Beyond PICADAR: Addressing Diagnostic Gaps and False Negatives in Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

This article examines the significant limitations of the PICADAR predictive tool in identifying Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), particularly its concerning false-negative rates in patients without classic laterality defects or hallmark...

Beyond PICADAR: Addressing Diagnostic Gaps and False Negatives in Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Abstract

This article examines the significant limitations of the PICADAR predictive tool in identifying Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), particularly its concerning false-negative rates in patients without classic laterality defects or hallmark ultrastructural abnormalities. Recent evidence reveals PICADAR's sensitivity can be as low as 59-61% in these subgroups, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment. We explore the pathophysiological and genetic basis for these limitations, evaluate complementary diagnostic methodologies including advanced genetic testing and high-speed video microscopy, and propose optimized, integrated diagnostic algorithms. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides critical insights for developing next-generation diagnostic strategies and designing more inclusive clinical trials that account for PCD's full phenotypic spectrum.

Unmasking PICADAR's Blind Spots: The Evidence for Limited Sensitivity

FAQs: Core Performance and Limitations of PICADAR

Recent large-scale studies indicate that the PICADAR tool has significant limitations in sensitivity. A 2025 study of 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD found that PICADAR had an overall sensitivity of only 75% when using the recommended cutoff score of ≥5 points. This means the tool would miss approximately one in four true PCD cases [1].

A critical design limitation is that the tool's algorithm begins by excluding all individuals who do not report a daily wet cough. The same 2025 study found that 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients did not have this symptom and would have been automatically ruled out by PICADAR without further assessment [1].

Q2: How does PICADAR performance vary across different PCD patient subgroups?

PICADAR demonstrates markedly different sensitivity across patient subgroups, with particularly poor performance in certain populations. The table below summarizes the key disparities identified in recent research [1]:

| Subgroup Characteristic | Sensitivity | Median PICADAR Score (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall PCD Population | 75% (202/269) | 7 (5–9) |

| Patients with laterality defects (e.g., situs inversus) | 95% | 10 (8–11) |

| Patients with situs solitus (normal organ arrangement) | 61% | 6 (4–8) |

| Patients with hallmark ultrastructural defects | 83% | Information missing |

| Patients without hallmark ultrastructural defects | 59% | Information missing |

This data reveals that PICADAR's sensitivity drops substantially in patients without laterality defects or in those with normal ciliary ultrastructure, missing nearly 40% of true PCD cases in these subgroups [1].

Q3: What is the recommended diagnostic workflow when using PICADAR in research?

The following workflow integrates PICADAR into a comprehensive diagnostic strategy while accounting for its known limitations:

Q4: What alternative or complementary screening approaches are available?

Given PICADAR's limitations, a multi-modal screening approach is recommended:

- Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement: Serves as a valuable screening tool, though certain genetic variants can show normal or elevated nNO values, limiting its use as a standalone test [2] [3].

- High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA): Can detect abnormal ciliary beat patterns even when other tests are normal, making it particularly valuable for identifying non-classic PCD presentations [4].

- Clinical Questionnaires: The American Thoracic Society clinical screening questionnaire (ATS-CSQ) represents an alternative, though it also has recognized sensitivity limitations [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Definitive PCD Diagnosis

Since PICADAR is only a screening tool, definitive PCD diagnosis requires specialized tests available at reference centers. The table below details key reagents and materials used in confirmatory investigations [6]:

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in PCD Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Nasal Epithelial Cells | Obtained via nasal brushing for ciliary functional and structural analysis. |

| Culture Media for Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) | Supports differentiation and growth of ciliated epithelial cells from biopsy samples. |

| Glutaraldehyde Fixative | Used for preparing ciliary samples for structural analysis by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). |

| Antibodies for Immunofluorescence (IF) | Target specific ciliary proteins (e.g., DNAH5, GAS8) to detect defects in protein localization. |

| DNA Sequencing Kits (PCD Gene Panel) | Used in genetic testing to identify biallelic mutations in known PCD-causing genes (≥40 genes). |

| Chemiluminescence Analyzer | Essential for measuring low Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) levels, a hallmark of PCD. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating PICADAR Performance in Research Cohorts

Methodology for Assessing PICADAR Sensitivity and Specificity

Objective: To evaluate the real-world performance of PICADAR in identifying patients with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia, particularly across genetic and phenotypic subgroups.

Study Population:

- Recruit patients with clinically suspected PCD or genetically confirmed PCD diagnosis.

- Ensure inclusion of diverse subgroups: patients with and without laterality defects, various genetic mutations, and different ultrastructural defects.

- Collect complete clinical histories for PICADAR parameter assessment [1] [5].

Data Collection:

- PICADAR Scoring: Calculate PICADAR scores for all participants based on seven clinical parameters:

- Full-term gestation (+1 point)

- Neonatal chest symptoms (+2 points)

- Neonatal intensive care unit admission (+1 point)

- Chronic rhinitis (+1 point)

- Ear symptoms (+1 point)

- Situs inversus (+2 points)

- Congenital cardiac defect (+2 points) [6]

- Reference Standard Testing: Perform definitive PCD diagnostic testing:

Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate overall sensitivity and specificity of PICADAR using a ≥5 cutoff point.

- Perform subgroup analyses stratifying by presence of laterality defects and ultrastructural abnormalities.

- Use statistical tests (e.g., chi-square) to compare sensitivity across subgroups [1].

Implementation Considerations:

- Account for potential recall bias, particularly for neonatal events in adult patients.

- Ensure blinding of personnel performing reference standard tests to PICADAR results.

- Collaborate with specialized PCD centers for access to advanced diagnostic techniques [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What defines a "high-risk phenotype" in the context of PCD and situs solitus? A high-risk phenotype for PCD, in this context, refers to a patient who has a classic clinical presentation of PCD but possesses two key features that can lead to a false-negative diagnostic result: situs solitus (the normal arrangement of thoracic and abdominal organs) and normal ciliary ultrastructure upon transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis [4] [7]. This specific combination is high-risk because it is frequently missed by standard diagnostic algorithms like PICADAR and some diagnostic guidelines, leaving the patient undiagnosed [4].

FAQ 2: Why does the PICADAR clinical score produce false negatives in this specific patient group? The PICADAR tool uses clinical features to identify patients requiring further testing for PCD. It has high sensitivity but lower specificity [4]. A core clinical feature included in some scoring systems is situs inversus (a mirror-image arrangement of organs), which is a strong indicator of PCD. Patients with situs solitus lack this major red flag. Consequently, when a patient has situs solitus and normal ultrastructure, their clinical score may fall below the threshold for positive screening, or they may not be referred for the full battery of necessary tests, leading to a false-negative result [4].

FAQ 3: What is the recommended diagnostic pathway for a suspected high-risk phenotype? The European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines recommend a multi-modal approach [4]. If clinical history is strong, do not exclude PCD based on a single normal test. The pathway should include:

- Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO): Should not be used in isolation to exclude PCD, as false negatives are known to occur [4].

- High-Speed Video Analysis (HSVA): Essential for detecting abnormal ciliary beat pattern and frequency, even when ultrastructure is normal [4].

- Genetic Testing: To identify mutations in PCD-associated genes known to cause disease with normal ultrastructure (e.g., DNAH11, GAS8, HYDIN) [4] [7]. The ERS suggests that both nNO and HSVA should be entirely normal before deciding further investigation is not warranted [4].

FAQ 4: Which genetic mutations are commonly associated with this phenotype? Mutations in several genes are linked to PCD with normal ultrastructure. Key genes include:

- DNAH11: A frequently identified mutation in patients with situs solitus and normal TEM [4] [7].

- CCDC103, DNAH9, RSPH1: Identified in patients with a strong clinical history and normal nNO or HSVA, but confirmed PCD via genetics [4].

- GAS8, HYDIN: Genes for which HSVA is particularly critical for diagnosis, as TEM is typically normal [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating a Patient with Strong Clinical History but Normal nNO and TEM

Problem: A patient exhibits a strong clinical history of PCD (e.g., neonatal respiratory distress, perennial wet cough, chronic otitis media, bronchiectasis) but has situs solitus, normal nNO levels, and normal ciliary ultrastructure on TEM. The initial diagnosis is negative for PCD.

