X-ray Crystallography vs. Cryo-EM: A Structural Biologist's Guide to Choosing the Right Tool

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for researchers and drug development professionals.

X-ray Crystallography vs. Cryo-EM: A Structural Biologist's Guide to Choosing the Right Tool

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles, current methodology, practical troubleshooting, and a direct validation of both techniques. Drawing on the latest data and trends, including the rising contribution of cryo-EM to the PDB, it offers a clear framework for selecting the optimal method based on project goals, sample characteristics, and resource constraints. The scope extends to advanced applications like time-resolved studies and the analysis of membrane proteins and small molecules, concluding with a forward-looking synthesis on the convergent future of structural biology techniques.

The Evolving Landscape of Structural Biology: From X-ray Dominance to the Cryo-EM Revolution

Structural biology relies on powerful techniques to determine the three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules, with X-ray crystallography and single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) serving as two pivotal methods. For decades, X-ray crystallography has been the dominant technique for solving atomic-resolution structures, relying on the fundamental principle of Bragg's Law to interpret diffraction patterns from crystalline samples [1] [2]. In contrast, single-particle cryo-EM has emerged more recently as a revolutionary technique that can determine high-resolution structures from non-crystalline, frozen-hydrated samples by computationally analyzing thousands of individual particle images [1] [3].

These two methods are not mutually exclusive but rather highly complementary approaches that together provide a more comprehensive understanding of biological structures and mechanisms [1] [4]. This guide provides a detailed objective comparison of their core principles, methodologies, and applications, specifically framed within the context of structural biology research and drug development. We will examine the theoretical foundations, experimental workflows, technical requirements, and output characteristics of both techniques, enabling researchers to select the most appropriate method for their specific structural biology challenges.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Bragg's Law in X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography is founded on Bragg's Law, a fundamental principle that describes the condition for constructive interference of X-rays diffracted by crystalline materials. Formulated in 1912 by Sir William Lawrence Bragg and his father Sir William Henry Bragg, this law establishes the relationship between the X-ray wavelength, the distance between atomic planes in the crystal, and the angle of diffraction [5] [6].

The Bragg's Law equation is expressed as: nλ = 2d sinθ, where:

- n is an integer representing the order of the reflection

- λ is the wavelength of the incident X-ray beam

- d is the spacing between consecutive atomic planes in the crystal

- θ is the angle between the incident ray and the scattering planes [5] [7] [6]

In practical terms, Bragg's Law governs the specific angles at which a crystal will produce strong diffraction peaks due to constructive interference when illuminated with X-rays [5]. These "Bragg reflections" occur when X-rays scattering from different crystal planes remain in phase, producing intense spots in the diffraction pattern that can be measured and used to compute the electron density and ultimately determine the atomic structure of the crystallized molecule [7] [6]. The resolution limit in crystallography is directly related to the smallest d-spacing that can be measured, which depends on the maximum diffraction angle (θ) achievable [7].

Single-Particle Analysis in Cryo-EM

Single-particle analysis in cryo-EM operates on fundamentally different principles than X-ray crystallography. Instead of relying on diffraction from crystalline samples, it directly images individual macromolecules using a transmission electron microscope and computationally reconstructs their three-dimensional structure [1] [3].

The core principle involves collecting two-dimensional projection images of thousands to millions of identical, randomly oriented macromolecules preserved in a thin layer of vitreous ice [1] [3]. Through sophisticated image processing algorithms, these particles are identified, aligned, classified, and averaged to generate a three-dimensional electron density map [1]. The reconstruction process relies on the mathematical principles of tomography and the ability to computationally determine the relative orientation of each particle based on common lines in Fourier space [1].

The resolution of the final reconstruction depends on multiple factors including the number of particle images collected, the homogeneity of the sample, the accuracy of particle alignment, the performance of the electron microscope (particularly detector technology and beam coherence), and the effectiveness of computational corrections for microscope aberrations and beam-induced particle movement [1] [8]. Unlike crystallography, where resolution is determined by the highest angle diffraction data, cryo-EM resolution is typically estimated using statistical measures such as the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) between independently processed half-maps [8].

Methodological Comparison

Experimental Workflows

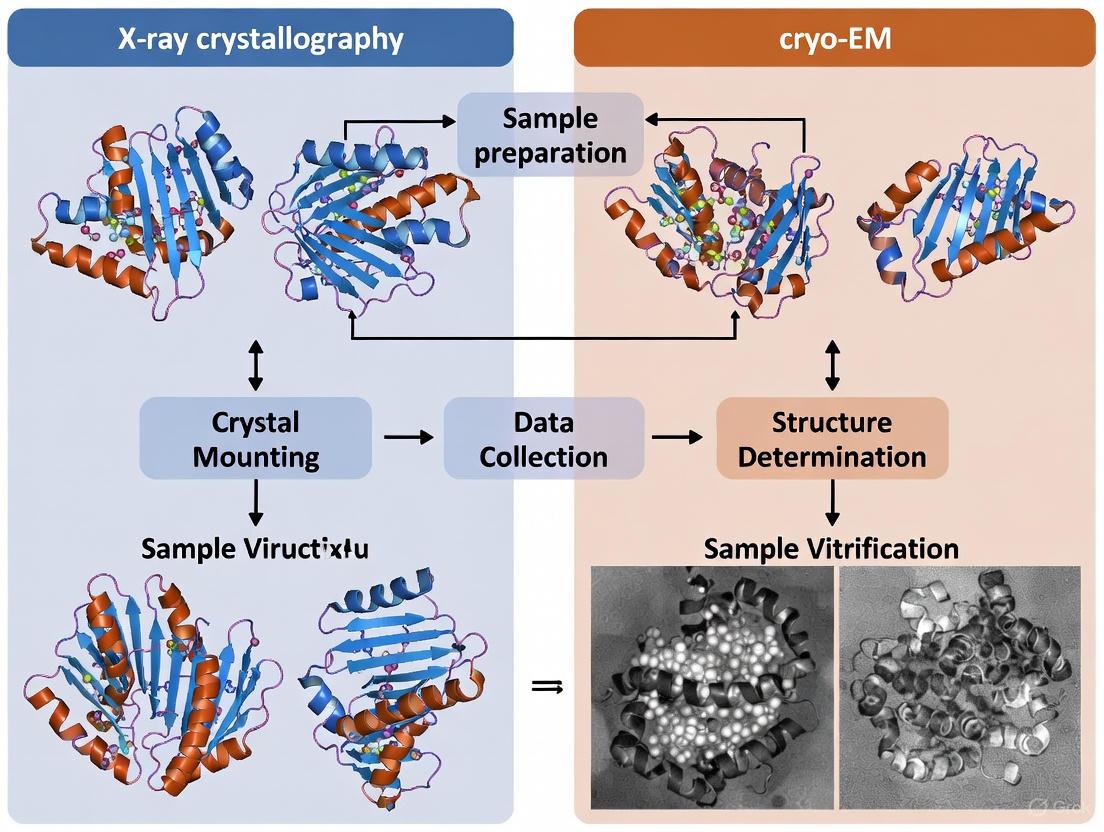

The experimental workflows for X-ray crystallography and single-particle cryo-EM differ significantly in their sample preparation, data collection, and data processing stages, each with distinct advantages and challenges.

