Viral vs. Non-Viral Vectors for CRISPR Delivery: A 2025 Analysis of Efficiency, Safety, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of viral and non-viral delivery vectors for CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Viral vs. Non-Viral Vectors for CRISPR Delivery: A 2025 Analysis of Efficiency, Safety, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of viral and non-viral delivery vectors for CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational mechanisms of CRISPR delivery, compares the methodological applications and editing efficiencies of different vector systems, and addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing safety and efficacy. Drawing on the latest 2025 clinical trial data and scientific reviews, the content offers a validated, comparative perspective to guide strategic decisions in therapeutic development, from pre-clinical research to clinical application.

The CRISPR Delivery Landscape: Understanding Cargo Formats and Vector Fundamentals

The therapeutic application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system hinges on the efficient delivery of its molecular components into the nucleus of target cells. The choice of how these components are formatted—as plasmid DNA, messenger RNA (mRNA), or preassembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—profoundly influences editing efficiency, specificity, duration of activity, and safety profile. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three core cargo formats, focusing on their performance within the broader context of viral versus non-viral delivery vectors for CRISPR-based therapeutics. Understanding the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each format is essential for researchers to select the optimal strategy for specific experimental or therapeutic goals.

Cargo Format Definitions and Characteristics

Table 1: Core Characteristics of CRISPR/Cas9 Cargo Formats

| Feature | Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | mRNA + gRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Components Delivered | DNA encoding Cas9 and gRNA[s] [1] | Cas9 mRNA and separate gRNA[s] [1] | Precomplexed Cas9 protein and gRNA[s] [1] |

| Nuclear Entry | Required for transcription [1] | Not required (cytosolic translation) | Required for DNA targeting [1] |

| Onset of Activity | Delayed (requires transcription and translation) | Moderate (requires translation) | Immediate [2] |

| Duration of Activity | Prolonged (dependent on promoter and vector) | Transient (mRNA degradation) | Short (protein turnover) [3] |

| Risk of Off-Target Effects | Higher (prolonged Cas9 expression) [3] | Lower (transient expression) [1] | Lowest (short activity window) [1] [3] |

| Immunogenicity | Higher (risk of TLR9 recognition) | Moderate (risk of TLR recognition) | Lower [2] |

The cargo format directly influences the cellular processing and kinetics of the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plasmid DNA (pDNA) delivers the genetic code for Cas9 and the guide RNA, requiring nuclear entry for transcription and subsequent translation into functional protein [1]. In contrast, the mRNA format bypasses the transcription step, allowing for direct translation of Cas9 protein in the cytoplasm, while the gRNA is delivered separately [1]. The Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex represents the most direct approach, involving the delivery of a preassembled, functional Cas9 protein-gRNA complex that is immediately capable of recognizing and cleaving target DNA sequences upon nuclear entry [1] [2].

Performance Comparison: Efficiency, Specificity, and Practicality

Quantitative data from peer-reviewed studies highlight the performance trade-offs between the different cargo formats.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of CRISPR Cargo Formats

| Cargo Format | Reported Editing Efficiency | Delivery Method & Cell Type | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Up to 20% genomic excision [2] | Polymer-based (HPAE-EB) in HEK293 cells [2] | Editing efficiency dropped when translated to primary human keratinocytes [2]. |

| mRNA + gRNA | High efficacy, specific data not quantified [1] | Bioreducible Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) in sensitive cells [1] | Demonstrated high genome editing efficacy and biocompatibility; suitable for transient Cas9 expression with decreased off-target events [1]. |

| RNP Complex | >40% target genomic deletion [2] | Polymer-based (HPAE-EB) in RDEB keratinocytes [2] | Outperformed plasmid DNA delivery in primary cells; minimizes off-target effects and toxicity [1] [2]. |

| RNP Complex | Efficient editing, specific data not quantified [1] | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) in mouse liver and lung [1] | Achieved tissue-specific gene editing in vivo [1]. |

| RNP Complex | High number of INDEL mutations [4] | Transient delivery (DNA-free) into Chicory protoplasts [4] | Produced non-transgenic plants with no risk of unwanted plasmid DNA integration [4]. |

A critical finding from comparative studies is that the performance of a cargo format can be highly context-dependent. For instance, while plasmid DNA mediated 15-20% target genomic excision in HEK293 cells, its efficiency dropped significantly in harder-to-transfect primary human recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) keratinocytes. In the same primary cell model, switching to RNP delivery dramatically increased the editing efficiency to over 40% target genomic deletion [2]. This underscores the importance of considering the target cell type when selecting a cargo format.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: RNP Delivery via Electroporation for Ex Vivo Cell Engineering

This protocol is widely used in clinical applications, such as the FDA-approved therapy CASGEVY (CTX001) for sickle cell disease [1] [3].

- RNP Complex Assembly: Combine synthetic, HPLC-purified gRNA with purified Cas9 nuclease protein in a defined molar ratio (e.g., 6.6:1 gRNA:Cas9) in a nuclease-free duplex buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow for complex formation [2].

- Cell Preparation: Isolate target cells (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells, T-cells) and suspend them in an electroporation-compatible buffer.

- Electroporation: Mix the preassembled RNP complexes with the cell suspension. Electroporate using an optimized program (specific voltage, pulse length, and number of pulses vary by cell type). Using a square-wave system is often beneficial for primary cells.

- Post-Transfection Handling: Immediately after electroporation, transfer cells to pre-warmed culture medium. Assess viability and gene editing efficiency after 48-72 hours. For clinical applications, the edited cells are expanded ex vivo before being infused back into the patient [3].

Protocol 2: Polymer-Based Delivery of CRISPR Cargoes

This protocol uses a highly branched poly(β-amino ester) polymer, HPAE-EB, for in vitro delivery [2].

- Polyplex Formation:

- For DNA/mRNA: Dilute the CRISPR cargo (pDNA or mRNA) and the HPAE-EB polymer separately in 25 mM sodium acetate buffer. Mix the two solutions at a 1:1 volume ratio at optimized weight/weight (w/w) ratios (e.g., 20:1 to 60:1 polymer:DNA). Vortex the mixture for 30 seconds and incubate at room temperature for 10-30 minutes to form stable polyplexes [2].

- For RNP: The anionic nature of the RNP complex (due to the gRNA) allows it to be complexed with cationic polymers similarly to nucleic acids. Dilute the preassembled RNP and polymer separately, then mix at the determined optimal w/w ratio (e.g., 20:1 polymer:RNP) [2].

- Cell Transfection: Add the formed polyplexes to cells at 60-70% confluence. Replace the medium with fresh culture medium after 4 hours post-transfection.

- Analysis: Assess transfection efficiency (e.g., via GFP reporter expression for plasmid DNA) and gene editing outcomes (e.g., via T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing) 48-72 hours post-transfection [2].

Cargo-Vector Integration: A Systems Perspective

The choice of cargo format is intrinsically linked to the selection of the delivery vector, forming an integrated system that dictates the overall success of CRISPR-based therapeutics.