Solution: This is a classic scenario for a false-negative diagnosis. The following actions are recommended:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review HSVA | Ensure that High-Speed Video Analysis has been performed by an experienced accredited center. An abnormal ciliary beat pattern is a key indicator of PCD, even with normal nNO and TEM [4]. |

| 2 | Initiate Genetic Testing | Proceed with next-generation sequencing (NGS) of a known PCD gene panel. Focus on genes associated with normal ultrastructure (e.g., DNAH11, GAS8, HYDIN) [4]. |

| 3 | Correlate Genotype with Phenotype | Ensure that identified genetic variants are pathogenic and compatible with the clinical and functional (HSVA) phenotype. This step is crucial to avoid false-positive genetic results [4]. |

Expected Outcome: A confirmed PCD diagnosis based on a combination of clinical history, abnormal HSVA, and/or identification of biallelic pathogenic mutations in a PCD-associated gene.

Guide 2: Validating Pathogenicity of Genetic Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS)

Problem: Genetic testing has identified biallelic variants of unknown significance (VUS) in a PCD-associated gene in a patient with situs solitus and normal TEM. It is unclear if this is a true PCD diagnosis.

Solution: Pathogenicity must be confirmed through functional and clinical correlation.

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Functional Studies | Perform immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy to assess the localization and expression of the corresponding protein and other ciliary components. Altered protein localization can support pathogenicity. |

| 2 | Clinical Correlation | Re-evaluate the HSVA and clinical phenotype. Does the ciliary beat pattern defect match what has been previously reported for mutations in this gene? [4] |

| 3 | Segregation Analysis | Test the parents and other family members for the VUS. Finding the variants in trans in an affected individual strongly supports pathogenicity. |

Expected Outcome: Confirmation that the genotype is the cause of the patient's ciliary phenotype, allowing for a definitive diagnosis.

Summarized Data Tables

Table 1: Diagnostic Test Profiles in PCD High-Risk Phenotypes

This table summarizes the expected results of standard PCD diagnostic tests in patients with situs solitus and specific genetic mutations.

| Gene / Mutation | Situs Status | nNO Level | HSVA (Beat Pattern) | Ciliary Ultrastructure (TEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAH11 [4] | Situs Solitus | Low / Normal | Abnormal | Normal |

| RSPH1 [4] | Situs Solitus | Low / Normal | Abnormal | May show subtle defects (e.g., microtubule disorganization) |

| HYDIN [4] | Situs Solitus | Low | Abnormal | Normal |

| GAS8 [4] | Situs Solitus | Low / Normal | Abnormal | Normal |

| CCDC103 [4] | Situs Solitus | Low / Normal | Abnormal | Normal |

| DNAH9 [4] | Situs Solitus | Low / Normal | Abnormal | Normal |

Table 2: Key Genetic Mutations and Associated Cardiac/Renal Anomalies in Situs Solitus

This table links specific genes to the risk of concurrent congenital heart defects (CHD) and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), which can be part of a broader ciliopathy phenotype.

| Gene | Chromosome | Proposed Impact / Function | Associated Anomalies (Beyond PCD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP2 [8] | 20p12.3 | Bone morphogenetic protein signaling; crucial for cardiac and skeletal development. | Isolated dextrocardia with situs solitus, short stature, skeletal anomalies. |

| ZFPM2 [9] | 8q23.1 | Ventricular septum morphogenesis. | Cardiac malformations (e.g., TOF, TGA). |

| FOXF1 [9] | 16q24.1 | Endocardial cushion development; regulation of Smoothened signaling. | VACTERL association, cardiac and renal defects. |

| ZIC3 [9] | Xq26.3 | Determination of left/right asymmetry. | Heterotaxy, VACTERL association, CHD. |

| NODAL [9] | 10q22.1 | Determination of left/right asymmetry. | Laterality defects, CHD. |

| GATA4 [9] | 8p23.1 | Cardiac morphogenesis. | Atrioventricular septal defects (AVSD). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Diagnostic Workflow for High-Risk PCD Phenotypes

Objective: To systematically diagnose Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in patients with a strong clinical history but situs solitus and normal or inconclusive initial test results.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. Methodology:

- Clinical Assessment & PICADAR Scoring: Calculate the patient's PICADAR score. Note that a score below the threshold does not rule out PCD in high-risk phenotypes [4].

- Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement: Perform nNO testing according to ATS/ERS standards. A low nNO is supportive, but a normal level cannot rule out PCD [4].

- Ciliary Biopsy and Culture: Obtain a nasal or bronchial brush biopsy. A portion of the sample should be analyzed immediately (for HSVA and initial TEM), and a portion should be cultured to differentiate primary from secondary ciliary dyskinesia.

- High-Speed Video Analysis (HSVA): Record ciliary beat pattern and frequency from freshly harvested ciliated cells. Analysis must be performed by an expert in an accredited center [4].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Process ciliated cells to analyze the internal 9+2 microtubule structure and dynein arms. Document any abnormalities or confirm normal ultrastructure.

- Genetic Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood. Perform whole exome sequencing or targeted NGS using a comprehensive PCD gene panel.

- Data Integration and Diagnosis: Correlate all findings. A definitive diagnosis of PCD is confirmed by either:

- An abnormal HSVA with a known pathogenic mutation, or

- An abnormal HSVA with diagnostic TEM findings, or

- In cases of normal TEM, an abnormal HSVA with biallelic pathogenic mutations in a PCD gene [4].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of VUS using Immunofluorescence (IF)

Objective: To determine the impact of a genetic VUS on ciliary protein localization.

Materials: Cultured ciliated epithelial cells from the patient, primary antibodies against the protein of interest and a ciliary marker (e.g., acetylated α-tubulin), fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies, confocal microscope. Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Ciliogenesis: Differentiate airway epithelial cells at an air-liquid interface (ALI) to produce a ciliated culture.

- Cell Fixation and Staining: Fix cells and permeabilize using standard IF protocols.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibodies, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies.

- Confocal Microscopy: Image the cilia using a confocal microscope.

- Analysis: Compare the localization and intensity of the protein of interest in patient cells versus healthy control cells. Absence or mislocalization of the protein supports the pathogenicity of the VUS.

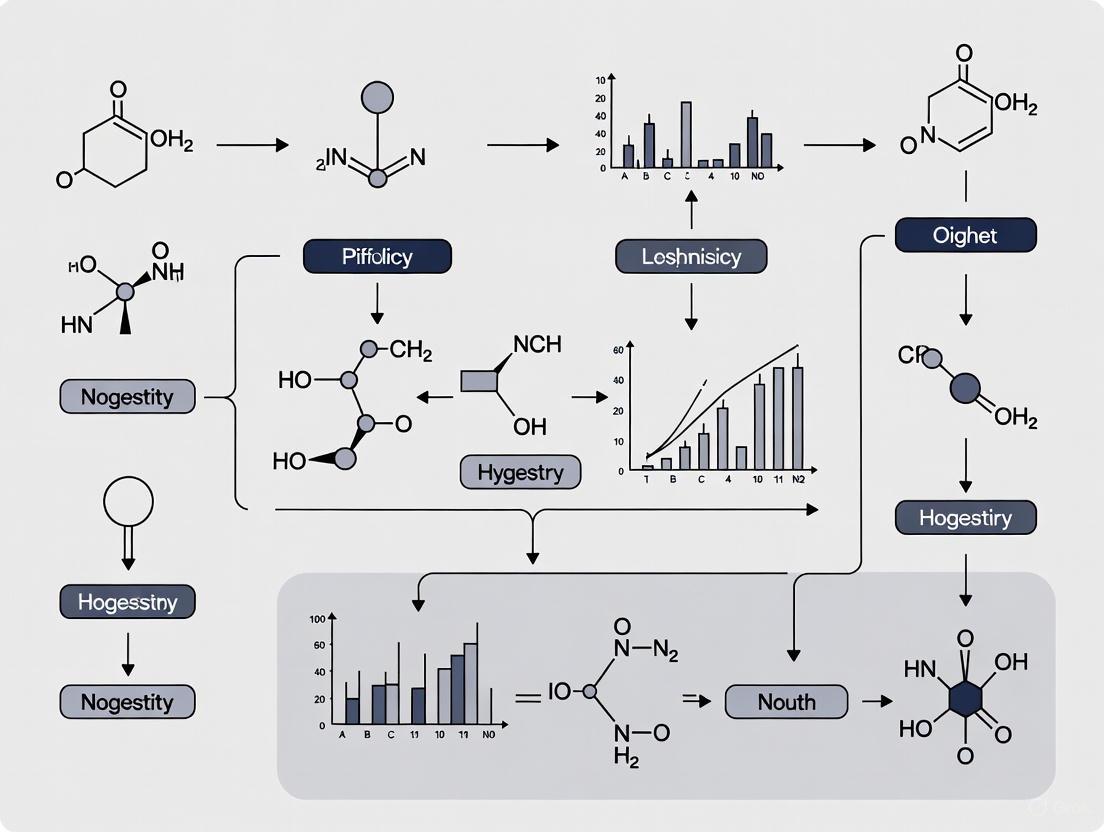

Signaling Pathways and Diagnostic Workflow

Ciliary Function and PCD Diagnostic Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application in PCD Research |