X-ray Crystallography Workflow:

- Protein Purification: Obtaining highly pure, homogeneous protein samples in sufficient quantities (typically milligrams) [1]

- Crystallization: Screening hundreds to thousands of conditions to obtain well-ordered, diffraction-quality crystals through vapor diffusion, microbatch, or other methods [2]

- Cryo-cooling: Flash-freezing crystals in liquid nitrogen to minimize radiation damage during data collection [2]

- Data Collection: Mounting crystals in the X-ray beam (often at synchrotron sources) and collecting diffraction patterns at various orientations [2]

- Data Processing: Indexing and integrating diffraction spots, merging data from multiple crystals, and determining phases through molecular replacement, anomalous scattering, or other methods [2]

- Model Building and Refinement: Interpreting the electron density map to build an atomic model and iteratively refining it against the diffraction data [2]

Single-Particle Cryo-EM Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Purifying the macromolecular complex and applying it to specialized grids [3]

- Vitrification: Rapidly plunging the grid into liquid ethane/propane to form a thin layer of vitreous ice that preserves molecules in near-native state [3]

- Screening: Identifying promising samples with optimal particle distribution and ice thickness [3]

- Data Collection: Automatically acquiring thousands to millions of particle images using high-end cryo-electron microscopes [1] [3]

- Image Processing: Computational steps including particle picking, 2D classification, 3D initial model generation, heterogeneous classification, and high-resolution refinement [1]

- Model Building and Refinement: Interpreting the cryo-EM density map to build and refine an atomic model [1]

Technical Requirements and Data Output

The technical requirements, sample characteristics, and data output differ substantially between the two techniques, making each suitable for different types of structural biology problems.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of X-ray Crystallography and Single-Particle Cryo-EM

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Single-Particle Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Requirement | Highly ordered 3D crystals | Purified macromolecules in solution |

| Sample Amount | 0.1-1 mg (typically larger quantities needed for screening) | <0.1 mg (significantly less material required) [1] |

| Sample State | Molecules constrained in crystal lattice | Near-native state in vitreous ice [1] [4] |

| Molecular Weight Range | No inherent upper limit (small molecules to large complexes) | Typically >50 kDa for high resolution, smaller molecules possible with advanced methods [4] |

| Structural Heterogeneity | Challenging for flexible or dynamic systems | Can resolve multiple conformational states through classification [1] [4] |

| Typical Resolution Range | 1.0-3.5 Å (atomic to near-atomic) | 1.5-4.0 Å for well-behaved samples (near-atomic to sub-nanometer) [1] [8] |

| Membrane Protein Success | Challenging but possible with detergent screening and lipidic cubic phase | Particularly well-suited with many recent successes [4] |

| Data Collection Time | Minutes to hours per dataset | Days to weeks for high-resolution data [3] |

| Key Limiting Factor | Crystal quality and diffraction resolution | Particle homogeneity, microscope performance, computational resources [1] [8] |

Table 2: Statistical Comparison of Structure Determination Methods (Based on PDB Depositions)

| Method | Structures in PDB (2023) | Percentage of Total | Historical Dominance | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | ~9,601 | ~66% | ~86% of all structures | Declining proportion but still dominant [2] |

| Cryo-EM | ~4,579 | ~32% | Minimal until 2015 | Rapidly increasing (resolution revolution) [9] [2] |

| NMR | ~272 | ~2% | Consistently small contribution | Stable for small proteins and dynamics [2] |

Comparative Experimental Data

Resolution and Data Quality Metrics

The assessment of resolution and data quality follows different conventions in X-ray crystallography and single-particle cryo-EM, reflecting their different physical principles and data characteristics.

In X-ray crystallography, resolution is traditionally determined by where to truncate the diffraction data based on quality metrics. Key statistics include:

- Signal-to-noise ratio (I/σ(I)): Traditionally truncated when [8]<="" been="" below="" data="" falls="" has="" highest="" in="" include="" li="" questioned="" recommendations="" resolution="" shell,="" standard="" the="" this="" though="" to="" weaker="" with="" σ(i)>="">

- [8]<="" been="" below="" data="" falls="" has="" highest="" in="" include="" li="" questioned="" recommendations="" resolution="" shell,="" standard="" the="" this="" though="" to="" weaker="" with="" σ(i)>="">Rmerge: Measures agreement between multiple measurements of the same reflection, but is inherently flawed as it depends on multiplicity [8] [8]<="" been="" below="" data="" falls="" has="" highest="" in="" include="" li="" questioned="" recommendations="" resolution="" shell,="" standard="" the="" this="" though="" to="" weaker="" with="" σ(i)>="">

- Rmeas: Multiplicity-independent R-factor that provides a more realistic measure of precision [8]

- Rp.i.m.: Precision-indicating merging R-factor for merged reflections [8]

- CC1/2: Pearson's correlation coefficient between random halves of measurements, considered a more reliable quality indicator [8]

The resolution in crystallography represents the smallest lattice spacing (dmin) that can be measured according to Bragg's law, typically reported based on the highest resolution shell where data quality statistics meet certain thresholds [8] [7].

In single-particle cryo-EM, resolution is typically determined using the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC), which measures the normalized cross-correlation coefficient between two independently determined half-maps in successive resolution shells [8]. The most widely accepted threshold is FSC = 0.143, known as the "gold standard," though the appropriate threshold remains debated [8]. Unlike crystallography, cryo-EM maps often exhibit resolution anisotropy, where resolution varies with direction, and local resolution variations across different regions of the map [8].

Table 3: Resolution Metrics and Quality Indicators

| Quality Measure | X-ray Crystallography | Single-Particle Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Resolution Metric | Bragg limit (dmin) based on diffraction angles | Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) between half-maps |

| Standard Threshold | Variable (I/σ, R-factors, CC1/2) | FSC = 0.143 ("gold standard") [8] |

| Typical High Resolution | 0.48 Å (current record) [8] | ~1.2 Å (current record for single-particle) [8] |

| Atomic Resolution Definition | ~1.2 Å or better ("Sheldrick's criterion") [8] | Not strictly defined, but ~1.5-2.0 Å considered near-atomic |

| Key Quality Indicators | I/σ(I), Rmerge, Rmeas, Rp.i.m., CC1/2, completeness, multiplicity | FSC, Q-score, particle orientation distribution, local resolution variations |

| Anisotropy | Can occur in diffraction (anisotropic truncation) | Common in reconstruction (direction-dependent resolution) [8] |

Complementary Applications and Hybrid Approaches

Rather than competing techniques, X-ray crystallography and single-particle cryo-EM increasingly serve complementary roles in structural biology, with hybrid approaches leveraging the strengths of both methods [1] [4].

One powerful application is docking crystallographic structures into cryo-EM maps, where high-resolution atomic models of individual components or homologs are fitted into lower-resolution cryo-EM maps of larger complexes [1]. This approach has been successfully applied to systems such as:

- Ryanodine receptor: The crystal structure of the SPRY2 domain was docked into a 10 Å resolution cryo-EM map, with the docked model showing excellent agreement (2.1 Å RMSD) with later high-resolution cryo-EM structures [1]

- Yeast RNA exosome complex: Docking of crystallographic structures into cryo-EM maps revealed mechanisms of RNA substrate recruitment and processing [1]

- Viral capsids and cytoskeletal filaments: Early applications demonstrating the power of combining crystallographic and EM data [1]

Docking methods include both rigid-body docking (using programs like Situs, EMfit, UCSF Chimera) and flexible docking (using Flex-EM, MDFF, iMODFIT, Rosetta) that can accommodate conformational differences between crystal structures and their counterparts in cryo-EM maps [1].

Conversely, cryo-EM can assist crystallography by providing initial phase information through molecular replacement, helping to solve the notorious "phase problem" in crystallography [4]. Low-to-medium resolution cryo-EM maps can serve as starting models for phasing crystallographic data, particularly for large complexes that are difficult to solve by traditional crystallographic phasing methods [1] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful structure determination by either method requires specialized reagents and materials optimized for each technique's specific requirements.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screens | Commercial kits with predefined conditions to identify initial crystallization hits | X-ray Crystallography |

| Cryoprotectants | Compounds (glycerol, ethylene glycol) to prevent ice formation during crystal cryo-cooling | X-ray Crystallography |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Matrix for crystallizing membrane proteins and peptides | X-ray Crystallography |

| EM Grids | Specimen supports (gold or copper with continuous or holey carbon films) for sample application | Cryo-EM |

| Vitrification Systems | Instruments for plunge-freezing samples in ethane/propane for vitreous ice formation | Cryo-EM |

| Direct Electron Detectors | Advanced cameras with high sensitivity and fast readout for recording particle images | Cryo-EM |

| Image Processing Software | Programs (RELION, cryoSPARC, EMAN2) for particle picking, classification, and reconstruction | Cryo-EM |

| Crystallography Data Suites | Software (HKL-2000, XDS, CCP4, PHENIX) for data processing, phasing, and refinement | X-ray Crystallography |

| Model Building Tools | Programs (Coot, O) for interpreting density maps and building atomic models | Both Methods |

X-ray crystallography and single-particle cryo-EM represent two powerful, complementary approaches for determining macromolecular structures, each with distinct advantages and limitations rooted in their fundamental physical principles. X-ray crystallography, governed by Bragg's Law, continues to provide the highest resolution structures for samples that can form well-ordered crystals, remaining the most productive method in terms of total structures determined [2]. Single-particle cryo-EM has undergone a "resolution revolution" that now enables near-atomic resolution for many macromolecular complexes that resist crystallization, particularly membrane proteins, large complexes, and dynamic assemblies [1] [3].

