4% for seasonal coronaviruses | Pediatric study within 24h of NP [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Anterior Nasal Collection Procedure

The following protocol represents a consensus methodology derived from multiple validation studies:

- Swab Selection: Use flocked swabs (e.g., FLOQSwabs) for optimal specimen collection and release [11]

- Insertion Depth: Insert swab approximately 1-2 cm into nostril (significantly shallower than NP insertion) [1] [11]

- Sampling Technique: Rotate swab gently along nasal septum for 3-5 seconds [1] [13]

- Dwell Time: Maintain swab position for 5 seconds to ensure adequate absorption [11]

- Processing: Place swab in appropriate transport media (e.g., Universal Transport Medium, M4-RT viral transport media) [1] [13]

Comparative Study Designs

Key validation studies employed rigorous methodological approaches:

Prospective Paired Design (Influenza Detection, 2012): 240 adult patients with acute respiratory illness provided paired nasal and NP swabs collected by trained personnel. Specimens were tested via both rRT-PCR and viral culture with a composite gold standard (any positive result from either specimen type). Statistical analysis included sensitivity calculations with 95% confidence intervals and chi-square comparisons [1].

Pediatric Validation (Multiple Viruses, 2025): 147 hospitalized children had anterior nasal swabs collected within 72 hours of NP specimens. Both specimen types were tested using multiplex molecular testing for 8 respiratory viruses. Concordance, sensitivity, and specificity were assessed with particular attention to timing between collections [5].

Self-Collection Validation (Influenza/RSV, 2025): Emergency department patients self-collected oral-nasal swabs (anterior nares, buccal mucosa, tongue) while healthcare providers collected NP swabs. Multiplex PCR testing compared performance characteristics, evaluating feasibility of self-collection [12].

Diagram Title: Validation Workflow for Anterior Nasal Swabs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for respiratory virus testing research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Flocked Swabs | Optimal specimen collection and release | FLOQSwabs (Copan Italia S.p.A.); Puritan Sterile Foam Tipped Applicators [11] [13] |

| Transport Media | Viral preservation during transport | Universal Transport Medium (UTM, Copan); M4-RT viral transport media (Remel) [1] [11] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | RNA purification for molecular testing | Maxwell HT Viral TNA Kit (Promega); magLEAD 6gC (Precision System Science) [10] [12] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Amplification of viral targets | Luna Universal Probe One-Step RT q-PCR kit (New England Biolabs); THUNDERBIRD Probe One-step qRT-PCR Kit (TOYOBO) [10] [12] |

| Automated Testing Platforms | High-throughput standardized testing | cobas 6800 (Roche); NeuMoDx (Qiagen); LightCycler Systems (Roche) [1] [10] |

| Reference Standards | Assay validation and quantification | EDX SARS-CoV-2 Standard (Bio-Rad); INSTAND e.V. quantitative reference samples [10] |

Discussion and Research Implications

Advantages and Limitations

The collective evidence demonstrates that anterior nasal swabs provide a favorable balance of patient comfort and diagnostic accuracy for most respiratory viruses. The significantly reduced discomfort and cough/sneeze induction [11] enable broader testing acceptance and self-collection capabilities. However, the moderately reduced sensitivity compared to NP swabs, particularly for influenza and seasonal coronaviruses, requires careful consideration in clinical and research applications [12] [5].

The strong dependence on viral load represents a critical factor in test performance. Studies consistently show superior detection when anterior nasal samples are collected early in symptomatic illness when viral loads are highest [11] [13]. This supports their application in community surveillance and early diagnosis scenarios but suggests limited utility in later disease stages or low-prevalence settings.

Future Research Directions

The pandemic-driven validation of anterior nasal swabs has established a new trajectory for respiratory virus diagnostics. Priority research areas include:

- Optimization of self-collection protocols for diverse populations including children, elderly, and immunocompromised patients

- Development of specialized transport media specifically formulated for anterior nasal specimens

- Standardization of sampling techniques across different swab types and collection devices

- Validation with emerging pathogen threats to establish preparedness for future pandemics

- Integration with point-of-care platforms to enable rapid diagnosis in non-clinical settings

The compelling evidence from multiple validation studies confirms that anterior nasal swabs represent a significant methodological advancement in respiratory virus testing. While nasopharyngeal swabs maintain slightly higher analytical sensitivity, the practical advantages of anterior nasal sampling—including patient comfort, reduced healthcare worker exposure, and self-collection capability—establish it as a viable alternative for most clinical and research applications.

The pandemic has accelerated the validation and adoption of this innovative methodology, creating new paradigms for respiratory virus surveillance that balance diagnostic accuracy with practical implementation. As research continues to refine collection techniques and expand applications, anterior nasal swabs are poised to become increasingly central to respiratory virus testing strategies in both routine clinical practice and pandemic preparedness.

Influenza viruses are significant human pathogens that cause seasonal epidemics and substantial respiratory morbidity. The replication sites of influenza viruses within the human host are fundamental to understanding disease pathogenesis and optimizing detection strategies. Both Influenza A (IAV) and Influenza B (IBV) viruses exhibit a strong tropism for the epithelial cells of the human respiratory tract. Following intranasal transmission, the viral replication cycle begins with the binding of viral hemagglutinin (HA) to sialic acid receptors on host respiratory epithelial cells, triggering receptor-mediated endocytosis [14] [15]. The viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) are subsequently released into the cytoplasm and transported to the nucleus, where genome replication and transcription occur—an unusual characteristic for an RNA virus that provides access to the host's nuclear machinery [16] [15]. Newly synthesized viral components are then assembled into progeny virions that bud from the host cell membrane, a process facilitated by the neuraminidase (NA) protein, which cleaves sialic acids to enable viral release [14] [15]. This entire replication process occurs within the cells lining the upper respiratory tract, making this anatomical region the primary source for viral shedding and the optimal target for clinical specimen collection.