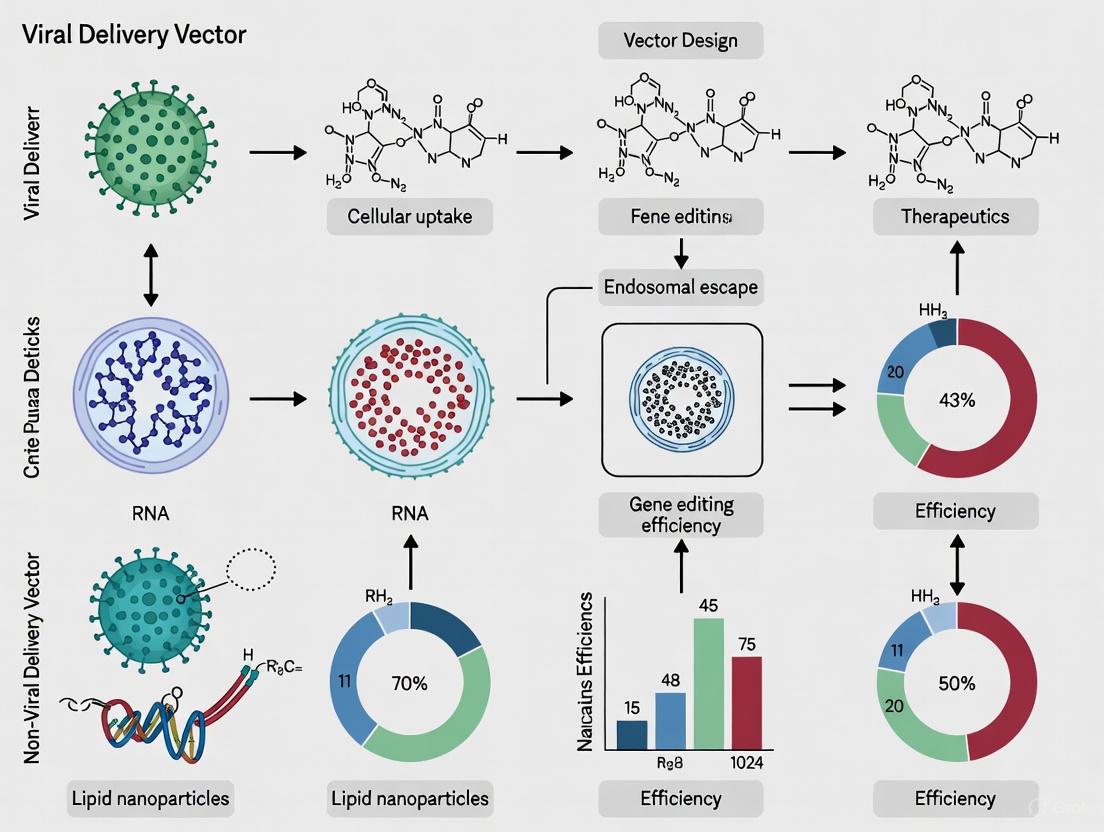

The diagram above illustrates the logical relationships between cargo formats, delivery vectors, and resulting therapeutic outcomes. Viral vectors, such as Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) and Adenoviruses, are predominantly used with DNA-based cargoes (pDNA) for in vivo delivery due to their high transduction efficiency [3]. However, they pose challenges like limited packaging capacity, immunogenicity, and potential for insertional mutagenesis [5] [3]. AAVs, for instance, have a ~4.7 kb packaging limit, which can constrain the delivery of larger Cas9 orthologs [6].

Non-viral vectors, including lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), polymers, and physical methods like electroporation, offer a safer alternative with lower immunogenicity, no risk of insertional mutagenesis, and ease of large-scale production [5] [3]. They are versatile and can deliver all three cargo formats but are particularly well-suited for transient payloads like mRNA and RNP complexes [3]. Electroporation is the gold standard for ex vivo RNP delivery into immune cells and stem cells, as evidenced by its use in approved therapies and clinical trials [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR Cargo Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Highly Branched Poly(β-amino ester) (HPAE-EB) | A lead cationic polymer for non-viral delivery of DNA, mRNA, and RNP complexes in vitro [2]. | Demonstrates high buffering capacity for endosomal escape and can be functionalized to enhance uptake [2]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A clinically advanced platform for in vivo delivery, particularly of mRNA and RNP cargoes [1] [3]. | Modular systems allow for tuning of organ specificity (e.g., via SORT technology) [3]. |

| Electroporation Systems | Physical method for transient RNP delivery into hard-to-transfect primary cells ex vivo [1] [3]. | Critical for clinical workflows (e.g., CAR-T engineering, CASGEVY) [3]. |

| HPLC-Purified Synthetic gRNA | High-purity guide RNA for RNP assembly or co-delivery with mRNA [3]. | End modifications can enhance stability and reduce cytotoxicity, improving editing outcomes [3]. |

| AAV Serotypes (e.g., AAV8, AAV9) | Recombinant AAV vectors for in vivo delivery of DNA cargoes to specific tissues like liver and CNS [6]. | Serotype determines tissue tropism; packaging capacity is limited to ~4.7 kb [6]. |

The selection of a CRISPR cargo format is a fundamental decision that balances editing efficiency, specificity, and safety. Plasmid DNA can be effective but often presents challenges with delivery efficiency in primary cells and a higher risk of off-target effects. mRNA offers a good balance of transient expression and reduced off-target potential compared to pDNA. However, the RNP format consistently demonstrates superior performance in terms of editing efficiency in sensitive primary cells, the highest specificity with minimal off-target effects, and an excellent safety profile. For ex vivo therapeutic applications, particularly in non-dividing or primary cells, RNP delivery via electroporation or advanced non-viral nanoparticles currently sets the benchmark. For in vivo applications, the choice remains context-dependent, with mRNA/LNP and DNA/AAV systems being prominent, though RNP delivery via non-viral vectors is a rapidly advancing field promising to combine the benefits of high efficiency and superior safety.

The transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing extends from basic biological research to clinical therapeutics, offering unprecedented capabilities for precise genomic modifications. The efficacy of this technology is fundamentally governed by two critical phases: the initial delivery of CRISPR components into target cells and the subsequent cellular machinery that repairs the induced DNA breaks. The choice of delivery vector—viral or non-viral—profoundly influences intracellular trafficking, editing efficiency, and ultimate therapeutic success. This guide provides a systematic comparison of delivery system efficiencies, detailing the journey from cellular uptake through the critical DNA repair pathways that execute the desired genetic alterations.

Cellular Uptake Mechanisms and Intracellular Processing

The mechanism by which CRISPR-Cas9 components enter a cell varies significantly depending on the delivery vector, directly impacting editing efficiency and specificity.

Table 1: Comparison of Cellular Uptake Mechanisms by Delivery Method

| Delivery Method | Primary Uptake Mechanism | Intracellular Processing | Onset of Editing Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (AAV, LV, AdV) | Receptor-mediated endocytosis [7] [8] | Endosomal escape, capsid uncoating, genome release [8] | Moderate (requires transcription/translation for DNA delivery) [9] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Endocytosis (lipid raft-dependent) [10] | Endosomal escape via ionizable lipids, release into cytoplasm [7] [10] | Fast (direct activity of RNP or translation of mRNA) [9] |

| Electroporation | Physical membrane disruption [7] | Direct deposition into cytoplasm [7] | Very fast (especially for RNPs) [9] |

| RNP Complexes | Endocytosis (when using carriers) [10] | Endosomal escape, passive nuclear import [9] [10] | Immediate (fully functional complex) [9] |

The journey begins with cellular uptake. Viral vectors like Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) and Lentivirus (LV) exploit receptor-mediated endocytosis, where the viral capsid binds to specific cell surface receptors and is internalized within an endosome [7] [8]. Non-viral methods, such as Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), also rely on endocytosis but are facilitated by the formation of a lipid bilayer around the cargo [10]. Physical methods like electroporation bypass these pathways entirely by creating transient pores in the cell membrane, allowing for direct cytoplasmic entry [7].

Once inside, the cargo must reach the nucleus. Viral vectors have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for endosomal escape and genome release [8]. For non-viral vectors, the key challenge is also endosomal escape, which for LNPs is mediated by ionizable lipids that become protonated in the acidic endosomal environment, leading to membrane disruption and cargo release into the cytoplasm [7] [10]. The final step is nuclear entry. While viral genomes can exploit active nuclear import mechanisms, large Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) rely on passive diffusion through the nuclear pore complex or the use of nuclear localization signals (NLS), which are short amino acid sequences that tag the protein for active nuclear transport [10]. Delivery format significantly influences the timeline for editing: plasmid DNA (slowest) requires nuclear entry, transcription, and translation; mRNA (faster) bypasses transcription; and pre-assembled RNPs (fastest) are immediately active upon nuclear entry [9].

DNA Repair Pathways: NHEJ and HDR

Upon successful nuclear entry, the Cas9 nuclease introduces a double-strand break (DSB) in the target DNA. The cellular response to this break is the most critical determinant of the editing outcome, primarily mediated by two competing repair pathways [11].

1. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) NHEJ is the cell's dominant and most rapid DSB repair pathway. It functions throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating the broken DNA ends together. This process is error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site [12] [11]. In the context of CRISPR-Cas9, these indels can disrupt the coding sequence of a gene, leading to a functional knockout. This makes NHEJ the preferred pathway for gene disruption applications [13] [11].

2. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) HDR is a precise, high-fidelity repair mechanism that operates primarily in the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. It requires a homologous DNA template—which can be supplied as an exogenous donor template—to accurately repair the break [11] [14]. This pathway allows for specific gene corrections, insertions, or nucleotide substitutions, making it essential for therapeutic applications that require precision [14]. However, HDR is inherently less efficient than NHEJ and is limited to dividing cells, presenting a significant challenge for editing non-dividing cells like neurons or cardiomyocytes [11].

