X-ray Crystallography vs. Cryo-EM: A Strategic Guide for Complex Structure Analysis

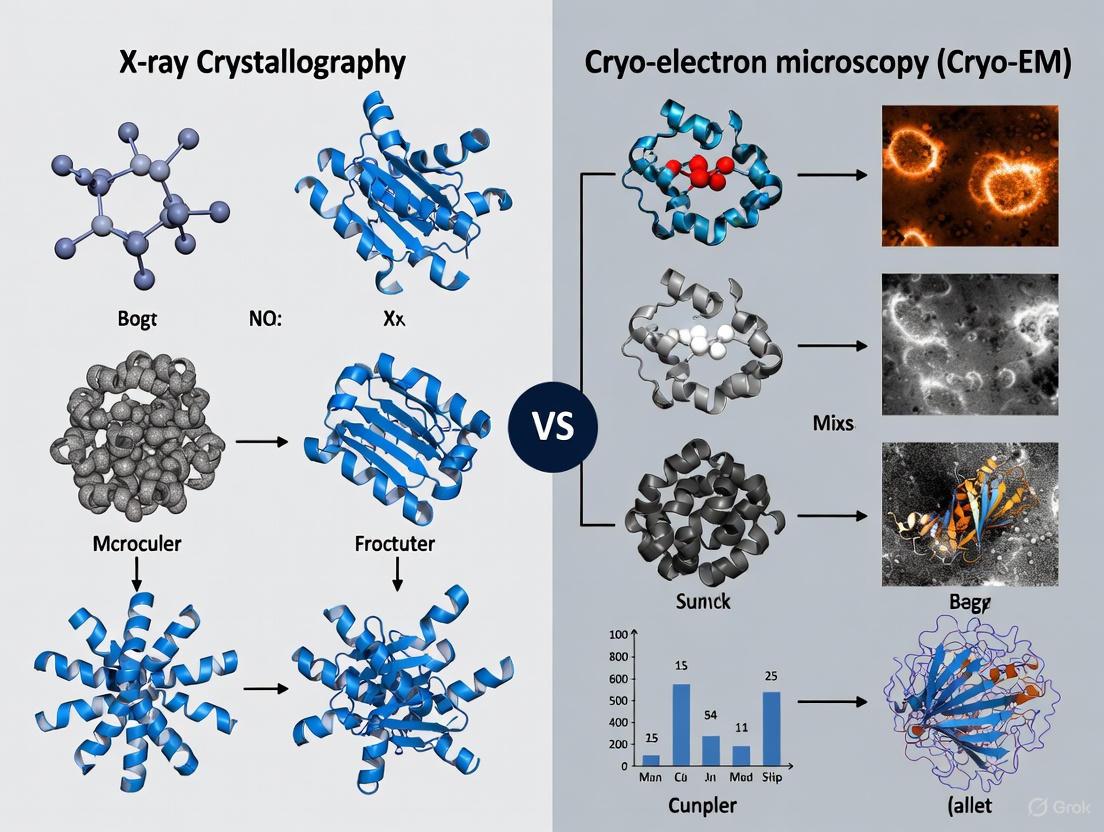

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for determining the structures of complex biological macromolecules.

X-ray Crystallography vs. Cryo-EM: A Strategic Guide for Complex Structure Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for determining the structures of complex biological macromolecules. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and practical applications of each technique. We offer a strategic framework for selecting and optimizing the appropriate method based on sample properties and research goals, incorporating the latest advancements and complementary approaches. The content also addresses troubleshooting common challenges, validates structural models, and discusses the transformative impact of integrating these methods with AI to accelerate biomedical discovery.

Understanding the Core Principles: How X-ray Crystallography and Cryo-EM Work

The Historical Dominance and Physical Basis of X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography has long been the cornerstone of structural biology, providing the foundational framework for understanding the three-dimensional architecture of biological macromolecules. Despite the recent rise of powerful techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), X-ray crystallography remains an indispensable tool in the structural biologist's toolkit, particularly for obtaining high-resolution structures of proteins and complexes crucial for drug discovery and mechanistic studies [1] [2]. Its historical dominance is reflected in database statistics, with over 86% of the structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) having been solved by this method [2].

The technique's preeminence stems from its robust physical basis in X-ray diffraction and its ability to deliver atomic-resolution structures that reveal intricate details of molecular interactions. This article examines the fundamental principles underpinning X-ray crystallography, compares its capabilities with cryo-EM through experimental data, and explores recent methodological advancements that continue to enhance its applicability to challenging biological problems.

Physical and Historical Foundations

Basic Theory and Principles

X-ray crystallography relies on the diffraction of X-rays by the electron clouds of atoms within a crystalline lattice [2]. When a crystal is exposed to a collimated X-ray beam, the rays interact with electrons in the crystal, producing constructive and destructive interference patterns that can be recorded on a detector [3] [2]. These diffraction patterns contain information about the electron density within the crystal.

The mathematical foundation of X-ray crystallography is described by Bragg's Law: nλ = 2d sinϑ, where λ represents the wavelength of the incident X-rays, d is the distance between crystal planes, ϑ is the angle of incidence, and n is an integer [2]. This relationship defines the conditions for constructive interference and enables researchers to calculate atomic positions from diffraction data.

Historical Context and Dominance

The technique has its origins in the early 20th century, beginning with Max von Laue's demonstration of X-ray diffraction by crystals in 1912 and the subsequent development of X-ray crystallography as an analytical method by Sir William Henry Bragg and his son Sir William Lawrence Bragg, who earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915 for their work [2]. The method was later extended to biological molecules, most famously leading to the determination of the DNA double helix structure by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953 using X-ray diffraction data from Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins [2].

Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, X-ray crystallography became the dominant technique in structural biology due to its ability to provide precise atomic-level information. According to recent PDB statistics, X-ray crystallography still accounts for approximately 66% of all structures released annually, though this represents a decline from previous years as cryo-EM usage has increased [2].

Table 1: Annual Structure Deposition by Technique (2023)

| Technique | Number of Structures | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | 9,601 | 66% |

| Cryo-EM | 4,579 | 31.7% |

| NMR | 272 | 1.9% |

| Multiple Methods | Others | <1% |

Technical Comparison with Cryo-EM

Resolution and Data Quality Metrics

Both X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM utilize Fourier transforms to calculate experimental maps, but they differ significantly in how resolution is defined and determined [3]. In X-ray crystallography, resolution is typically truncated by the user during data processing based on statistical parameters, with the effective resolution providing a more descriptive measure that accounts for anisotropy and data incompleteness [3].

For cryo-EM, the most widely accepted resolution metric is the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) using a threshold of 0.143, though this remains debated within the field [3]. Importantly, the resolution obtained from FSC represents an estimate of varying resolution across different regions of the density map.

Table 2: Resolution Comparison Between Techniques

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Single-Particle Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Current Resolution Record | 0.48 Å [3] | 1.54 Å [3] |

| Typical Resolution Range | 1.5-3.0 Å | 2.5-4.0 Å |

| Key Resolution Metric | Signal-to-noise ratio ([3]<="" td="" σ(i)>),=""> | Fourier shell correlation (FSC) [3] |

| Common Cutoff Criteria | CC1/2 > 0.3 [3] | FSC > 0.143 [3] |

Sample Requirements and Limitations

A fundamental distinction between the techniques lies in their sample requirements. X-ray crystallography demands high-quality crystals of sufficient size, which remains a significant bottleneck for many biological targets [1]. The crystallization process can be particularly challenging for membrane proteins, flexible complexes, and dynamic assemblies [4].

In contrast, cryo-EM requires only a thin layer of vitreous ice containing the purified particles, bypassing the crystallization hurdle entirely [4] [5]. This advantage has made cryo-EM particularly valuable for studying large macromolecular complexes that resist crystallization. However, cryo-EM faces its own challenges with preferred particle orientation, where proteins adsorb to the air-water interface in limited orientations, potentially compromising reconstruction quality [6].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

X-ray Crystallography Workflow

The process of structure determination by X-ray crystallography follows a well-established sequence [2]:

Diagram 1: X-ray Crystallography Workflow

Crystallization represents a critical and often rate-limiting step, requiring extensive screening and optimization to obtain crystals of suitable quality and size [2]. Recent innovations include the use of electric fields during crystallization, which has been shown to produce higher-quality crystals in some cases [7].