The choice between techniques depends on the specific biological question, sample characteristics, and available resources. For well-behaved proteins that crystallize readily, X-ray crystallography remains the most efficient path to atomic resolution. For large, flexible, or heterogeneous complexes—particularly those difficult to crystallize—single-particle cryo-EM offers unparalleled advantages. Most significantly, these methods are increasingly used together in hybrid approaches that leverage their complementary strengths, such as docking high-resolution crystallographic structures into lower-resolution cryo-EM maps of larger complexes [1] [4].

As both technologies continue to advance, with crystallography pushing toward ever-higher resolutions and cryo-EM expanding its capabilities for smaller proteins and more complex heterogeneous samples, their synergistic application will undoubtedly drive future breakthroughs in understanding biological mechanisms and facilitating structure-based drug design.

Historical Context and the 'Resolution Revolution'

The field of structural biology, dedicated to elucidating the three-dimensional architecture of biological macromolecules, has undergone a profound transformation. For decades, X-ray crystallography stood as the undisputed cornerstone, responsible for the vast majority of structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). This landscape shifted dramatically with the advent of a "resolution revolution" in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), a technological leap that has redefined the possibilities of molecular visualization [10]. This revolution was primarily ignited by the introduction of direct electron detectors, which provided dramatically improved signal-to-noise ratios and enabled accurate correction of beam-induced motion, thereby unlocking near-atomic resolution for previously intractable targets [10]. Understanding the historical context and comparative capabilities of these two powerful techniques is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to determine the optimal strategy for their structural inquiries. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Historical Dominance of X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography has a long and storied history, originating in the early 20th century following Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen's discovery of X-rays and the subsequent demonstration of X-ray diffraction by crystals by Max von Laue [11]. The development of this technique is firmly rooted in Bragg's Law (nλ = 2dsinϑ), which describes the condition for constructive interference and enables the determination of atomic positions from a crystal's diffraction pattern [11]. Its pivotal role in biology was cemented by the determination of the DNA double helix structure by Watson, Crick, Franklin, and Wilkins [12].

For generations, X-ray crystallography has been the workhorse of structural biology. As of September 2024, it accounts for approximately 84% of all structures deposited in the PDB, a testament to its dominance and reliability [13]. This technique has been instrumental in countless scientific discoveries, from elucidating enzyme mechanisms and solving membrane protein structures to facilitating structure-based drug design, as exemplified by the development of inhibitors for the SARS-CoV-2 main protease [10].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in X-ray Crystallography

| Year | Milestone | Key Figures/Study | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Discovery of X-rays | Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen | Enabled the development of diffraction-based imaging. |

| 1912 | Demonstration of X-ray diffraction | Max von Laue | Proved crystals could diffract X-rays. |

| 1915 | Development of Bragg's Law | William Henry and William Lawrence Bragg | Provided the foundational equation for analyzing diffraction data. |

| 1953 | Structure of DNA | Watson, Crick, Franklin, Wilkins | Revolutionized understanding of genetic information storage. |

| 1958 | First protein structure (myoglobin) | Kendrew et al. | Opened the door to atomic-level protein visualization [10]. |

| 2011 | β2-adrenergic receptor structure | Rasmussen et al. | Breakthrough in membrane protein crystallography using lipidic cubic phase [10]. |

| 2020 | SARS-CoV-2 main protease structure | Zhang et al. | Critical for antiviral drug discovery during the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. |

The Cryo-EM Resolution Revolution

While cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has existed for decades, its potential was fully unleashed in the 2010s, an era often termed the "resolution revolution" [12]. This transformation was catalyzed by major technological advancements, most notably the introduction of direct electron detectors [10]. These detectors provided dramatically improved signal-to-noise ratios, accurate electron counting, and rapid frame rates, which enabled the correction of beam-induced motion—a critical barrier to achieving high resolution [10].

A landmark achievement demonstrating this new capability was the determination of the TRPV1 ion channel structure at near-atomic resolution, revealing how this protein detects heat and pain [10]. This structure, which was previously intractable, showcased cryo-EM's power for solving complex membrane protein structures without the need for crystallization. The profound impact of these developments was recognized with the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of cryo-EM [12].

The growth of the technique has been exponential. From contributing a negligible number of structures in the early 2000s, cryo-EM now accounts for a significant portion of new PDB deposits. In 2023, over 4,500 structures were solved by EM, representing nearly 32% of all releases that year [11]. This trend indicates that cryo-EM is poised to surpass X-ray crystallography as the most used method for determining new structures [9].

Objective Performance Comparison: X-ray Crystallography vs. Cryo-EM

A direct comparison of these two techniques reveals a complementary set of strengths and limitations, which are crucial for selecting the appropriate method for a given project. The following data synthesizes information from industry and academic sources to provide an objective performance comparison.

Table 2: Technical Comparison of X-ray Crystallography and Cryo-EM

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM (Single-Particle) | Supporting Data & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Atomic (often <1.5 Å) | Near-atomic to Atomic (1.5-4 Å for many structures) [10] | Cryo-EM has not yet reached the physical limits set by radiation damage [9]. |

| Sample Requirement | High-purity, homogeneous, crystallizable protein. Requires 5+ mg at ~10 mg/mL [13]. | High-purity, homogeneous protein. Requires a small amount (≤0.5 mg) at low concentrations (≥0.5 mg/mL) [13]. | Crystallization is the largest hurdle in X-ray crystallography [13]. |

| Sample State | Crystalline solid. | Vitrified solution (frozen-hydrated). | Cryo-EM studies molecules in a near-native state without crystallization [10]. |

| Molecular Weight | No inherent size limit, but crystal quality can be an issue for large complexes [13]. | Ideal for large complexes (>150 kDa), though smaller targets are becoming feasible. | Well-ordered crystals become more difficult to obtain as target size and complexity increase [13]. |

| Throughput | High for established crystal systems; slow and uncertain for novel targets. | Rapid for data collection once grids are optimized; processing is automated but computationally intensive. | X-ray crystallography remains the workhorse for high-throughput structure determination [13]. |

| Membrane Proteins | Challenging; requires special methods like Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP). Successful for many GPCRs [13]. | Excellent; no crystallization needed. Ideal for large, flexible complexes. | The TRPV1 ion channel structure is a prime example of cryo-EM's power for membrane proteins [10]. |

| Time Resolution | Millisecond range with advanced mix-and-quench or XFEL methods [14]. | Currently limited, but development of time-resolved cryo-EM is underway. | Non-photo-initiated mixing methods in crystallography achieve single-millisecond range [14]. |

| PDB Deposition (2023) | ~9,601 structures (66% of total) [11]. | ~4,579 structures (31.7% of total) [11]. | NMR accounted for 272 structures (1.9%) in 2023 [11]. |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in these structural biology techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application in X-ray Crystallography | Application in Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | A membrane mimetic matrix for stabilizing membrane proteins. | Used for crystallizing GPCRs and other integral membrane proteins [13]. | Not typically used. |

| Detergents | Solubilizes membrane proteins by mimicking the lipid environment. | Essential for purifying and crystallizing membrane proteins [13]. | Used for purifying membrane proteins prior to grid preparation. |

| Cryo-Protectants | Prevents ice crystal formation during vitrification. | Used for flash-cooling crystals prior to data collection at synchrotrons. | Essential for creating the vitreous ice layer that embeds the sample [12]. |

| Heavy Atom Solutions | Contains atoms with high electron numbers (e.g., Gold, Uranium, Platinum). | Soaked into crystals for experimental phasing (e.g., SAD/MAD) [13]. | Used for negative staining to quickly assess sample quality and distribution (not for high-res). |

| Gold Grids | Sample support for electron microscopy. | Not used. | Standard support film for cryo-EM sample grids. |

| 15N / 13C Isotopes | Stable isotopes incorporated into recombinant proteins. | Not required for standard crystallography. | Not required for standard single-particle cryo-EM. Essential for NMR and solid-state NMR [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Time-Resolved X-ray Crystallography via Mix-and-Quench

This protocol, enabling time resolution in the sub-10 ms range, is used to capture transient enzymatic states [14].