Table 2: Characteristics of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Cas9 Editing

| Pathway | Repair Mechanism | Template Required | Efficiency | Primary Outcome | Main Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Ligation of broken ends | No | High (dominant pathway) | Small insertions or deletions (indels) | Gene knockout, gene disruption [13] [11] |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Copying from a homologous template | Yes (donor DNA) | Low (competes with NHEJ) | Precise nucleotide changes or gene insertions | Gene correction, knock-in, specific mutations [11] [14] |

The balance between NHEJ and HDR is crucial. NHEJ is the default pathway, meaning that achieving high HDR efficiency often requires strategic intervention. Common experimental strategies to enhance HDR efficiency include synchronizing cells to the S/G2 phase, using chemical inhibitors of key NHEJ proteins (e.g., Ku70/80 or DNA-PKcs), and optimizing the design and delivery of the donor DNA template [14].

Vector Efficiency and Practical Considerations

The delivery vector choice creates a complex trade-off between efficiency, payload capacity, safety, and applicability.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Viral vs. Non-Viral Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Typical Editing Efficiency | Payload Capacity | Immunogenicity & Safety Concerns | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Moderate to High [9] [8] | Low (~4.7 kb) [15] [8] | Low immunogenicity; mostly episomal, low risk of insertional mutagenesis [15] [8] | In vivo gene therapy; high precision editing with compact Cas9s [15] [8] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | High [9] | High (~8 kb) | Integrates into host genome; risk of insertional mutagenesis; higher immunogenicity [7] [9] | Ex vivo editing (e.g., CAR-T cells); stable long-term expression [7] [9] |

| Adenovirus (AdV) | Moderate [12] | High (up to ~35 kb) [12] | High immunogenicity; transient expression [12] | In vivo delivery of large cargos; vaccination [12] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) | Variable (Moderate to High for liver) [7] [10] | Moderate | Lower immunogenicity than viruses; potential toxicity at high doses [7] | In vivo mRNA/protein delivery; clinical RNAi/CRISPR therapeutics [7] [10] |

| Electroporation (RNPs) | High (ex vivo) [9] | N/A (direct delivery) | Minimal immunogenicity; no genomic integration risk; can be cytotoxic [7] [9] | Ex vivo editing of sensitive cells (e.g., HSCs, T-cells); high-precision editing [9] |

Viral Vector Strategies and Innovations:

- AAVs are favored for in vivo therapy due to their low immunogenicity and high tissue specificity. Their major limitation is a cargo capacity of <4.7 kb, which is insufficient for the standard SpCas9. Solutions include using smaller Cas orthologs (e.g., SaCas9), split-intein systems, or dual-vector approaches where Cas9 and gRNA are delivered separately [15] [8].

- Lentiviruses offer high transduction efficiency and stable long-term expression due to genome integration, but this raises safety concerns about insertional mutagenesis, limiting their use primarily to ex vivo applications [7] [9].

- Adenoviruses have a very high packaging capacity (up to 35 kb for "gutless" versions) but trigger strong immune responses, leading to transient expression and potential toxicity [12].

Non-Viral Vector Strategies and Innovations:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as a powerful platform, particularly for delivering mRNA and RNPs. A key innovation is the inclusion of permanently cationic lipids (e.g., DOTAP) in formulations, which enables efficient RNP encapsulation at neutral pH, preserving protein structure and function [10]. LNPs can be engineered for tissue-specific targeting.

- Electroporation is highly efficient for ex vivo delivery, especially for RNP complexes. It minimizes off-target effects due to transient activity but can reduce cell viability [7] [9].

- RNP Delivery is considered the gold standard for minimizing off-target effects and avoiding immune responses, as the pre-assembled complexes are active immediately upon nuclear entry and rapidly degraded [9] [10].

Successful CRISPR experimentation requires a suite of carefully selected reagents and tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Constructs | Provides the nuclease. Can be plasmid DNA, mRNA, or protein. | Plasmid: cost-effective but persistent expression increases off-target risk. mRNA: transient expression. Protein (for RNP): immediate activity, lowest off-target risk [9]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic locus. | Can be expressed from a plasmid or synthesized in vitro. Specificity is critical to minimize off-target effects [9] [11]. |

| Donor DNA Template | Provides homology for HDR-mediated precise editing. | Can be single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donor. Design with sufficient homology arms [14]. |

| Delivery Vectors | Transports CRISPR components into cells. | Choice depends on application (in vivo vs. ex vivo), target cell type, and cargo size (see Table 3). |

| NHEJ/HDR Modulators | Small molecules or peptides that manipulate repair pathway choice. | Compounds like Scr7 (NHEJ inhibitor) or RS-1 (HDR enhancer) can be used to boost HDR efficiency relative to NHEJ [14]. |

| Cell Synchronization Agents | Chemical agents to arrest cells in S/G2 phase. | Agents like aphidicolin can increase the proportion of cells competent for HDR, thereby boosting precise editing rates [14]. |

The journey of CRISPR-Cas9 from cellular uptake to final DNA repair is a complex process where the choice of delivery vector is inextricably linked to the molecular outcome. Viral vectors like AAV offer sophisticated in vivo delivery but are constrained by packaging limits, while non-viral systems like LNPs and electroporated RNPs provide flexibility and enhanced safety for both in vivo and ex vivo applications. The ultimate genetic outcome hinges on the competition between the error-prone NHEJ and precise HDR pathways, a balance that researchers can now influence through vector selection and experimental strategy. As the field advances, the development of next-generation vectors with improved tissue specificity, reduced immunogenicity, and enhanced capacity to deliver diverse payloads will be paramount to fully realizing the therapeutic potential of precise genome editing.

The therapeutic application of CRISPR technology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical science, offering unprecedented potential for treating genetic disorders, cancers, and other intractable diseases. However, the transformative promise of CRISPR is contingent upon one critical factor: the efficient delivery of editing components to target cells. The efficiency of any CRISPR-based therapeutic is fundamentally governed by three core metrics: transfection rates (the successful delivery of CRISPR machinery into target cells), editing specificity (the precision of on-target editing without off-target effects), and duration of effect (the persistence of the therapeutic outcome). These metrics vary dramatically between the two primary delivery paradigms—viral and non-viral vectors—each with distinct advantages and limitations. This guide provides a structured comparison of these delivery systems, supported by current experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform strategic decisions in therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Vector Performance

The choice of delivery vector directly influences the critical performance metrics of a CRISPR therapeutic. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the most widely used viral and non-viral delivery systems based on current research and clinical data.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CRISPR Delivery Vectors

| Delivery Vector | Transfection Rate/Efficiency | Editing Specificity (On-target vs. Off-target) | Duration of Effect | Primary Cargo Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | High for target tissues (e.g., liver, retina) [15] | High but prolonged expression may increase off-target risk [16] | Long-term (persistent episomal expression) [15] [17] | DNA [17] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | High for dividing and non-dividing cells [17] | Lower due to random genomic integration [17] | Permanent (integration into host genome) [17] | DNA [17] |

| Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) | Variable; high for liver cells [18] [19] | Highest (transient activity reduces off-targets) [16] | Short-term (transient expression) [18] [16] | mRNA, RNP [17] [16] |

| Virus-Like Particle (VLP) | Promising in preclinical models [20] [21] | High (RNP delivery is transient) [17] | Short-term [17] | RNP [17] |

| Spherical Nucleic Acid (SNA) | 3x higher cell entry vs. standard LNP [19] | Improved precision, reduced toxicity [19] | Data emerging (likely transient) [19] | RNP, mRNA [19] |

Key Trade-offs and Decision Factors

The data in Table 1 reveals fundamental trade-offs. Viral vectors, particularly AAV, excel at achieving high transfection rates and sustained long-term effects, which is ideal for monogenic diseases requiring permanent correction [15] [17]. However, their prolonged activity can increase the potential for off-target effects, and their limited packaging capacity restricts the size of CRISPR machinery that can be delivered [15] [16]. In contrast, non-viral vectors like LNPs offer superior safety profiles with transient activity that minimizes off-target effects and avoids genome integration [18] [16]. Their primary limitation is their transient nature, which may necessitate re-dosing, and a current tendency to accumulate primarily in the liver [18] [17]. The recent development of LNP-SNAs demonstrates how novel nanotechnologies can significantly enhance transfection rates and specificity, pointing to a future where these trade-offs may be mitigated [19].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Efficiency Metrics

Robust experimental validation is essential for quantifying the metrics described above. Below are detailed protocols for key assays used to evaluate delivery efficiency and editing outcomes.

Protocol 1: Quantifying Transfection Rate and Efficiency

Objective: To determine the percentage of cells that have successfully internalized CRISPR cargo. Methodology: This can be assessed using a PEG-mediated transfection of a GFP reporter plasmid into isolated protoplasts, as optimized for pea and adaptable to other cell types [22].