Comparative Performance of Anterior Nasal and Nasopharyngeal Swabs

The accurate detection of influenza virus relies on collecting specimens from the sites of active viral replication. While the nasopharyngeal (NP) swab has traditionally been considered the "gold standard" due to its higher sensitivity, less invasive anterior nasal swabs (NS) offer practical advantages for widespread testing and patient self-collection. The performance of these swab types has been systematically evaluated in multiple clinical studies, with key quantitative comparisons summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Nasal and Nasopharyngeal Swabs for Influenza Detection

| Study and Swab Type Comparison | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midturbinate (MTS) vs. Nasopharyngeal (NPS) (2024, n=93 paired samples) | 92% (MTS) vs. 95% (NPS) | N/A | MTS yielded a 53% lower viral load; NPS provided significantly higher viral load (p=0.0002). | [17] |

| Anterior Nasal (NS) vs. Nasopharyngeal (NP) (2012, n=240 adults) | 89% (NS) vs. 94% (NP) by rRT-PCR | N/A | No statistically significant difference in sensitivity by rRT-PCR (p=0.40). | [1] |

| Residual Nasal Swab (rNS) vs. NP/OP (2023, n=199 paired specimens) | 81.3% | 96.7% | Feasible to use a single anterior nasal swab for rapid testing followed by RT-PCR confirmation. | [18] |

| Anterior Nasal (NS) vs. Nasopharyngeal (NP) (2025, n=147 children, multiple viruses) | 84.3% (Overall) | N/A | Sensitivity increased to 95.7% when NS was collected within 24 hours of NP swab. Sensitivity for influenza was 100% within this timeframe. | [19] |

The data reveals that while NP swabs generally yield higher viral loads and sensitivities, anterior nasal swabs perform with good to excellent sensitivity, particularly when highly sensitive molecular tests like rRT-PCR are used [1] [19]. The timing of collection is critical, with anterior nasal swabs showing maximal sensitivity when collected close to symptom onset or to a reference NP swab [19]. Furthermore, one study demonstrated that it is feasible to use a single anterior nasal swab for both rapid antigen testing and subsequent molecular confirmation via RT-PCR, streamlining the testing process [18].

Experimental Protocols for Swab Comparison

To generate the comparative data presented above, researchers have employed rigorous experimental methodologies. The following workflow visualizes the standard protocol for a paired swab comparison study, as implemented in recent clinical research.

Diagram 1: Paired Swab Study Workflow

Detailed Methodology

The core components of the experimental protocols from key cited studies are detailed below:

Patient Population and Specimen Collection: Studies typically enroll patients of all ages presenting with acute respiratory illness symptoms (e.g., cough, fever) of short duration (e.g., <48 hours to <7 days) [17] [1]. Per study protocols, a mid-turbinate or anterior nasal swab is collected from one nostril, immediately followed by a nasopharyngeal swab from the other nostril using specialized swabs (e.g., Copan FLOQSwabs) [17] [1]. The order of collection is important; the less invasive swab is often collected first to minimize discomfort and potential cross-contamination [1].

Specimen Handling and Storage: Collected swabs are placed into tubes containing universal transport medium (e.g., Copan UTM, Remel M4RT) [17] [1]. Specimens are stored under refrigerated conditions (2-8°C) and shipped to a central laboratory within a strict timeframe (e.g., within 36 hours of collection) [17]. Upon receipt, samples are aliquoted and stored at -80°C until batch testing to preserve viral RNA integrity [17] [18].

Laboratory Testing and Viral Load Quantification: Viral RNA is purified from the samples using automated systems like the MagNA Pure 96 (Roche) [17]. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) is performed using validated assays, such as the CDC Human Influenza Virus Real-time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, which targets conserved influenza genes (e.g., matrix protein M1 for influenza A, non-structural protein NS1 for influenza B) [17] [1]. The cycle threshold (Ct) values are recorded, and viral loads are calculated by comparison to a standard curve, often reported in log10 virus particles per milliliter (log10 vp/mL) [17]. Some studies also perform viral culture in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells as an additional detection method [1].

Data Analysis: The statistical analysis is exploratory and primarily descriptive. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests are used for paired comparisons of continuous variables (e.g., viral load), while McNemar's test is used for paired binary data (e.g., positive/negative results) [17]. Sensitivity and specificity are calculated using standard methods, sometimes employing a composite gold standard that considers any positive result from either specimen type by any test method [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table catalogues essential materials and reagents used in the cited influenza detection and swab comparison studies, providing researchers with a practical resource for experimental design.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Influenza Detection Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal Swabs | Copan FLOQSwabs 501CS01 (minitip nylon flocked) [17]; Aluminum/plastic unishaft swab (Remel) [1] | Collects specimen from the nasopharynx. Mini-tip and flexible shaft designed for patient comfort and effective collection. |

| Midturbinate/Anterior Nasal Swabs | Copan FLOQSwabs 56380CS01 (adult midturbinate nylon flocked) [17]; Puritan Sterile Foam Tipped Applicator [18] | Collects specimen from the mid-turbinate region or anterior nares. Less invasive than NP swabs. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Copan UTM [17]; Remel MicroTest M4RT [1] [18] | Preserves viral integrity during transport and storage from collection site to laboratory. |

| RNA Extraction System | MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche) [17] | Automated purification of viral RNA from clinical specimens for downstream molecular testing. |

| qRT-PCR Assays | Proprietary influenza matrix gene qRT-PCR [17]; CDC Human Influenza Virus Real-time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel [1] [18] | Quantitatively detects and differentiates influenza A and B virus RNA with high sensitivity and specificity. |

| Cell Culture System | Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells [1] | Supports the propagation of influenza virus for culture-based detection and research. |

The virological foundation of influenza replication is firmly rooted in the epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract. This tropism directly informs and validates the use of upper respiratory specimens for disease diagnosis. Robust comparative studies demonstrate that while nasopharyngeal swabs yield higher viral loads and remain the most sensitive option, anterior nasal swabs offer a statistically comparable and clinically useful alternative for influenza detection, especially when paired with highly sensitive molecular methods like qRT-PCR. The adoption of anterior nasal swabs, supported by standardized collection and testing protocols, can significantly ease large-scale influenza surveillance, enhance patient comfort, and facilitate broader testing strategies in both clinical and community settings.

The accurate detection of respiratory viruses is a cornerstone of public health and clinical management. For decades, the nasopharyngeal (NP) swab has been considered the gold standard for sample collection due to its high diagnostic yield. However, its collection is invasive, requires trained healthcare professionals, and can be uncomfortable for patients. In recent years, the anterior nasal (AN) swab has emerged as a less invasive, more patient-friendly alternative that is also suitable for self-collection. This guide provides an objective comparison of viral shedding patterns between these two anatomical sites, synthesizing current research to evaluate the performance of AN swabs within the broader context of validating their use for influenza and SARS-CoV-2 detection.