- Crystal Preparation: Grow microcrystals of the target biomolecule (e.g., lysozyme).

- Reaction Initiation (Mixing): Rapidly mix the crystal slurry with a substrate or ligand solution using a specialized instrument. This step initiates the enzymatic reaction.

- Thermal Quenching: After a precise, variable delay (e.g., from 8 ms to seconds), the reaction is halted by rapidly freezing the mixture with a cryogen. This step "traps" the structural state at that specific time point.

- Data Collection: The quenched sample is transferred to a synchrotron beamline for X-ray diffraction data collection. As demonstrated, this can require as few as one crystal per time point [14].

- Data Processing & Analysis: Diffraction data are indexed, integrated, and scaled. Structural models are then built and refined for each time point to create a molecular movie of the reaction.

Protocol 2: Single-Particle Cryo-EM Workflow

This is the standard workflow for determining high-resolution structures from vitrified protein samples [10] [12].

- Sample Vitrification:

- A purified protein solution (at ~0.5-3 mg/mL) is applied to an EM grid.

- The grid is blotted with filter paper to create a thin liquid film.

- The grid is rapidly plunged into a cryogen (typically liquid ethane), freezing the water in a vitreous (non-crystalline) state and embedding the protein particles in a thin layer of ice.

- Data Collection:

- The vitrified grid is loaded into a high-end cryo-electron microscope (e.g., Titan Krios) equipped with a direct electron detector.

- The microscope automatically collects thousands of "micrographs" (images) of the sample, with the electron beam set to a low dose to minimize radiation damage.

- Image Processing:

- Particle Picking: Individual protein particles are automatically identified and extracted from the micrographs.

- 2D Classification: Extracted particles are grouped into classes representing different views of the protein.

- 3D Reconstruction: A preliminary 3D model is generated, and iterative refinements are performed to align all particle images to the model, ultimately reconstructing a high-resolution 3D electron density map.

- Atomic Model Building:

- An atomic model is built into the refined electron density map, either de novo or by fitting and adjusting a known homologous structure.

- The model is stereochemically refined and validated against the map data.

Emerging Trends and Synergistic Integration

The future of structural biology lies not in the supremacy of a single technique, but in their strategic integration and the application of artificial intelligence. A powerful trend is the combination of time-resolved X-ray methods with cryo-EM to visualize molecular movies of biological processes [15]. For instance, mix-and-quench crystallography can capture short-lived intermediates, while cryo-EM can provide detailed snapshots of larger, more complex functional states.

Furthermore, AI and deep learning are revolutionizing both fields. AI-based tools like AlphaFold have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences [10]. These computational models are now being integrated directly into cryo-EM workflows, where they can serve as initial models for refinement, help in interpreting regions of low map quality, and even assess the local quality of a built structure [10] [16]. This AI integration is accelerating the exploration of protein structure-function relationships, directly impacting biomedical research and therapeutic development [10].

The "resolution revolution" in cryo-EM has fundamentally diversified the toolkit available to structural biologists, offering a powerful alternative to the long-dominant technique of X-ray crystallography. While crystallography remains the gold standard for high-throughput atomic-resolution structure determination of proteins that can be crystallized, cryo-EM excels at solving structures of large, flexible, and membrane-embedded complexes that defy crystallization. The choice between them is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is the most appropriate for a specific biological question. The most profound insights will increasingly come from the synergistic use of both methods, augmented by the predictive power of AI, to visualize the dynamic molecular machinery of life in unprecedented detail.

The field of structural biology is powered by three principal experimental techniques for determining the three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules: X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and electron microscopy (EM), notably cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the evolving market share and deposition statistics of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) is crucial for making informed decisions about which methodology to employ for their specific projects.

The PDB, the single global archive for three-dimensional structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, provides a clear window into the adoption rates and productivity of these techniques [17]. Historically, X-ray crystallography dominated the landscape, but recent years have witnessed a dramatic shift. The "resolution revolution" in cryo-EM, marked by significant improvements in detector technology and image processing software, has positioned it as a powerful competitor [3] [10]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these techniques' current market share based on the latest PDB deposition statistics, offering a snapshot of the modern structural biology toolkit.

Quantitative Analysis of PDB Deposition Trends

The growth in structures released to the PDB has been exponential, reflecting the increasing importance of structural biology in biomedical research. The following table summarizes the total number of structures released annually over recent years, providing context for the methodological shifts discussed later.

Table 1: Total Number of PDB Structures Released Annually (2020-2025)

| Year | Total Number of Structures Released |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 13,982 [18] |

| 2021 | 12,569 [18] |

| 2022 | 14,253 [18] |

| 2023 | 14,447 [18] |

| 2024 | 15,293 [18] |

| 2025 | 15,689 [18] |

A breakdown of the deposition statistics by experimental method reveals a dynamic and shifting landscape. The following table synthesizes the most current data available on the market share of the three primary techniques.

Table 2: Market Share of Primary Structure Determination Techniques in the PDB

| Technique | Historical Context | Recent Annual Share (2023-2024) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Dominant method; >86% of all deposited structures [17] | ~66% of new structures in 2023 [17] | Atomic resolution; well-established workflows; high throughput [17] [10] |

| Cryo-EM | Almost negligible in early 2000s [17] | ~31.7% of new structures in 2023 [17]; up to 40% of new deposits by 2023-2024 [17] | No crystallization needed; ideal for large complexes and membrane proteins [3] [19] |

| NMR | Consistently a smaller contributor [17] | ~1.9% of new structures in 2023 [17] | Studies proteins in solution; probes dynamics and flexibility [17] [10] |

Regional Deposition Analysis

Structural biology is a global endeavor, and the geographic distribution of PDB depositions highlights regional research focus and capacity. The data below, sourced from the wwPDB, shows the number of structures deposited by principal investigators based on their geographic location over a recent five-year period.

Table 3: PDB Depositions by Geographic Region (2020-2024)

| Year | North America | Europe | Asia | South America | Australia/New Zealand | Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 4,757 [18] | 6,167 [18] | 3,379 [18] | 157 [18] | 409 [18] | 9 [18] |

| 2021 | 4,795 [18] | 4,741 [18] | 4,083 [18] | 125 [18] | 491 [18] | 17 [18] |

| 2022 | 5,347 [18] | 5,160 [18] | 4,663 [18] | 87 [18] | 443 [18] | 11 [18] |

| 2023 | 4,670 [18] | 5,669 [18] | 5,297 [18] | 92 [18] | 365 [18] | 11 [18] |

| 2024 | 5,861 [18] | 5,875 [18] | 6,617 [18] | 82 [18] | 388 [18] | 10 [18] |

This data indicates a robust and growing structural biology effort in Asia, which has now surpassed North America and Europe in the number of annual depositions [18]. This growth correlates with significant regional investments in research infrastructure, including cryo-EM facilities [20] [21] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol for Single-Particle Cryo-EM

Single-particle analysis is the workhorse of modern cryo-EM, allowing for the determination of high-resolution structures from millions of individual particle images [3].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Cryo-EM

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Cryo-EM Grids | Tiny mesh grids that hold the vitrified sample for imaging under the electron beam [3]. |

| Vitrification Agents (e.g., liquid ethane) | Used to flash-freeze the aqueous sample so that it forms a glassy (vitreous) ice instead of crystalline ice, which would damage the sample [3]. |

| Direct Electron Detector | A critical camera technology that directly counts incoming electrons with high sensitivity, enabling the "resolution revolution" [10]. |

| Image Processing Software (e.g., RELION, cryoSPARC) | Algorithms used for the complex tasks of 2D classification, 3D reconstruction, and refinement of the final atomic model [3] [19]. |

Workflow Steps:

- Sample Preparation: The purified biological sample is applied to a specially designed grid [3].