Materials:

- Target cells (e.g., cell line, primary cells, or protoplasts)

- GFP reporter plasmid

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) solution (e.g., 20-40%)

- Plasmid DNA (e.g., 20 µg)

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

- Isolate and purify target cells or protoplasts. For plant protoplasts, this involves enzymatic digestion of the cell wall with cellulase and macerozyme [22].

- Incubate the cells with the GFP plasmid and PEG solution. Optimal conditions from one study are 20 µg of plasmid DNA with 20% PEG for 15 minutes [22].

- Wash the cells to remove excess plasmid and PEG.

- Culture the transfected cells for 24-48 hours.

- Analyze using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy to count the percentage of GFP-positive cells. A well-optimized protocol can achieve transfection efficiencies of approximately 59% [22].

Protocol 2: Assessing Editing Specificity and On-target Efficiency

Objective: To confirm precise on-target editing and identify potential off-target effects. Methodology: A combination of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for on-target efficiency and specialized assays for off-target detection.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA from transfected cells

- PCR reagents and primers flanking the target site

- NGS platform

- Off-target prediction software (e.g., Cas-OFFinder)

- Methods like DISCOVER-Seq or targeted amplicon sequencing for suspected off-target sites [21]

Procedure:

- Extract genomic DNA from treated and control cells.

- Amplify the target locus using PCR with specific primers.

- Sequence the amplicons using NGS. The editing efficiency is calculated as the percentage of sequencing reads containing indels or precise edits at the target site. Efficiencies can exceed 90% in some systems [22].

- Predict potential off-target sites in silico using the gRNA sequence.

- Interrogate predicted off-target sites using methods like amplicon sequencing to quantify mis-editing. Novel tools like AutoDISCO are being developed to streamline this clinically [21].

Protocol 3: Evaluating the Duration of Effect

Objective: To measure the persistence of the genomic edit and its functional consequence over time. Methodology: Long-term tracking of edited cell populations and functional biomarkers in vivo.

Materials:

- Animal disease model

- Blood collection supplies

- ELISA kits for disease-specific proteins

- Equipment for functional assessments (e.g., echocardiogram)

Procedure:

- Administer the CRISPR therapeutic to an animal model.

- Collect serial samples (e.g., blood, tissue biopsies) over an extended period (months to years).

- Quantify the persistence of editing in genomic DNA from samples using digital PCR or NGS.

- Monitor a durable functional outcome. For example, in a trial for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), a single dose of an LNP-delivered CRISPR therapy led to a ~90% reduction in the disease-related TTR protein that was sustained for over two years in all participants, demonstrating a long-lasting therapeutic effect from a transiently delivered editor [18].

Visualizing the CRISPR Delivery Workflow and Trade-offs

The following diagrams map the critical decision pathways and experimental workflows for evaluating CRISPR delivery systems.

CRISPR Delivery Vector Decision Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Efficiency Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of the aforementioned protocols requires a suite of specialized reagents. The table below lists key solutions for researchers building a CRISPR delivery workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Delivery and Evaluation

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A chemical facilitator that induces DNA uptake by disrupting the cell membrane [22]. | PEG-mediated transfection of CRISPR constructs into plant protoplasts or hard-to-transfect mammalian cells [22]. |

| Ionizable Lipids | The key functional component of LNPs, enabling encapsulation of nucleic acids and endosomal escape upon cellular entry [17]. | Formulating LNPs to deliver CRISPR mRNA or RNPs for in vivo applications, particularly to the liver [18] [17]. |

| AAV Serotypes (e.g., AAV5, AAV9) | Engineered viral capsids with distinct tropisms for different tissues (e.g., retina, liver, CNS) [15]. | Selecting the optimal serotype (e.g., AAV5 for retinal delivery in EDIT-101) for targeted in vivo CRISPR therapy [15]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer | A recombinant protein that increases the efficiency of homology-directed repair (HDR) without increasing off-target effects [20]. | Enhancing the rate of precise gene insertion or correction when co-delivered with a CRISPR system and a donor DNA template [20]. |

| Cell Strainers (40 μm) | Used to filter out undigested tissue and debris after enzymatic protoplast isolation, yielding a clean single-cell suspension [22]. | Purifying viable protoplasts post-isolation for subsequent transfection experiments [22]. |

| Enzyme Solutions (Cellulase/Macerozyme) | A cocktail of enzymes that digest plant cell walls to release naked protoplasts [22]. | Isating protoplasts from plant tissues like leaves for rapid, high-throughput testing of CRISPR reagent efficiency [22]. |

The strategic selection of a delivery vector is a cornerstone of successful CRISPR therapeutic development, as it directly dictates the triad of efficiency metrics: transfection rate, editing specificity, and duration of effect. Viral vectors like AAV offer the advantage of potent and sustained editing, making them suitable for diseases requiring a one-time, permanent cure, albeit with considerations for packaging limits and potential immunogenicity. Non-viral vectors, particularly LNPs, provide an excellent safety profile with high specificity and re-dosing capability, though their effects are transient and tropism is currently limited. Emerging technologies, such as LNPs engineered for selective organ targeting (SORT) and structurally enhanced nanoparticles like SNAs, are actively breaking these historical constraints, offering a future of more precise, efficient, and versatile CRISPR delivery systems. Researchers must therefore weigh these performance trade-offs against their specific therapeutic goals, using the standardized protocols and tools outlined here, to navigate the complex and rapidly evolving landscape of CRISPR delivery.

The therapeutic application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology represents a frontier in modern medicine, offering potential cures for a range of genetic disorders. Its clinical translation, however, is contingent on the efficient and safe delivery of CRISPR components into target cells. Delivery vectors are broadly categorized into viral and non-viral systems, each with distinct profiles of advantages and limitations. For researchers and drug development professionals, the critical challenges of immunogenicity, cargo size limitations, and off-target effects often dictate the choice of delivery platform. This guide provides an objective comparison of viral and non-viral vector efficiency, synthesizing current experimental data and methodologies to inform strategic decisions in therapeutic development.

Core Challenges in CRISPR Delivery Vector Efficiency

Immunogenicity

The immune response elicited by a delivery vector can compromise both the safety and efficacy of a CRISPR therapy. Viral vectors, due to their biological origin, often pose a higher risk.

- Viral Vectors: Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are favored for their relatively low immunogenicity compared to other viral vectors. They are not known to cause disease in humans and typically provoke mild immune responses [23] [17]. However, pre-existing immunity in human populations remains a concern, and AAVs can still trigger dose-limiting inflammatory responses [23] [15]. In contrast, adenoviral vectors (AdVs) and lentiviral vectors (LVs) are more immunogenic. AdVs are known to cause strong immune reactions, while LVs, with an HIV-derived backbone, present significant safety implications that limit their in vivo use [17] [9].

- Non-Viral Vectors: Systems like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and polymeric nanoparticles generally exhibit minimal safety and immunogenicity concerns due to the absence of viral components [17] [24]. Their synthetic nature makes them less recognizable to the immune system. A key clinical advantage of LNPs, as demonstrated in trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and a personalized therapy for CPS1 deficiency, is the possibility of redosing without the severe immune reactions typically associated with viral vector re-administration [18].

Cargo Size Limitations

The packaging capacity of a vector is crucial for delivering the relatively large CRISPR-Cas9 system.

- Viral Vectors: The ~4.7 kb packaging capacity of AAVs is a major constraint. The commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is approximately 4.2 kb, leaving insufficient space for additional essential elements like promoters and guide RNA(s) [23] [15]. This has spurred the development of innovative workarounds, such as:

- Non-Viral Vectors: Nanocarriers such as LNPs, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), and extracellular vesicles (EVs) do not face the same strict size limitations as AAVs [17] [25]. They can be engineered to accommodate various forms of CRISPR cargo—plasmid DNA, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—without being constrained by a fixed payload size [24] [25]. This flexibility allows for the delivery of larger CRISPR systems or multiple editing components simultaneously.

Off-Target Effects

Off-target effects refer to unintended edits at genomic sites with sequences similar to the target, a key concern for therapeutic safety.

- Viral Vectors: Vectors like AAVs and LVs often lead to prolonged expression of the Cas9 nuclease because they maintain the editing machinery inside cells for an extended period (via episomal persistence or genomic integration). This sustained activity increases the window for off-target cleavage [23] [9].

- Non-Viral Vectors: Delivery of pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes is associated with the lowest off-target effects. RNP activity is transient, as the complex is rapidly degraded by cellular proteases, minimizing the time for unintended edits to occur [17] [9]. This transient nature is a primary reason why the first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy, Casgevy for sickle cell disease, utilizes RNP delivery via electroporation ex vivo [9].