Data collection at synchrotron facilities involves exposing crystals to high-intensity X-ray beams and recording diffraction patterns [8] [2]. Fourth-generation synchrotrons like the ESRF-EBS have revolutionized this process with serial microsecond crystallography (SµX), which uses microsecond X-ray pulses to collect data from microcrystals at room temperature, enabling time-resolved studies of dynamic processes [8].

Phasing remains a central challenge, as the phase information is lost in the diffraction experiment and must be recovered through methods like molecular replacement (using a known homologous structure) or experimental phasing (using anomalous scatterers) [2].

Cryo-EM Single-Particle Analysis Workflow

The cryo-EM workflow differs substantially, emphasizing sample vitrification and computational processing [9] [5]:

Diagram 2: Cryo-EM Single-Particle Workflow

Recent advances in machine learning have significantly automated the model-building process in cryo-EM. Tools like ModelAngelo combine information from cryo-EM maps with protein sequence and structural information in a graph neural network to build atomic models comparable in quality to those generated by human experts [9].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screens | Sparse matrix screening to identify initial crystallization conditions | Commercial screens (Hampton Research, Qiagen) with various precipants, salts, and buffers |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Materials | Membrane protein crystallization in lipidic environment | Monolein for GPCR crystallization [4] |

| Cryoprotectants | Protect crystals during cryo-cooling | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, various commercial solutions |

| Anomalous Scatterers | Experimental phasing via MAD/SAD | Selenium (selenomethionine), halides, heavy metals [2] |

| High-Viscosity Extruders (HVE) | Sample delivery for serial crystallography | Syringe-based injectors for microcrystal delivery [8] |

| Fixed-Target Sample Supports | Sample presentation for serial data collection | Silicon chips, kapton foils with micro-wells [8] |

| Direct Electron Detectors | High-resolution data collection in cryo-EM | Modern cameras for single-particle analysis [4] |

Recent Advancements and Future Perspectives

Technological Innovations in X-ray Crystallography

The field continues to evolve with significant methodological advancements. Serial crystallography approaches, both at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and now at fourth-generation synchrotrons, have enabled data collection from microcrystals at room temperature, providing insights into physiological conformations and enabling time-resolved studies [8].

The recent development of serial microsecond crystallography (SµX) at beamlines like ID29 at the ESRF-EBS represents a quantum leap forward. This approach combines microsecond exposure times with innovative beam characteristics and adaptable sample environments to produce high-quality data from minimal crystalline material [8]. Applications to integral membrane receptors have demonstrated that only a few thousand diffraction images can yield fully interpretable electron density maps, as shown in studies of the antagonist istradefylline-bound A2A receptor conformation [8].

External physical stimuli such as electric fields are being explored for post-crystallization resolution enhancement. Recent research has demonstrated that applying high-voltage electric fields (2-11 kV/cm) to mounted crystals can improve diffraction quality progressively with exposure time, potentially offering a pathway to enhance resolution for challenging projects [7].

Integration with Computational Methods

The intersection of experimental structural biology with artificial intelligence represents a transformative development. While tools like AlphaFold have revolutionized protein structure prediction, they complement rather than replace experimental methods like X-ray crystallography [4] [5]. In fact, the integration of AI-based model building with experimental data is creating powerful hybrid approaches.

For both X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, machine learning tools are increasingly being deployed to address specific challenges. The MIC (Metric Ion Classification) tool uses deep learning to assign identities to water molecules and ions in experimental maps, a task that can be challenging based on density alone [10]. By using interaction fingerprints and metric learning, MIC achieves superior accuracy in classifying water/ion sites compared to existing empirical methods [10].

X-ray crystallography maintains its vital role in structural biology despite the impressive ascent of cryo-EM, with each technique offering complementary strengths. The historical dominance of crystallography rests on its robust physical foundation, capacity for atomic-resolution structure determination, and continuous technological innovation. Recent developments in serial crystallography, time-resolved studies, and integration with computational methods ensure that X-ray crystallography will remain an essential tool for elucidating biological mechanisms and guiding drug discovery efforts for the foreseeable future.

The optimal choice between techniques depends on the specific biological question, sample properties, and desired information. For many applications, particularly those requiring the highest possible resolution or dynamic information, these methods are increasingly used in concert rather than competition, providing multidimensional insights into structure-function relationships in biological systems.

The "Resolution Revolution" in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) represents a paradigm shift in structural biology, fundamentally altering how scientists visualize biological macromolecules. This transformation, propelled by groundbreaking technical advances, has enabled researchers to determine high-resolution structures of complex biological targets that were previously intractable [11] [12]. The revolution has positioned cryo-EM as a powerful complement and, in many cases, a viable alternative to the long-dominant technique of X-ray crystallography, particularly for studying large, dynamic, and membrane-embedded complexes [13] [14]. This guide objectively compares the performance of cryo-EM against X-ray crystallography, providing the experimental data and methodological context that researchers and drug development professionals need to select the optimal technique for their structural studies on complex biological systems.

Fundamental Principles and Technological Leaps

Core Theory of Single-Particle Cryo-EM

The fundamental theory of cryo-EM rests on visualizing biological samples preserved in their native state. The technique involves flash-freezing a purified sample solution in thin vitreous ice, a process called vitrification. This rapid cooling prevents water molecules from forming crystalline ice, instead trapping them in an amorphous, glass-like state that preserves the native structure of the embedded molecules [15] [16]. These vitrified samples are then imaged in an electron microscope under cryogenic conditions, where an electron beam passes through the specimen, and a detector records two-dimensional (2D) projection images [16]. Since the molecules are randomly oriented in the ice, the collected 2D images represent the same structure viewed from different angles. Advanced computational algorithms then align and classify hundreds of thousands—or even millions—of these particle images to reconstruct a high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) structure [15] [12].

The Engine of the Revolution: Key Technological Advances

The "Resolution Revolution," which gained full momentum around 2014, was not triggered by a single discovery but by convergent advancements across several fronts [17] [12].

- Direct Electron Detectors (DEDs): The adoption of DEDs was arguably the most crucial advancement. These detectors replaced traditional film and CCD cameras, offering dramatically improved sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio. Their fast readout rates enable movie-mode data collection, allowing for the correction of beam-induced motion during exposure, which was a major limitation to achieving high resolution [4] [12].

- Advanced Image Processing Software: The development of powerful, reliable algorithms based on maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches allowed for optimal extraction of structural information from noisy images [12]. These software suites, often capable of automated operation, include robust classification schemes that can separate different structural states within a single sample [12].

- Sample Preparation and Vitrification: Standardized methods for preparing thin, homogeneous vitreous ice layers have been critical. Automated vitrification devices (plungers) now enable reproducible sample freezing, which is essential for high-quality data collection [16].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a single-particle cryo-EM experiment, from sample preparation to 3D reconstruction:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cryo-EM Experimental Workflow

The journey to a high-resolution structure via single-particle cryo-EM involves a multi-stage process, each with its own critical protocols:

- Sample Preparation and Vitrification: A purified protein or complex solution (typically 0.1-0.2 mg) is applied to an EM grid coated with a holey carbon film. Excess liquid is blotted away, leaving a thin film suspended across the holes. The grid is then rapidly plunged into a cryogen (like liquid ethane) cooled by liquid nitrogen. This vitrification process occurs within milliseconds, preserving the molecules in a near-native, hydrated state [16].

- Data Collection: The vitrified grid is loaded into a cryo-electron microscope maintained at liquid nitrogen temperatures. Using a low-dose electron beam to minimize radiation damage, the microscope records thousands of "micrographs" as movie stacks. Each micrograph contains images of dozens to thousands of individual particles in random orientations [16] [12].