- Vitrification: The grid is plunged into a cryogen (like liquid ethane) cooled by liquid nitrogen. This rapid freezing immobilizes the molecules in a thin layer of vitreous ice, preserving their native state [3].

- Data Collection: The vitrified grid is loaded into a cryo-electron microscope (e.g., a Titan Krios or Talos Arctica). The microscope bombards the sample with electrons, and images are collected by a direct electron detector from different orientations [3] [10].

- Image Processing: This computationally intensive step involves several sub-steps:

- Particle Picking: Millions of individual particle images are automatically selected from the micrographs.

- 2D Classification: Particles are grouped into classes representing similar views.

- 3D Reconstruction: A initial model is generated and iteratively refined to produce a high-resolution 3D electron density map.

- Atomic Model Building: Researchers fit and refine an atomic model of the protein or complex into the final electron density map [10].

The following diagram illustrates this complex workflow.

Protocol for X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography remains a dominant method due to its ability to provide atomic-resolution data, though it requires the often-challenging step of growing high-quality crystals [17] [10].

Workflow Steps:

- Crystallization: The purified macromolecule is induced to form a highly ordered crystal through extensive screening of conditions (e.g., pH, precipants) [17].

- Data Collection: A single crystal is exposed to a high-intensity X-ray beam (e.g., from a synchrotron source). The crystal diffracts the X-rays, producing a characteristic pattern of spots on a detector [17].

- Data Processing: The diffraction pattern is processed to determine the amplitude of the diffracted waves. The critical "phase problem" must be solved using methods like molecular replacement or experimental phasing (e.g., SAD/MAD) [17].

- Electron Density Map Calculation: The amplitudes and phases are combined to calculate an electron density map [17].

- Model Building and Refinement: An atomic model is built into the electron density and iteratively refined to improve its fit to the experimental data [17] [10].

The workflow for X-ray crystallography is shown in the diagram below.

The quantitative data from the PDB reveals a structural biology field in the midst of a significant transformation. While X-ray crystallography continues to be the most prolific method in terms of total annual deposits, its historical dominance is steadily being challenged. The meteoric rise of cryo-EM is the most notable trend, with its share of new deposits growing from nearly zero to roughly one-third of all new structures in less than a decade [17]. This shift is a direct result of the technical advancements that constituted the "resolution revolution" [3] [10].

This methodological evolution has profound implications for researchers and drug development professionals. The choice of technique is no longer default but strategic. X-ray crystallography remains unparalleled for high-throughput studies of proteins that readily form crystals and for achieving the very highest resolutions [17] [10]. In contrast, cryo-EM has become the go-to method for visualizing large, flexible, or heterogeneous complexes that have resisted crystallization, such as membrane proteins, ribosomes, and viral capsids [3] [19]. Its ability to capture multiple conformational states within a single sample is particularly valuable for understanding functional mechanisms [10]. NMR spectroscopy, while contributing a smaller fraction of new structures, retains its unique niche in studying protein dynamics and small, soluble proteins in their native, solution-state environment [17] [10].

Looking forward, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning is poised to be the next disruptive force. AI tools like AlphaFold are already revolutionizing computational structure prediction and are being integrated into cryo-EM and crystallography workflows to accelerate model building and refinement [10] [19]. Furthermore, the robust growth in depositions from Asia signals a continued globalization of structural biology, which will likely fuel further innovation and discovery [18]. For the scientific community, this means an increasingly powerful and diverse toolkit to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of life and disease, ultimately accelerating the pace of drug discovery and therapeutic development.

In structural biology, the path to elucidating the three-dimensional architecture of biomolecules hinges critically on sample preparation. This initial phase determines the success of high-resolution techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). The core methodological divide lies between two distinct preparation philosophies: crystallization, which arranges molecules into a periodic lattice, and vitrification, which flash-freees molecules in a near-native state within amorphous ice [22] [4]. This guide provides a detailed, experimental data-driven comparison of these two foundational approaches, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select and optimize the correct path for their specific biological questions and samples.

The choice between these methods is not merely a technicality; it fundamentally shapes the type of biological information that can be retrieved. Crystallization can yield atomic-resolution snapshots of highly ordered systems, while vitrification excels at capturing the structural heterogeneity and dynamic states of complex assemblies in their native environment [23] [4]. Understanding the requirements, challenges, and opportunities presented by each method is therefore paramount for the efficient allocation of resources and the ultimate success of structural projects.

Crystallization: The Ordered Lattice

Principle and Workflow

Crystallization is the process of inducing a purified macromolecular solution to form a highly ordered, three-dimensional crystal lattice. The principle relies on carefully bringing the sample to a state of supersaturation, typically by gradually removing water or adding precipitants, which drives molecules out of solution and into a growing crystal where they form specific, repeating contacts [24]. A successful crystal acts as an amplifying scaffold, allowing the collective scattering of X-rays to produce a strong, interpretable diffraction pattern [23].

The following workflow outlines the standard steps for a crystallization experiment, from initial sample preparation to data collection.

Key Reagents and Experimental Protocols

Successful crystallization requires meticulous biochemical preparation and the use of specific reagents to drive and control the process [24].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Crystallization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) of various molecular weights, Ammonium sulfate, 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) | Drives the sample into a supersaturated state by excluding water or competing for solvation, promoting molecular interactions for lattice formation [24]. |

| Buffers | HEPES, Tris, MES (non-phosphate based) | Maintains sample stability at a specific pH, ideally near the protein's isoelectric point (pI) to facilitate crystal contacts [24]. |

| Additives & Salts | Monovalent and divalent salts (e.g., NaCl, MgCl₂), co-factors, substrates | Can stabilize specific conformations, mediate intermolecular contacts, or reduce surface entropy to promote ordered packing [24]. |

| Chemical Reductants | Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Prevents cysteine oxidation over the extended timescale (days to months) of crystal growth, maintaining sample homogeneity [24]. |

| Crystallization Plates & Robots | 96-well sitting-drop or hanging-drop plates, Mosquito/Dragonfly liquid handlers | Enables high-throughput screening of thousands of chemical conditions with nanoliter-volume drops, conserving precious sample [13]. |

A standard vapor diffusion protocol (sitting-drop method) involves:

- Sample Preparation: The target biomolecule is purified to >95% homogeneity and must be monodisperse, as assessed by techniques like size-exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) or dynamic light scattering (DLS) [24]. Typical starting concentrations are 5-20 mg/mL for soluble proteins.

- Drop Setup: Using a liquid-handling robot, nanoliter volumes of the protein sample and crystallization cocktail (precipitant solution) are mixed in a 1:1 to 2:1 ratio on a plate.

- Incubation: The plate is sealed, and the drop is allowed to equilibrate against a larger reservoir of the precipitant solution. Water vapor slowly transfers from the drop to the reservoir, gradually increasing the concentration of both the protein and precipitant in the drop, ideally leading to nucleation and crystal growth [13] [24].

- Optimization: Initial crystal "hits" are optimized by fine-tuning parameters like pH, precipitant concentration, and temperature, or by using techniques like seeding [13].

Technical Requirements and Sample Considerations

Crystallization imposes stringent requirements on sample quality and properties. The following table summarizes the typical prerequisites and the associated challenges, particularly for difficult targets like membrane proteins.

Table 2: Crystallization Sample Requirements and Challenges

| Parameter | Ideal Requirement | Common Challenges & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Purity & Homogeneity | >95% pure, monodisperse [24] | Flexible regions or isoforms cause heterogeneity. Solution: Construct engineering using AlphaFold predictions to remove flexible loops [24]. |

| Stability | High, over days to months | Sample degradation during screening. Solution: Addition of stabilizing ligands or substrates to the buffer [24]. |

| Concentration | High (e.g., 5-20 mg/mL for soluble proteins) [13] [25] | Concentration-dependent aggregation. Solution: Pre-crystallization tests to determine the optimal concentration window [24]. |

| Sample Amount | Relatively large (typically >5 mg) [25] | Low-yield expression systems. Solution: Advanced expression systems and miniaturized screening with liquid handlers. |

| Membrane Proteins | Requires detergents or lipidic cubic phase (LCP) [13] | Detergents interfere with crystal contacts. Solution: LCP crystallization provides a more native lipid environment and has been key for GPCR structures [13] [10]. |

Vitrification: Trapping Native State

Principle and Workflow

Vitrification is the rapid freezing of an aqueous sample to form a non-crystalline, glass-like state of ice. This process, which cools the sample to below -150 °C within milliseconds, traps biological particles in a near-native state, preserving their natural conformation and preventing the damaging formation of crystalline ice [22]. In cryo-EM, these vitrified samples are then imaged with an electron beam, and thousands of individual particle images are computationally combined to determine a 3D structure [22] [23].