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Viral and Non-Viral Delivery Vectors

| Challenge | Vector Type | Key Characteristics | Experimental Evidence & Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity | Viral (AAV) | Low to moderate immunogenicity; pre-existing immunity is a concern; re-dosing is typically not possible. | Clinical trials for hATTR (NCT04601051) show manageable immune responses, but high doses can trigger inflammation [18] [15]. |

| Viral (Lentivirus) | Moderate immunogenicity; safety concerns due to genomic integration. | Primarily used ex vivo; FDA-approved for CAR-T therapies (e.g., Kymriah) but not for in vivo CRISPR delivery [17] [9]. | |

| Non-Viral (LNP) | Low immunogenicity; enables re-dosing. | Successful redosing demonstrated in a Phase I hATTR trial and a personalized CPS1 deficiency case with no serious side effects [18]. | |

| Cargo Size Limitations | Viral (AAV) | Strict ~4.7 kb limit. | Strategies to overcome this: SaCas9 (3.2 kb) showed therapeutic efficacy in mouse models; dual-AAV systems for SpCas9 are in development [15]. |

| Non-Viral (Nanocarriers) | High flexibility; no strict size limit. | LNPs successfully deliver Cas9 mRNA (>>4.7 kb) for in vivo editing in liver targets [18] [24]. | |

| Off-Target Effects | Viral (AAV/Lentivirus) | Sustained Cas9 expression; higher risk of off-target edits. | In vivo studies show persistent Cas9 expression for weeks; inducible systems can help mitigate this [23] [9]. |

| Non-Viral (RNP) | Transient activity; fastest clearance; lowest off-target risk. | NGS-based assays (GUIDE-seq) show RNP delivery reduces off-targets compared to plasmid DNA delivery [17] [26] [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Key Challenges

Protocol for Evaluating Immunogenicity

Objective: To quantify innate and adaptive immune responses to a CRISPR delivery vector in a murine model. Methodology:

- Administration: Systemically administer the CRISPR-loaded vector (e.g., AAV8 or LNP) to mice via tail-vein injection. Include a control group receiving empty vector or buffer.

- Sample Collection: Collect blood and tissue (e.g., liver, spleen) samples at 6, 24, and 72 hours post-injection, and again at 1-2 weeks.

- Cytokine Analysis: Use a multiplex cytokine ELISA on serum to quantify pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ). A significant increase indicates activation of the innate immune system.

- Immune Cell Profiling: Isolate immune cells from the spleen and liver. Use flow cytometry to characterize immune cell populations (e.g., T-cells, B-cells, macrophages, neutrophils) and their activation states.

- Antibody Detection: At later time points (e.g., 2 weeks), use an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect the presence of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against the vector (e.g., AAV capsid) or the Cas9 protein itself.

Protocol for Testing Cargo Delivery Efficiency

Objective: To assess the functional delivery of CRISPR components and subsequent editing efficiency. Methodology:

- In Vitro Transduction/Transfection: Deliver the CRISPR vector (e.g., AAV, LNP-RNP) to cultured target cells.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-delivery and extract genomic DNA.

- Editing Efficiency Analysis:

- T7 Endonuclease I Assay: PCR-amplify the target genomic region. Digest the heteroduplexed PCR product with T7EI, which cleaves DNA at mismatched bases. Analyze fragments by gel electrophoresis; the ratio of cleaved to uncleaved products indicates editing efficiency.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For a more quantitative and comprehensive measurement, amplify the target region and subject it to NGS. The percentage of reads containing insertions or deletions (indels) at the target site provides a precise measure of editing efficiency.

Protocol for Detecting Off-Target Effects

Objective: To identify and quantify unintended genomic edits genome-wide. Methodology:

- Cell Treatment: Treat cells with the CRISPR delivery system.

- Genome-Wide Profiling: Use an advanced sequencing-based method to identify potential off-target sites. GUIDE-seq is a widely adopted method:

- A short, double-stranded oligonucleotide tag is introduced into cells alongside the CRISPR system during transfection. This tag is incorporated into DSBs generated by Cas9.

- Genomic DNA is extracted and subjected to NGS. The locations of tag integration reveal potential off-target cleavage sites across the entire genome [26].

- Validation: Potential off-target sites identified by GUIDE-seq are validated by targeted amplicon sequencing to confirm and quantify the frequency of indels at those loci.

Visualization of Vector Challenges and Solutions

The following diagram illustrates the key challenges and primary strategies for both viral and non-viral CRISPR delivery systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for CRISPR Delivery Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 Plasmid | Expresses the full-length Cas9 nuclease from S. pyogenes. Used for stable, long-term editing. | Creating stable cell lines for gene knockout studies [23] [9]. |

| SaCas9 Plasmid | A compact Cas9 variant (~1 kb smaller than SpCas9). Essential for AAV-based delivery. | Packaging into a single AAV vector for in vivo gene therapy applications [15]. |

| Cas9 mRNA | In vitro transcribed mRNA for Cas9 translation. Offers transient expression. | Delivery via LNPs for in vivo editing with reduced off-target risk compared to plasmids [9]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and sgRNA. Provides immediate, transient activity with high specificity. | Gold-standard for ex vivo editing (e.g., Casgevy); delivered via electroporation [17] [9]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic nanocarriers for encapsulating and delivering nucleic acids (DNA, mRNA) or RNPs. | Leading platform for systemic, in vivo non-viral delivery, particularly to the liver [18] [24]. |

| AAV Serotype Library | Different AAV capsids (e.g., AAV2, AAV8, AAV9) with varying tissue tropisms. | Screening for optimal transduction efficiency in a specific target tissue (e.g., liver, muscle, CNS) [15] [9]. |

| GUIDE-seq Kit | A complete reagent set for genome-wide identification of off-target cleavage sites. | Profiling the safety and specificity of a novel gRNA or delivery method [26]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | An enzyme that cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA. | A cost-effective and rapid method for initial assessment of on-target editing efficiency [25]. |

The choice between viral and non-viral delivery vectors for CRISPR therapeutics involves a critical trade-off between efficiency and safety. Viral vectors, particularly AAVs, offer high transduction efficiency and durable expression but are constrained by immunogenicity and cargo size. Non-viral vectors, especially LNPs delivering RNP or mRNA, provide superior safety, reduced immunogenicity, and transient activity but often require optimization for delivery efficiency beyond the liver. The evolving landscape, marked by the first approved therapies and advanced clinical trials, indicates a future where the selection of a delivery system will be highly tailored to the specific disease, target tissue, and desired duration of therapy. Innovations in vector engineering, such as novel AAV capsids and smart non-viral nanomaterials, continue to push the boundaries toward safer and more effective CRISPR-based medicines.

Delivery in Action: Viral and Non-Viral Vector Mechanisms and Workflows

The advancement of CRISPR-based therapeutics is intrinsically linked to the development of efficient and safe delivery vectors. Viral vectors, particularly Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV), Lentivirus (LV), and Adenovirus (Ad), have emerged as the primary vehicles for transporting CRISPR machinery into target cells. These vectors offer distinct advantages and limitations based on their structural biology, tropism, and genomic integration capabilities. The selection of an appropriate viral vector is a critical determinant in the success of gene editing experiments and therapies, influencing factors such as editing efficiency, specificity, duration of expression, and immunogenic response. This guide provides a objective comparison of these three viral vector systems, focusing on their application in CRISPR therapeutics research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Vector Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

The fundamental biological and functional characteristics of AAV, Lentivirus, and Adenovirus directly inform their suitability for specific research applications.

Core Structural and Functional Properties

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV): AAV is a small, non-enveloped virus with a single-stranded DNA genome of approximately 4.7 kb, flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) that are essential for genome packaging and replication [27] [28]. Its icosahedral capsid, composed of VP1, VP2, and VP3 proteins, determines serotype-specific tissue tropism [27]. AAV is replication-deficient and requires helper virus functions (typically from adenovirus) for productive infection. For recombinant AAV (rAAV) production, the native

repandcapgenes are replaced with the therapeutic transgene cassette, resulting in a vector that persists primarily as episomal DNA in the host cell nucleus, enabling long-term transgene expression without integration-related risks [28].Lentivirus (LV): Lentiviruses are enveloped viruses belonging to the retrovirus family, characterized by an RNA genome that is reverse-transcribed into DNA upon host cell entry [29]. The viral core is often conical or bullet-shaped and houses the genome along with essential enzymes like reverse transcriptase and integrase [27]. A key feature of recombinant Lentiviral vectors (rLVs) is their ability to infect both dividing and non-dividing cells. Their genome integrates into the host chromosome, facilitating long-term transgene expression, which is particularly valuable for ex vivo cell engineering applications [29]. Lentiviral vectors are commonly pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus G-glycoprotein (VSV-G) to broaden cellular tropism and enhance particle stability [29] [30].