- Image Processing: The movie stacks are first processed for motion correction and exposure weighting to create a sharp, averaged micrograph [12]. Subsequent steps include:

- Particle Picking: Automated algorithms identify and extract the individual particle images from the micrographs.

- 2D Classification: Extracted particles are classified into groups representing similar views, averaging out noise and allowing for the removal of non-particle contaminants or damaged particles.

- Initial Model Generation: An initial low-resolution 3D model is created using various algorithms.

- 3D Classification and Refinement: Particles are subjected to multiple rounds of 3D classification to isolate structurally homogeneous subsets. A final, homogeneous set of particles is then used for high-resolution 3D refinement, resulting in a final 3D density map [15] [12].

- Model Building and Validation: An atomic model is built into the resolved electron density map. The model is iteratively refined against the map, and its quality is validated using various metrics to ensure accuracy and avoid overfitting [12].

X-ray Crystallography Workflow

For a meaningful comparison, it is essential to understand the workflow of the primary alternative technique:

- Crystallization: The purified protein (typically >2 mg) is subjected to a vast screen of chemical conditions to induce the formation of well-ordered, three-dimensional crystals. This is often the most significant bottleneck and can take weeks to months [13] [18].

- Data Collection: A single crystal is harvested and exposed to a high-intensity X-ray beam, usually at a synchrotron source. The crystal diffracts the X-rays, producing a pattern of spots on a detector [18].

- Data Processing and Phasing: The diffraction patterns are processed to determine the amplitude of the diffracted waves. A critical challenge is solving the "phase problem," as the phase information is lost during measurement. Phasing is typically done by molecular replacement (using a similar known structure) or experimental methods like soaking crystals in heavy atom solutions [15] [18].

- Model Building and Refinement: An electron density map is calculated using the phases and amplitudes. An atomic model is built into this map and refined against the diffraction data to improve its fit and geometry [18].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The selection between cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography is guided by the specific properties of the biological sample and the goals of the research project. The following tables provide a structured, data-driven comparison.

Sample-Based Method Selection

| Property | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Optimal >100 kDa [13] | Optimal <100 kDa [13] |

| Structural Stability | Flexible/Dynamic acceptable [13] | Requires rigid structure [13] |

| Sample Amount | 0.1-0.2 mg [13] | >2 mg typically [13] |

| Sample Purity | Moderate heterogeneity acceptable [13] | High homogeneity required [13] |

| Protein Type | Ideal for membrane proteins & complexes [11] [13] | Best for soluble proteins [13] |

Technical and Operational Considerations

| Factor | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | 2.5-4.0 Å [13] | 1.5-2.5 Å [13] |

| Maximum Resolution | 2-3 Å [13] | Sub-1 Å possible [13] |

| Timeline | Weeks typically [13] | Weeks to months [13] |

| Data Collection | Hours to days [13] | Minutes to hours [13] |

| Sample Preparation | Vitrification optimization [13] [16] | Crystal growth & optimization [13] [18] |

| Equipment Access | High-end electron microscope [13] | Synchrotron access required [13] |

Application-Based Strengths and Limitations

| Application | Cryo-EM Advantages | X-ray Crystallography Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Protein Analysis | Preserves native lipid environment; minimizes denaturation; captures conformational states [11] [13] | Higher resolution for stable constructs; well-established for small membrane proteins [13] |

| Large Complex Studies | No size limitations; maintains quaternary structure; reveals assembly mechanisms [13] [14] | High resolution for stable subcomplexes; detailed interface analysis [13] |

| Dynamic Structure Visualization | Captures conformational ensembles; reveals transition states; maintains solution-state dynamics [13] [17] | Atomic details of discrete states; high-resolution ligand binding studies [13] |

| Drug Discovery | Visualization of drug binding on challenging targets (e.g., GPCRs, ion channels) [11] | Ultra-high resolution ligand binding; established fragment screening pipelines [13] [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of cryo-EM experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and equipment.

| Item | Function in Cryo-EM |

|---|---|

| Holey Carbon Grids | EM support grids with a perforated carbon film; the sample is suspended across the holes for imaging [16]. |

| Cryogen (Liquid Ethane) | Used for rapid vitrification of the sample. Its high heat capacity enables the ultrafast cooling needed to form amorphous ice [16]. |

| Direct Electron Detector | The core hardware responsible for the resolution revolution. It directly detects electrons with high sensitivity and speed, enabling motion correction [4] [12]. |

| Cryo-EM Microscope | A high-end transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with a cryo-stage to keep the sample at cryogenic temperatures (below -150°C) during data collection [16]. |

| Vitrification Device (Plunger) | An automated instrument that standardizes the process of blotting excess sample and plunging the grid into the cryogen [16]. |

The "Resolution Revolution" in cryo-EM has democratized high-resolution structural biology, providing a powerful pathway for determining the structures of complex and dynamic macromolecules that defy crystallization. While X-ray crystallography remains unparalleled for obtaining the highest-resolution structures of well-behaved, crystallizable targets and is deeply integrated into high-throughput drug discovery pipelines, cryo-EM has carved out a dominant niche for studying large complexes, membrane proteins, and functionally relevant conformational states [11] [13] [14].

The choice between these techniques is not a simple declaration of superiority but a strategic decision based on the target's properties and the research question. For researchers and drug developers, the modern structural biology toolkit is most powerful when these techniques are viewed as complementary. The synergistic use of both cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography, often augmented by AI-based prediction tools, provides the most comprehensive understanding of molecular structure and mechanism, ultimately accelerating the pace of biomedical discovery and therapeutic innovation [4].

For decades, X-ray crystallography has stood as the undisputed gold standard for determining high-resolution structures of biological macromolecules, contributing the vast majority of entries in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [19]. However, the early 2010s witnessed a "resolution revolution" in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) that fundamentally transformed structural biology [20]. This technological upheval, recognized by the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, enabled researchers to visualize complex biological structures at near-atomic resolution without requiring crystallization [20]. Rather than competing methodologies, these techniques have emerged as powerfully complementary tools that, when integrated, provide a more holistic view of biological structure and function than either could achieve alone [21]. The synergy between them allows scientists to push the boundaries of what is possible in structural biology, from capturing dynamic processes in real-time to visualizing large macromolecular complexes in their native cellular environments.

Statistical data from the PDB reveals a telling trend: while X-ray crystallography remains dominant, accounting for approximately 66% of structures released in 2023, cryo-EM's contribution has surged from nearly negligible in the early 2000s to over 31% by 2023-2024 [19]. This shift reflects the unique strengths and addressing of historical limitations of both techniques. This guide provides an objective comparison of performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to help researchers and drug development professionals strategically select and integrate these powerful structural biology tools.

Technical Comparison: Fundamental Principles and Capabilities

Core Technical Specifications

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample State | Crystallized biomolecules | Vitrified solution in near-native state |

| Radiation Source | X-ray photons | High-energy electrons |

| Key Detection Principle | Diffraction pattern from crystal lattice | 2D projection images compiled into 3D reconstruction |

| Resolution Range | Atomic-level (typically <2.0 Å) | Near-atomic to atomic (typically 1.8-4.0 Å) |

| Optimal Sample Size | Small molecules to macromolecules (<1000 kDa) | Large complexes (>100 kDa), viruses, organelles |

| Sample Preparation Complexity | High (requires high-quality crystals) | Moderate (requires vitrification and grid preparation) |

| Typical Experiment Duration | Hours to days (after crystallization) | Days to weeks (including grid screening) |

| Dynamic Studies Capability | Limited (requires trapping states) | Limited (but can capture multiple conformations) |