|---|---|

| Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Culture System | Differentiates primary human airway epithelial cells to generate a ciliated cell culture model for in vitro functional studies (HSVA, IF, TEM). |

| High-Speed Video Microscope | Essential equipment for capturing ciliary beat frequency and pattern at high frame rates (>500 fps) for HSVA, a critical diagnostic tool. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | Used to visualize the internal ultrastructure of cilia, including the 9+2 microtubule arrangement and outer/inner dynein arms. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Gene Panel | A targeted panel of known PCD-associated genes used to identify pathogenic mutations, especially in cases with normal TEM. |

| Anti-Acetylated α-Tubulin Antibody | A standard immunofluorescence marker that stains the ciliary axoneme, used to visualize the location and structure of cilia. |

| Anti-DNAH11 / GAS8 / etc. Antibodies | Gene-specific antibodies used in immunofluorescence to determine if a genetic mutation causes mislocalization or absence of the corresponding protein. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | A device that measures the concentration of nitric oxide in nasal air, which is typically low in most forms of PCD. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: If the daily wet cough criterion has such notable limitations, why is it so commonly used in initial screenings? The daily wet cough criterion serves as a highly specific, though poorly sensitive, initial filter. It is easily ascertainable in clinical and research settings and effectively identifies a classic PCD phenotype. However, over-reliance on this single symptom misses a significant subset of patients, as chronic wet cough is not universally present. Many individuals, particularly older children and adults, may present with a dry or intermittent cough despite having a confirmed PCD diagnosis [4].

Q2: In a research context, what specific patient populations are most at risk of being missed by this criterion? Research cohorts focusing solely on daily wet cough are likely to be biased and miss key demographic and genotypic subgroups, including:

- Patients with specific genetic variants: Individuals with mutations in genes like DNAH9 or RSPH1 often have milder respiratory symptoms and may not exhibit a daily wet cough [4].

- Older patients and adults: As individuals age, the clinical presentation can evolve, and the classic daily wet cough may become less prominent.

- Patients with effective airway clearance regimens: Subjects enrolled in rigorous physiotherapy or airway clearance studies may not report a daily wet cough, despite having the underlying ciliary defect.

Q3: What is the most robust alternative or complementary screening method for identifying research subjects? The PICADAR (PrImary CiliAry DyskinesiA Rule) tool is a validated predictive score that outperforms simple symptom checklists. It incorporates seven key clinical features to calculate a risk score, demonstrating high sensitivity (0.97) for identifying patients who require further diagnostic testing. Using a cutoff score of 4, PICADAR correctly identifies 97% of true PCD cases while maintaining reasonable specificity (0.48), ensuring research resources are allocated efficiently [4].

Q4: How do major society guidelines, like those from the ERS and ATS, differ in their approach to initial patient selection? The European Respiratory Society (ERS) and American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines offer different approaches, highlighting the lack of a single, perfect standard.

| Guideline Body | Recommended Screening Approach | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) [4] | Flexible: "patients with several typical features" or use of the PICADAR tool. | 0.97 (for PICADAR) | 0.48 (for PICADAR) |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) [4] | A four-point clinical symptoms score (possessing 2 of 4 features). | 0.80 | 0.72 |

The ATS approach, while specific, may miss up to 20% of PCD patients at the screening stage. The ERS's flexible approach and use of PICADAR aim for higher sensitivity to minimize false negatives [4].

Q5: For a research study aiming to enroll all comers with suspected PCD, what is the recommended diagnostic workflow to overcome the limitations of initial criteria? A tiered, multi-modal diagnostic protocol is essential. No single test is sufficient due to the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of PCD. The following workflow, which integrates initial screening with advanced confirmation, is recommended to minimize both false positives and false negatives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Diagnostic & Research Reagents

The following table details essential materials and assays used in advanced PCD research and diagnostics.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in PCD Investigation |

|---|---|

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVA) | Visualizes and quantifies ciliary beat frequency and pattern in real-time. Critical for detecting functional defects in patients with normal ultrastructure (e.g., DNAH11 mutations) [4]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Provides ultrastructural analysis of ciliary axonemes. Identifies hallmark defects (e.g., absent dynein arms) based on the BEAT-PCD TEM criteria (Class I/II alterations) [10]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | Genetic screening for pathogenic variants in over 50 known PCD-related genes. Essential for confirming diagnosis and correlating genotype with phenotypic data [4] [10]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | Measures nasal NO levels, which are characteristically very low in most PCD patients. Used as a rapid, non-invasive screening test, though it can yield false negatives [4]. |

| Immunofluorescence (IF) Labeling | Uses fluorescent antibodies to visualize and localize specific ciliary proteins. Helps confirm the pathogenic effect of genetic variants of uncertain significance (VUS) by showing mislocalization of proteins [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVA) Analysis

- Sample Collection: Nasal epithelial tissue is collected via cytological brushing of the inferior turbinate.

- Sample Preparation: The sample is immediately placed in culture medium and analyzed within 24 hours to maintain ciliary vitality.

- Data Acquisition: Ciliary motion is recorded using a high-speed camera (≥500 frames per second) mounted on a phase-contrast microscope.

- Analysis: Recordings are analyzed manually and/or with specialized software for ciliary beat frequency and, critically, beat pattern. Dyskinetic, stiff, or circular patterns are indicative of PCD [4].

Protocol 2: Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for BEAT-PCD Criteria

- Fixation: The ciliated biopsy is fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde for a minimum of 3 hours at 4°C.

- Processing: The sample is washed in a phosphate buffer, post-fixed in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and embedded in resin.

- Sectioning & Staining: Ultrathin sections (60-90 nm) are cut and stained with heavy metals (e.g., uranyl acetate and lead citrate).

- Imaging & Classification: A minimum of 100 ciliary cross-sections are imaged and classified according to the international BEAT-PCD TEM criteria [10]:

- Class I (Hallmark Defects): >50% of axonemes with Outer Dynein Arm (ODA) defects ± Inner Dynein Arm (IDA) defects.

- Class II (Supportive Defects): Includes central complex defects, microtubular disorganization with IDA present, or ODA defects in 25-50% of cross-sections. These require additional supportive evidence for a definitive diagnosis.

Quantitative Data on Diagnostic Tool Performance

The limitations of single-criterion screening and the relative performance of various diagnostic tools are summarized in the table below.

| Diagnostic Tool / Criterion | Utility & Strengths | Limitations & False Negative Rates |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Wet Cough Criterion | High specificity; easy to administer. | Low sensitivity; misses atypical and milder phenotypes. |

| PICADAR (Score ≥4) | High sensitivity (0.97); validated clinical score. | Moderate specificity (0.48); may refer some non-PCD patients [4]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | Excellent screening tool; high specificity in classic PCD. | False negatives occur in genes like RSPH1 and DNAH9 [4]. |

| High-Speed Video Analysis (HSVA) | Detects functional defects; identifies TEM/genetic false negatives. | Requires significant expertise; result can be subjective [4]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Gold standard for ultrastructural defects; high specificity. | ~20-30% false negative rate; normal ultrastructure in some genetic forms [4]. |

| Genetic Testing | Provides definitive diagnosis; identifies all biallelic pathogenic variants. | Inconclusive with Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS); ~10% of genes unknown [10]. |

Genetic and Ultrastructural Diversity Underlying Diagnostic Escapes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Troubleshooting Diagnostic Challenges

1. Our clinical screening using the PICADAR tool failed to identify a patient who was later genetically confirmed to have PCD. What are the known limitations of this predictive rule?

The PICADAR tool has demonstrated significant limitations in sensitivity, particularly in specific patient subgroups. Recent validation studies found its overall sensitivity to be approximately 75% in a genetically confirmed PCD cohort. Performance varies substantially based on patient characteristics [11]:

- Situs solitus (normal organ arrangement): Sensitivity drops to 61%

- Absence of hallmark ciliary ultrastructural defects: Sensitivity drops to 59%

- Lack of daily wet cough: The tool's initial question excludes these patients from further scoring, yet 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients do not report this symptom [11].

Recommended Action: Do not rely on PICADAR as the sole factor for initiating a PCD diagnostic work-up. For patients with a strong clinical history but low PICADAR scores, proceed to specialist testing [4] [11].