Adenovirus (Ad): Adenovirus is a non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus with a larger native genome (~36 kb) and an icosahedral capsid [31]. The capsid features fiber proteins that mediate initial attachment to host cell receptors. Adenoviral vectors are characterized by high transduction efficiency across a wide range of dividing and non-dividing cells and can accommodate large transgene payloads (up to approximately 37 kb in helper-dependent "gutted" vectors). They remain episomal in the nucleus and do not integrate into the host genome, leading to robust but transient transgene expression due to eliciting strong cellular immune responses against transduced cells [31].

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters

The table below summarizes the critical characteristics of AAV, Lentivirus, and Adenovirus vectors for direct comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Viral Vector Systems

| Parameter | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (Ad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Type | Single-stranded DNA | Single-stranded RNA (reverse transcribed to DNA) | Double-stranded DNA |

| Packaging Capacity | ~4.7 kb [27] | 8-12 kb [27] | ~8 kb (1st/2nd gen.); up to ~37 kb (helper-dependent) |

| Genomic Integration | Predominantly episomal [27] | Integrates into host genome [29] | Episomal [31] |

| Transgene Expression Duration | Long-term (months to years) [28] | Long-term (stable in dividing cells due to integration) [29] | Short-term (days to weeks) due to immune clearance |

| Typical Applications | In vivo gene therapy, CRISPR delivery to non-dividing cells (e.g., neurons, retina) [32] [33] | Ex vivo cell engineering (e.g., CAR-T, HSCs), in vivo delivery to dividing/non-dividing cells [29] | Vaccines, oncolytic therapy, transient gene expression, large gene delivery [31] |

| Primary Tropism/ Targeting | Serotype-dependent (e.g., AAV9 for CNS, AAV5 for lungs, AAV8 for liver) [27] [34] | Broad (can be pseudotyped, e.g., VSV-G for wide tropism) [29] | Broad native tropism; can be retargeted using antibody conjugates [31] |

| Immunogenicity | Relatively low; pre-existing antibodies common [29] | Moderate | High; limits repeat administration |

| Production Yield | Challenging; lower yields, issue of empty capsids [27] [35] | High production yields [27] | Very high titers achievable |

Application in CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

The delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components—typically the Cas nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA)—poses specific challenges and requirements that are met differently by each vector system.

Performance in CRISPR Workflows

AAV for CRISPR: AAV's small packaging capacity is its primary limitation for CRISPR delivery. A single AAV vector cannot package the coding sequence for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9, ~4.2 kb) along with its gRNA and necessary promoters. Researchers employ strategies to overcome this, including:

- Dual AAV Systems: The Cas9 and gRNA expression cassettes are split across two separate AAV vectors [32].

- Smaller Cas Orthologs: Using smaller Cas proteins like Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9) or Cas13d that can fit into a single AAV particle with their gRNA [34] [33].

- All-in-one Systems: For smaller CRISPR systems, a single vector can deliver all components for applications like gene knockdown [34]. AAV is the leading platform for in vivo CRISPR delivery due to its ability to transduce non-dividing cells and mediate long-term expression from a single administration, which is crucial for therapeutic applications in tissues like the CNS and retina [33] [28].

Lentivirus for CRISPR: Lentivirus's larger cargo capacity readily accommodates both SpCas9 and single or multiple gRNAs within a single "all-in-one" vector, simplifying experimental workflows [27] [29]. Its integrating nature ensures persistent expression of CRISPR components, which is desirable for long-term gene disruption in dividing cells or for genetic screens. However, sustained Cas9 expression increases the potential for off-target effects and immune responses. Lentiviral vectors are predominantly used for ex vivo CRISPR applications, such as engineering CAR-T cells or creating stable knockout cell lines, where their ability to transduce a wide variety of cell types is advantageous [29] [30].

Adenovirus for CRISPR: Adenovirus can easily package the full SpCas9 and gRNA expression cassette, making it a straightforward tool for CRISPR delivery. It provides high transduction efficiency and very rapid transgene expression. However, its high immunogenicity and transient expression profile make it less suitable for therapeutic applications requiring long-term editing but potentially useful for transient genetic manipulations or in immuno-oncology contexts [31].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Recent studies highlight the performance of these vectors in specific CRISPR applications.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Recent CRISPR Delivery Studies

| Vector / System | CRISPR Application | Model System | Key Performance Metric | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV.CPP.16 | Delivery of CRISPR-Cas13d to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Rdrp gene | Mouse (intranasal) | Prophylaxis against SARS-CoV-2 infection | Significant inhibition of viral gene transcription | [34] |

| Lentivirus (IDLV) | gRNA delivery (with separate Cas9 mRNA) | 293T cells ( in vitro ) | Gene editing efficiency | Highly efficient, but induced significant anti-Cas9 IgG in vivo | [30] |

| Virus-Like Particle (RIDE) | CRISPR RNP delivery for Vegfa knockout | Mouse (subretinal) | Indel frequency in RPE | 38% indel frequency; 43% decrease in choroidal neovascularization area | [30] |

| AAV vs. LNP | General CRISPR modality delivery | N/A | Key differentiators | AAV: Sustained expression, broad tropism. LNP: Transient, good for liver targets. | [32] |

Detailed Experimental Workflows

A critical understanding of viral vector production and transduction protocols is essential for experimental success and data reproducibility.

AAV Vector Production and Purification

The most common method for research-scale AAV production is transient transfection of HEK293 cells using a three-plasmid system [27] [32] [35].

Protocol: AAV Production via HEK293 Transient Transfection

Plasmid Transfection: HEK293 cells (adherent or suspension) are co-transfected with three plasmids:

- Transfer Plasmid: Contains the transgene (e.g., Cas9 or gRNA) flanked by AAV Inverted Terminal Repeats (ITRs).

- Packaging Plasmid: Provides the AAV

repandcapgenes. Thecapgene determines the serotype. - Helper Plasmid: Supplies essential adenoviral genes (E2A, E4, VA RNA) required for AAV replication. Transfection is typically performed using polyethylenimine (PEI) or other commercial reagents [27] [35].

Harvest and Lysis: 48-72 hours post-transfection, cells and media are harvested. The cell pellet is lysed to release the packaged AAV particles.

Purification: The crude lysate is treated with nucleases to degrade unprotected nucleic acids. AAV is then purified using methods such as:

- Ultracentrifugation: Iodixanol density gradient centrifugation is a common research-scale method [27].

- Chromatography: Affinity or ion-exchange chromatography is used for higher purity and is more scalable for manufacturing. This step is critical for removing empty capsids (a key product-related impurity) [32] [35].

Formulation and QC: The purified virus is concentrated and dialyzed into a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS). Rigorous quality control is performed, including:

Diagram 1: AAV production workflow.

Lentiviral Vector Production

Lentiviral vector production also relies on transient transfection of HEK293 cells, typically with a three- or four-plasmid system designed to enhance safety by minimizing the chance of generating replication-competent viruses [27] [29].

Protocol: Third-Generation Lentivirus Production

Plasmid Transfection: HEK293T cells are co-transfected with:

- Transfer Plasmid: Contains the gene of interest (e.g., all-in-one CRISPR construct) flanked by Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs).

- Packaging Plasmid(s): Provides the gag-pol genes (structural proteins and enzymes). In third-generation systems, the

revgene is often on a separate plasmid. - Envelope Plasmid: Encodes the heterologous envelope glycoprotein, most commonly VSV-G, which confers broad tropism [27] [29].

Vector Harvest: Viral supernatant is collected 48 and 72 hours post-transfection, filtered to remove cell debris, and often concentrated via ultracentrifugation or tangential flow filtration.

Titering and QC: Functional titer is determined by transducing target cells and measuring transgene expression (e.g., by flow cytometry for a fluorescent marker) or by qPCR for vector copies integrated into the genome.