Performance Metrics for Different Sample Types

Table 2: Performance comparison across different biological samples

| Sample Type | X-ray Crystallography Performance | Cryo-EM Performance | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Proteins | Challenging; requires crystallization in detergents or lipid cubic phases [4] | Excellent; particularly suitable for large membrane complexes [22] [4] | TRPML1 ion channel structures with bound modulators [22] [23] |

| Small Proteins (<100 kDa) | Excellent; high resolution typically achieved | Challenging; lower signal-to-noise for small molecules [21] | Lysozyme studies at sub-10ms resolution [24] |

| Large Macromolecular Complexes | Challenging; often difficult to crystallize | Excellent; ideal for ribosomes, viruses, filaments [20] [21] | Ribosome, nuclear pore complex structures [4] |

| Flexible/Dynamic Complexes | Poor; requires trapping conformational states | Good; can often resolve multiple conformations [21] | Transcription complexes studied in native context [25] |

| Ion/Water Identification | Excellent; clear electron density maps | Challenging; difficulty generating meaningful difference maps [10] | MIC tool developed specifically for cryo-EM ion assignment [10] |

Landmark Studies Demonstrating Technical Complementarity

Case Study 1: TRPML1 Ion Channel Investigation

The lysosomal ion channel TRPML1 represents a compelling case study where cryo-EM enabled structural insights that were previously challenging with X-ray crystallography alone. In a landmark 2025 study, researchers applied high-throughput cryo-EM to determine structures of TRPML1 bound to ten chemically diverse modulators, including both agonists and antagonists [22] [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Protein Purification: TRPML1 was expressed and purified using detergent solubilization from membrane fractions.

- Sample Preparation: Purified protein-ligand complexes were applied to cryo-EM grids and vitrified using liquid ethane plunge freezing.

- Data Collection: High-resolution data were collected using Titan Krios microscopes equipped with direct electron detectors.

- Image Processing: Single-particle analysis was performed using advanced algorithms to generate 3D reconstructions.

- Model Building: Atomic models were built and refined into cryo-EM density maps achieving resolutions sufficient to visualize ligand binding poses.

The structural data revealed that agonists and antagonists induced distinct open and closed pore conformations respectively, providing mechanistic understanding of ligand-induced channel regulation [22]. This depth of structural information supports iterative structure-based drug design cycles for this important biological target, demonstrating cryo-EM's transformative potential for integral membrane proteins refractory to X-ray crystallography [23].

Case Study 2: Time-Resolved Lysozyme Study

Recent advancements in mix-and-quench time-resolved X-ray crystallography have demonstrated the unique capabilities of crystallography for capturing rapid enzymatic processes. A 2025 study achieved sub-10 millisecond time resolution in studying N-acetylglucosamine (NAG1) binding to lysozyme [24].

Experimental Protocol:

- Reaction Initiation: Rapid mixing of lysozyme crystals with ligand solution using specialized dispensing systems.

- Thermal Quenching: Reactions were captured at precise time points (8ms to 2s) via ultra-rapid cooling in boiling liquid nitrogen.

- Data Collection: Cryocrystallographic data were collected from single crystals per time point at synchrotron beamlines.

- Structure Determination: Electron density maps revealed the evolution of ligand binding and conformational changes.

This approach yielded structures showing the evolution of ligand binding using only one crystal per time point, highlighting the sample efficiency achievable with modern crystallographic methods [24]. The nominal time resolution of 8ms represents a significant advancement for chemically-initiated reactions, comparable to the best achievements in time-resolved cryo-EM [24].

Integrated Workflows and Technique Selection

Decision Framework for Technique Selection

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting between X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM based on sample characteristics and research objectives:

Diagram 1: Technique selection workflow (Title: Structural Biology Technique Selection)

Synergistic Applications in Drug Discovery

The most powerful structural biology approaches often leverage both techniques in complementary roles:

Cryo-EM Provides Architecture, X-ray Adds Atomic Detail: Cryo-EM can generate initial medium-resolution maps of large complexes, into which high-resolution crystal structures of individual components can be docked [21]. This approach has been particularly valuable for studying dynamic systems that resist crystallization as complete assemblies.

Cryo-EM Assists with Phase Problem in Crystallography: Cryo-EM maps can provide initial models for molecular replacement, helping solve the phase problem that often challenges crystallographic structure determination [21].

Hybrid Methods for Membrane Protein Structural Biology: The combination of techniques is particularly powerful for membrane proteins, where cryo-EM reveals full-length structures in lipid environments while crystallography provides ultra-high-resolution details of binding sites and catalytic centers [22] [4].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and equipment for structural biology studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Lipidic cubic phase matrices | Membrane protein crystallization | X-ray Crystallography |

| Cryo-EM grids (e.g., gold, copper) | Sample support for vitrification | Cryo-EM | |

| Vitrification devices (e.g., plunge freezers) | Rapid freezing for sample preservation | Cryo-EM | |

| Microscopy & Detection | Titan Krios microscope | High-resolution data collection | Cryo-EM |

| Talos Arctica microscope | Screening and data collection | Cryo-EM | |

| Direct electron detectors | Enhanced signal-to-noise ratio | Cryo-EM | |

| Data Processing | MicroED | Electron diffraction from microcrystals | Both |

| MIC (Metric Ion Classification) | Identifies water/ion sites in maps | Both [10] | |

| Serial femtosecond crystallography | Time-resolved studies at XFELs | X-ray Crystallography [24] | |

| Specialized Applications | Time-resolved mixing apparatus | Millisecond reaction initiation | X-ray Crystallography [24] |

| Cryo-focused ion beam mill | Sample thinning for cellular tomography | Cryo-EM [20] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Artificial Intelligence

The field of structural biology is being further transformed by the integration of artificial intelligence with both experimental techniques. AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold 2 and the emerging AlphaFold 3 are being integrated into cryo-EM workflows to expand their impact [4]. Similarly, machine learning tools such as MIC (Metric Ion Classification) leverage deep learning to assign identities to water and ion sites in both cryo-EM and crystal structures, achieving superior accuracy compared to empirical methods [10]. These computational advances are particularly valuable for interpreting limited resolution regions and for understanding the chemical microenvironments surrounding bound ligands and cofactors.

Native Cellular Context with Cryo-Electron Tomography

Cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) represents a powerful extension of cryo-EM that enables 3D visualization of biological structures in their native cellular environments [25]. Unlike traditional structural techniques that require purification and isolation of individual components, cryo-ET can image flash-frozen cells and tissues in toto, preserving the spatial relationships between macromolecular complexes. This capability has been likened to the difference between studying animals in captivity versus observing them in their natural habitat [25]. Researchers are using this technology to visualize previously intractable processes, such as the rapid recycling of synaptic vesicles in neurons, where they observed that a specialized form of the protein dynamin accelerates vesicle creation in human neurons [25].

Pushing Temporal Resolution Boundaries

Both techniques continue to evolve toward capturing biomolecular dynamics with increasingly fine temporal resolution. For cryo-EM, recent advances have enabled nominal time resolutions in the millisecond range, allowing researchers to capture structural states during rapid cellular processes [25] [24]. In crystallography, developments in mix-and-quench approaches and serial femtosecond crystallography at X-ray free-electron lasers have pushed time resolution into the sub-millisecond domain for suitable systems [24]. The ongoing refinement of these time-resolved methods promises to transform structural biology from a primarily static discipline to one capable of producing true molecular "movies" of biological function.

The evolving relationship between X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM exemplifies how methodological advances in structural biology create complementary rather than competing capabilities. While crystallography remains unsurpassed for determining fine atomic details of crystallizable proteins and rapid dynamic processes, cryo-EM has dramatically expanded the scope of accessible targets to include large complexes, flexible assemblies, and membrane proteins. The most innovative structural biology increasingly leverages both techniques in integrated workflows, often augmented by AI-driven computational methods. For researchers and drug development professionals, strategic selection and combination of these approaches based on specific project needs and sample characteristics will continue to yield the most comprehensive insights into structure-function relationships, ultimately accelerating therapeutic discovery and fundamental biological understanding.

For decades, X-ray crystallography has stood as the undisputed gold standard for determining high-resolution structures of biological macromolecules, dominating the entries in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). However, the past several years have witnessed a remarkable shift with the emergence of single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) as a powerful complementary technique. Triggered by what is widely known as the "resolution revolution" in cryo-EM, this method has rapidly grown from a niche technique to a major driver of structural biology, rivaling crystallography in its ability to solve structures at near-atomic resolution [26]. This transformation is not a simple replacement of one technology by another but a realignment of the structural biology ecosystem, where each method's unique strengths are being leveraged to tackle increasingly complex biological questions.