2. What is the recommended diagnostic pathway when genetic and ultrastructural results are discordant (e.g., pathogenic mutations found but TEM appears normal)?

Discordance between genetic and ultrastructural findings is a common diagnostic escape scenario, occurring in 20–30% of true PCD cases [4]. This is frequently associated with mutations in genes such as DNAH11 and HYDIN.

Recommended Action: Follow a multi-method diagnostic approach as per European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines. If genetic testing identifies biallelic pathogenic mutations in a PCD-associated gene, the diagnosis is confirmed even with normal TEM. Furthermore, an abnormal high-speed video analysis (HSVA) showing a dyskinetic ciliary beat pattern can indicate that PCD is "highly likely," and a PCD treatment plan should be initiated while awaiting confirmatory tests [4].

3. How can we mitigate the risk of false-positive genetic results in PCD diagnosis?

A significant pitfall in genetic testing is the misinterpretation of variants of unknown significance (VUS). It is not uncommon for individuals without PCD to have biallelic VUS in PCD-related genes, which severely reduces the specificity of genetic testing [4].

Recommended Action: Always ensure the genetic findings are compatible with the clinical and ciliary phenotype. Correlate the genotype with results from HSVA, TEM, and/or immunofluorescence labeling. A genotype is only considered confirmatory if the mutations are known to be pathogenic and match the observed phenotype [4].

Troubleshooting Guides for Key Experimental Challenges

Guide 1: Overcoming Limitations of Clinical Prediction Tools

Problem: A clinical prediction score (e.g., the 4-point ATS score or PICADAR) is being used for referral, leading to missed diagnoses.

Solution: Implement a multi-parameter and sensitive screening strategy.

Step 1: Broaden Clinical Suspicion Move beyond a rigid scoring system. Consider a flexible approach for any patient presenting with "several typical features" of PCD, such as neonatal respiratory distress at term, daily wet cough, persistent rhinitis, and unexplained bronchiectasis [4] [12].

Step 2: Utilize Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) as a Triage Tool Use nNO measurement as a sensitive, though not specific, screening test. A diagnostically low nNO value warrants further investigation, even if other screens are normal [4].

Step 3: Integrate High-Speed Video Analysis (HSVA) HSVA can detect ciliary beat pattern abnormalities in patients with normal nNO and TEM. The ERS guideline suggests that both nNO and HSVA should be entirely normal before ruling out the need for further PCD testing [4].

Table: Comparison of PCD Diagnostic Predictive Tools

| Tool Name | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR | 75% (Overall); 61% (Situs Solitus) [11] | 75% [12] | Low sensitivity in patients without laterality defects or hallmark ultrastructural defects; excludes patients without daily wet cough [11]. |

| ATS 4-Feature Score | 80% [4] | 72% [4] | May miss 20% of PCD patients; designed to select only the most likely cases for diagnostic services [4]. |

Guide 2: Validating Pathogenicity of Genetic Variants

Problem: Genetic testing has identified biallelic variants of unknown significance (VUS), and their clinical relevance is uncertain.

Solution: A functional and correlative validation workflow is essential.

Step 1: Phenotypic Correlation with HSVA If possible, obtain a ciliary biopsy and perform HSVA. A clearly abnormal, dyskinetic ciliary beat pattern supports the pathogenicity of the VUS [4] [13].

Step 2: Ultrastructural Correlation with TEM Analyze the ciliary ultrastructure. Certain genetic mutations are linked to specific TEM defects (e.g., outer dynein arm缺失), while others (e.g., DNAH11) yield normal TEM. The observed structure should be consistent with the known genotype-phenotype association [4].

Step 3: Employ Immunofluorescence (IF) Labeling Use antibodies against proteins encoded by the gene harboring the VUS. A marked reduction or absence of protein localization in the ciliary axoneme provides strong functional evidence for variant pathogenicity [4].

Step 4: Check for Compensatory Mutations Be aware that in some cases, a second-site mutation (compensatory evolution) can restore fitness without reversing the resistance phenotype, complicating genotype-phenotype maps [13].

Guide 3: Implementing a Multi-Modal Diagnostic Workflow to Capture All Cases

Problem: Reliance on a single "gold standard" test is resulting in diagnostic escapes.

Solution: Adopt a holistic diagnostic algorithm that leverages the complementary strengths of multiple techniques to account for genetic and ultrastructural diversity. The following workflow integrates the key methods for a comprehensive assessment.

Integrated Diagnostic Workflow for PCD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Diagnostic Escapes in PCD

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Video Microscope (HSVM) | To visualize and quantify ciliary beat frequency and pattern in real-time. | Detecting ciliary dyskinesia in patients with normal nNO and TEM (e.g., DNAH11 mutations) [4]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | To measure the level of nasal NO, which is characteristically low in most PCD patients. | Initial, non-invasive screening and triage of patients for further testing [4] [12]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | To visualize the internal ultrastructure of cilia (e.g., dynein arms, microtubules). | Identifying hallmark structural defects (e.g., ODA/IDA缺失) and correlating with genetic findings [4] [14]. |

| PCD Gene Panel (NGS-based) | To sequence known and candidate PCD genes for pathogenic mutations. | Genetic confirmation of disease, especially in cases with ambiguous or discordant functional results [4] [13]. |

| Ciliary Protein Antibodies | For immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy to localize specific proteins within the ciliary axoneme. | Validating the functional impact of VUS by showing loss of protein localization [4]. |

| Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Cell Culture System | To differentiate and culture human bronchial epithelial cells, regenerating ciliated epithelium. | Re-differentiating ciliated cells from biopsy samples for repeat HSVA or TEM, eliminating secondary dyskinesia [4] [12]. |

Enhanced Diagnostic Frameworks: Integrating Tools Beyond Clinical Scores

Diagnostic Algorithms & Quantitative Performance Gaps

Diagnostic Criteria and Workflow Comparison

| Feature | ERS Guideline (2017) | ATS Guideline (2018) | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Categorizes results into four diagnostic groups [15] | Binary diagnostic outcome [15] | ERS allows for diagnostic uncertainty; ATS provides definitive classification [15] |

| Final Diagnostic Categories | 1. PCD positive2. PCD highly likely3. PCD highly unlikely4. Inconclusive [15] | 1. PCD diagnosed2. PCD not diagnosed [15] | 15% of patients receive conflicting diagnoses between guidelines [15] |

| nNO Measurement | Recommended for patients >6 years (velum closure); suggested for children <6 years (tidal breathing) [16] | Used as a primary initial test [15] | Techniques and interpretation may vary, contributing to diagnostic discordance |

| Genetic Analysis | Considered a confirmatory test (PCD positive if biallelic pathogenic variants) [15] | Part of the primary diagnostic panel (>12 genes) [15] | Differences in gene panels and variant interpretation can affect outcomes |

| TEM Role | Confirmatory for hallmark defects; further testing recommended if normal ultrastructure but strong clinical history [16] | Used in the diagnostic pathway [15] | Specimen quality and expertise can impact results inconsistently |

| HSVM Role | Recommended for ciliary beat pattern analysis, preferably after cell culture [16] | Not explicitly defined in the studied algorithm [15] | ERS utilizes dynamic ciliary function assessment more centrally |

| Immunofluorescence | Not included in the original 2017 algorithm [15] | Not included in the 2018 algorithm [15] | Added in modified algorithms (e.g., PCD-UNIBE) to improve accuracy [15] |

Quantitative Concordance Data

A 2021 clinical study directly compared the ERS and ATS algorithms, revealing significant diagnostic discrepancies [15].

Table 1.2: Diagnostic Algorithm Concordance in a Clinical Cohort (n=54) [15]

| Diagnostic Outcome | Number of Patients | Percentage of Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| All Algorithms Concordant (PCD Positive or Negative) | 46 | 85% |

| PCD Diagnosed by ATS only | 5 | 9% |

| PCD Diagnosed by ERS only | 1 | 2% |

| PCD Diagnosed by ERS and PCD-UNIBE only | 1 | 2% |

| PCD Diagnosed by PCD-UNIBE only | 1 | 2% |

Statistical agreement was substantial between ERS and ATS (κ=0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.92) and between ATS and PCD-UNIBE (κ=0.73, 95% CI 0.53–0.92), and almost perfect between ERS and PCD-UNIBE (κ=0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.00) [15].

FAQs: Addressing Key Experimental Challenges

My study population includes patients with strong clinical symptoms but normal PICADAR scores. How should I proceed?