Quantitative Comparison of Diagnostic Performance

Extensive clinical studies have directly compared the sensitivity and specificity of NP and AN swabs for detecting respiratory viruses. The table below summarizes key findings from recent research.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Anterior Nasal vs. Nasopharyngeal Swabs

| Virus Target | Test Type | Sensitivity (AN vs. NP) | Specificity (AN vs. NP) | Key Findings & Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 [8] | Antigen (Ag-RDT - Sure-Status) | AN: 85.6%NP: 83.9% | AN: 99.2%NP: 98.8% | Diagnostic accuracy was equivalent. High agreement (κ=0.918). |

| SARS-CoV-2 [8] | Antigen (Ag-RDT - Biocredit) | AN: 79.5%NP: 81.2% | AN: 100%NP: 99.0% | Diagnostic accuracy was equivalent. High agreement (κ=0.833). |

| Influenza [20] | PCR (vs. HCW NP & Nasal) | AN: 78%(vs. HCW NP) | AN: 100%(vs. HCW NP) | Self-collected AN swabs in older adults. |

| Influenza A & B [13] | PCR | rNS*: 81.3% | rNS*: 96.7% | Single AN swab used for rapid test and PCR. |

| RSV [21] | PCR (Multiplex) | AN: 75% | AN: 99% | Self-collected oral-nasal swab in an emergency department. |

| Multiple (Pediatric) [9] | PCR (Multiplex Panel) | High agreement with NP for SARS-CoV-2, RSV, Influenza | High agreement with NP for SARS-CoV-2, RSV, Influenza | AN and saliva samples were better tolerated than NP in children. |

Table 1 Note: rNS = residual nasal swab (an anterior nasal swab used for a rapid test before being stored for PCR).

A critical finding across multiple studies is the strong correlation of viral load between the two sites. Research on SARS-CoV-2 outpatients found that AN and NP RNA levels were highly correlated (r=0.84), indicating that both compartments reflect similar shedding dynamics [22]. The limits of detection for SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests were also not significantly different between the two swab types [8].

Insights from Viral Shedding Kinetics

Understanding viral shedding—the release of viral particles from an infected host—is key to interpreting diagnostic results.

- Shedding Concordance: Viral shedding in the nasopharynx and anterior nares is highly concordant. Higher RNA levels in these upper respiratory tract compartments are associated with greater detection of virus in other compartments, such as oral wash/saliva and plasma [22].

- Predictors of Shedding: Certain host factors influence viral load. Older age has been consistently associated with higher nasopharyngeal RNA levels at diagnosis. Some studies also indicate that men may have slower viral clearance from the nasopharynx than women, which could contribute to sex-based differences in disease outcomes [22].

- Shedding and Infectiousness: It is crucial to distinguish between the detection of viral RNA (via PCR) and the presence of replication-competent infectious virus. While PCR is highly sensitive, it can detect viral fragments long after the infectious period has ended. The presence of infectious virus is best determined by virus isolation in cell culture, a complex method not suited for clinical diagnostics [23]. Antigen-detecting rapid tests (Ag-RDTs) often serve as a more practical proxy for infectiousness, as they typically become positive only during periods of high viral load [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

To facilitate the replication and critical appraisal of these findings, here are the methodologies from two pivotal studies cited in this guide.

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Protocols

| Study Component | Sure-Status/Biocredit Ag-RDT Evaluation [8] | Concordance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Levels [22] |

|---|---|---|

| Study Population | Symptomatic adults at a drive-through test center (Sure-Status: n=372; Biocredit: n=232). | Outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in the ACTIV-2/A5401 trial (n=537 for baseline). |

| Sample Collection | Healthcare worker-collected:1. NP swab (for reference RT-qPCR).2. NP swab (for Ag-RDT) from other nostril.3. AN swab (for Ag-RDT) from both nostrils. | Longitudinal collection:- Dry NP swab (healthcare worker-collected).- Dry AN swab (self-collected).- Oral wash/saliva and plasma. |

| Reference Standard | RT-qPCR (TaqPath COVID-19) on NP swab. | Quantitative SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing on all sample types. |

| Index Test | Two Ag-RDT brands (Sure-Status & Biocredit) run on paired AN and NP swabs. | Not applicable (observational comparison). |

| Analysis | Sensitivity, specificity, Cohen's kappa (κ), limit of detection (LoD). | Spearman's correlation, linear regression models for censored data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and reagents commonly used in this field of research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Flocked Swabs (e.g., Copan FLOQSwabs) | Sample collection from NP and AN sites. Designed to release collected material efficiently into transport media [13]. |

| Universal Transport Media (UTM) | Preserves viral integrity during transport and storage for subsequent PCR or culture [8]. |

| Viral RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate viral RNA from clinical specimens prior to RT-PCR (e.g., QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT kit) [8]. |

| RT-qPCR Assays | Quantitative detection of viral RNA (e.g., TaqPath COVID-19, CDC Human Influenza Virus RT-PCR Panel) [8]. |

| Cell Lines for Virus Isolation | Determine the presence of infectious virus (e.g., Vero E6, Caco-2, Calu-3 cells) [23]. |

| Ag-RDT Kits | Rapid, lateral flow immunochromatographic tests for detecting viral antigens at point-of-care [8]. |

Research Workflow and Logical Relationships

The diagram below outlines the typical workflow for a head-to-head comparative study of nasopharyngeal and anterior nasal swabs.

The collective evidence demonstrates that anterior nasal swabs are a valid and reliable alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs for detecting influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and other respiratory viruses. While some studies report a modest reduction in sensitivity for AN swabs, particularly for influenza, the overall diagnostic accuracy is largely equivalent, especially when viral loads are high [8] [21] [13]. The high correlation of viral RNA levels between the two sites further supports the use of AN swabs for monitoring viral shedding dynamics [22].

The advantages of AN swabs—enhanced patient comfort, feasibility for self-collection, and reduced need for professional training—present a compelling case for their adoption in both clinical and community settings [20] [9]. Future research should continue to optimize self-collection protocols and explore the impact of emerging viral variants on test performance across different anatomical sites.

Regulatory Landscape Evolution for Alternative Sampling Methods

The regulatory landscape for respiratory virus diagnostics is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by technological advances and a growing need for accessible testing options. Traditional nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) have long been the gold standard for specimen collection due to their high viral yield, but their invasive nature and requirement for healthcare professional administration present limitations for widespread use [24] [25]. The emergence of global respiratory pandemics has accelerated regulatory acceptance of less invasive alternative sampling methods, particularly anterior nasal swabs (ANS), which offer the advantage of potential self-collection and reduced patient discomfort [26] [27].