The growing share of cryo-EM in the PDB is a quantifiable trend with profound implications for research strategies, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where structure-based drug design has become a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. This analysis examines the quantitative evidence of this shift, compares the technical and operational characteristics of both techniques, and explores their complementary roles in researching complex biological structures. The data reveals a dynamic and expanding field where cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography together provide a more comprehensive toolkit for elucidating the three-dimensional structures that underpin biological function and therapeutic intervention.

Quantitative Analysis of PDB Deposition Trends

Historical Dominance and Recent Shifts

The distribution of experimental methods used for structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank provides the most direct evidence of cryo-EM's rising prominence. For years, X-ray crystallography accounted for the vast majority of PDB structures. As of September 2024, statistics show that over 86% of all structures ever deposited in the PDB were solved using X-ray methods [27]. This historical dominance reflects crystallography's established workflows, widespread accessibility, and unparalleled track record in delivering atomic-resolution structures for countless proteins and complexes.

However, the annual deposition patterns reveal a dramatic rebalancing. In 2023, X-ray crystallography accounted for approximately 66% (9,601) of newly released structures, while cryo-EM accounted for 31.7% (4,579) [27]. This represents an extraordinary ascent for cryo-EM, which contributed a negligible number of structures annually until around 2015. The rate of growth is particularly significant in specific biological domains. For example, in the first seven months of 2021 alone, 78% of the 99 GPCR structures deposited in the PDB were determined by cryo-EM [28]. This trajectory underscores a fundamental shift in how structural biologists approach challenging targets, particularly large complexes and membrane proteins that have historically resisted crystallization.

Table 1: Annual PDB Structure Deposition by Method (2023 Data)

| Method | Number of Structures | Percentage of Annual Deposits |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | 9,601 | 66% |

| Cryo-EM | 4,579 | 31.7% |

| NMR | 272 | 1.9% |

| Other/Multiple Methods | Remaining | <0.4% |

Market Growth and Financial Indicators

The trends in PDB depositions are mirrored by financial projections in the structural biology market, indicating strong and sustained investment in both techniques. The global 3D protein structures analysis market was valued at $2.80 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach $6.88 billion by 2034, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.40% [29]. Within this expanding market, X-ray crystallography currently holds the largest technology share at 35% [29], reflecting its established infrastructure and continued relevance.

Concurrently, the market for cryo-EM structure analysis services is projected to grow from an estimated $1.30 billion in 2025 to $2.51 billion by 2032, exhibiting a CAGR of 9.8% [30]. This robust growth is fueled by rising adoption in pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, which represent the largest end-user segment (23.5%) of the cryo-EM services market [30]. These financial indicators confirm that the scientific trends observed in the PDB are supported by substantial and growing capital investment, particularly in cryo-EM infrastructure and services.

Table 2: Market Size and Growth Projections for Structural Analysis Techniques

| Metric | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Share (2024) | 35% of 3D Protein Analysis Market [29] | Segment of larger market |

| Service Market Value | Part of broader crystallography market | $1.30B (2025) → $2.51B (2032) [30] |

| Projected CAGR | Part of overall market growth | 9.8% (2025-2032) [30] |

| Dominant End User | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies [29] | Pharmaceutical Companies (23.5% share) [30] |

Technical Comparison: Cryo-EM vs. X-ray Crystallography

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

The technical principles underlying X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM are fundamentally different, which explains their distinct applications and recent market trajectories.

X-ray crystallography relies on Bragg's Law of X-ray diffraction by crystals. The process involves growing a highly ordered, three-dimensional crystal of the purified macromolecule. When exposed to a beam of X-rays, the crystal diffracts the X-rays, producing a pattern of spots on a detector [31] [27]. The intensities of these spots are measured, and the critical "phase problem" is solved through methods like molecular replacement or experimental phasing (e.g., SAD/MAD). This allows for the calculation of an electron density map into which an atomic model is built and refined [18].

Cryo-EM, specifically single-particle analysis, uses a high-energy electron beam to image individual macromolecules flash-frozen in a thin layer of vitreous ice. The magnetic objective lens of the microscope produces both a diffraction pattern and a magnified image [31]. Hundreds of thousands of 2D particle images are collected, then computationally classified, aligned, and averaged to reconstruct a 3D density map [31] [32]. This process bypasses the need for crystallization and directly visualizes particles in a near-native state.

Comparative Technical and Operational Metrics

The choice between cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography is often dictated by the sample properties, project requirements, and available resources.

Table 3: Technical and Operational Comparison for Method Selection

| Aspect | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Molecular Size | >100 kDa [32] | <100 kDa [32] |

| Sample Amount Required | 0.1-0.2 mg [32] | Typically >2 mg [32] |

| Sample Purity & Homogeneity | Tolerates moderate heterogeneity [32] | Requires high homogeneity [32] |

| Typical Resolution Range | 2.5-4.0 Å [32] | Can achieve sub-1.0 Å [32] |

| Ideal For | Membrane proteins, large complexes, dynamic systems [32] | Soluble proteins, small molecules, high-throughput ligand screening [18] [32] |

| Key Technical Bottleneck | Ice quality, particle alignment, computational processing [32] | Crystal growth and optimization [18] |

| Equipment Access | High-end electron microscope [32] | Synchrotron radiation source [18] [32] |

Complementary Applications in Researching Complex Structures

Synergistic Use in Structural Studies

Rather than being mutually exclusive, cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography are increasingly used in complementary ways to provide a more complete understanding of complex biological structures. This synergy is powerfully demonstrated in two major approaches:

Docking crystallographic structures into cryo-EM maps: A widely adopted practice involves determining the low-resolution architecture of a large complex by cryo-EM and then docking high-resolution atomic models of its components (solved by X-ray crystallography) into the EM density. This allows for the interpretation of the entire assembly's structure and interactions. Software packages like Situs, EMfit, and UCSF Chimera are used for rigid-body docking, while flexible docking tools like Flex-EM and MDFF can account for conformational differences [31]. This approach was critical in elucidating the architecture of the yeast RNA exosome complex [31].

Using cryo-EM maps to solve the phase problem in crystallography: For a macromolecule that can be crystallized, a medium-resolution cryo-EM reconstruction can serve as an initial molecular model to obtain phase information for the high-resolution crystallographic data. This can streamline the structure determination process for challenging crystals [31].

Application-Specific Strengths

Each technique holds distinct advantages for specific research scenarios, which underpins their continued coexistence and collaborative use.

Cryo-EM excels in:

- Membrane Protein Analysis: It allows the study of membrane proteins embedded in lipid nanodiscs, preserving a near-native lipid environment that is often disrupted by the detergents needed for crystallization [28] [32].

- Visualizing Dynamic Structures: Cryo-EM can capture multiple conformational states of a macromolecule from a single sample preparation. Advanced computational classification can deconvolute this structural heterogeneity, providing insights into functional mechanisms and energy landscapes [32] [26].

- Analyzing Large and Fragile Complexes: Very large macromolecular assemblies (>1 MDa) that are difficult or impossible to crystallize, such as ribosomes or viral capsids, are ideal targets for cryo-EM [31] [32].

X-ray Crystallography remains superior for:

- Ultra-High-Resolution Studies: It routinely achieves resolutions higher than cryo-EM (often 1.5-2.5 Å), enabling precise visualization of atoms, water molecules, and ions within a structure [32].

- High-Throughput Ligand Screening: The well-established pipeline of soaking small molecules or fragments into crystals makes crystallography exceptionally powerful for rapid, iterative structure-based drug design and optimization [28] [18].