Diagram 2: Lentivirus production workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful viral vector production and CRISPR application depend on key reagents and cell lines.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Viral Vector & CRISPR Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Workflow | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HEK293T Cells | Producer cell line for AAV and LV | Readily transfectable, derived from human embryonic kidney cells; "T" denotes expression of SV40 Large T-antigen [35]. |

| Packaging Plasmids | Provide essential viral genes in trans | AAV: Rep/Cap and Helper plasmids. LV: 2nd/3rd gen gag-pol, rev, VSV-G plasmids. Critical for safety and yield [27]. |

| Transfer Plasmid | Carries the therapeutic/editing cargo | Contains ITRs (for AAV) or LTRs (for LV) flanking the expression cassette for Cas9, gRNA, or a reporter gene [27] [32]. |

| Transfection Reagent | Introduces plasmids into producer cells | Polyethylenimine (PEI) is widely used due to its cost-effectiveness and efficiency with HEK293 cells [35]. |

| Purification Resins/Medium | Isolation and purification of viral vectors | Iodixanol for gradient ultracentrifugation; affinity resins (e.g., AVB Sepharose for AAV) for chromatography [27] [35]. |

| Target Cells/Animal Models | For functional validation of vectors | Primary cells or cell lines; disease-specific animal models (e.g., mouse models of IPF [34] or Huntington's disease [30]). |

| Titer & QC Assays | Quantification and quality assessment | qPCR (genome titer), TCID50 or flow cytometry (functional titer), SDS-PAGE/Western (purity), ELISA (empty/full capsids) [32] [35]. |

AAV, Lentivirus, and Adenovirus each occupy a distinct niche in the CRISPR delivery landscape. AAV is the vector of choice for direct in vivo gene editing applications requiring long-term expression in non-dividing cells, despite its packaging constraints. Lentivirus excels in ex vivo cell engineering and applications where stable genomic integration is beneficial. Adenovirus offers high transduction efficiency and large cargo capacity but is limited by immunogenicity. The choice of vector is not one-size-fits-all and must be tailored to the specific experimental or therapeutic goal, considering the trade-offs between payload size, persistence of expression, immunogenicity, and tropism. Emerging technologies like engineered virus-like particles (VLPs) for transient RNP delivery are showing promise in addressing limitations of current viral vectors, such as pre-existing immunity and long-term nuclease expression [30]. As the field advances, continued optimization of production workflows to increase yield and purity, coupled with sophisticated capsid and envelope engineering for precise targeting, will further solidify the role of viral vectors in enabling the next generation of CRISPR therapeutics.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized biomedical research and therapeutic development, offering unprecedented precision in manipulating genetic material. However, the clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapies faces a significant bottleneck: the efficient and safe delivery of genome-editing components into target cells [24]. Delivery vectors are broadly categorized into viral and non-viral systems. While viral vectors, such as adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), offer high transduction efficiency, they present considerable challenges, including immunogenicity, limited packaging capacity, and potential for insertional mutagenesis [36] [15]. These limitations have accelerated the development of non-viral delivery platforms, which offer improved safety profiles, larger payload capacity, and reduced risk of off-target effects [24] [17].

Among the diverse non-viral strategies, three platforms have emerged as frontrunners: Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation, and Polymeric Nanocarriers. These "non-viral champions" are distinguished by their unique mechanisms, applications, and performance characteristics. LNPs, validated by their successful deployment in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, excel in in vivo delivery [37]. Electroporation, a physical method, achieves high efficiency in ex vivo settings, notably in approved therapies like Casgevy for sickle cell disease [18]. Polymeric Nanocarriers, with their highly tunable chemical structures, offer versatile nucleic acid condensation and potential for sophisticated functionalization [36] [2]. This guide provides a objective, data-driven comparison of these three leading non-viral delivery systems, framing their performance within the critical context of viral versus non-viral delivery efficiency for CRISPR therapeutics.

Performance Comparison of Non-Viral Delivery Systems

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and quantitative performance metrics of the three champion non-viral delivery systems, based on current literature and experimental data.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Applications

| Delivery System | Primary Mechanism | Best Suited Application | CRISPR Cargo Format | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Encapsulation and fusion with cell membranes [37] | In vivo delivery (e.g., systemic IV injection) [18] | mRNA, RNP [17] | Proven clinical success; innate liver tropism; suitable for redosing [18] |

| Electroporation | Electrical pulses create transient pores in cell membrane [17] | Ex vivo delivery (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells) [18] | RNP, mRNA [17] | High efficiency for hard-to-transfect cells; direct cytoplasmic delivery [17] |

| Polymeric Nanocarriers | Electrostatic condensation into "polyplexes" [36] [2] | In vitro and in vivo delivery (under development) | DNA, RNP, mRNA [2] | Highly tunable structure; high buffering capacity for endosomal escape [36] [2] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Experimental Studies

| Delivery System | Reported Editing Efficiency | Cell Viability Post-Delivery | Throughput / Scalability | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | ~90% protein reduction in hATTR trial [18] | Mild to moderate infusion-related reactions [18] | High scalability for clinical manufacturing [38] | Endosomal entrapment; limited targeting beyond liver [17] |

| Electroporation | High efficiency in clinical ex vivo editing [18] | Significant cytotoxicity if parameters not optimized [17] | Lower throughput, more suited for ex vivo use [17] | High cell mortality; requires specialized equipment [17] |

| Polymeric Nanocarriers | >40% genomic deletion in RDEB keratinocytes with RNP [2] | Viability maintained >80% with optimized HPAE-EB polymer [2] | Facile synthesis, but batch-to-batch variation can occur [38] | Can struggle with complexation stability and payload release [38] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical resource, this section outlines standard experimental protocols for evaluating each of the three non-viral champion systems.

Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Formulation and Testing

Objective: To formulate LNPs encapsulating CRISPR-RNP and evaluate their editing efficiency in vitro.

- Step 1: LNP Formulation. Prepare lipid mixtures typically containing an ionizable cationic lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol [37]. The ionizable lipid is crucial for endosomal escape [37]. Mix the lipid solution with an aqueous buffer containing the CRISPR-RNP complex using rapid mixing techniques, such as microfluidics, to form uniform LNPs ~100 nm in size [38].

- Step 2: Characterization. Dilute the formed LNPs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to measure particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential. Determine encapsulation efficiency using a Ribogreen assay [37].

- Step 3: In Vitro Transfection. Seed target cells (e.g., HEK293 or hepatocytes) in a 24-well plate. Add LNP formulations at various lipid-to-RNP weight ratios. Incubate for 48-72 hours [24].

- Step 4: Efficacy and Safety Assessment. Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA. Assess editing efficiency via T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing. Evaluate cell viability using a colorimetric assay (e.g., MTT or Alamar Blue) [2].

LNP Experimental Workflow: The process for formulating and testing Lipid Nanoparticles.

Electroporation Protocol for Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery

Objective: To deliver CRISPR-RNP complexes into cells ex vivo using electroporation for high-efficiency genome editing.

- Step 1: RNP Complex Formation. Reconstitute purified Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNA. To form the RNP complex, incubate Cas9 with sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:6.6 (Cas9:sgRNA) for 10-20 minutes at room temperature [2].

- Step 2: Cell Preparation. Harvest the target cells (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells or T-cells) and wash with an electroporation buffer. Resuspend the cells at a high concentration (e.g., 10-20 million cells per mL) [17].

- Step 3: Electroporation. Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex. Transfer the mixture to an electroporation cuvette. Apply an optimized electrical pulse using a specialized electroporator (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector). The specific program (pulse voltage, length, and number) must be empirically determined for each cell type [17].

- Step 4: Post-Transfection Recovery. Immediately after electroporation, add pre-warmed culture medium and transfer the cells to a culture plate. Incubate the cells for 48-72 hours before analyzing editing efficiency and viability [17].

Polymeric Nanocarrier Polyplex Formation and Transfection

Objective: To form polyplexes using a cationic polymer for the delivery of CRISPR plasmid DNA and assess transfection performance.

- Step 1: Polymer Synthesis and Preparation. Synthesize cationic polymers like Highly Branched Poly(beta-amino ester) (HPAE-EB) as described in the literature [2]. Dissolve the polymer in sodium acetate buffer (25 mM, pH 5.2) [2].

- Step 2: Polyplex Formation. Dilute the CRISPR cargo (e.g., plasmid DNA encoding Cas9 and gRNA) in the same sodium acetate buffer. Mix the polymer and DNA solutions at a 1:1 volume ratio at pre-optimized weight/weight (w/w) ratios. Vortex the mixture for 30 seconds and incubate at room temperature for 10-30 minutes to allow polyplex formation [2].

- Step 3: Biophysical Characterization. Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the polyplexes using DLS. Confirm complexation and nucleic acid protection via gel electrophoresis retardation assay [2].