This evolution is particularly relevant for influenza detection, where timely diagnosis is critical for implementing effective treatment and containment strategies. The regulatory pathway for these alternatives requires robust clinical validation to establish diagnostic performance comparable to established methods. This guide objectively compares the performance of anterior nasal swabs against other sampling methods within the context of influenza detection research, providing researchers and developers with the experimental data and regulatory framework necessary to advance this field [28].

Performance Comparison of Respiratory Specimen Types

Extensive research has compared the diagnostic accuracy of various upper respiratory specimen types for detecting viral pathogens. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of Alternative Specimens vs. Nasopharyngeal Swabs

| Specimen Type | Target Pathogen | Sensitivity (%, vs. NPS) | Specificity (%, vs. NPS) | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Nasal Swab (ANS) | SARS-CoV-2 | 80.7% | 99.6% | Lower viral load (higher Ct) but suitable for outpatient setting [26]. |

| ANS (10 rubs) | SARS-CoV-2 | Comparable to NPS | N/A | Significantly better than 5-rub ANS (Ct 24.3 vs. 28.9); achieved similar concentration to NPS [24]. |

| Oral-Nasal Swab | Influenza | 67.0% | 96.0% | Suboptimal for Influenza; not an acceptable substitute for NPS [12]. |

| Oral-Nasal Swab | RSV | 75.0% | 99.0% | Performance characteristics preserved better for RSV than for Influenza [12]. |

| Nasal Swab (RAT) | SARS-CoV-2 | 81.0% | 100.0% | Achieved WHO sensitivity requirement (0.80); higher than NPS (0.75) in this context [29]. |

Table 2: Analysis of Specimen Collection Characteristics and Applications

| Characteristic | Nasopharyngeal (NPS) | Anterior Nares (ANS) | Oral-Nasal | Saliva |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Sensitivity | High (Reference) | Moderate to High | Moderate (Varies by pathogen) | Moderate |

| Patient Comfort | Low (Invasive) | High (Minimally invasive) | High | High |

| Collection Skill Required | High (Healthcare professional) | Low (Suitable for self-collection) | Low (Suitable for self-collection) | Low (Suitable for self-collection) |

| Key Advantages | Highest viral concentration; established standard | Patient-friendly; suitable for home testing | Combines oral and nasal surfaces; simple collection | Non-invasive |

| Primary Limitations | Discomfort, requires trained staff, PPE | Potentially lower viral load | Suboptimal for some pathogens (e.g., Influenza) | Variable viscosity, potential interference |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure the validity and reliability of data supporting regulatory submissions, researchers must employ rigorous experimental designs. The following protocols outline key methodologies used in recent studies evaluating alternative sampling methods.

Protocol for Paired-Sample Diagnostic Accuracy Study

This protocol, based on a study comparing ANS versus combined oro-/nasopharyngeal (OP/NP) sampling, highlights the direct comparison of a new method against a reference standard [26].

- Study Population and Setting: Recruit adult patients presenting to an emergency department or ambulatory clinic with symptoms suggestive of a respiratory viral infection (e.g., influenza). A sufficient sample size should be calculated for power and confidence intervals.

- Sample Collection: For each participant, collect the alternative specimen (e.g., ANS) first to avoid contamination of the nasal area by the NP procedure. Immediately afterward, a trained healthcare professional collects the reference standard NP swab.

- ANS Collection: Insert a flocked ANS (e.g., Rhinoswab) into both nostrils until resistance is met. Leave in place for 60 seconds, optionally with side-to-side movements for 15 seconds [26].

- NP Collection: Insert a flexible mini-tip flocked swab through the nostril to the nasopharynx. Rotate the swab several times against the posterior nasopharyngeal wall and hold for a few seconds to absorb secretions [24] [25].

- Sample Processing: Place both swabs in identical, approved viral transport media. Store samples at -20°C within 24 hours if not processed immediately.

- Laboratory Analysis: Test all samples using a highly sensitive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay for the target pathogen(s) (e.g., influenza A/B). Include an internal control (e.g., human RNase P) to monitor sample quality and cellular content [24].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the ANS using the NP swab result as the reference standard. Compare cycle threshold (Ct) values between paired positive samples using non-parametric tests like the Mann-Whitney U test [26] [12].

Protocol for Self-Collection Feasibility and Usability Study

This protocol is critical for tests intended for home use, a key area of regulatory evolution [28] [12].

- Participant Recruitment: Enroll a diverse cohort of participants representative of the intended-use population, varying in age, education, and technical proficiency.

- Training and Sample Collection: Provide participants with the swab kit and standardized, written instructions for self-collection. No direct demonstration should be given. Participants then self-collect an ANS or oral-nasal sample. A healthcare professional subsequently collects an NP swab from the same participant.

- Usability Assessment: Participants complete a questionnaire rating the ease of use, clarity of instructions, and comfort level associated with the self-collection process.

- Analysis: Determine the percent agreement between the results of the self-collected sample and the professionally collected NP sample. Analyze usability feedback to identify potential points of user error or confusion that must be addressed before regulatory approval [28].

Visualization of Regulatory Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The regulatory journey and experimental validation of new sampling methods can be visualized through the following diagrams.

Regulatory Pathway for Novel Sampling Devices

Figure 1: The U.S. FDA pathway for a novel anterior nasal swab. The first device typically requires a De Novo request. Once classified as Class II, it becomes a predicate for subsequent 510(k) submissions [28].

Paired-Sample Validation Workflow

Figure 2: Core workflow for validating an anterior nasal swab against the nasopharyngeal swab reference standard. Key steps include paired sampling and comparative RT-PCR analysis [24] [26] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation of alternative sampling methods relies on a standardized set of high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for conducting these studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sampling Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Flocked Swabs | Sample collection; nylon fibers maximize cellular absorption and elution [30]. | Copan FLOQSwabs, Rhinoswab; tip material (nylon, polyester) is critical for sample release efficiency [24] [26]. |

| Viral Transport Media (VTM) | Preserve viral nucleic acid integrity during transport and storage. | Copan Universal Transport Media, Mantacc VTM; must contain additives to inhibit bacterial/fungal growth [26] [12]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-purity viral RNA for downstream molecular analysis. | QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), Maxwell HT Viral TNA Kit (Promega); automation compatibility (e.g., QIAcube, Hamilton Star) is key for high-throughput processing [24] [12]. |

| RT-PCR Master Mix | Amplify and detect target viral RNA sequences. | Luna Universal Probe One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (NEB), Fast Viral Master mix (Life Technologies); sensitivity and robustness are paramount [26] [12]. |

| Respiratory Panel Assays | Multiplex detection of common respiratory pathogens from a single sample. | Allplex RP1/2/3 & SARS-CoV-2 (Seegene), Lab-developed multiplex PCR; essential for comprehensive pathogen detection and co-infection studies [24] [12]. |

| Internal Control Targets | Monitor sample adequacy, nucleic acid extraction, and PCR inhibition. | Human RNase P gene; confirms sufficient human cellular material in ANS specimens [24]. |