- Time-Resolved Studies: Using techniques like serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) with X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), crystallography can capture molecular movies of biochemical reactions at atomic resolution, providing dynamic information as a function of time [27] [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful structure determination, regardless of the method, relies on high-quality samples and specialized reagents. The following table details key materials essential for workflows in both cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Biology

| Reagent / Material | Function | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Reagents & Screens | Precipitants, buffers, and salts to induce and optimize crystal growth by slowly driving the protein out of solution. | X-ray Crystallography [33] |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) that prevent the formation of crystalline ice during vitrification, preserving the sample structure. | Both (for crystal cryo-cooling & vitreous ice) [27] |

| Grids (e.g., Gold or Copper) | Microscope meshes that support the thin layer of vitreous ice containing the sample for imaging in the electron microscope. | Cryo-EM |

| Detergents & Lipids | For solubilizing and stabilizing membrane proteins in mimetic environments like micelles, nanodiscs, or the lipidic cubic phase (LCP). | Both (esp. Membrane Proteins) [18] |

| Selenomethionine | An amino acid used in recombinant protein expression to incorporate selenium atoms for experimental phasing via SAD/MAD. | X-ray Crystallography [18] |

| Negative Stains (e.g., Uranyl Acetate) | Heavy metal salts that embed and contrast biological samples for rapid initial screening of sample quality by EM. | Cryo-EM (initial screening) [26] |

The analysis of deposition trends in the Protein Data Bank confirms a definitive and rapid growth in the share of structures solved by cryo-EM, a trend driven by its ability to tackle biological targets that have long eluded crystallographic approaches. This shift, however, does not spell the obsolescence of X-ray crystallography. Instead, the landscape of structural biology is evolving into a more diversified and powerful field.

X-ray crystallography maintains its critical role in delivering ultra-high-resolution snapshots and enabling high-throughput drug discovery pipelines for a vast range of soluble targets. Meanwhile, cryo-EM has opened new frontiers by enabling the study of large, dynamic, and membrane-embedded complexes in near-native states. The future of structural research on complex systems lies not in choosing one technique over the other, but in strategically leveraging their complementary strengths. The synergistic combination of both methods—using cryo-EM for overall architecture and conformational landscapes and X-ray crystallography for atomic-level detail of components and ligand interactions—provides a comprehensive pipeline for deciphering the molecular mechanisms of life and accelerating the development of new therapeutics.

Strategic Application: Choosing the Right Technique for Your Target

For decades, X-ray crystallography has stood as the dominant technique for determining the three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules at atomic resolution, accounting for approximately 84% of structures in the Protein Data Bank [18]. This article provides a comprehensive examination of the complete X-ray crystallography workflow, from the initial challenge of crystallization to the final stages of model refinement and validation. Framed within a broader comparison with cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), we explore the technical requirements, advantages, and limitations of crystallography for complex structure research. Understanding this detailed workflow is fundamental for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to select the most appropriate structural biology technique for their specific projects, particularly as cryo-EM emerges as a complementary powerhouse for studying challenging macromolecular assemblies [31] [34].

The X-ray Crystallography Workflow: A Step-by-Step Technical Analysis

Sample Preparation and Crystallization

The journey to an atomic-resolution structure begins with the most unpredictable and often most challenging step: obtaining high-quality crystals. This process requires a pure, homogeneous, and stable protein sample. Typically, a starting point of at least 5 mg of protein at a concentration of around 10 mg/mL is necessary to screen a wide range of crystallization conditions [35] [18]. The fundamental principle of crystallization is to slowly bring the protein out of solution in a controlled manner that promotes the formation of an ordered, three-dimensional lattice rather than amorphous precipitation [35].

Crystallization is typically achieved through vapor diffusion methods, most commonly using the hanging-drop or sitting-drop techniques. In these setups, a small drop containing a mixture of protein solution and precipitant is placed in a sealed chamber against a larger reservoir of precipitant solution. The water vapor pressure difference causes the droplet to equilibrate with the reservoir, slowly increasing the concentration of both the protein and the precipitant until supersaturation is achieved, leading to nucleation and crystal growth [35]. This process can take anywhere from days to weeks and requires optimization of numerous variables including precipitant type and concentration, buffer, pH, temperature, and additives [18]. For particularly challenging targets like membrane proteins, specialized methods such as lipidic cubic phase (LCP) crystallization have been developed to provide a more native lipid environment, proving highly successful for GPCR structural biology [18].

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials in Crystallization

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|

| Precipitant Solutions (e.g., PEGs, salts, organic solvents) | Induces protein supersaturation by excluding water or competing for hydration. |

| Crystallization Plates (e.g., 24-well sitting/hanging drop) | Provides a platform for vapor diffusion experiments. |

| Buffer Additives & Ligands | Modifies protein surface or stabilizes a specific conformational state to promote crystal packing. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) | Prevents ice crystal formation during flash-cooling for cryo-data collection. |

| Detergents (for membrane proteins) | Mimics the native lipid environment and solubilizes membrane proteins. |

Data Collection and Initial Processing

Once a diffraction-quality crystal is obtained, it is mounted on a goniometer and exposed to an intense, monochromatic beam of X-rays. The crystal is rotated through a series of angles, and at each orientation, the diffracted X-rays produce a pattern of spots, known as reflections, on the detector [36] [35]. The quality of this data is paramount, as it forms the foundation for the entire structure determination process.

The majority of high-resolution data collection is performed at third-generation synchrotrons, which provide extremely bright, tunable X-ray beams that allow for the study of smaller crystals and faster data acquisition [18]. The modern standard is "shutterless" data collection with fine φ-slicing, where the crystal is rotated continuously while the detector reads out images at a high frequency. This method eliminates synchronization errors between the mechanical shutter and goniometer rotation, reduces background, and improves the accuracy of intensity measurements [36].

The initial processing of the hundreds to thousands of diffraction images is handled by specialized software packages such as Mosflm, HKL-2000, or XDS [36]. The first computational step is indexing, where the dimensions and orientation of the crystal's unit cell are determined, and each reflection is assigned Miller indices (h, k, l) that describe its position in reciprocal space [35]. This is followed by integration, where the intensity of each reflection is precisely measured across the series of images. Finally, the data from all images are merged and scaled to create a consistent dataset. The quality of the data is often reported using the R-factor, which measures the agreement between multiple measurements of symmetry-equivalent reflections [36] [35].

The Phase Problem and Initial Model Building

A critical and unique challenge in X-ray crystallography is the phase problem. While the diffraction pattern captured by the detector provides the amplitudes of the structure factors, the phase information—essential for calculating the electron density map—is lost during data collection [35] [18]. Overcoming this problem is a pivotal step in the workflow, typically addressed by one of two primary methods:

- Molecular Replacement (MR): This is the most common method when a structurally similar model is already available. The known model is computationally placed and oriented within the unit cell of the target crystal, providing initial phase estimates [18].

- Experimental Phasing: For novel structures with no homologous model, phase information must be obtained experimentally. This involves introducing heavy atoms (e.g., selenium via selenomethionine, or other metals) into the crystal. Techniques like Single/Multiple Isomorphous Replacement (SIR/MIR) or Single/Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD/MAD) exploit the anomalous scattering from these atoms to solve the phase problem [31] [18].

Once initial phases are obtained, they are combined with the measured amplitudes to compute an electron density map. Researchers then begin the process of model building, fitting the amino acid or nucleotide sequence of the macromolecule into the electron density. This initial model is typically rough and requires significant refinement [35].

Model Refinement and Validation

Refinement is an iterative cycle of computational adjustment that improves the agreement between the atomic model and the observed diffraction data, while ensuring the model conforms to standard stereochemical constraints [35]. The atomic coordinates, atomic displacement parameters (B-factors), and occupancy are adjusted to minimize the difference between the calculated structure factors (Fc) from the model and the observed structure factors (Fo) from the experiment. The progress is tracked by a reduction in the R-work and R-free factors. R-free is calculated using a small subset of reflections not used in refinement and serves as a crucial unbiased validation metric to prevent overfitting [35].