The workflow for single-particle analysis (SPA) cryo-EM involves several key steps from sample preparation to high-resolution reconstruction.

Key Reagents and Experimental Protocols

The vitrification workflow, while faster than crystallization, requires specialized reagents and equipment to ensure optimal sample preservation [22] [25].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vitrification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Support Grids | Holey carbon grids (Quantifoil, C-flat), Graphene-based grids (e.g., GraFuture) | Provides a support film with holes where the sample is suspended in a thin layer of vitreous ice. Graphene grids reduce background noise and mitigate preferred orientation [25]. |

| Cryogens | Liquid ethane, liquid ethane/propane mixture | Has high thermal conductivity to enable cooling rates fast enough to bypass water crystal formation and achieve vitrification [22]. |

| Buffer Components | Low-salt buffers, detergents for membrane proteins | Maintains sample stability and monodispersity during grid preparation. Low salt concentrations (<300 mM) are preferred to reduce background noise [25]. |

| Vitrification Robots | Vitrobot (Thermo Fisher), GP2 (Leica) | Automated instruments that control key variables like blotting time, force, and humidity, ensuring reproducible and high-quality vitreous ice [22]. |

A standard plunge-freezing protocol involves:

- Sample Application: A small volume (typically 2-5 µL) of the purified sample at a concentration of ≥ 0.5-2 mg/mL is applied to a glow-discharged EM grid [25].

- Blotting: Excess liquid is removed by pressing filter paper against the grid for a few seconds, leaving a thin film of sample spanning the holes of the support film.

- Plunging: The grid is rapidly plunged into a container of liquid ethane cooled by a surrounding liquid nitrogen dewar. This rapid heat transfer vitrifies the thin film of water [22].

- Storage and Imaging: The vitrified grid is stored in liquid nitrogen and transferred under cryogenic conditions to the electron microscope for data collection.

Technical Requirements and Sample Considerations

Vitrification is less demanding than crystallization in terms of sample amount and order, but it has its own unique set of requirements and challenges related to the behavior of particles in thin ice.

Table 4: Vitrification Sample Requirements and Challenges

| Parameter | Ideal Requirement | Common Challenges & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Purity & Homogeneity | ≥ 90% pure [25] | Sample heterogeneity can be addressed computationally. Solution: 2D and 3D classification can separate out different conformational states or complexes from a single dataset [22]. |

| Stability | Short-term (minutes) during grid preparation | Denaturation at the air-water interface. Solution: Use of additives like detergents or specialized grids to shield particles [25]. |

| Concentration | Lower than crystallization (e.g., ≥ 0.5-2 mg/mL) [25] | Finding the right particle density. Solution: Empirical testing of concentration and blotting conditions to achieve a monolayer of well-separated particles. |

| Sample Amount | Minimal (e.g., ~100 µL at 0.5-2 mg/mL) [25] | Often only a few micrograms of protein are consumed per grid, making it suitable for low-yield targets [26]. |

| Particle Size | Optimal for >100 kDa complexes, possible down to ~50 kDa [23] [25] | Small proteins produce weak scattering. Solution: Use of high-end microscopes with direct electron detectors and advanced processing software [10] [25]. |

| Buffer Compatibility | Low salt (≤300 mM), low volatile solvents [25] | Buffer components can form crystalline ice or high background. Solution: Buffer exchange into compatible buffers prior to grid preparation. |

Comparative Analysis: Data-Driven Decision Making

Direct Comparison of Key Parameters

Choosing between crystallization and vitrification requires a pragmatic assessment of sample properties and project goals. The following table provides a side-by-side comparison of quantitative and qualitative metrics derived from experimental data and standard protocols.

Table 5: Direct Comparison of Crystallization and Vitrification for Structural Analysis

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography (Crystallization) | Single-Particle Cryo-EM (Vitrification) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Requirement | High-quality, ordered 3D crystals | Monodisperse, purified particles in thin ice |

| Typical Sample Amount | >5 mg (soluble protein) [25] | ~0.1-0.2 mg (can be lower) [23] |

| Sample Concentration | High (e.g., >10 mg/mL) [25] | Moderate (e.g., ≥ 2 mg/mL) [25] |

| Molecular Size Suitability | Optimal <100 kDa [23] | Optimal >100 kDa, down to ~50 kDa demonstrated [23] [25] |

| Handling of Flexibility | Poor; flexible regions often disordered or engineered out [24] | Good; can often resolve multiple conformational states from one dataset [23] [4] |

| Typical Timeline | Weeks to months (crystal optimization) [23] | Weeks (faster initial structure) [23] |

| Maximum Resolution | Sub-1.0 Å possible [23] | ~1.4 Å demonstrated, typically 2.5-3.5 Å for complexes [25] |

| Ideal Application | Atomic-level detail of stable, crystallizable molecules | Large, flexible complexes, membrane proteins in near-native states [4] [10] |

Application Scenarios and Method Selection

The comparative advantages of each technique make them uniquely suited for specific biological problems.

Membrane Protein Structural Analysis: For crystallography, membrane proteins often require extensive engineering, detergent screening, or the use of lipidic cubic phase (LCP) methods to form crystals, which can lock the protein into a single conformation [13]. In contrast, vitrification allows membrane proteins to be embedded in lipid nanodiscs or detergent micelles and studied in multiple functional states without the constraints of a crystal lattice, providing insights into mechanisms like gating and ligand binding [23] [10].

Large Protein Complex Studies: Crystallography becomes increasingly challenging with the size and complexity of assemblies, as forming well-ordered crystals is difficult. Vitrification excels here, with no upper size limit, making it the preferred method for massive complexes like ribosomes, viruses, and the nuclear pore complex [23] [10].

Dynamic Structure Visualization: Crystallography provides a single, high-resolution snapshot of the most stable conformation. Vitrification, combined with computational 3D classification, can resolve multiple conformational intermediates from a heterogeneous sample, effectively creating a "movie" of molecular dynamics from a single preparation [23] [4].

The "sample preparation divide" between crystallization and vitrification represents a fundamental fork in the road for structural biologists. Crystallization demands high homogeneity and order to produce a single, atomic-resolution snapshot, while vitrification embraces complexity and flexibility to visualize biomolecules in a near-native state. There is no single "best" method; the choice is dictated by the biological question, the properties of the target molecule, and available resources.

The future of structural biology lies not in the exclusive use of one technique over the other, but in their strategic integration. Medium-resolution cryo-EM maps can provide initial phases for solving crystal structures of challenging targets, a practice known as molecular replacement [4]. Furthermore, the rise of integrative modeling, which combines data from cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, NMR, and other biophysical techniques, promises a more holistic and dynamic understanding of molecular machines. By mastering both crystallization and vitrification, researchers can leverage the unique strengths of each to illuminate the intricate architecture of life at the atomic level.

Workflow Deep Dive: From Sample to Atomic Model with X-ray and Cryo-EM

X-ray crystallography has long been the cornerstone of structural biology, responsible for determining over 86% of the structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [27]. This dominance is now being challenged by the rapid ascent of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which accounted for nearly 40% of new structure deposits by 2023-2024 [27]. Some projections even suggest that single-particle cryo-EM is poised to surpass X-ray crystallography as the most used method for experimentally determining new structures [9]. Despite this shift, X-ray crystallography remains an indispensable tool, especially for obtaining atomic-resolution structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes, providing critical insights for drug discovery and rational drug design [28] [10].