The regulatory landscape for alternative sampling methods is maturing, with anterior nasal swabs emerging as a validated and patient-centric option for influenza and other respiratory virus detection. While nasopharyngeal swabs remain the sensitivity benchmark, robust evidence demonstrates that ANS provide a strong balance of diagnostic accuracy, patient comfort, and practicality for both clinical and potential home settings [29] [27].

Future developments will focus on standardizing self-collection protocols, optimizing swab design and materials for maximum viral recovery, and further integrating these methods with rapid point-of-care and at-home diagnostic platforms. For researchers and drug development professionals, successfully navigating this evolving landscape requires a firm grasp of regulatory pathways, a commitment to rigorous experimental validation, and the strategic use of standardized, high-quality research tools. The continued validation and regulatory acceptance of these methods will be crucial for enhancing pandemic preparedness and expanding access to critical diagnostic testing.

Technical Protocols and Implementation Strategies for Anterior Nasal Collection

Standardized Anterior Nasal Swab Collection Techniques and Materials

Anterior nasal (AN) swabs have emerged as a critical tool for respiratory virus detection, balancing diagnostic accuracy with significant practical advantages. This guide provides a comparative analysis of AN swab performance against traditional nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs, focusing on technical specifications, validated collection protocols, and experimental data directly applicable to influenza detection research. Evidence confirms that while AN swabs may exhibit a modest reduction in sensitivity for some pathogens, their excellent patient tolerance and suitability for self-collection make them a transformative methodology for large-scale public health testing and surveillance studies. Standardization of collection techniques and materials is paramount to ensuring data quality and reproducibility in influenza research.

Performance Comparison: Anterior Nasal vs. Nasopharyngeal Swabs

Extensive clinical evaluations provide a quantitative foundation for selecting appropriate swab types in research protocols. The following tables summarize key performance metrics for SARS-CoV-2 detection, which serve as a relevant proxy for understanding performance in influenza virus detection due to similar transmission routes and specimen requirements.

Table 1: Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity of AN vs. NP Swabs

| Evaluation Focus | Swipe Type | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Agreement (κ statistic) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Ag-RDT (Sure-Status) | NP Swab | 83.9% (76.0–90.0) | 98.8% (96.6–9.8) | 0.918 | [8] |

| AN Swab | 85.6% (77.1–91.4) | 99.2% (97.1–99.9) | [8] | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 Ag-RDT (Biocredit) | NP Swab | 81.2% (73.1–87.7) | 99.0% (94.7–86.5) | 0.833 | [8] |

| AN Swab | 79.5% (71.3–86.3) | 100% (96.5–100) | [8] | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR | NP Swab | 92.5% (85–99) | N/A | N/A | [31] |

| AN Swab | 82.4% (72–93) | N/A | N/A | [31] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR | Saliva | 93.8% (86.0–97.9) | 97.8% (95.3–99.2) | 0.912 | [32] |

| AN Swab | 86.3% (76.7–92.9) | 99.6% (98.0–100.0) | 0.889 | [32] |

Table 2: Analytical and Practical Characteristics Comparison

| Characteristic | Anterior Nares (AN) Swab | Nasopharyngeal (NP) Swab | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collection Depth | 0.5 - 2 cm into nostril [11] [33] | ~8-11 cm to nasopharynx [31] | AN swabs enable self-collection, ideal for decentralized trials. |

| Patient Discomfort | Significantly lower pain and sneeze/cough induction [11] | Significantly higher; requires clinician collection [11] [33] | Reduces participant burden, improves compliance in longitudinal studies. |

| Viral Load Recovery | Lower median load vs. NP (e.g., 1,792 vs. 53,560 RNA copies/mL) [11] | Highest reported viral load [11] [25] | Impacts Limit of Detection (LoD) for low viral titer infections. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | Comparable to NP for Ag-RDTs [8] | Slightly lower for some PCR assays [25] | AN swabs highly reliable for detecting infectious, high viral load stages. |

| Specimen Type Flexibility | Suitable for Ag-RDTs and most NAATs [8] [25] | Considered gold standard for NAATs [25] [31] | AN swabs are versatile for both rapid and lab-based testing. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the validity and reliability of data obtained using AN swabs, researchers should adhere to rigorously validated collection and processing protocols. The following methodologies are drawn from cited clinical studies.

Protocol: Healthcare Worker-Collected AN Swab for Antigen Testing

This protocol is adapted from a prospective diagnostic evaluation that demonstrated equivalent accuracy between AN and NP swabs for SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection [8].

- Step 1: Material Preparation. Use a flocked or foam swab with a polystyrene handle. The swab should be sterile and individually wrapped. Test kits (e.g., Sure-Status, Biocredit) and a timer must be ready.

- Step 2: Sample Collection.

- Insert the swab into one nostril, advancing it approximately 2 cm along the nasal septum and inferior concha, touching the nasal membrane [11].

- Firmly rotate the swab 5 times against the nasal wall [11].

- Hold the swab in place for 5 seconds to ensure adequate specimen absorption [11].

- Without removing the swab, repeat the rotation in the same nostril.

- Use the same swab to repeat the entire procedure in the second nostril [33].

- Step 3: Sample Processing.

- Immediately insert the swab into the extraction buffer vial provided with the test kit.

- Rotate the swab vigorously at least 5 times while pressing the head against the bottom and side of the vial.

- Remove the swab while squeezing the vial wall to extract as much liquid as possible.

- Close the vial with the cap with the integrated dropper.

- Step 4: Test Execution and Interpretation.

- Add the number of drops specified in the manufacturer's Instructions for Use (IFU) to the sample well of the test cassette.

- Start the timer and read the result at the exact time specified in the IFU (e.g., 15-30 minutes).