Throughout the refinement process, the model is continuously validated. This includes checking for proper bond lengths and angles, Ramachandran plot outliers, and clashes between atoms. Techniques like omit maps—where part of the model is omitted before recalculating the electron density—are used to validate specific features and avoid model bias [35]. The final, refined atomic model is then deposited in a public database such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB), making it available to the global scientific community [35].

Performance Comparison: X-ray Crystallography vs. Cryo-EM

When selecting a technique for a structural biology project, researchers must consider the inherent strengths and limitations of each method. The following tables provide a direct comparison of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM across several critical parameters.

Table 2: Sample and Methodological Requirements

| Aspect | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Amount | >2 mg typically [34] | 0.1-0.2 mg [34] |

| Molecular Size | Optimal <100 kDa [34] | Optimal >100 kDa [34] |

| Sample Purity & Homogeneity | High homogeneity required [34] | Moderate heterogeneity acceptable [34] |

| Key Challenge | Obtaining well-ordered, diffraction-quality crystals [18] | Avoiding air-water interface, achieving thin ice [37] |

| Sample State | Molecules in crystal lattice packing constraints [31] | Molecules in near-native, vitrified solution state [31] [34] |

Table 3: Technical and Operational Considerations

| Factor | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | 1.5-2.5 Å (up to 1.0 Å possible) [34] | 2.5-4.0 Å (2-3 Å maximum) [34] |

| Data Collection Time | Minutes to hours per dataset [34] | Hours to days per dataset [34] |

| Data Processing | Established pipelines, standard workstation often sufficient [34] [36] | Intensive computing needed, high-performance clusters or cloud computing (e.g., AWS) [34] [38] |

| Key Bottleneck | Crystal growth and optimization (weeks to months) [34] | Sample preparation (grid freezing) and data processing [34] [37] |

Table 4: Application Strengths and Limitations

| Application | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Proteins | Possible with detergents/LCP, but often challenging [18] | Ideal; preserves native lipid environment [34] [37] |

| Large Complexes | Difficulties with crystal quality for very large/complex targets [18] | Excellent; no size limitations [34] |

| Dynamic Structures | Captures stable, low-energy conformations [34] | Captures multiple conformational states in a single sample [34] |

| Ligand/Small Molecule Studies | Ultra-high resolution for precise binding site analysis; established for fragment screening [34] [18] | Visualization of drug binding sites; growing use for challenging targets [34] |

Integrated Workflows and Emerging Synergies

Rather than being purely competitive, X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM are powerfully complementary. A common integrated approach involves docking high-resolution X-ray structures of individual subunits or domains into lower-resolution cryo-EM maps of larger complexes, a practice known as rigid-body docking [31]. This hybrid method was instrumental in elucidating the architecture of the yeast RNA exosome complex, where crystallographic models of subcomplexes were docked into a ~18 Å resolution EM map to reveal RNA processing mechanisms [31]. Furthermore, cryo-EM maps can sometimes serve as initial models to solve the phase problem in X-ray crystallography [31].

Emerging computational tools are also bridging the gap between these techniques. For instance, deep learning models like Metric Ion Classification (MIC) are now being applied to classify ions and water molecules in both cryo-EM maps and crystal structures, improving the accuracy of the final refined model regardless of the experimental method [10]. As cryo-EM continues to advance in resolution and automation, and X-ray crystallography refines its throughput and capabilities for smaller crystals, the synergistic combination of both methods will undoubtedly provide the most comprehensive structural insights into complex biological machineries.

The detailed workflow of X-ray crystallography—from the art of crystallization to the computational rigor of phase determination and refinement—establishes it as a powerful method for achieving atomic-resolution structures. Its unparalleled precision for well-behaved targets that can be crystallized makes it indispensable for detailed mechanistic studies and structure-based drug design. However, the comparison with cryo-EM reveals a clear trade-off: while crystallography offers higher ultimate resolution, cryo-EM provides unparalleled flexibility for studying large, heterogeneous, and membrane-embedded complexes in near-native states. For researchers in complex structure research, the choice is not a matter of which technique is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for their specific biological question, sample characteristics, and project resources. The future of structural biology lies in leveraging the complementary strengths of both these formidable techniques.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a powerful technique in structural biology, capable of determining high-resolution structures of biologically significant complexes that are difficult to crystallize. This guide provides a detailed comparison of cryo-EM workflows against traditional X-ray crystallography, with a focus on the technical progression from sample vitrification to three-dimensional reconstruction. We examine automated vitrification systems, data collection strategies, and computational processing pipelines that have contributed to the "resolution revolution" in structural biology. Experimental data and protocol details are presented to objectively compare the performance, requirements, and outputs of these complementary structural determination methods.

Structural biology employs multiple techniques to visualize biological macromolecules, with X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM serving as the two primary methods for high-resolution structure determination. While X-ray crystallography has historically dominated the field, solving most atomic-resolution structures, cryo-EM has recently undergone a technical revolution that now enables it to achieve comparable resolutions for many biologically significant targets [31]. The fundamental distinction between these techniques lies in their sample requirements: X-ray crystallography depends on highly ordered three-dimensional crystals, whereas cryo-EM analyzes individual particles in vitreous ice [31] [39]. This difference makes cryo-EM particularly valuable for studying large complexes, membrane proteins, and heterogeneous samples that prove challenging to crystallize.

The synergy between these techniques is increasingly important in structural biology. Cryo-EM can provide low-resolution maps into which high-resolution X-ray structures of domains or homologs can be docked, while cryo-EM reconstructions can serve as initial models for solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography [31]. Understanding the complete workflow from sample preparation to final reconstruction is essential for researchers to effectively leverage cryo-EM's capabilities and integrate them with crystallographic approaches.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography

| Parameter | Cryo-EM | X-Ray Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Sample State | Vitrified solution in native state [39] | Solid crystal in constrained packing [31] |

| Resolution Range | ~3 Å to ~3 nm [31] | Atomic resolution (typically higher for small molecules) [39] |

| Ideal Sample Types | Membrane proteins, large complexes, ribosomes, virions [39] | Crystallizable samples, soluble proteins [39] |

| Molecular Weight | >100 kDa preferred, though smaller structures now possible [39] | Broad molecular weight ranges [39] |

| Sample Amount Required | Nanograms to micrograms [39] | Micrograms to milligrams [39] |

| Primary Limitations | Particle size limitations, computational complexity [40] | Difficult crystallization, static crystalline state [39] |

| Structural Information | Captures structural heterogeneity [31] | Single conformational state [31] |

The Cryo-EM Workflow: From Sample to Structure

Sample Preparation and Vitrification

The initial and most critical step in cryo-EM is sample preparation, which aims to preserve biological structures in a native, hydrated state by rapid freezing. In vitrification, samples are rapidly frozen in liquid ethane or an ethane/propane mixture, preventing ice crystal formation and embedding specimens in vitreous (amorphous) ice [41] [39]. This process requires freezing rates exceeding 100,000°C/s to maintain the water in a glass-like state [41]. Traditional blotting-based methods often lead to inconsistent ice thickness and sample loss, with less than 0.1% of the original sample remaining on the grid [41].

Advanced Vitrification Protocol: Suction-Based Approach

Recent technological developments have introduced automated vitrification devices that replace blotting paper with suction-based excess liquid removal. The Linkam plunger exemplifies this approach with the following workflow [41]:

- Grid Handling: Automated retrieval of EM grids from storage boxes

- Surface Treatment: In-situ glow-discharging to render support films hydrophilic

- Sample Application: Grid immersion in protein suspension

- Thin Film Formation: Slow grid retrieval from solution with simultaneous suction via tubes

- Optical Inspection: Real-time monitoring of thin film formation using transmission/reflection light microscopy

- Dew-Point Control: Precise environmental control to stabilize thin films

- Plunge-Freezing: Vitrification in liquid ethane at -183°C

This methodology enables visual assessment of thin film quality before vitrification, addressing a significant bottleneck in conventional cryo-EM workflows [41]. The system's environmental chamber maintains temperatures between 3-50°C with controlled humidity, while the cryogenic chamber maintains liquid ethane at a constant temperature and level [41].