Proceed with full diagnostic testing. The PICADAR tool has limited sensitivity, particularly in specific subpopulations. A 2025 study found that 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients did not report a daily wet cough, which alone rules out PCD according to PICADAR [1]. The overall sensitivity of PICADAR was 75%, but it dropped to 61% in patients with situs solitus (normal organ placement) and to 59% in those without hallmark ultrastructural defects on TEM [1]. Relying solely on PICADAR will miss these cases.

What is the most critical step to reduce inter-laboratory variability in PCD diagnostic results?

Standardized cell culture and expert central review. The ERS guideline strongly recommends repeating High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) after air-liquid interface (ALI) culture to differentiate primary ciliary dyskinesia from secondary, acquired defects [16]. Furthermore, techniques like immunofluorescence staining and transmission electron microscopy should only be performed in experienced, specialist centres due to significant batch-to-batch variability and the profound impact of expertise on interpretation [17].

How do I resolve a conflicting diagnosis where ERS criteria classify a case as "PCD highly likely" but ATS criteria result in "PCD not diagnosed"?

This occurs in about 9% of cases [15]. Follow these steps:

- Re-review all primary data, focusing on the quality and concordance of each test.

- Incorporate immunofluorescence (IF) staining. IF can detect the absence of specific ciliary proteins, providing functional evidence for a genetic finding or clarifying a case with normal ultrastructure [17]. This was a key differentiator in the PCD-UNIBE algorithm [15].

- Consider expanded genetic testing. Next-generation sequencing panels may identify variants in genes not covered in initial tests, especially for patients with normal ultrastructure [16].

- Refer to a specialized multidisciplinary board for a final consensus diagnosis [15].

Are there any newly proposed international standards to overcome these inconsistencies?

Yes. In September 2025, the ERS and ATS published new joint international guidelines to create a unified diagnostic approach. These new guidelines strongly recommend a combination of tests—including nasal nitric oxide, genetic testing, TEM, HSVM, and immunofluorescence—emphasizing that no single test is sufficient to confirm or exclude PCD [17]. This unified guideline aims to resolve the discrepancies of the past.

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Testing

Protocol: High-Speed Videomicroscopy (HSVM) with ALI Culture

Objective: To assess ciliary beat frequency and pattern, distinguishing primary from secondary dyskinesia.

Methodology Details:

- Nasal Brushing: Obtain nasal epithelial cells using minimally invasive interdental brushes [15].

- Initial HSVM: Record ciliary motion from fresh cells immediately after brushing. Use an inverted microscope with a high-speed camera (e.g., 300 fps). Analyze ciliary beat pattern (CBP), frequency, amplitude, and coordination [15].

- ALI Culture: Culture the harvested cells at an air-liquid interface to promote ciliary differentiation and eliminate secondary inflammatory effects [15].

- Post-Culture HSVM: Repeat the HSVM analysis on the cultured cells. The persistence of an abnormal CBP after culture is indicative of PCD [16] [15].

Troubleshooting Tip: If ciliary beating is immotile or dyskinetic in fresh cells but normalizes after culture, this suggests a secondary, reversible cause rather than PCD.

Protocol: Diagnostic Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining

Objective: To detect the absence or mislocalization of ciliary proteins, confirming defects suggested by genetics or HSVM.

Methodology Details:

- Sample Preparation: Use ciliated epithelial cells, preferably from ALI culture, fixed on slides [15].

- Antibody Staining: Apply a panel of antibodies targeting key ciliary proteins. A standard panel should include DNAH5, GAS8, and RSPH9. Expand the panel based on HSVM findings or genetic results (e.g., stain for DNAH11 in cases of stiff, low-amplitude beating) [15].

- Imaging and Analysis: Use fluorescence microscopy to visualize antibody binding. Compare against healthy control samples. The absence of specific protein signals is a strong indicator of PCD [17].

Troubleshooting Tip: Include a positive control (e.g., antibody against acetylated tubulin) to confirm the presence of cilia in the sample. Batch-to-batch variability of antibodies is a known issue, so validate new batches with known positive and negative controls [17].

Diagnostic Pathway Visualization

PCD Diagnostic Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5.1: Essential Materials for PCD Diagnostic Research

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence nNO Analyzer | Measures nasal nitric oxide flow; a key screening tool. | Use velum closure technique for patients >6 years; tidal breathing for younger children [16] [17]. |

| High-Speed CMOS Camera (>200 fps) | Records ciliary motion for HSVM analysis. | Essential for detailed assessment of ciliary beat pattern, not just frequency [16] [15]. |

| Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Culture System | Differentiates primary from secondary ciliary dyskinesia. | Culturing cells is superior to analysis of fresh cells alone [16] [15]. |

| Antibody Panel for IF | Detects absence/mislocalization of ciliary proteins. | Standard panel: DNAH5, GAS8, RSPH9. Expand based on phenotype (e.g., DNAH11, RSPH1) [15]. Validate batches [17]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | Visualizes ultrastructural defects in ciliary axoneme. | Follows BEAT-PCD TEM criteria for standardized reporting [15]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Panel | Identifies pathogenic variants in >50 known PCD genes. | Crucial for confirming diagnosis, especially in cases with normal TEM [16] [17]. |

The Role of High-Speed Video Microscopy in Detecting Atypical Cases

FAQs: High-Speed Video Microscopy in PCD Diagnostics

Q1: How does High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) address the limitations of PICADAR and other clinical prediction scores in research?

Clinical prediction scores like PICADAR are used to identify patients who should undergo definitive testing for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD). While PICADAR has a high sensitivity (approximately 0.97), its specificity is lower (approximately 0.48), meaning it correctly identifies most true cases but also flags many individuals who do not have PCD [4]. In a research context focused on overcoming false negatives, HSVA is crucial because it can detect PCD cases with normal ultrastructure (false negatives from Transmission Electron Microscopy) and atypical beat patterns that may be missed by screening algorithms alone [4] [18]. It serves as a functional first-line test to capture these atypical cases.

Q2: What are the key PCD genotypes that HSVA can detect which might be missed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM)?

A significant number of PCD cases (approximately 20-30%) have normal ciliary ultrastructure when examined by TEM [4] [19]. HSVA is particularly valuable for identifying these atypical cases. Key genotypes include:

- DNAH11: Patients typically have a hyperkinetic and irregular ciliary beat pattern [20] [18].

- HYDIN, CCDC164, DNAH9, and GAS8: These genotypes can also present with PCD despite normal TEM findings, and their ciliary function is best assessed via HSVA [21] [18].

- RSPH1 and RSPH4A: These mutations can lead to unexpected beat patterns that may be non-diagnostic without functional analysis [21].

Q3: What are the primary causes of false-positive and false-negative results in HSVA, and how can they be mitigated in a research protocol?

False positives often result from secondary dyskinesias caused by factors like infection, smoking, or sample processing damage, which can alter the ciliary beat pattern [18]. False negatives can occur because defects in at least six known PCD-associated genes (e.g., HYDIN, CCDC164) can result in normal or non-diagnostic HSVA results [21]. Mitigation strategies:

- Cell Culture: The European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines strongly recommend regrowing ciliary samples at the air-liquid interface to eliminate secondary dyskinesias, though this is a weeks-long process [21].

- Repeat Testing: Diagnosis should be confirmed by repeating HSVA at least twice at different times and showing identical aberrations [18].

- Multi-Modal Diagnosis: HSVA should not be used alone. Findings should be corroborated with other methods like genetic testing, immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM), or nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement [4] [21] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides for HSVA Experiments

Guide 1: Addressing Non-Diagnostic or Inconclusive Video Footage

Problem: Recorded video clips show insufficient ciliary movement, excessive mucus, or contamination with blood cells. Solutions:

- Cause A: Poor Sample Quality. Ensure the patient has been on a two-week course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (terminated 2 days before the procedure) to eradicate biofilms that interfere with cilia function [20].

- Cause B: Epithelial Injury. Nasal brushing should be quick (approximately 2 seconds) to avoid severe epithelial injury and consequent epistaxis, which leads to contamination with red blood cells [20].

- Cause C: Mucus Overlay. Ask the patient to blow their nose thoroughly before brushing to diminish the overlay of mucous material on the epithelial cell strips [20].

Guide 2: Managing Discrepancies Between HSVA and Genetic Results

Problem: A research subject has a strong clinical phenotype and low nNO, but HSVA results are normal, and genetic testing reveals variants of unknown significance (VUS). Solutions:

- Action 1: Correlate Genotype with Phenotype. It is essential to ensure that the genotype is compatible with the ciliary phenotype using HSVA, TEM, and/or immunofluorescence labeling [4]. Not all biallelic VUS are pathogenic.

- Action 2: Utilize IFM. Immunofluorescence microscopy can reveal proteins that are absent from the cilia's axial filament, providing functional evidence to support or refute the genetic findings [19].