- Step 4: Cell Transfection and Analysis. Add the polyplexes to cells (e.g., HEK293 or primary keratinocytes) at 60-70% confluence. Replace the medium after 4 hours. After 48 hours, analyze transfection efficiency (e.g., via GFP expression if using a reporter plasmid) and gene editing efficacy (via T7E1 assay). Evaluate cell viability 48 hours post-transfection [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of non-viral CRISPR delivery requires a suite of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Non-Viral CRISPR Delivery Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 RNP | The active editing machinery; pre-complexing reduces off-target effects [2] | HiFi Cas9 Nuclease; custom synthetic sgRNA or crRNA+tracrRNA [2] |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids | Core component of LNPs; enables nucleic acid complexation and endosomal escape [37] | DLin-MC3-DMA; SM-102; ALC-0315 [37] |

| Cationic Polymers | Condense nucleic acids via electrostatic interactions to form polyplexes [36] [2] | Highly Branched Poly(β-amino ester) (HPAE-EB); Polyethylenimine (PEI) [36] [2] |

| Helper Lipids | Stabilize LNP structure and enhance performance [37] | Cholesterol (stability); DSPC (structural lipid); PEG-lipids (reduce opsonization) [37] |

| Electroporation Buffer | Environment for cells during electrical pulse; formulation is critical for viability [17] | Cell-type specific buffers; often proprietary to instrument manufacturers [17] |

| Sodium Acetate Buffer | Diluent for polymer and DNA for polyplex formation; optimal at pH ~5.2 [2] | 25 mM concentration is commonly used [2] |

The landscape of CRISPR delivery is no longer dominated solely by viral vectors. Lipid Nanoparticles, Electroporation, and Polymeric Nanocarriers have each demonstrated champion-level capabilities in specific domains. LNPs are the leading platform for in vivo therapeutic delivery, as evidenced by clinical trials. Electroporation remains the gold standard for high-efficiency ex vivo editing of challenging primary cells. Polymeric Nanocarriers offer a highly customizable and promising alternative, with ongoing research focused on improving their efficacy and specificity.

The choice between these systems is not a matter of identifying a single winner, but of matching the tool to the task. Researchers must consider the target cells (in vivo vs. ex vivo), the desired editing window (transient vs. sustained), and the specific cargo (DNA, mRNA, or RNP) when selecting a delivery platform. As these non-viral technologies continue to mature and converge—for instance, in the development of hybrid lipid-polymer systems—their collective potential to unlock the full therapeutic promise of CRISPR gene editing will only expand.

The therapeutic application of CRISPR gene editing is primarily advanced through two distinct delivery paradigms: ex vivo and in vivo editing. The fundamental distinction lies in the site where genetic modification occurs. Ex vivo editing involves harvesting cells from a patient, genetically modifying them outside the body using CRISPR, and then reinfusing the edited cells back into the patient [39]. In contrast, in vivo editing entails the direct administration of the CRISPR therapeutic agent (e.g., viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles) into the patient's body to edit the DNA of target cells in situ [39] [40].

The choice between these paradigms is a cornerstone of therapeutic design and is intrinsically linked to the broader thesis on viral versus non-viral delivery vector efficiency. This guide provides an objective comparison of these workflows, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Ex Vivo Gene Editing: The CASGEVY Model

Clinical Workflow and Protocol

Ex vivo CRISPR therapy, exemplified by Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), involves a multi-step, centralized process [39]. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages from cell collection to patient reinfusion.

The clinical protocol for Casgevy, as established in the CLIMB-111, CLIMB-121, and CLIMB-131 trials, involves [39]:

- HSC Collection & Shipment: CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are collected from the patient via apheresis and shipped to a specialized manufacturing facility.

- CRISPR-Cas9 Editing: At the facility, cells are electroporated with CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes targeting the BCL11A gene to disrupt its expression and induce fetal hemoglobin production.

- Patient Conditioning: While cells are being edited, the patient undergoes myeloablative conditioning with busulfan to clear bone marrow space for the edited cells.

- Reinfusion: The CRISPR-edited CD34+ cells are infused back into the patient.

- Engraftment: The edited cells engraft in the bone marrow and begin producing red blood cells with elevated fetal hemoglobin levels.

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Ex Vivo CRISPR Workflows

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR RNP Complex | The active editing machinery; Cas9 protein pre-complexed with sgRNA. | High-fidelity Cas9 (e.g., SpyFi Cas9) and sgRNA targeting the gene of interest (e.g., BCL11A). |

| CD34+ Cell Isolation Kit | To purify hematopoietic stem cells from apheresis product. | Immunomagnetic bead-based separation (e.g., CliniMACS system). |

| Electroporation System | Physical method to deliver RNP complexes into hard-to-transfect HSCs. | Neon Transfection System or Lonza 4D-Nucleofector. |

| Stem Cell Culture Media | Supports viability and potency of HSCs during the editing process. | Serum-free media supplemented with cytokines (e.g., SCF, TPO, FLT3-L). |

In Vivo Gene Editing: The Lipid Nanopipeline

Clinical Workflow and Mechanism of Action

In vivo editing simplifies the clinical pathway for the patient by directly administering the CRISPR therapy. The mechanism relies on sophisticated delivery vectors to reach and edit specific cells inside the body. The process for a systemically administered LNP-based therapy is detailed below.

A representative protocol from an ongoing clinical trial for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) using Intellia Therapeutics' NTLA-2001 illustrates this paradigm [18]:

- Formulation: The CRISPR payload, consisting of mRNA for the Cas9 protein and a guide RNA targeting the TTR gene, is encapsulated in liver-tropic lipid nanoparticles (LNPs).

- Administration: A single dose of the LNP formulation is administered to the patient via intravenous infusion.

- In Vivo Action: LNPs naturally accumulate in liver cells (hepatocytes), release their payload, and the Cas9 protein is expressed. The resulting Cas9-gRNA complex enters the nucleus and creates a double-strand break in the TTR gene, knocking it out and reducing the production of the disease-causing protein.

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for In Vivo CRISPR Workflows

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Critical component of LNPs; enables encapsulation, endosomal escape, and payload release. | Proprietary lipids like ALC-0315 or SM-102; SORT molecules for targeted organ delivery. |

| CRISPR mRNA & sgRNA | The genetic blueprint for the editing machinery. | Modified nucleotides for stability; codon-optimized Cas9 mRNA and target-specific sgRNA. |

| LNP Formulation System | For consistent, scalable production of CRISPR-loaded nanoparticles. | Microfluidic mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr). |

| Animal Disease Models | For pre-clinical efficacy and safety testing of the in vivo therapy. | Transgenic mouse or non-human primate models of the target disease. |

Direct Comparison: Workflows, Efficiencies, and Applications

Quantitative Comparison of Paradigms

Table 3: Head-to-Head Comparison of Ex Vivo vs. In Vivo Delivery Paradigms

| Parameter | Ex Vivo (Casgevy model) | In Vivo (LNP model) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Workflow | Complex, multi-step; requires cell harvesting, manufacturing, and reinfusion. | Simplified; single intravenous infusion. |

| Manufacturing | Decentralized, patient-specific (autologous), logistically complex. | Centralized, off-the-shelf (allogeneic), scalable. |

| Delivery Control | High; editing occurs in a controlled, validated process outside the body. | Lower; dependent on biodistribution and uptake of the delivery vector. |

| Target Tissues | Limited to cells that can be extracted, manipulated, and reinfused (e.g., hematopoietic cells, T-cells). | Broad potential, but currently most efficient for liver (with LNPs) and muscle (with AAVs). |

| Therapeutic Examples | Casgevy: Sickle Cell Disease, Beta-Thalassemia [39]. CAR-T-cell therapies: Cancer immunotherapy [39]. | NTLA-2001 (Intellia): hATTR Amyloidosis, Hereditary Angioedema (HAE) [18]. CTX310/320 (CRISPR Tx): Cardiovascular disease [40]. |

| Key Delivery Vectors | Physical Methods: Electroporation (primary method for RNP delivery) [17]. Viral Vectors: Lentivirus for certain cell engineering applications. | Non-Viral: Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) for mRNA/sgRNA [41] [18]. Viral Vectors: Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) for DNA templates. |

| Immunogenicity | Lower risk of immune reaction to CRISPR components due to transient RNP exposure. | Higher concern, especially with viral vectors (AAV); pre-existing immunity is a challenge. LNPs allow for potential re-dosing [18]. |

| Editing Specificity | Potentially higher; controlled conditions and transient RNP delivery reduce off-target risks [17]. | Varies with delivery; prolonged expression from viral vectors may increase off-target risk. |

| Regulatory Status | Clinically proven; first FDA/EMA-approved CRISPR therapy (Casgevy) [39]. | Late-stage clinical trials; no approved therapies yet, but promising Phase I/II data [40] [18]. |

Supporting Experimental Data and Outcomes

- Ex Vivo Efficacy: In the pivotal trials for Casgevy, patients with sickle cell disease experienced a resolution of vaso-occlusive crises. Of 44 patients with at least 16 months of follow-up, over 95% achieved this primary endpoint [39]. Patients with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia saw 93% (54 of 58 patients) achieve transfusion independence [39].