- Critical Note: Studies indicate test line intensity can be lower with AN swabs. Results should be interpreted by trained personnel, as faint lines can be misclassified by lay users [8].

Protocol: Self-Collection of AN Swab for Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing (NAAT)

This protocol is validated for PCR testing and is crucial for enabling large-scale, decentralized research studies [32] [25].

- Step 1: Participant Instruction. Provide subjects with clear, illustrated instructions. Key points include:

- Insert the swab 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch (approx. 1-2 cm) into the nose [33].

- Rotate the swab against the inner nasal wall in a circular motion 3-5 times.

- Use the same swab to repeat the process in the other nostril.

- Step 2: Sample Collection. The participant follows the provided instructions to self-swab both nostrils with the same swab.

- Step 3: Sample Storage and Transport.

- Place the swab immediately into a tube containing Universal Transport Medium (UTM) or another appropriate transport medium [8] [11].

- Break or cut the swab shaft to secure the lid.

- Store and transport samples refrigerated (4°C) and process them as soon as possible, ideally within 72 hours, to maintain RNA stability [25].

The workflow for a head-to-head validation study, incorporating these protocols, is illustrated below.

Research Validation Workflow for AN Swabs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of AN swab protocols relies on specific materials and reagents. The following table details essential components for a robust research pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for AN Swab Studies

| Item | Specification / Example | Research Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AN Swab | Flocked (e.g., HydraFlock), Foam (e.g., Puritan 25-1506), or Polyester tip [33] | Specimen collection from anterior nares. | Flocked tips show superior specimen release. Ensure swab length and tip are appropriate for nasal anatomy. |

| Transport Medium | Universal Transport Medium (UTM) [8] [11] | Preserves viral nucleic acid/antigen integrity during transport. | Essential for NAAT; not always required for point-of-care Ag-RDTs. |

| Lysis Buffer | Kit-provided (e.g., Sure-Status, Biocredit) [8] | Extracts and exposes viral antigens or nucleic acids. | Buffer composition is test-specific; do not interchange between brands. |

| Reference Assay | RT-qPCR (e.g., TaqPath COVID-19, Allplex SARS-CoV-2) [8] [31] | Provides gold-standard comparison for validation studies. | Targets should include multiple genes (N, ORF1ab, S) for high specificity. |

| Positive Control | Quantified in vitro-transcribed RNA [8] | Standard curve generation for determining viral load/LoD. | Critical for analytical sensitivity measurements and assay calibration. |

Critical Analysis for Research Application

The decision to adopt AN swabs in influenza research requires careful consideration of the trade-offs involved.

Advantages and Rationale for Adoption: The primary strength of AN swabs lies in their practical superiority. Their minimal invasiveness significantly reduces participant discomfort, which is a major ethical and practical advantage in large-scale or serial sampling studies [11]. This facilitates high compliance rates. Furthermore, the ability to be self-collected under guidance enables decentralized clinical trials and community-based surveillance, reducing the need for clinical visits and specialized healthcare workers for sample collection [32] [33].

Limitations and Mitigation Strategies: The core limitation is the potential for reduced analytical sensitivity, particularly when compared to NP swabs in PCR-based detection. Meta-analyses for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR indicate AN specimens can be 12-18% less sensitive than NP swabs [8]. This is likely due to lower recovered viral loads, as directly measured in comparative studies [11] [25]. To mitigate this, AN swabs are ideally deployed for detecting cases with higher viral loads, which are typically the most infectious individuals. For maximum case detection in a study, a combined sampling approach (e.g., AN swab plus saliva) has been shown to increase sensitivity significantly [32] [31].

The relationship between swab type, viral load, and detection success is a key conceptual model for researchers, summarized in the following diagram.

Swab Performance Across Viral Loads

This guide objectively compares the performance of various self-collection protocols for respiratory virus detection, with a specific focus on influenza. The emergence of at-home testing, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has necessitated the development of robust instructional design and rigorous usability testing to ensure sample quality comparable to clinician-collected specimens. This review synthesizes experimental data on the diagnostic accuracy, usability, and feasibility of different self-collection methods, including anterior nasal, oral-nasal, and saliva sampling. The analysis is framed within the broader research context of validating anterior nasal swabs for influenza detection, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comparative evaluation of protocols based on empirical evidence.

The paradigm for diagnostic testing for respiratory pathogens has shifted significantly with the development and validation of self-collection protocols. These protocols enable individuals to collect their own nasal, oral, or saliva samples without direct supervision by healthcare workers, thereby expanding testing access, reducing exposure risks, and alleviating burdens on healthcare systems [34] [35]. For influenza detection specifically, self-collection methods present a promising avenue for widespread surveillance and early diagnosis, yet their validity hinges on two critical components: intuitively designed instructions that untrained users can successfully follow, and demonstrable usability across diverse populations.

The instructional design for self-collection kits must account for users with no prior medical or laboratory training, guiding them through the process of obtaining a sample of sufficient quality for molecular detection. Concurrently, usability testing provides the empirical foundation to validate that these instructions are effective and that the resulting samples meet analytical standards [34] [36]. This review systematically compares the performance of various self-collection approaches, detailing their experimental validation, and places these findings within the ongoing research validation of anterior nasal swabs for influenza detection.

Comparative Performance of Self-Collection Methods

The diagnostic performance of self-collected specimens varies by collection method, pathogen, and viral load. The following data summarize key findings from recent studies, providing a comparative basis for protocol selection.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Self-Collected Specimens for Respiratory Viruses

| Collection Method | Target Pathogen | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Agreement (Kappa or %) | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Nasal Swab | SARS-CoV-2 | 77.3 - 81.0 (PPA) [37] | 85.5 - 87.0 (NPA) [37] | 100% sample adequacy (RNase P) [35] | Performance comparable to HCW-collected NP swabs in high viral load cases (Ct ≤30) [37] |

| Oral-Nasal Swab | Influenza A/B | 67.0 [12] | 96.0 [12] | Kappa: 0.68 [12] | Lower sensitivity for influenza vs. RSV; not a comparable substitute for NP swab [12] |

| Oral-Nasal Swab | RSV | 75.0 [12] | 99.0 [12] | Kappa: 0.79 [12] | Better performance for RSV than for influenza [12] |

| Saliva | SARS-CoV-2 | 80.5 - 86.7 (PPA) [37] | 87.0 (NPA) [37] | Not reported | PPA increased to 81.2-82.1% with Ct ≤30 [37] |

| Pediatric Anterior Nasal | SARS-CoV-2 | Not reported | Not reported | 97.3% success rate (low errors) [38] | Feasible for school-aged children; mean collection time: 70 seconds [38] |

PPA: Positive Percent Agreement; NPA: Negative Percent Agreement; NP: Nasopharyngeal; HCW: Healthcare Worker; Ct: Cycle Threshold.