The fundamental strength of crystallography lies in its ability to reveal molecular structures at atomic resolution, often better than 1.5 Å, enabling the precise visualization of drug-target interactions and enzyme active sites [25]. However, the technique faces a significant bottleneck: the requirement for high-quality, well-ordered crystals, which can be notoriously difficult to obtain for many biologically important targets, particularly membrane proteins and large, flexible complexes [27] [10]. It is within this context of methodological competition and complementarity that we examine the detailed workflow of X-ray crystallography, from crystallization to phasing, while objectively comparing its capabilities and limitations against cryo-EM approaches.

The Crystallization Workflow: From Protein to Crystal

Sample Preparation and Pre-crystallization Assessment

The journey to a high-resolution structure begins with the production of a pure, monodisperse, and stable protein sample. Table 1 outlines the typical sample requirements for successful crystallization. For standard crystallography, protein purity must exceed 95%, with concentrations typically greater than 10 mg/ml and a total sample amount of more than 5 mg [28] [25]. These requirements are generally more stringent than those for cryo-EM Single Particle Analysis (SPA), which can often work with concentrations as low as 2 mg/ml and purity levels around 90% [25].

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Protein Crystallization

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose in Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-purity protein (>95%) | Ensures homogeneous nucleation and crystal growth; reduces amorphous aggregation. |

| Crystallization screens (e.g., Hampton Research) | Provides thousands of pre-formulated conditions to identify initial crystal hits by varying precipants, pH, and salts [28]. |

| Precipitants (PEG, Ammonium Sulfate) | Drives protein out of solution in a controlled manner to promote crystal formation [28]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Assesses sample monodispersity and detects aggregates that interfere with crystallization [28]. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | Determines optimal buffer conditions and protein stability for crystallization [28]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Removes aggregates and polydisperse populations to improve crystal quality [28]. |

Before crystallization trials, the protein sample undergoes rigorous biophysical characterization. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) assesses monodispersity, while differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) determines optimal buffer conditions and protein stability [28]. For proteins with suspected flexibility, NMR spectroscopy can be used to verify folding status via HSQC fingerprint analysis, identifying unfolded regions or flexible domains that might prevent crystal formation [28].

Crystallization Strategies and Optimization

The crystallization process itself involves screening hundreds to thousands of conditions to identify initial crystal hits. Commercial screens systematically vary critical parameters including buffer type and pH, ionic strength, salts, and precipitant type and concentration [28]. The most common precipitants are polyethylene glycol (PEG) and ammonium sulfate.

Once initial conditions are identified, extensive optimization follows to improve crystal size and quality. This may involve fine-tuning the pH, precipitant concentration, or adding small molecule additives that enhance crystal packing [28]. For membrane proteins, specialized techniques such as the lipidic cubic phase (LCP) method have been crucial for success, enabling the determination of groundbreaking structures like the β2-adrenergic receptor [10].

The timeline for crystallization screening and optimization typically ranges from 3-6 weeks, though particularly challenging targets may require significantly more time and resources [28]. This represents a key differentiator from cryo-EM, which can often proceed more directly from sample to data collection without the crystallization bottleneck.

Data Collection: Harnessing Synchrotron Radiation

From Crystal to Diffraction Pattern

Once suitable crystals are obtained, they are cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen to minimize radiation damage during X-ray exposure [28]. The crystals are then exposed to high-intensity X-ray beams, traditionally at synchrotron facilities, though laboratory sources are also used for preliminary characterization.

Synchrotron radiation provides several critical advantages for data collection, as outlined in Table 2. The high brilliance of modern beamlines allows data collection from much smaller crystals than previously possible [28]. The tunable wavelengths enable experimental phasing methods like multiple-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD), while the beam focus and stability are essential for collecting high-resolution data [28] [29].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of X-ray Crystallography and Cryo-EM

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM Single Particle Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Atomic resolution (often better than 1.5 Å) [25] | Near-atomic resolution (typically 1.8-3.5 Å) [25] [10] |

| Sample Requirement | ≥10 mg/ml, >5 mg total, >95% purity [25] | ≥2 mg/ml, ≥100 μL volume, ≥90% purity [25] |

| Key Limiting Step | Crystal growth and quality [27] [10] | Sample preparation and preferred orientation [25] |

| Molecular Weight Range | No upper limit in theory, but crystallization becomes challenging for very large complexes [27] | Optimal for complexes >150 kDa; can go lower with specialized grids [25] |

| Time to Structure (after sample) | Weeks to months (crystallization dependent) [28] | Days to weeks (no crystallization needed) [30] |

| PDB Deposition Share (2023) | ~66% of structures [27] | ~32% of structures and growing [27] |

| Membrane Protein Suitability | Challenging; requires specialized methods like LCP [10] | Excellent; particularly suited for large membrane complexes [10] |

Fourth-generation synchrotrons, such as MAX IV in Sweden, represent the cutting edge in crystallography data collection. These facilities feature multi-bend achromat (MBA) technology that significantly reduces emittance, resulting in increased brightness and coherence of the X-ray beam [29]. This enables faster data collection, opening possibilities for crystallography to be used as a screening method in drug discovery [29].

Emerging Approaches: Serial Crystallography

A significant advancement in data collection methods is the emergence of serial crystallography approaches. This technique involves collecting diffraction patterns from thousands of microcrystals sequentially, which is particularly valuable for systems that only produce microcrystals, such as many membrane proteins [29]. Serial methods also enable time-resolved studies and data collection at room temperature, capturing proteins in more physiological states [31] [29].

Recent work on human cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) exemplifies the power of room-temperature serial crystallography. This approach revealed better-defined loops compared to cryo-temperature structures, providing insights into the dynamic properties of this key drug-metabolizing enzyme [31].

Phasing: Solving the Phase Problem in Crystallography

Molecular Replacement and Experimental Phasing

A fundamental challenge in crystallography is the "phase problem" - while diffraction patterns provide intensity information, the phase information is lost during measurement but essential for calculating electron density maps [28]. Two primary approaches address this challenge:

Molecular Replacement (MR) has become the most common phasing method, particularly with the rise of AlphaFold and other AI-based structure prediction tools [29]. MR uses a known homologous structure (generally with sequence identity above 40-50%) as a search model to obtain initial phase information [28] [27]. The availability of accurate computational models has made MR increasingly successful, reducing the need for experimental phasing.

Experimental Phasing methods remain essential when suitable search models are unavailable. The most common approach involves introducing anomalous scatterers, typically by producing selenomethionine (SeMet)-labeled proteins [28]. Techniques like Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD) and Multiple-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD) exploit the anomalous scattering properties of these incorporated atoms to solve the phase problem [28] [27].

The Growing Role of Computational Methods

The integration of computational methods has dramatically transformed phasing and model building. AlphaFold models are increasingly used as search models for molecular replacement, particularly for targets without close experimental homologs [10]. Furthermore, automated model building and refinement algorithms have significantly accelerated the structure determination process.

Recent advances in automated phase mapping of high-throughput X-ray diffraction data demonstrate how encoding domain-specific knowledge of crystallography, thermodynamics, and materials science into optimization algorithms can solve complex phase analysis challenges [32]. While developed for materials science, these approaches illustrate the growing power of computational methods in crystallographic analysis.

Integrated Workflow and Comparative Visualization

The complete X-ray crystallography workflow integrates multiple steps from gene to structure, with parallel developments in cryo-EM offering complementary approaches for structural biologists. The following diagram illustrates this integrated pathway and its relationship to cryo-EM methodologies.

Integrated Structural Biology Workflows: X-ray Crystallography and Cryo-EM Pathways

X-ray crystallography continues to evolve with advancements in serial crystallography, brighter light sources, and more powerful computational methods [29]. However, its requirement for high-quality crystals remains a significant constraint for many biologically important targets. In contrast, cryo-EM has demonstrated remarkable capabilities for studying large complexes, membrane proteins, and multiple conformational states without crystallization [10].

The most powerful approach for modern structural biology lies in the integration of these complementary techniques. X-ray crystallography provides unparalleled resolution for amenable targets, offering atomic-level details critical for understanding enzyme mechanisms and drug binding [25] [10]. Meanwhile, cryo-EM tackles challenging complexes that defy crystallization, capturing functional states in near-native environments [30] [10]. This methodological synergy, enhanced by AI-based structure prediction, ensures that X-ray crystallography will remain a vital component of the structural biology toolkit, even as cryo-EM continues its exponential growth [9] [10].