- Action 3: Consider Extended Analysis. Remember that normal HSVA does not exclude PCD. Proceed to further testing, including TEM and extended genetic panels, as the specificity of genetic testing is reduced when variants are of unknown significance [4] [21].

Quantitative Data on PCD Diagnostic Modalities

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Key PCD Diagnostic Tools

| Diagnostic Method | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Video Analysis (HSVA) | 100% (in expert hands) [20] | 96% (in expert hands) [20] | Non-standardized; requires expertise; false negatives possible for specific genotypes [21] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | ~70% [19] [18] | High (when abnormal) | Misses ~30% of PCD cases with normal ultrastructure [20] [19] |

| Genetic Testing | ~70-80% [19] | High (for known pathogenic variants) | Up to 30% of cases have negative or ambiguous results; variants of unknown significance are common [4] [19] |

| Clinical Score (PICADAR) | 0.97 [4] | 0.48 [4] | A screening tool, not a diagnostic; needs validation in primary care [4] |

Experimental Protocol: HSVA for Atypical PCD Case Identification

This protocol is designed for research settings focused on validating PCD diagnoses where first-line tests are inconclusive.

Step 1: Patient Identification and Sample Collection

- Identify Subjects: Use a flexible clinical approach or the PICADAR tool (cutoff ≥4 points) to select patients with a high pre-test probability of PCD for research inclusion [4].

- Brush Biopsy: Using a 0.6 mm interdental brush, brush the inferior turbinate of both nostrils for approximately 2 seconds to collect epithelial cell strips [20].

- Sample Preservation: Immediately place the harvested cell strips into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) [20].

Step 2: Sample Transport and Preparation

- Transport: Fix the tube in a polystyrene box with a cold pack (4-8°C). Do not freeze the specimen. Analysis must be performed within 24 hours [20].

- Preparation for Imaging: Warm the sample to 37°C to mimic in vivo conditions. Pipette two drops into a glass-bottom dish or cuvette for microscopy [20].

Step 3: High-Speed Video Recording

- Microscopy Setup: Use a differential-interference microscope with an oil immersion lens (100x magnification) and a high-speed video camera capable of recording at least 200 frames per second [20].

- Recording: Search for cell clusters with low mucus and no red blood cells. Record video sequences of cilia from the side and top views. Record multiple representative regions of interest [20].

Step 4: Video Analysis for Ciliary Beat Frequency (CBF) and Pattern (CBP)

- CBF Analysis: Play videos back frame-by-frame. Count 10 consecutive beats and record the number of frames elapsed. Calculate CBF using the formula: CBF (Hz) = (10 * Frame Rate) / X, where X is the number of frames for 10 beats [20]. Compare to age-specific reference values.

- CBP Analysis: Two independent, experienced operators should qualitatively assess the waveform for abnormalities such as dyskinesia, circular movement, or reduced amplitude [20] [18]. The diagnosis of PCD is "highly likely" with a repeatedly dyskinetic beat pattern, even if genetics and TEM are normal [4].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key experimental and decision-making steps for using HSVA in a research setting focused on atypical PCD cases.

Research Reagent Solutions for HSVA

Table 2: Essential Materials for HSVA Experiments

| Item | Function / Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Interdental Brush (0.6 mm) | Harvesting respiratory epithelial cells from the inferior turbinate via brushing [20]. |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Cell-nourishing medium for sample preservation during storage and transport; maintains cell viability [20]. |

| Glass-Bottom Dish or Cuvette | Holds the sample during microscopy, providing an optimal surface for high-resolution imaging [20]. |

| Differential-Interference Microscope | Provides high-contrast images of unstained, living ciliated cells by enhancing interference patterns [20]. |

| High-Speed Video Camera (≥200 fps) | Captures the rapid motion of cilia, allowing for detailed frame-by-frame analysis of beat pattern and frequency [20]. |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) | Administered prior to brushing to eradicate biofilms that can interfere with and obscure true cilia function [20]. |

Genetic Panel Testing and Whole Genome Sequencing as First-Line Tools

Diagnostic Performance & Quantitative Data

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of traditional predictive tools versus modern genetic sequencing techniques in diagnosing Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PCD Diagnostic Tools

| Diagnostic Tool | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Limitations / Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR (Clinical Score) | 75% (Overall); 61% (Situs Solitus); 59% (Normal Ultrastructure) [11] | 75% (for cutoff score of 5) [12] | Low sensitivity in patients without laterality defects or hallmark TEM findings [11]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | Varies; less specific in young children (AUC 0.75) [22] | Varies; improves with genetic testing (AUC 0.97) [22] | Requires patient cooperation; results are non-specific and must be combined with other tests [4] [22]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | ~70-80% (20-30% false-negative rate) [4] [23] | High for hallmark defects | Normal ultrastructure does not rule out PCD; identifies ~70% of cases [4] [5] [23]. |

| Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | 94% diagnostic yield in highly suspicious cohort [22] | High when biallelic pathogenic variants are identified | Can establish alternative diagnoses; accuracy improves with trio-based testing [22] [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Our research cohort is screened with PICADAR, but we suspect we are missing genetically confirmed PCD cases. What is the primary pitfall?

Challenge: The PICADAR tool has a critical design limitation for research populations. Its initial question regarding "daily wet cough" automatically rules out PCD in individuals without this symptom. A recent study found that 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients did not report a daily wet cough and would have been excluded from further testing by PICADAR alone [11]. Furthermore, its sensitivity plummets to ~60% in patients with normal organ arrangement (situs solitus) or those without hallmark ultrastructural defects on TEM [11].

Solution: Do not use PICADAR as a standalone enrollment criterion for research. It should be supplemented with other clinical features like unexplained neonatal respiratory distress in term infants, persistent rhinitis, or a history of recurrent otitis media. For definitive cohort building, proceed directly to genetic testing in cases with strong clinical suspicion, even if the PICADAR score is low [4] [11].

FAQ 2: When designing a genetic study for PCD, what are the key practical considerations for choosing between Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)?

Challenge: Choosing the most efficient and cost-effective genetic testing strategy.

Solution: The choice depends on the research objectives, budget, and existing genetic knowledge of the cohort.

Table 2: WES vs. WGS at a Glance

| Feature | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Protein-coding exons (~1-2% of genome) [24] | Entire genome, including non-coding regions [24] |

| Data Volume | ~10 GB per sample [24] | ~120 GB per sample (12x larger) [24] |

| Variant Load | ~50,000 variants per sample [24] | ~3 million variants per sample (60x more) [24] |

| Best For | Identifying pathogenic variants in known coding regions [22] | Discovering novel non-coding variants, structural variants (SVs), and copy number variants (CNVs) [24] |

| Cost & Analysis | Lower cost; faster analysis (e.g., ~2 hours) [24] | Higher cost (2-5x WES); computationally intensive (e.g., ~24 hours analysis) [24] |

| Key Limitation | May miss non-coding and structural variants [24] | Many variants in non-coding regions are of unknown significance; interpretation is challenging [24] |

For most diagnostic-oriented research, WES is an excellent first-line tool due to its high diagnostic yield (94%) and lower cost [22]. WGS is recommended when research aims to discover novel non-coding variants or structural defects, or when a patient has a strong clinical phenotype but previous genetic tests are negative [24].

FAQ 3: A significant number of genetic variants from our NGS data are classified as "Variants of Uncertain Significance" (VUS). How can we mitigate this in our analysis?

Challenge: Interpreting VUS, especially in non-coding regions identified by WGS, is a major hurdle [24].

Solution:

- Utilize Trio-Based Sequencing: Sequencing the proband and both parents allows for precise determination of de novo mutations and inheritance patterns, dramatically improving the identification of pathogenic variants [24].

- Implement Ensemble Genotyping: Using multiple variant-calling algorithms on the same dataset and integrating the results can reduce false positives by over 98% while retaining >95% of true positives, leading to more reliable variant sets for interpretation [25].

- Correlate with Functional Phenotypes: Whenever possible, correlate genetic findings with ciliary phenotype data from High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) or TEM. A VUS in a PCD gene combined with an abnormal ciliary beat pattern strongly supports pathogenicity [4].

- Incorporate Transcriptome Analysis (RNA-seq): Using RNA sequencing in parallel can confirm the functional impact of a variant on splicing or gene expression, which was essential for diagnosis in 18% of cases in one study [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Untargeted Whole-Exome Sequencing for PCD Diagnosis

This protocol is adapted from a prospective clinical study that demonstrated a 94% diagnostic yield [22].