The data reveal that self-collected anterior nasal swabs perform reliably for SARS-CoV-2 detection, particularly in individuals with high viral loads, which is often the case in early infection when transmission risk is highest [37]. Conversely, the oral-nasal swab method shows suboptimal and variable sensitivity for influenza compared to RSV, indicating that the optimal self-collection method may be pathogen-dependent [12]. This underscores the importance of context-specific validation, especially for influenza-focused research. Furthermore, studies demonstrate that self-collection is not only feasible for adults but also for school-aged children, with high success rates and low error rates observed in supervised school settings [38].

Instructional Design and Usability Testing Protocols

Core Components of Instructional Design

Effective instruction is a cornerstone of successful self-collection. Usability studies have identified several critical elements for instructional design, typically encapsulated in an Instructions for Use (IFU) document. Key components include:

- Visual and Textual Guidance: Combining clear graphics with simple, step-by-step text is essential. A study on an at-home SARS-CoV-2 kit found that user feedback led to improvements in wording and graphics for critical tasks like placing the label correctly on the tube [34] [36].

- Multi-Modal Support: Providing supplementary materials, such as video tutorials, enhances understanding and proper technique. In one study, participants were given written instructions and access to a video tutorial designed in accordance with international guidelines [35].

- Task Breakdown: Instructions must break down the process into manageable steps, from swab unpacking and sample collection to placement in transport media and final packaging [34].

Methodologies for Usability Testing

Usability testing evaluates whether users can successfully follow the IFU to collect a valid sample. Standard methodologies include:

- Simulated Home Environment: Studies often observe participants without medical training as they follow the IFU in a setting that mimics a home, which helps identify real-world challenges [34] [36].

- Direct Observation and Data Collection: Trained observers record errors, difficulties, and user hesitations without intervening. This is complemented by:

- Post-Collection Surveys: To assess perceived clarity, ease of use, and confidence [35] [36].

- Comprehension Questions: To verify understanding of key instructions [34].

- Specimen Quality Analysis: The ultimate validation is whether the self-collected sample is sufficient for testing, often measured by the detection of a human control gene (e.g., RNase P) via RT-PCR [34] [35].

- Diverse Participant Recruitment: Ensuring the tested population varies in age, education level, and technical proficiency to ensure broad usability [34].

The workflow below illustrates a standardized usability testing process derived from these methodologies.

Figure 1: Usability testing workflow for self-collection protocols.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To facilitate replication and critical appraisal, this section details key experimental protocols from the cited literature.

Human Factors Usability Study for At-Home Kit

A seminal usability study for an at-home anterior nares SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR collection kit provides a robust protocol model [34] [36].

- Objective: To determine the usability of an at-home collection kit, with a primary endpoint of the percentage of samples yielding a valid SARS-CoV-2 test result.

- Subjects: 30 adults with no prior medical, laboratory, or COVID-19 self-collection experience.

- Procedure:

- Subjects were provided with the kit containing a sterile nasal swab, transport tube, IFU, and other packaging components.

- In a simulated home environment, subjects were observed while attempting to use the kit by following the IFU alone.

- Observers documented any errors or difficulties without providing guidance.

- Subjects completed a survey and comprehension questions post-collection.

- Outcome Measures:

Validation of Oral-Nasal Swab for Influenza and RSV

A recent diagnostic validation study compared a self-collected oral-nasal swab to a provider-collected nasopharyngeal swab for influenza and RSV detection [12].

- Objective: To validate a self-collected oral-nasal swab for the detection of influenza and RSV using a multiplex PCR panel.

- Study Population: Consecutive adults presenting to an emergency department with suspected viral upper respiratory tract infection.

- Procedure:

- A healthcare provider collected a nasopharyngeal swab as part of routine care (reference standard).

- Participants then self-collected an oral-nasal swab by swabbing both anterior nares, the buccal mucosa, and the tongue using a flocked swab.

- Both specimens were tested using a laboratory-developed multiplex RT-PCR assay.

- Outcome Measures:

- Sensitivity/Specificity: The oral-nasal swab showed a sensitivity of 0.67 and specificity of 0.96 for influenza, and a sensitivity of 0.75 and specificity of 0.99 for RSV [12].

- Conclusion: The self-collected oral-nasal swab was not an acceptable substitute for a nasopharyngeal swab for influenza, primarily due to suboptimal sensitivity [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents commonly used in the development and validation of self-collection protocols for respiratory virus detection.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Self-Collection Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Flocked Anterior Nasal Swab | Sample collection from the anterior nares. Designed for efficient cell collection and elution. | Puritan Sterile Foam Tipped Applicator [38]; Flocked tapered swab (ESwab, Copan) [35]. |

| Universal Transport Media (UTM) | Preserves viral integrity during transport and storage. | Copan UTM [12]; Phosphate buffered saline [38]; Tube containing 0.9% saline [34]. |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies viral RNA from the specimen for downstream molecular analysis. | MagCore Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit [35]; Maxwell HT Viral TNA Kit [12]. |

| RT-PCR Master Mix | Enzymes and reagents for the reverse transcription and amplification of viral RNA. | TaqPath 1-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix [35]; Luna Universal Probe One-Step RT q-PCR kit [12]. |

| Multiplex RT-PCR Assay | Simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens from a single sample. | BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Panel 2.1 [39]; Allplex SARS-CoV-2/FluA/FluB/RSV Assay [37]. |

| Human Control Assay (e.g., RNase P) | Quality control to confirm that sufficient human cellular material was collected. | Detection of human RNase P gene via qRT-PCR [34] [35]. |

The validation of self-collection protocols, particularly for influenza, remains a critical endeavor in public health and diagnostic development. The experimental data compared in this guide demonstrate that while anterior nasal self-swabbing is a well-validated, user-friendly, and effective method for SARS-CoV-2—with clear implications for influenza research—other methods like oral-nasal swabs may show pathogen-dependent performance and require further optimization. The success of any self-collection protocol is inextricably linked to its instructional design and validation through rigorous human factors usability testing. As research continues, future work should focus on standardizing these protocols, optimizing them specifically for influenza viruses, and exploring their integration with emerging multiplex platforms and home-based testing technologies.