For drug development professionals, the choice between techniques should be guided by the specific research question, target properties, and available resources. X-ray crystallography excels for atomic-resolution ligand binding studies when crystals can be obtained, while cryo-EM offers a path forward for intractable targets that have long resisted crystallization efforts. The future of structural biology lies not in the dominance of a single technique, but in the strategic application of multiple complementary methods to illuminate the molecular mechanisms of life and disease.

Structural biology has been transformed by two powerful techniques: cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography. While X-ray crystallography has long been the "gold standard" for determining atomic-resolution structures, cryo-EM has experienced a "resolution revolution" that now enables near-atomic resolution for many biologically significant complexes [4] [10]. These methods are not competing technologies but rather complementary tools that can work together for more complete structural insights [4] [1].

X-ray crystallography requires growing well-ordered three-dimensional crystals and analyzing their diffraction patterns [4] [33]. Its remarkable precision (routinely finer than 2 Å) reveals intimate atomic architecture but faces challenges with crystallization of membrane proteins, large complexes, and dynamic systems [4] [33]. In contrast, cryo-EM studies molecules in near-native states without crystallization by flash-freezing samples in thin ice layers and computationally processing thousands of individual particle images [4] [33]. This flexibility makes it particularly valuable for visualizing large macromolecular complexes, membrane proteins, and multiple conformational states [33].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these techniques, with detailed examination of the cryo-EM single-particle analysis workflow from sample preparation to high-resolution reconstruction, contextualized against traditional crystallographic approaches.

Technical Comparison: Fundamental Principles and Applications

Key Differences in Physical Principles and Output

Table 1: Fundamental methodological differences between Cryo-EM and X-ray Crystallography

| Aspect | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Radiation Source | High-energy electrons [1] | X-ray photons [4] |

| Sample State | Vitrified solution (near-native state) [33] | Well-ordered 3D crystal lattice [4] |

| Primary Interaction | Coulomb potential of atoms [1] | Electron clouds [4] |

| Information Recorded | 2D particle projections [4] | Diffraction pattern (Bragg reflections) [4] |

| Key Challenge | Low signal-to-noise ratio [34] | Phase problem [4] |

| Primary Output | 3D electron density map [35] | Electron density map [4] |

Performance Characteristics and Sample Requirements

Table 2: Practical performance comparison and sample requirements

| Parameter | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution Range | 2.5-4.0 Å [33] | 1.0-2.5 Å (often sub-1Å possible) [33] |

| Optimal Molecular Size | >100 kDa [33] | <100 kDa [33] |

| Sample Amount Required | 0.1-0.2 mg [33] | >2 mg typically [33] |

| Sample Purity Requirements | Moderate heterogeneity acceptable [33] | High homogeneity required [33] |

| Typical Timeline | Weeks [33] | Weeks to months [33] |

| Data Collection Time | Hours to days [33] | Minutes to hours [33] |

| Best Applications | Membrane proteins, large complexes, flexible assemblies [33] | Soluble proteins, small molecules, stable constructs [33] |

The Cryo-EM Single-Particle Analysis Workflow

The cryo-EM single-particle analysis workflow comprises three major stages: grid preparation, imaging, and computational reconstruction. Each stage contributes critically to the final resolution and quality of the determined structure.

Stage 1: Cryo-EM Grid Preparation

Grid preparation, or vitrification, involves flash-freezing aqueous samples to preserve native structure in vitreous ice [36].

Experimental Protocol: Plunge Freezing

Grid Selection and Treatment: TEM grids (typically 300-400 mesh) with holey carbon support films are selected. Grids are cleaned with organic solvents (acetone, ethyl acetate, or chloroform) and treated with glow-discharging to make the surface hydrophilic [35]. For challenging samples, grids may be coated with polylysine or functionalized graphene to improve particle distribution [36].

Sample Application and Blotting: A few microliters of purified sample are applied to the grid. Filter paper is used to blot away excess liquid, leaving an extremely thin aqueous film (typically 10-100 nm thick) [36]. Parameters like blot time, force, and humidity are controlled to optimize ice thickness [36].

Vitrification: The blotted grid is rapidly plunged into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen. This rapid freezing (~10⁶ K/s) prevents ice crystallization, preserving samples in a vitreous, glass-like state that maintains native structure [35].

Key Challenges and Optimization Strategies:

- Orientation Bias: Particles may adopt limited views due to interactions with the air-water interface. Solutions include adding mild detergents, using supporting films (ultrathin carbon, graphene), or collecting data with a tilted stage [36].

- Particle Partitioning: Particles may fail to enter holes. Optimization strategies include chemical treatments, multiple application rounds, or affinity grids with specialized coatings [36].

- Ice Contamination: Grids must be maintained below -170°C to prevent crystalline ice formation [35].

Stage 2: Cryo-EM Imaging

Imaging occurs in a transmission electron microscope operating at 200-300 kV [35]. Images are collected under low-dose conditions (~1-20 e⁻/Ų) to minimize radiation damage [37].

Experimental Protocol: Data Collection

Microscope Setup: The cryo-holder transfers the vitrified grid into the microscope column. Alignment ensures coherent illumination, and the low-dose system limits electron exposure [35].

Image Acquisition: Micrographs are recorded using direct electron detectors. Movies (typically 20-40 frames) capture beam-induced motion that can be corrected computationally [10]. Multiple micrographs are collected from different grid areas [35].

Contrast Formation Mechanisms:

Biological samples are weak phase objects that produce minimal amplitude contrast. Instead, most usable signal comes from phase contrast, generated by intentional defocusing to create interference between scattered and unscattered electron waves [37]. The weak phase object approximation simplifies computational processing by modeling the exit wave as the sum of unscattered and scattered waves [37].

Stage 3: Image Processing and 3D Reconstruction

This computationally intensive stage transforms 2D projections into 3D density maps [35].

Experimental Protocol: Image Processing Workflow

Pre-processing: Movie frames are motion-corrected to compensate for beam-induced drift [10]. The contrast transfer function (CTF) is estimated and corrected to account for microscope optics [35].

Particle Picking: Hundreds of thousands to millions of individual particle images are extracted from micrographs. Traditional methods use template matching, while modern approaches employ deep learning (e.g., DeepEM convolutional neural networks) for template-free particle selection [34].

2D Classification: Extracted particles are classified into 2D averages to remove non-particle images, contaminants, and poor-quality particles [35].

Initial Model Generation: An initial 3D model is created using random conical tilt, common lines, or model-based approaches [35].

3D Reconstruction: Iterative refinement aligns particles against projections of the 3D model and reconstructs the density map. For symmetric particles like viruses, symmetry constraints (e.g., icosahedral) improve resolution [35].

Validation and Sharpening: Resolution is estimated using gold-standard Fourier shell correlation. Maps are sharpened to correct for attenuation at high resolution [35].

Visual workflow comparing cryo-EM single-particle analysis with X-ray crystallography. The cryo-EM pathway (red) begins with vitrification of purified samples, while crystallography (gray, dashed) requires crystal formation. Both converge at atomic model building.

Integrated Applications in Structural Biology

The complementary strengths of cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography make them powerful when combined. Two integrative approaches are particularly valuable:

Hybrid Modeling: Medium-resolution cryo-EM maps (4-10 Å) provide the overall architecture of complexes, into which high-resolution X-ray structures of individual components can be docked [1]. Software packages like Situs, EMfit, and UCSF Chimera perform rigid-body docking, while Flex-EM and MDFF enable flexible fitting [1]. This approach revealed the architecture of the yeast RNA exosome complex by docking crystal structures of human core complexes into cryo-EM maps [1].

Molecular Replacement for Phasing: Cryo-EM maps can provide initial models for molecular replacement, solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography [4]. This is particularly valuable for large complexes where traditional phasing methods fail [4].

Table 3: Research reagent solutions for cryo-EM single-particle analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Grid Materials | Quantifoil grids, C-flat grids, Graphene oxide grids [36] | Support films with patterned holes or continuous surfaces for sample application |

| Grid Treatment | Glow discharge systems (Quorum SC7620), polylysine solution [35] | Modify surface properties to control hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity and particle adhesion |