1. Patient Selection & Sample Preparation:

- Cohort: Include patients with a high clinical suspicion of PCD. Key criteria include: term-born with chronic sinopulmonary symptoms since early childhood, plus one or more of: unexplained bronchiectasis, situs inversus/heterotaxy, or history of unexplained neonatal respiratory distress [22].

- Controls: Include family members (trio-based design is ideal) for segregation analysis [24].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from whole blood using standard kits (e.g., FlexiGene DNA Kit) [5].

2. Exome Sequencing & Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Library Preparation: Use an exome enrichment kit (e.g., SureSelect Human All Exon kit) [22].

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on a platform such as an Illumina HiSeq2500 to generate high-quality 125-bp paired-end reads [22].

- Alignment & Variant Calling: Align reads to the human reference genome (e.g., GRCh37/hg19) using a standard aligner (e.g., BWA). Call variants using a pipeline like GATK. Ensure minimum coverage of 50x across the exome [22].

- Variant Filtering & Prioritization:

- Focus on non-synonymous, splice-site, and loss-of-function (stop-gain, frameshift) variants.

- Filter against population frequency databases (e.g., gnomAD) to remove common polymorphisms.

- Prioritize rare (e.g., MAF <0.1%) biallelic variants in known PCD-related genes. A list of over 50 causative genes is available in current reviews [23].

3. Validation & Interpretation:

- Confirmation: Confirm putative pathogenic variants using an orthogonal method like Sanger sequencing [25].

- Segregation Analysis: Check that biallelic variants are in trans (on different parental alleles).

- Pathogenicity Assessment: Classify variants according to ACMG/AMP guidelines. Correlate the genotype with the clinical phenotype and any available functional ciliary data (e.g., HSVA, TEM) [4] [5].

Protocol 2: A Multipronged Approach to Overcome PICADAR False Negatives

This workflow integrates multiple diagnostic tools to comprehensively identify PCD cases that would be missed by clinical prediction rules alone [4] [22] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for PCD Genetic Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | High-quality genomic DNA extraction from whole blood or cells. | FlexiGene DNA Kit (Qiagen) [5] |

| Exome Enrichment Kit | Captures and enriches exonic regions from genomic DNA for sequencing. | SureSelect Human All Exon Kit (Agilent) [22] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Service | Provides comprehensive sequencing of the entire genome. | Services from Illumina, Complete Genomics [25] |

| Variant Annotation Database | Annotates identified variants with population frequency and functional impact. | dbSNP, snpEff with Ensembl transcript model [25] |

| PCD Gene Panel | A curated list of genes known to cause PCD for targeted analysis. | Over 50 genes (e.g., DNAH11, DNAH5, CCDC39, CCDC40) [23] |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | For alignment, variant calling, and filtering of NGS data. | BWA for alignment, GATK for variant calling [22] |

Immunofluorescence and TEM in the Era of Genomic Medicine

In the diagnosis of complex genetic disorders like Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), genomic medicine has provided powerful tools such as PICADAR (Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Aided Diagnosis), a validated clinical tool that uses symptoms and clinical history to calculate a probability for PCD. However, even the most sophisticated genetic screening can yield false negatives due to novel pathogenic variants, genes not included in testing panels, or complex genetic interactions that escape detection.

This technical support center establishes how the integrated application of immunofluorescence (IF) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) can overcome these diagnostic limitations. When PICADAR suggests a high probability of PCD yet genetic tests are inconclusive, these morphological and ultrastructural techniques provide a critical pathway to a definitive diagnosis. The following guides and protocols are designed to help researchers and clinicians validate findings, troubleshoot diagnostic challenges, and characterize novel disease mechanisms at the subcellular level.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses specific experimental challenges encountered when correlating immunofluorescence and TEM data, particularly in the context of PCD diagnosis and research.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Inconclusive TEM results despite strong clinical suspicion of PCD.

- Potential Cause: Secondary ciliary dyskinesia due to infection or inflammation, which can cause transient ultrastructural defects that mimic PCD.

- Solution:

- Repeat Biopsy: Collect a new nasal brush or biopsy after the patient has recovered from acute respiratory infection.

- Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Culture: Culture the ciliated epithelium to allow regeneration of cilia in a controlled, infection-free environment. Repeat TEM on the cultured cells [26] [27].

- Correlative IF: Perform immunofluorescence testing on the same sample. The absence of a specific ciliary protein (e.g., DNAH5) by IF confirms a true primary defect, whereas secondary defects typically show normal protein presence [26].

Problem: Poor or absent immunofluorescence signal in samples with good morphology.

- Potential Cause: Antigen masking or destruction due to over-fixation, especially with high concentrations of glutaraldehyde.

- Solution:

- Optimize Fixation: Use a combination of low concentrations of paraformaldehyde (e.g., 2-4%) and glutaraldehyde (e.g., 0.1-0.5%) to balance morphology and antigen preservation [28].

- Use Tokuyasu Cryosectioning: For TEM correlation, prepare samples using the Tokuyasu method (slight fixation, sucrose infusion, cryosectioning). This method is renowned for superior preservation of antigenicity [29] [28].

- Anticide Selection: Validate antibodies specifically for use on TEM samples or cryosections. Not all antibodies suitable for light microscopy work well for EM-level immunolabeling [28].

Problem: Discrepancy between IF and genetic results.

- Potential Cause: Mislocalization, rather than absence, of a ciliary protein. Some genetic mutations allow protein synthesis but disrupt its transport and incorporation into the ciliary axoneme.

- Solution:

- High-Resolution IF: Use super-resolution or confocal microscopy to precisely localize the protein within the cell. Look for accumulation in the cell body instead of the cilia.

- TEM Correlation: Use TEM to identify the specific ultrastructural defect (e.g., missing dynein arms). Correlate this Class 1 defect with the IF pattern to build a conclusive diagnostic case [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What constitutes a definitive PCD diagnosis by TEM, and how does it relate to IF findings?

A: According to the international BEAT PCD TEM consensus guideline, a definitive diagnosis can be made by identifying "Class 1" defects [27]. These hallmark defects are highly specific for PCD and include:

- Outer Dynein Arm (ODA) Defect: Absence from the majority of doublets in >50% of axonemes.

- Combined ODA and Inner Dynein Arm (IDA) Defect: Absence of both structures.

- Microtubular Disorganization with IDA Defect: Disordered microtubule arrangement coupled with missing IDAs.

IF findings directly complement these observations. For example, the absence of DNAH5 (an ODA protein) by IF correlates with ODA defects on TEM, providing molecular validation for the ultrastructural observation [26] [27].

Q2: Our research aims to discover novel PCD genes. How can IF/TEM guide genetic analysis?

A: IF and TEM are powerful for phenotyping patients with inconclusive genetic results. The workflow is as follows:

- Phenotype First: Use TEM to categorize the patient's defect (e.g., ODA defect, IDA defect, central pair apparatus defect).

- Molecular Phenotyping: Use a targeted IF antibody panel (e.g., against DNAH5 for ODAs, DNALI1 for IDAs, RSPH4A for radial spokes) to pinpoint the missing protein complex [26].

- Prioritize Genetic Analysis: This phenotypic data allows you to prioritize sequencing of genes known to be associated with that specific defect, or to focus the search for novel genes within pathways governing that particular ciliary complex.

Q3: What is the recommended sample preparation workflow for combined IF and TEM analysis?

A: The optimal workflow that preserves both antigenicity for IF and ultrastructure for TEM involves the following key steps [29] [28]:

Q4: What are the specific advantages of using the Tokuyasu method for immuno-TEM?

A: The Tokuyasu cryosectioning method offers several distinct advantages for correlative microscopy [29] [28]:

- Superior Antigen Preservation: Because embedding in plastic resin is avoided, more antigenic sites remain accessible to antibodies.

- Versatility: The same cryosection can be used for initial IF screening and subsequent high-resolution TEM imaging, ensuring perfect correlation.

- Robust Multiple Labeling: It facilitates reliable double- or triple-labeling experiments with different-sized gold particles, allowing for the study of multiple proteins simultaneously.

Experimental Protocols & Diagnostic Criteria

Detailed Protocol: Immunofluorescence for PCD Diagnosis

This protocol is adapted from studies validating IF as a diagnostic tool for PCD [26].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect ciliated epithelial cells via nasal brushing.

- Cytospin onto glass slides and air dry.

2. Fixation:

- Fix cells in ice-cold methanol for 10 minutes at -20°C.

- Alternatively, use 4% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes.

3. Immunostaining:

- Block with 3% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes.

- Incubate with primary antibody cocktail (e.g., anti-acetylated tubulin and anti-DNAH5) in a humidified chamber for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Wash 3x with PBS.