Alternative Preparation: High-Pressure Freezing and Freeze Substitution

For thicker samples such as cells and tissues, high-pressure freezing followed by freeze substitution provides an alternative pathway. This technique involves [42]:

- High-Pressure Freezing: Instant physical immobilization of cell constituents under high pressure

- Freeze Substitution: Replacement of "frozen" water with organic solvent containing chemical fixatives at low temperatures

- Gradual Warming: Temperature increases (typically 2°C per hour) from -90°C to 0°C

- Resin Embedding: Infiltration with resins like Spurr's or LR-White for sectioning

This approach preserves cellular ultrastructure with minimal artifacts and enables examination of 200-300 nm sections by electron tomography [42].

Table 2: Cryo-EM Sample Preparation Methods and Applications

| Method | Principle | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blotting-Based Plunge Freezing | Filter paper removes excess liquid [41] | Purified proteins, viruses [41] | Widely available, established protocols | Inconsistent thickness, sample loss [41] |

| Suction-Based Plunge Freezing | Tubes remove excess liquid [41] | Proteins, liposomes, bacteria, cells [41] | Reproducible thickness, minimal sample loss | Specialized equipment required [41] |

| High-Pressure Freezing | High pressure prevents ice crystallization [42] | Cells, tissues, organelles [42] | Superior structural preservation | Sample size restrictions [42] |

| Negative Staining | Heavy metal salt contrast [40] | Rapid sample screening [40] | High contrast, fast preparation | Resolution limited to ~20Å [40] |

Cryo-EM Workflow Diagram

Data Acquisition and Imaging

Modern cryo-EM data collection leverages highly automated systems that integrate microscope and detector control for continuous, unsupervised operation [43]. Current direct electron detectors (DDs) can collect movies comprising 30-100 frames per imaging area, with field-of-view sizes up to 8k×8k pixels [43]. These systems typically generate 1,500-2,000 movies per 24-hour period, representing approximately 3 terabytes of raw data daily [43].

Single Particle Analysis (SPA) Acquisition:

- Automated Systems: Leginon, EPU, and SerialEM enable multigrid support and continuous data collection [43] [44]

- Real-Time Monitoring: Smart EPU Software with embedded CryoSPARC Live provides AI-driven automation and real-time image quality feedback [44]

- Throughput: Typical collection of 1,000-2,000 movies per 24-hour session [43]

Cryo-Electron Tomography (Cryo-ET) Acquisition:

- Tilt Series Collection: Automated acquisition of 20-100 tilts per series, with 4-10 movie frames per tilt [43]

- Correlative Microscopy: Maps Software integrates light and electron microscopy data for precise targeting [44]

- Sample Thinning: Cryo-focused ion beam (cryo-FIB) milling for thick cellular samples [39]

Image Processing and 3D Reconstruction

The computational pipeline for cryo-EM has evolved to handle massive datasets requiring specialized hardware and software solutions. Key developments include GPU acceleration, cloud computing integration, and deep learning applications [43].

Single Particle Analysis Processing Protocol:

Movie Processing:

Particle Selection:

- Automated particle picking using Gautomatch or similar tools [43]

- Extraction of particle stacks (typically 256×256 pixels)

2D Analysis and 3D Reconstruction:

Model Building:

- Atomic model building into cryo-EM density maps

- Validation against known physical constraints

Tomography Processing Protocol:

Tilt Series Alignment:

- Fiducial-based or patch tracking alignment

- Reconstruction using weighted back-projection or SIRT methods

Subtomogram Averaging:

- Particle identification in 3D (manually or using convolutional neural networks) [43]

- Extraction and alignment of subvolumes

- Averaging to enhance signal-to-noise ratio

Segmentation and Analysis:

- Manual or deep learning-based segmentation using Amira, IMOD, or SuRVoS [43]

- Visualization and interpretation of cellular landscapes

Table 3: Computational Requirements for Cryo-EM Processing

| Processing Stage | Hardware Requirements | Software Tools | Output Data Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frame Alignment | GPU acceleration (MotionCor2) [43] | MotionCor2, Relion [43] | ~50 GB/day (from 3 TB raw) [43] |

| Particle Picking | GPU acceleration [43] | Gautomatch, Relion [43] | ~50 GB for 200k particles [43] |

| 2D Classification | Multi-core CPU/GPU [43] | CryoSPARC, Relion [43] | Minimal (class averages) |

| 3D Reconstruction | High-memory GPU clusters [43] | Relion, CryoSPARC, Frealign [43] | ~50 GB per 3D model [43] |

| Tomography | Large-memory workstations [43] | IMOD, Dynamo, PEET [43] | ~1 GB per tomogram [43] |

Integrated Structural Biology: Combining Cryo-EM and X-Ray Crystallography

The most powerful structural biology approaches often combine multiple techniques to overcome their individual limitations. Two primary integration strategies have emerged [31]:

Docking of X-ray structures into cryo-EM maps: High-resolution crystal structures of domains or homologs can be docked into lower-resolution cryo-EM maps of entire complexes using rigid-body (Situs, EMfit, UCSF Chimera) or flexible docking (Flex-EM, MDFF, iMODFIT) algorithms [31].

Cryo-EM as a phasing source for crystallography: Cryo-EM reconstructions can provide initial models for solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography, particularly for difficult-to-phase crystals [31].

Recent developments in time-resolved studies aim to capture biological molecules in motion rather than as static structures. The combination of cryo-EM with X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) and synchrotron facilities promises to visualize structural changes with high temporal and spatial resolution [45]. These integrated approaches are particularly valuable for understanding functional mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutics [45].

Research Reagent Solutions for Cryo-EM Workflows

Table 4: Essential materials and reagents for cryo-EM experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| EM Grids | Sample support for imaging [40] | Copper, gold, nickel; 200-400 mesh [40] |

| Support Films | Create thin sample layer [40] | Continuous carbon (negative stain), holey carbon (cryo) [40] |

| Glow Discharger | Render support hydrophilic [40] | Surface treatment for even sample spreading [40] |

| Cryogen | Vitrification medium [41] | Liquid ethane or ethane/propane mixture [41] |

| Negative Stains | Contrast enhancement [40] | Uranyl acetate, uranyl formate, ammonium molybdate [40] |

| Freeze Substitution Cocktail | Dehydration and fixation [42] | Acetone with OsO₄, glutaraldehyde, uranyl acetate [42] |

| Embedding Resins | Sample support for sectioning [42] | Spurr's, Epon/Araldite, LR-White, HM20 [42] |

| Alignment Gold Fiducials | Tomography reference markers [40] | Colloidal gold particles for tilt series alignment [40] |

The cryo-EM workflow represents a comprehensive pipeline from sample vitrification to high-resolution reconstruction that complements traditional X-ray crystallography approaches. Automated vitrification systems with suction-based thin film formation address previous limitations in sample preparation reproducibility [41]. Meanwhile, advances in direct electron detectors and computational processing have dramatically increased both the resolution and throughput of cryo-EM structures [43]. The integration of cryo-EM with X-ray methods provides a powerful synergistic approach for structural biology, particularly for complex targets that resist crystallization [31] [45]. As both techniques continue to evolve, their combined application promises to deliver unprecedented insights into molecular mechanisms and accelerate drug discovery efforts.

For researchers in structural biology and drug development, selecting the appropriate technique for determining a macromolecular structure is a critical decision. This choice is often dictated by the sample itself—its properties, availability, and stability. For decades, X-ray crystallography was the dominant workhorse, but a technological revolution has established cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) as a powerful complementary technique [18] [46]. Within the context of complex structure research, understanding the precise sample requirements for each method is essential for project planning and success. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of the sample prerequisites for X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, supporting the broader thesis that the optimal technique is often dictated by the sample's characteristics and the research question at hand.

Core Sample Requirements at a Glance

The following table summarizes the key sample-related requirements for X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, highlighting the fundamental differences that influence method selection.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Sample Requirements for X-ray Crystallography and Cryo-EM

| Requirement | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|