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic revealed critical vulnerabilities in diagnostic supply chains, particularly regarding specimen collection and processing components. This experience underscored the necessity of validating alternative methodologies for respiratory virus detection, forming a crucial thesis context for the validation of anterior nasal swabs for influenza detection research. While nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) collection remains the historical gold standard for respiratory virus testing, its limitations including patient discomfort, need for trained healthcare workers, and supply chain constraints have accelerated research into less invasive alternatives [40] [41]. This guide objectively compares the laboratory performance of anterior nasal swabs against other collection methods, with specific focus on transport media, nucleic acid extraction, and PCR amplification efficiency for influenza detection, providing researchers with evidence-based protocols and analytical frameworks for diagnostic development.

Comparative Performance of Specimen Collection Methods

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Swab Types and Collection Sites

Multiple clinical studies have directly compared the performance of anterior nasal swabs to nasopharyngeal swabs for respiratory virus detection. The diagnostic accuracy varies significantly depending on the specific pathogen and collection method.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Anterior Nasal Swabs Compared to Nasopharyngeal Swabs

| Virus Target | Collection Method | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | ANS (Rhinoswab) | 80.7% (73.8-86.2) | 99.6% (97.3-100) | 99.3% (95.5-100) | 87.9% (83.3-91.4) | n=412, OP/NP reference [41] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | ANS (standard) | 72.5% (58.3-84.1) | 100% (99.3-100) | 100% | 98.5% | n=862, NP reference [11] |

| Influenza A/B | Oral-Nasal (self) | 67% (49-81) | 96% (89-99) | N/R | N/R | n=128, NP reference [12] |

| RSV | Oral-Nasal (self) | 75% (43-95) | 99% (93-100) | N/R | N/R | n=128, NP reference [12] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Anterior Nares (self) | 82-84% (66-94) | N/R | N/R | N/R | vs. NP RT-PCR [42] |

For influenza detection specifically, a 2025 validation study found that self-collected oral-nasal swabs (swabbing both anterior nares along with the tongue and buccal mucosa) showed suboptimal test characteristics compared to healthcare provider-collected nasopharyngeal swabs, with a sensitivity of 67% (95% CI: 49-81%) and specificity of 96% (95% CI: 89-99%) [12]. This indicates that while anterior nasal collection methods show promise for SARS-CoV-2 detection, further optimization is required for reliable influenza detection, particularly concerning self-collection protocols.

Viral Load Recovery Across Collection Methods

Viral concentration, as measured by cycle threshold (Ct) values in RT-PCR, provides crucial information about the efficiency of viral recovery across different collection methods.

Table 2: Viral Load Comparison Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Swab Type | Median Viral Load (Copies/μL) | IQR | Ct Value Comparison | PCR-Positive Rate vs. NPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal (NPS) | Flocked | 53,560 | 605-608,050 | Reference | 100% |

| Anterior Nasal (AWN) | NP-type | 1,792 | 7-81,513 | Significantly higher (p<0.001) | 84.4% |

| Anterior Nasal (AWO) | OP-type | 6,369 | 7-97,535 | Significantly higher (p<0.001) | 81.3% |

| Nasal (10 rubs) | Flocked | N/R | N/R | Ct=24.3 | Comparable to NPS |

| Nasal (5 rubs) | Flocked | N/R | N/R | Ct=28.9 (p=0.002) | Lower than 10-rub |

One critical finding from comparative studies is that vigorously rubbed nasal swabs (10 rotations) yielded significantly lower Ct values (median Ct=24.3) compared to those collected with fewer rotations (median Ct=28.9, p=0.002), achieving SARS-CoV-2 concentrations similar to NPS [24]. This demonstrates that collection technique substantially impacts viral load recovery, which has direct implications for optimizing anterior nasal sampling protocols for influenza detection.

Laboratory Processing Methodologies

Transport Media and Swab Material Comparisons

Supply chain limitations during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted systematic evaluation of alternative transport media and swab materials, with implications for influenza testing protocols.

Table 3: Swab and Transport Media Performance for Viral Detection

| Swab Type | Tip Material | Shaft Material | Median Fluid Retention (μL) | Viral Detection Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PurFlock Ultra | Synthetic flocked | Polystyrene | 115 | Comparable to reference |

| FLOQSwab | Synthetic flocked | Polystyrene | 25 | Comparable to reference |

| Puritan Polyester Tip | Polyester | Polystyrene | 127 | Comparable to reference |

| Hologic Aptima | Polyester | Polystyrene | 26 | Comparable to reference |

| Puritan Cotton | Cotton | Aluminum | 13.4 | Comparable to reference |

| MedPro Cotton | Cotton | Wooden | 218 | Comparable to reference |

Research demonstrated no meaningful difference in viral yield across six different swab types when testing for SARS-CoV-2, indicating that multiple swab alternatives could be deployed during supply shortages [43]. Similarly, transport medium comparisons found that DMEM, PBS, 100% ethanol, 0.9% normal saline, and commercial VTM all supported SARS-CoV-2 detection with comparable efficiency when stored at room temperature for up to 72 hours [43]. This robustness across transport conditions provides flexibility for laboratory processing workflows.

Nucleic Acid Extraction and PCR Amplification

Standardized protocols for nucleic acid extraction and PCR amplification are critical for maintaining test sensitivity across different collection methods.

In validation studies for influenza and RSV detection, specimens collected in universal transport media were processed using automated extraction systems. Specifically, a 160-µL aliquot was extracted using the Hamilton Star automated extraction instrument with the Maxwell HT Viral TNA Kit (Promega) [12]. For SARS-CoV-2 detection, comparable workflows employed the NucliSENS EasyMag system or QIAcube with QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kits for nucleic acid extraction [40] [41].

Detection of viral targets was performed using laboratory-developed real-time reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) assays with the Luna Universal Probe One-Step RT-qPCR kit (New England Biolabs) on the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) [12]. Alternatively, commercial panels like the Allplex Respiratory Panels 1/2/3 and Allplex SARS-CoV-2 real-time PCR have been utilized successfully with anterior nasal specimens [24]. Positive specimens are typically defined as those with cycle threshold (Ct) values for the viral target below 37 cycles [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Anterior Nasal Swab Validation Studies

| Category | Specific Product | Function/Application | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collection Swabs | FLOQSwab (Copan) | Synthetic flocked swab for anterior nasal collection | Lower fluid retention (25μL) but excellent viral release [24] [43] |