- Incubate with appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 568) for 45 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Wash 3x with PBS.

- Mount with antifade mounting medium containing DAPI.

4. Imaging and Analysis:

- Image using a fluorescence or confocal microscope with a 63x or 100x oil immersion objective.

- Score a minimum of 10 well-ciliated cells. The protein of interest (e.g., DNAH5) is considered "absent" if there is a consistent lack of colocalization with the ciliary marker (acetylated tubulin) along the axoneme in >70% of evaluated cilia.

Diagnostic Criteria: Interpreting TEM Results

The following table summarizes the key ultrastructural defects as defined by the international BEAT PCD TEM consensus guideline [27].

Table 1: TEM Diagnostic Criteria for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD)

| Defect Class | Ultrastructural Finding | Diagnostic Implication | Common Associated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Diagnostic) | Outer Dynein Arm (ODA) defect | Definitive for PCD | DNAH5, DNAI1, CCDC114 |

| ODA + Inner Dynein Arm (IDA) defect | Definitive for PCD | DNAAF1, DNAAF3, CCDC103 | |

| Microtubular disorganization with IDA defect | Definitive for PCD | CCDC39, CCDC40 | |

| Class 2 (Supportive) | Central apparatus defect (e.g., missing central pair) | Highly indicative of PCD, requires supporting evidence | RSPH4A, RSPH9 |

| Isolated IDA defect | Highly indicative of PCD, requires supporting evidence | Genes not well defined | |

| Mislocalization of basal bodies | Highly indicative of PCD, requires supporting evidence | CCNO | |

| Non-Diagnostic | Secondary defects (e.g., compound cilia, disorientation) | Not diagnostic for PCD; caused by infection/inflammation | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful integration of IF and TEM relies on a carefully selected toolkit of reagents and materials. The table below details essential items for experiments focused on ciliary structure and function.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Immunofluorescence and TEM Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-DNAH5 Antibody | IF marker for outer dynein arms; absence indicates ODA defects [26]. | Validated for use on cryosections and nasal brushings. |

| Anti-Acetylated Tubulin Antibody | IF marker for the ciliary axoneme; used as a reference for cilia structure and to normalize other signals [26]. | Stains the stable microtubules of the ciliary shaft. |

| Anti-RSPH4A Antibody | IF marker for the radial spoke head complex; absence indicates central apparatus defects [26]. | Useful for diagnosing a specific subclass of PCD. |

| Protein A-Conjugated Colloidal Gold | Post-embedding immunogold labeling for TEM; allows localization of specific proteins at ultrastructural resolution [28]. | Available in different sizes (e.g., 5nm, 10nm, 15nm) for multiple labeling. |

| Tokuyasu Cryosectioning Setup | Sample preparation methodology that optimally preserves both antigenicity for IF and ultrastructure for TEM [29] [28]. | Requires ultramicrotome with cryo-attachment, sucrose for infiltration. |

| Glutaraldehyde (EM Grade) | Cross-linking fixative that provides excellent preservation of ultrastructural details for TEM. | Typically used at low concentrations (0.1-0.5%) in combination with PFA for immuno-EM. |

| Uranyl Acetate & Lead Citrate | Heavy metal stains for TEM; provide contrast to cellular structures by binding to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids [27]. | Standard post-staining reagents for visualizing ciliary components. |

Integrated Diagnostic Workflow: From PICADAR to Confirmation

The following diagram illustrates the complete diagnostic and research pathway, integrating clinical assessment, genomics, and morphological techniques to conclusively overcome PICADAR false negatives.

This workflow demonstrates that when genetic testing is inconclusive, IF and TEM provide a powerful, complementary pathway not only to a definitive diagnosis but also to the discovery of new disease mechanisms and genes. By systematically applying these techniques, researchers and clinicians can effectively overcome the limitations of genetic screening alone.

Strategies for Diagnostic Improvement in Clinical and Research Settings

Developing Phenotype-Expanded Predictive Models

Understanding the Diagnostic Challenge: The Limitations of PICADAR

What is the primary weakness of the PICADAR score, and why is research into expanded models needed?

The Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule (PICADAR) is a diagnostic predictive tool recommended by the European Respiratory Society to assess the likelihood of a Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) diagnosis. However, a 2025 study has demonstrated that it has limited sensitivity, failing to identify a significant number of true PCD cases [11].

The core limitation is its reliance on specific clinical features. The tool's initial question rules out PCD in all individuals without a daily wet cough [11]. In the study, this single criterion excluded 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients from further diagnostic work-up. The overall sensitivity of the score was 75%, meaning one in four confirmed PCD patients was not identified by the tool [11].

The performance is particularly poor in key patient subgroups, as shown in the table below [11].

Table 1: PICADAR Sensitivity in Key Patient Subgroups

| Patient Subgroup | Sensitivity | Median PICADAR Score |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 75% | 7 |

| With Laterality Defects | 95% | 10 |

| With Situs Solitus (normal arrangement) | 61% | 6 |

| With Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 83% | - |

| Without Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 59% | - |

This evidence confirms that PICADAR should not be the sole factor used to initiate a PCD diagnostic work-up. Research into phenotype-expanded models is crucial to capture the full spectrum of the disease, especially for patients with normal body composition and normal ciliary ultrastructure [11].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for Predictive Model Development

FAQ: Our model is performing well on one cohort but fails to generalize to others. What strategies can improve stability?

A common challenge in multi-omics predictive modeling is a lack of generalizability across different study cohorts. This often stems from cohort-specific technical variations or biological differences not captured by the model.

- Solution: Implement Cohort-Wise Cross-Validation. Instead of a simple random split of your dataset, design your validation strategy to test the model on each independent cohort separately. This provides a more realistic estimate of how your model will perform on entirely new data from a different source [30].

- Solution: Utilize Multi-Omics Integration. For complex regression tasks like predicting biomarker levels, using multi-omics data (e.g., combining transcriptomics and methylomics) can improve performance, stability, and generalizability compared to models based on a single type of data. Visible neural networks that elegantly combine these data types at the gene level have shown promise in this area [30].

- Solution: Employ Interpretable ("Visible") Neural Networks. Using neural networks that incorporate prior biological knowledge (e.g., gene and pathway annotations) not only makes the model's decisions interpretable but can also enhance its ability to learn robust, biologically-grounded patterns that generalize better to new data [30].

FAQ: We suspect our model's interpretations are unreliable and change with each training run. How can we ensure consistency?

The reliability of model interpretations is critical for generating biological insights. Instability can indicate issues with model configuration or training.

- Troubleshooting Step: Assess Interpretation Robustness. Recent research has found that interpretations from complex models can be strongly affected by different random weight initializations. To diagnose this, you should train your model multiple times with different random seeds and then quantify the consistency of the resulting interpretations (e.g., the top important genes or features) [30].

- Best Practice: Leverage Biological Knowledge. To guard against spurious interpretations, use biologically informed neural network architectures. For instance, in a multi-omics context, you can structure your network so that individual DNA methylation sites and gene expression data are connected through a shared gene layer based on genomic annotations. This built-in structure guides the model toward biologically plausible relationships [30].

- Best Practice: Perform Cohort-Wise Consistency Checks. In a multi-cohort setting, check if the same genes and pathways are consistently identified as important across the different independent cohorts. This cross-validation of interpretations strengthens the credibility of the findings [30].

FAQ: Our bioinformatics pipeline for data preprocessing keeps failing or producing errors. What are the common issues and fixes?

Errors in bioinformatics pipelines can derail research progress. Common failure points include data quality, tool compatibility, and computational resources [31].

- Common Challenge: Data Quality Issues. Low-quality raw data (e.g., from sequencing platforms) can lead to erroneous results downstream.

- Actionable Fix: Use quality control tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to identify and remove contaminants or low-quality reads before proceeding with alignment and analysis [31].

- Common Challenge: Tool Compatibility. Conflicts between software versions or missing dependencies can disrupt the entire workflow.

- Actionable Fix: Use a workflow management system like Nextflow or Snakemake to manage software environments. Regularly update tools and use version control systems like Git to ensure reproducibility [31].

- Common Challenge: Computational Bottlenecks. Insufficient memory or processing power can cause pipelines to slow down or crash, especially with large datasets.

- Actionable Fix: Optimize parameters for tools like aligners or variant callers. For large-scale analyses, consider migrating the pipeline to a cloud computing platform (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud) that offers scalable resources [31].

Experimental Protocols for Model Development and Validation

Protocol: Building a Biologically Interpretable Multi-Omics Neural Network